13.5: Early Jewish and Christian Art

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 263999

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Early Jewish Art

Early Jewish art forms included frescoes, illuminated manuscripts and elaborate floor mosaics.

Learning Objectives

Discuss how the prohibition of graven images influenced the production of Jewish art

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Jews, like other early religious communities, were wary of art being used for idolatrous purposes. Over time, official interpretations of the Second Commandment began to disassociate religious art with graven images .

- The zodiac, generally associated with paganism , was the subject of multiple early Jewish mosaics .

- An ancient synagogue in Gaza provides a rare example of the use of graven images in mosaics, depicting King David as Orpheus.

- Dura-Europos is the site of an early synagogue, dating from 244 CE.

Key Terms

- Haggadah: A text that sets forth the order of the Passover seder.

- syncretic: Describing imagery or other creative expression that blends two or more religions or cultures.

- Tanakh: The body of Jewish scripture comprising the Torah, the Neviim (prophets), and the Ketuvim (writings), which correspond roughly to the Christian Old Testament.

- rabbinical: Referring to rabbis, their writings, or their work.

The Second Commandment and Its Interpretations

The Second Commandment, as noted in the Old Testament, warns all followers of the Hebrew god Yahweh, “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image.” As most Rabbinical authorities interpreted this commandment as the prohibition of visual art, Jewish artists were relatively rare until they lived in assimilated European communities beginning in the late eighteenth century.

Although no single biblical passage contains a complete definition of idolatry , the subject is addressed in numerous passages, so that idolatry may be summarized as the worship of idols or images; the worship of polytheistic gods by use of idols or images; the worship of trees, rocks, animals, astronomical bodies, or another human being; and the use of idols in the worship of God.

In Judaism, God chooses to reveal his identity, not as an idol or image, but by his words, by his actions in history, and by his working in and through humankind. By the time the Talmud was written, the acceptance or rejection of idolatry was a litmus test for Jewish identity. An entire tractate, the Avodah Zarah (strange worship) details practical guidelines for interacting with surrounding peoples so as to avoid practicing or even indirectly supporting such worship.

Attitudes towards the interpretation of the Second Commandment changed through the centuries. Jewish sacred art is recorded in the Tanakh and extends throughout Jewish Antiquity and the Middle Ages . The Tabernacle and the two Temples in Jerusalem form the first known examples of Jewish art.

While first-century rabbis in Judea objected violently to the depiction of human figures and the placement of statues in temples, third-century Babylonian Jews had different views. While no figural art from first-century Roman Judea exists, the art on the Dura-Europos synagogue walls developed with no objection from the rabbis.

Illuminated Manuscripts and Mosaics

The Jewish tradition of illuminated manuscripts during Late Antiquity can be deduced from borrowings in Early Medieval Christian art. Middle Age Rabbinical and Kabbalistic literature also contain textual and graphic art, most famously the illuminated Haggadahs like the Sarajevo Haggadah , and manuscripts like the Nuremberg Mahzor. Some of these were illustrated by Jewish artists and some by Christians. Equally, some Jewish artists and craftsmen in various media worked on Christian commissions.

Byzantine synagogues also frequently featured elaborate mosaic floor tiles. The remains of a sixth-century synagogue were uncovered in Sepphoris, an important center of Jewish culture between the third and seventh centuries. The mosaic reflects an interesting fusion of Jewish and pagan beliefs.

In the center of the floor the zodiac wheel was depicted. The sun god Helios sits in the middle in his chariot, and each zodiac is matched with a Jewish month. Along the sides of the mosaic are strips that depict the binding of Isaac and other Biblical scenes.

The floor of the Beth Alpha synagogue, built during the reign of Justinian I (518–527 CE), also features elaborate nave mosaics. Each of its three panels depicts a different scene: the Holy Ark, the zodiac and the story Isaac’s sacrifice . Once again, Helios stands in the center of the zodiac. The four women in the corners of the mosaic represent the four seasons.

As interpretations of the Second Commandment liberalized, any perceived ban on figurative depiction was not taken very seriously by the Jews living in Byzantine Gaza. In 1966, remains of a synagogue were found in the region’s ancient harbor area. Its mosaic floor depicts a syncretic image of King David as Orpheus, identified by his name in Hebrew letters. Near him are lion cubs, a giraffe and a snake listening to him playing a lyre .

A further portion of the floor was divided by medallions formed by vine leaves, each of which contains an animal: a lioness suckling her cub, a giraffe, peacocks, panthers, bears, a zebra, and so on. The floor was completed between 508 and 509 CE.

Dura-Europos

Dura-Europos, a border city between the Romans and the Parthians , was the site of an early Jewish synagogue dated by an Aramaic inscription to 244 CE. It is also the site of Christian churches and mithraea, this city’s location between empires made it an optimal spot for cultural and religious diversity.

The synagogue is the best preserved of the many imperial Roman-era synagogues that have been uncovered by archaeologists. It contains a forecourt and house of assembly with frescoed walls depicting people and animals, as well as a Torah shrine in the western wall facing Jerusalem.

The synagogue paintings, the earliest continuous surviving biblical narrative cycle, are conserved at Damascus, together with the complete Roman horse armor. Because of the paintings adorning the walls, the synagogue was at first mistaken for a Greek temple. The synagogue was preserved, ironically, when it was filled with earth to strengthen the city’s fortifications against a Sassanian assault in 256 CE.

The preserved frescoes include scenes such as the Sacrifice of Isaac and other Genesis stories, Moses receiving the Tablets of the Law, Moses leading the Hebrews out of Egypt, scenes from the Book of Esther, and many others. The Hand of God motif is used to represent divine intervention or approval in several paintings. Scholars cannot agree on the subjects of some scenes, because of damage, or the lack of comparative examples; some think the paintings were used as an instructional display to educate and teach the history and laws of the religion.

Others think that this synagogue was painted in order to compete with the many other religions being practiced in Dura-Europos. The new (and considerably smaller) Christian church (Dura-Europos church) appears to have opened shortly before the surviving paintings were begun in the synagogue. The discovery of the synagogue helps to dispel narrow interpretations of Judaism’s historical prohibition of visual images.

Early Christian Art

Early Christian, or Paleochristian, art was created by Christians or under Christian patronage throughout the second and third centuries.

Learning Objectives

Describe the influence of Greco-Roman culture on the development of early Christian art

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Early Christian, or Paleochristian, art was produced by Christians or under Christian patronage from the earliest period of Christianity to between 260 and 525.

- The lack of surviving Christian art from the first century could be due to a lack of artists in the community, a lack of funds, or a small audience.

- Early Christians used the same artistic media as the surrounding pagan culture . These media included frescos , mosaics , sculptures, and illuminated manuscripts .

- Early Christians used the Late Classical style and adapted Roman motifs and gave new meanings to what had been pagan symbols. Because the religion was illegal until 313, Christian artists felt compelled to disguise their subject matter.

- House churches were private homes that were converted into Christian churches to protect the secrecy of Christianity.

The house church at Dura-Europos is the earliest house church that has been discovered.

Key Terms

- syncretism: The conveyance of more than one religion or culture, particularly in visual art.

- Catacombs: Human-made subterranean passageways used as burial locations.

- domus ecclesiae: A term that has been applied to the earliest Christian places of worship, namely churches that existed in private homes.

- sarcophagus: A stone coffin, often inscribed or decorated with sculpture.

- canonical: According to recognized or orthodox rules.

- graven image: A carved idol or representation of a god used as an object of worship.

- cubicula: Small rooms carved out of the wall of a catacomb, used as mortuary chapels, and in Roman times, for Christian worship.

Early Christianity

By the early years of Christianity (first century), Judaism had been legalized through a compromise with the Roman state over two centuries. Christians were initially identified with the Jewish religion by the Romans, but as they became more distinct, Christianity became a problem for Roman rulers.

Around the year 98, Nerva decreed that Christians did not have to pay the annual tax upon the Jews, effectively recognizing them as a distinct religion. This opened the way to the persecutions of Christians for disobedience to the emperor, as they refused to worship the state pantheon .

The oppression of Christians was only periodic until the middle of the first century. However, large-scale persecutions began in the year 64 when Nero blamed them for the Great Fire of Rome earlier that year. Early Christians continued to suffer sporadic persecutions.

Because of their refusal to honor the Roman pantheon, which many believed brought misfortune upon the community, the local pagan populations put pressure on the imperial authorities to take action against their Christians neighbors. The last and most severe persecution organized by the imperial authorities was the Diocletianic Persecution from 303 to 311.

Early Christian Art

Early Christian, or Paleochristian, art was produced by Christians or under Christian patronage from the earliest period of Christianity to, depending on the definition used, between 260 and 525. In practice, identifiably Christian art only survives from the second century onwards. After 550, Christian art is classified as Byzantine , or of some other regional type.

It is difficult to know when distinctly Christian art began. Prior to 100, Christians may have been constrained by their position as a persecuted group from producing durable works of art. Since Christianity was largely a religion of the lower classes in this period, the lack of surviving art may reflect a lack of funds for patronage or a small numbers of followers.

The Old Testament restrictions against the production of graven images (an idol or fetish carved in wood or stone) might have also constrained Christians from producing art. Christians could have made or purchased art with pagan iconography but given it Christian meanings. If this happened, “Christian” art would not be immediately recognizable as such.

Early Christians used the same artistic media as the surrounding pagan culture. These media included frescos, mosaics, sculptures, and illuminated manuscripts.

Early Christian art not only used Roman forms , it also used Roman styles. Late Classical art included a proportional portrayal of the human body and impressionistic presentation of space . The Late Classical style is seen in early Christian frescos, such as those in the Catacombs of Rome, which include most examples of the earliest Christian art.

Early Christian art is generally divided into two periods by scholars: before and after the Edict of Milan of 313, which legalized Christianity in the Roman Empire. The end of the period of Early Christian art, which is typically defined by art historians as being in the fifth through seventh centuries, is thus a good deal later than the end of the period of Early Christianity as typically defined by theologians and church historians, which is more often considered to end under Constantine, between 313 and 325.

Early Christian Painting

In a move of strategic syncretism , the Early Christians adapted Roman motifs and gave new meanings to what had been pagan symbols. Among the motifs adopted were the peacock, grapevines, and the “Good Shepherd.” Early Christians also developed their own iconography. Such symbols as the fish (ikhthus), were not borrowed from pagan iconography.

During the persecution of Christians under the Roman Empire, Christian art was necessarily and deliberately furtive and ambiguous, using imagery that was shared with pagan culture but had a special meaning for Christians. The earliest surviving Christian art comes from the late second to early fourth centuries on the walls of Christian tombs in the catacombs of Rome. From literary evidence, there might have been panel icons which have disappeared.

Depictions of Jesus

Initially, Jesus was represented indirectly by pictogram symbols such as the ichthys, the peacock, the Lamb of God, or an anchor. Later, personified symbols were used, including Daniel in the lion’s den, Orpheus charming the animals, or Jonah, whose three days in the belly of the whale prefigured the interval between the death and resurrection of Jesus. However, the depiction of Jesus was well-developed by the end of the pre-Constantinian period. He was typically shown in narrative scenes, with a preference for New Testament miracles, and few of scenes from his Passion. A variety of different types of appearance were used, including the thin, long-faced figure with long, centrally-parted hair that was later to become the norm. But in the earliest images as many show a stocky and short-haired beardless figure in a short tunic , who can only be identified by his context. In many images of miracles Jesus carries a stick or wand, which he points at the subject of the miracle rather like a modern stage magician (though the wand is significantly larger).

The image of The Good Shepherd, a beardless youth in pastoral scenes collecting sheep, was the most common of these images and was probably not understood as a portrait of the historical Jesus. These images bear some resemblance to depictions of kouroi figures in Greco-Roman art.

The almost total absence from Christian paintings during the persecution period of the cross, except in the disguised form of the anchor, is notable. The cross, symbolizing Jesus’s crucifixion, was not represented explicitly for several centuries, possibly because crucifixion was a punishment meted out to common criminals, but also because literary sources noted that it was a symbol recognized as specifically Christian, as the sign of the cross was made by Christians from the earliest days of the religion.

House Church at Dura-Europos

The house church at Dura-Europos is the oldest known house church. One of the walls within the structure was inscribed with a date that was interpreted as 231. It was preserved when it was filled with earth to strengthen the city’s fortifications against an attack by the Sassanians in 256 CE.

Despite the larger atmosphere of persecution, the artifacts found in the house church provide evidence of localized Roman tolerance for a Christian presence. This location housed frescos of biblical scenes including a figure of Jesus healing the sick.

When Christianity emerged in the Late Antique world, Christian ceremony and worship were secretive. Before Christianity was legalized in the fourth century, Christians suffered intermittent periods of persecution at the hands of the Romans. Therefore, Christian worship was purposefully kept as inconspicuous as possible. Rather than building prominent new structures for express religious use, Christians in the Late Antique world took advantage of pre-existing, private structures—houses.

The house church in general was known as the domus ecclesiae , Latin for house and assembly. Domi ecclesiae emerged in third-century Rome and are closely tied to domestic Roman architecture of this period, specifically to the peristyle house in which the rooms were arranged around a central courtyard.

These rooms were often adjoined to create a larger gathering space that could accommodate small crowds of around fifty people. Other rooms were used for different religious and ceremonial purpose, including education, the celebration of the Eucharist, the baptism of Christian converts, storage of charitable items, and private prayer and mass . The plan of the house church at Dura-Europos illustrates how house churches elsewhere were designed.

When Christianity was legalized in the fourth century, Christians were no longer forced to use pre-existing homes for their churches and meeting houses. Instead, they began to build churches of their own.

Even then, Christian churches often purposefully featured unassuming—even plain—exteriors. They tended to be much larger as the rise in the popularity of the Christian faith meant that churches needed to accommodate an increasing volume of people.

Architecture of the Early Christian Church

After their persecution ended, Christians began to build larger buildings for worship than the meeting places they had been using.

Learning Objectives

Explain what replaced the Classical temple in Early Christian architecture and why

Key Takeaways

Key Points

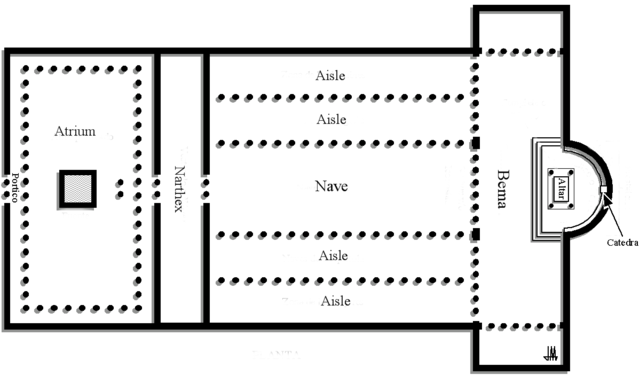

- Architectural formulas for temples were unsuitable, so the Christians used the model of the basilica , which had a central nave with one aisle at each side and an apse at one end. The transept was added to give the building a cruciform shape.

- A Christian basilica of the fourth or fifth century that stood behind an entirely enclosed forecourt that was ringed with a colonnade or arcade . This forecourt was entered from the outside through a range of buildings that ran along the public street.

- In the Eastern ( Byzantine ) Empire, churches tended to be centrally planned, with a central dome surrounded by at least one ambulatory .

- The church of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy is a prime example of an Eastern, centrally planned church.

Key Terms

- lunette: A half-moon shaped space, usually above a door or window, either filled with recessed masonry or void.

- presbytery: A section of the church reserved for the clergy.

- theophany: A manifestation of a deity to a human.

- prothesis: The place in the sanctuary in which the Liturgy of Preparation takes place in the Eastern Orthodox churches.

- fascia: A wide band of material that covers the ends of roof rafters, and sometimes supports a gutter in steep-slope roofing; typically it is a border or trim in low-slope roofing.

- basilica: A Christian church building that has a nave with a semicircular apse, side aisles, a narthex and a clerestory.

- cloister: A covered walk, especially in a monastery, with an open colonnade on one side that runs along the walls of the buildings that face a quadrangle.

- mullion: A vertical element that forms a division between the units of a window, door, or screen, or that is used decoratively.

- triforium: A shallow, arched gallery within the thickness of an inner wall, above the nave of a church or cathedral.

- diaconicon: In Eastern Orthodox churches, the name given to a chamber on the south side of the central apse of the church, where the vestments, books, and so on that are used in the Divine Services of the church are kept.

- clerestory: The upper part of a wall that contains windows that let in natural light to a building, especially in the nave, transept, and choir of a church or cathedral.

Early Christian Architecture

After their persecution ended in the fourth century, Christians began to erect buildings that were larger and more elaborate than the house churches where they used to worship. However, what emerged was an architectural style distinct from classical pagan forms .

Architectural formulas for temples were deemed unsuitable. This was not simply for their pagan associations, but because pagan cult and sacrifices occurred outdoors under the open sky in the sight of the gods. The temple, housing the cult figures and the treasury , served as a backdrop. Therefore, Christians began using the model of the basilica, which had a central nave with one aisle at each side and an apse at one end.

Old St. Peter’s and the Western Basilica

The basilica model was adopted in the construction of Old St. Peter’s church in Rome . What stands today is New St. Peter’s church, which replaced the original during the Italian Renaissance.

Whereas the original Roman basilica was rectangular with at least one apse, usually facing North, the Christian builders made several symbolic modifications. Between the nave and the apse, they added a transept, which ran perpendicular to the nave. This addition gave the building a cruciform shape to memorialize the Crucifixion.

The apse, which held the altar and the Eucharist, now faced East, in the direction of the rising sun. However, the apse of Old St. Peter’s faced West to commemorate the church’s namesake, who, according to the popular narrative, was crucified upside down.

A Christian basilica of the fourth or fifth century stood behind its entirely enclosed forecourt. It was ringed with a colonnade or arcade, like the stoa or peristyle that was its ancestor, or like the cloister that was its descendant. This forecourt was entered from outside through a range of buildings along the public street.

In basilicas of the former Western Roman Empire, the central nave is taller than the aisles and forms a row of windows called a clerestory . In the Eastern Empire (also known as the Byzantine Empire, which continued until the fifteenth century), churches were centrally planned. The Church of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy is prime example of an Eastern church.

San Vitale

The church of San Vitale is highly significant in Byzantine art, as it is the only major church from the period of the Eastern Emperor Justinian I to survive virtually intact to the present day. While much of Italy was under the rule of the Western Emperor, Ravenna came under the rule of Justinian I in 540.

The church was begun by Bishop Ecclesius in 527, when Ravenna was under the rule of the Ostrogoths, and completed by the twenty-seventh Bishop of Ravenna, Maximian, in 546 during the Byzantine Exarchate of Ravenna. The architect or architects of the church is unknown.

The construction of the church was sponsored by a Greek banker, Julius Argentarius, and the final cost amounted to 26,000 solidi (gold pieces). The church has an octagonal plan and combines Roman elements (the dome, shape of doorways, and stepped towers) with Byzantine elements (a polygonal apse, capitals , and narrow bricks). The church is most famous for its wealth of Byzantine mosaics —they are the largest and best preserved mosaics outside of Constantinople.

The central section is surrounded by two superposed ambulatories, or covered passages around a cloister. The upper one, the matrimoneum, was reserved for married women. A series of mosaics in the lunettes above the triforia depict sacrifices from the Old Testament.

On the side walls, the corners, next to the mullioned windows, are mosaics of the Four Evangelists, who are dressed in white under their symbols (angel, lion, ox and eagle). The cross-ribbed vault in the presbytery is richly ornamented with mosaic festoons of leaves, fruit, and flowers that converge on a crown that encircles the Lamb of God.

The crown is supported by four angels, and every surface is covered with a profusion of flowers, stars, birds, and animals, specifically many peacocks. Above the arch , on both sides, two angels hold a disc. Beside them are representations of the cities of Jerusalem and Bethlehem. These two cities symbolize the human race.

Sculpture of the Early Christian Church

Despite an early opposition to monumental sculpture, artists for the early Christian church in the West eventually began producing life-sized sculptures.

Learning Objectives

Differentiate Early Christian sculpture from earlier Roman sculptural traditions

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Early Christians continued the ancient Roman traditions in portrait busts and sarcophagus reliefs , as well as in smaller objects such as the consular diptych .

- Such objects, often in valuable materials, were also the main sculptural traditions of the barbaric civilizations of the Migration period. This may be seen in the hybrid Christian and animal- style productions of Insular art .

- The Carolingian and Ottonian eras witnessed a return to the production of monumental sculpture. By the tenth and eleventh centuries, there are records of several apparently life-size sculptures in Anglo-Saxon churches.

- Monumental crosses sculpted from wood and stone became popular during the ninth and tenth centuries in Germany, Italy, and the British Isles.

Key Terms

- diptych: A pair of linked panels, generally in ivory, wood, or metal and decorated with rich sculpted decoration.

- sculpture in the round: Free-standing sculpture, such as a statue, that is not attached (except possibly at the base) to any other surface.

The Early Christians were opposed to monumental religious sculpture. Nevertheless, they continued the ancient Roman sculptural traditions in portrait busts and sarcophagus reliefs. Smaller objects, such as consular diptychs, were also part of the Roman traditions that the Early Christians continued.

Small Ivory Reliefs

Consular diptychs were commissioned by consuls elected at the beginning of the year to mark his entry to that post, and were distributed as a commemorative reward to those who supported his candidature or might support him in future.

The oldest consular diptych depicts the consul Probus (406 CE) dressed in the traditional garb of a Roman soldier. Despite showing signs of the growing stylization and abstraction of Late Antiquity , Probus maintains a contraposto pose. Although Christianity had been the state religion of the Roman Empire for over 25 years, a small winged Victory with a laurel wreath poses on a globe that Probus holds in his left hand. However, the standard he holds in his right hand translates as, “In the name of Christ, you always conquer.”

Consular diptych of Probus: Despite showing signs of the growing stylization and abstraction of Late Antiquity, Probus maintains a contraposto pose.

Carolingian art revived ivory carving, often in panels for the treasure bindings of grand illuminated manuscripts , as well as in crozier heads and other small fittings. The subjects were often narrative religious scenes in vertical sections, largely derived from Late Antique paintings and carvings, as were those with more hieratic images derived from consular diptychs and other imperial art.

One surviving example from Reims, France depicts two scenes from the life of Saint Rémy and the Baptism of the Frankish king Clovis. Unlike classical relief figures before Late Antiquity, these figures seem to float rather than stand flatly on the ground .

However, we can also see the Carolingian attempt to recapture classical naturalism with a variety of poses, gestures, and facial expressions among the figures. Interacting in a life-like manner, all the figures are turned to some degree. No one stands in a completely frontal position.

Carolingian treasure binding scenes from the life of Saint Rémy and King Clovis.: Note the Carolingian attempt to recapture classical naturalism with a variety of poses, gestures, and facial expressions among the figures.

The Revival of Monumental Sculpture

However, a production of monumental statues in the courts and major churches in the West began during the Carolingian and Ottonian periods. Charlemagne revived large-scale bronze casting when he created a foundry at Aachen that cast the doors for his palace chapel, which were an imitation of Roman designs. This gradually spread throughout Europe.

There are records of several apparently life-size sculptures in Anglo-Saxon churches by the tenth and eleventh centuries. These sculptures are probably of precious metal around a wooden frame.

One example is the Golden Madonna of Essen (c. 980), a sculpture of the Virgin Mary and the infant Jesus that consistes of a wooden core covered with sheets of thin gold leaf . It is both the oldest known sculpture of the Madonna and the oldest free-standing, medieval sculpture north of the Alps.

It is also the only full-length survivor from what appears to have been a common form of statuary among the wealthiest churches and abbeys of tenth and eleventh century Northern Europe, as well as one of very few sculptures from the Ottonian era.

In the Golden Madonna of Essen, the naturalism of the Graeco-Roman era has all but disappeared. The head of the Madonna is very large in proportion the remainder of her body. Her eyes open widely and dominate her nose and mouth, which seem to dissolve into her face. In an additional departure from classical naturalism, the Baby Jesus appears not so much as an infant but rather as a small adult with an adult facial expression and hand gesture.

Sculpted Crosses

Monumental crosses such as the Gero Crucifix (c. 965–970) were evidently common in the ninth and tenth centuries. The figure appears to be the finest of a number of life-size, German, wood-sculpted crucifixions that appeared in the late Ottonian or early Romanesque period, and later spread to much of Europe.

Charlemagne had a similar crucifix installed in the Palatine Chapel in Aachen around 800 CE. Monumental crucifixes continued to grow in popularity, especially in Germany and Italy. The Gero Crucifix appears to capture a degree of Hellenistic pathos in the twisted body and frowning face of the dead Christ.

Engraved stones were northern traditions that bridged the period of early Christian sculpture. Some examples are Nordic tradition rune stones, the Pictish stones of Scotland, and the high cross reliefs of Christian Great Britain.

Large, stone Celtic crosses, usually erected outside monasteries or churches, first appeared in eighth-century Ireland. The later insular carvings found throughout Britain and Ireland were almost entirely geometrical, as was the decoration on the earliest crosses. By the ninth century, reliefs of human figures were added to the crosses. The largest crosses have many figures in scenes on all surfaces, often from the Old Testament on the east side, and the New Testament on the west, with a Crucifixion at the center of the cross.

Muiredach’s High Cross (tenth century) at Monasterboice is usually regarded as the peak of the Irish crosses. Whereas the Carolingian treasure binding and the Gero Crucifix attempt to recapture the attributes of classical sculptures, the figures on Muiredach’s High Cross lack a sense of naturalism.

Some have large heads that dwarf their bodies, and others stand in fully frontal poses. This departure from the classical paradigm reflects a growing belief that the body was merely a temporary shell for—and therefore inferior to—the soul.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike