12.23: The High Classical Period

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 263989

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Architecture in the Greek High Classical Period

High and Late Classical architecture is distinguished by its adherence to proportion, optical refinements, and its early exploration of monumentality.

Learning Objectives

Identify the departures from traditional Classical Greek architecture in the Temple of Apollo Epicurius, the Tholos of Athena Pronaia, and the Theatre at Epidauros

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Architecture during the Early and High Classical periods was refined and the optical illusions corrected to create the most aesthetically pleasing proportions. The High and Late Classical periods begin to tweak these principles and experiment with monumentality and space .

- Temples during the Late Classical period began to experiment with new architectural designs and decoration. The Tholos of Athena Pronaia at Delphi is a circular shrine with two rings of columns , the outer Doric and the inner Corinthian.

- The Temple of Epicurious at Bassae is noted for its unique ground plan and the use of architectural elements from all three Classical orders: Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian. The temple’s use of architectural decoration and a ground plan demonstrate changing aesthetics .

- The theater in the city of Epidauros is a prime example of advanced engineering skills during this period. The theater is built with refined acoustics that could amplify the sounds on the stage to every one of the theater’s 14,000 spectators.

Key Terms

- skênê: The structure at the back of a theatre stage.

- aniconic: Of, or pertaining to, representations without human or animal form.

- tholos: A circular structure, often a temple.

Classical Greek Architecture Overview

During the Classical period, Greek architecture underwent several significant changes. The columns became more slender, and the entablature lighter during this period.

In the mid-fifth century BCE, the Corinthian column is believed to have made its debut. Gradually, the Corinthian order became more common as the Classical period came to a close, appearing in conjunction with older orders, such as the Doric.

Additionally, architects began to examine proportion and the chromatic effects of Pentelic marble more closely. In the construction of theaters, architects perfected the effects of acoustics through the design and materials used in the seating area.

The architectural refinements perfected during the Late Classical period opened the doors of experimentation with how architecture could define space, an aspect that became the forefront of Hellenistic architecture.

Temples

Throughout the Archaic period, the Greeks experimented with building in stone and slowly developed their concept of the ideal temple. It was decided that the ideal number of columns would be determined by a formula in which twice the number of columns across the front of the temple plus one was the number of columns down each side (2x + 1 = y).

Many temples during the Classical period followed this formula for their peripteral colonnade , although not all. Furthermore, many temples in the Classical period and beyond are noted for the curvature given to the stylobate of the temple that compensated for optical distortions.

Temple of Apollo Epicurius at Bassae

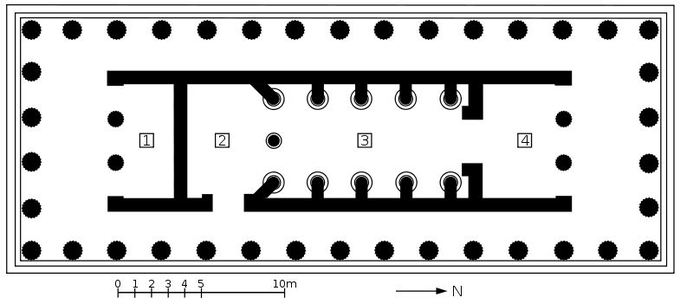

The Temple of Apollo Epicurius at Bassae is a hexastyle temple with fifteen columns down its length. The temple was built by Iktinos, known for his work on the Parthenon, in the second half of the fifth century BCE. The temple’s plan is unusual in many respects.

- The temple is aligned north to south instead of east to west, which accommodates the landscape of the site.

- The temple has a door on the naos that provides access and light to the inner chamber.

- It shares some attributes with the Parthenon, such as a colonnade in the naos. However, in this case the colonnade is a single story, and only the columns of the temple (not the stylobate) have entasis .

- The temple has elements of all three architectural orders and has the earliest known example of a Corinthian capital .

Interestingly, the temple has only one Corinthian column, located in the center of the naos. Experts hypothesize that it was placed in that location to replace the cult statue as an aniconic representation of Apollo.

Tholos of Athena Pronaia

The Tholos of Athena Pronaia at Delphi (380–360 BCE) was built as a sanctuary by Theodoros of Phoenicia. Externally, 20 Doric columns supported a frieze with triglyphs and metopes . The circular wall of the cella was also crowned by a similar frieze, metopes, and triglyphs to a lesser extent.

Inside, a stone bench supported 10 Corinthian style pilasters , all of them attached to the concave surface of the wall. The Corinthian capital was developed in the middle of the fifth century and used minimally until the Hellenistic era; it was later popular with the Romans.

The manifold combination and blending of various architectural styles in the same building was completed through a natural polychromatic effect that resulted from the use of different materials. The materials used included thin slabs of Pentelic marble in the superstructure and limestone at the platform.

When exposed to the air, Pentelic marble acquires a tan color that sets it apart from whiter forms of marble. The building’s roof was also constructed of marble and housed eight female statues carved in sharp and lively motion.

Theater at Epidauros

The large theater located at Epidauros provides an example of the advanced engineering at that time. The theater was designed by Polykleitos the Younger, the son of the sculptor Polykleitos, in the mid-fourth century BCE.

The theater seats up to 14,000 people. Like all Greek theaters, this theatre was built into the hillside, which supports the stadium seating, and the theater overlooks a lush valley and mountainous landscape. The original 34 rows were extended in Roman times by another 21 rows.

As is usual for Greek theatres, the view on a lush landscape behind the skênê is an integral part of the theatre itself and is not to be obscured. The theater is especially well known for its acoustics. A 2007 study indicates that the astonishing acoustic properties may be the result of its advanced design. The rows of limestone seats filter out low-frequency sounds, such as the murmur of the crowd, and amplify high-frequency sounds from the stage.

The Acropolis

The Athenian Acropolis is an ancient citadel in Athens containing the remains of several ancient buildings, including the Parthenon.

Learning Objectives

Summarize the history and structure of the Acropolis of Athens

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The Acropolis, dedicated to the goddess Athena, has played a significant role in the city from the time that the area was first inhabited during the Neolithic era. In recent centuries, its architecture has influenced the design of many public buildings in the Western hemisphere.

- Immediately following the Persian war in the mid-fifth century BCE, the Athenian general and statesman Pericles coordinated the construction of the site’s most important buildings including the Parthenon, the Propylaea, the Erechtheion, and the temple of Athena Nike.

- The structures on the Acropolis incorporated the Cyclopean foundations of older Mycenaean-era structures.

- In its heyday, the Parthenon featured a Doric facade and Ionic frieze interior, while the Doric Propylaea—the gateway to the Acropolis and an art gallery in the Classical era—lacked friezes and pedimental sculptures. The Ionic Erechtheion, believed to have been dedicated to the legendary King Erechtheus, features a porch supported by columnar caryatids . The Temple of Athena Nike, which celebrates Athenian war victories, was built in the Ionic order.

- The sculptures from each of these buildings depict scenes specific to their historical and mythological significance to Athens.

Key Terms

- peripteral: Surrounded by a single row of columns.

- prostyle: Free-standing columns across the front of a building.

- entablature: The area of a temple facade that lies horizontally atop the columns.

- elevation: A geometric projection of a building, or other object, on a plane perpendicular to the horizon.

- Geometric period: An era of abstract and stylized motifs in ancient Greek vase painting and sculpture. The period was centered in Athens and flourished from 900 to 700 BCE.

- Pericles: A prominent and influential Greek statesman, orator, and the general of Athens during the city’s Golden Age—specifically, the time between the Persian and Peloponnesian wars.

- capital: The topmost part of a column.

The Athenian Acropolis

The study of Classical-era architecture is dominated by the study of the construction of the Athenian Acropolis and the development of the Athenian agora . The Acropolis is an ancient citadel located on a high, rocky outcrop above and at the center of the city of Athens. It contains the remains of several ancient buildings of great architectural and historic significance.

The word acropolis comes from the Greek words ἄ (akron, meaning edge or extremity) and π (polis, meaning city). Although there are many other acropoleis in Greece, the significance of the Acropolis of Athens is such that it is commonly known as The Acropolis without qualification.

The Acropolis has played a significant role in the city from the time that the area was first inhabited during the Neolithic era. While there is evidence that the hill was inhabited as far back as the fourth millennium BCE, in the High Classical Period it was Pericles (c. 495–429 BCE) who coordinated the construction of the site’s most important buildings, including the Parthenon, the Propylaea, the Erechtheion, and the temple of Athena Nike.

The buildings on the Acropolis were constructed in the Doric and Ionic orders, with dramatic reliefs adorning many of their pediments , friezes, and metopes .

In recent centuries, its architecture has influenced the design of many public buildings in the Western hemisphere.

Early History

Archaeological evidence shows that the acropolis was once home to a Mycenaean citadel. The citadel’s Cyclopean walls defended the Acropolis for centuries, and still remains today. The Acropolis was continually inhabited, even through the Greek Dark Ages when Mycenaean civilization fell.

It is during the Geometric period that the Acropolis shifted from being the home of a king to being a sanctuary site dedicated to the goddess Athena, whom the people of Athens considered their patron . The Archaic -era Acropolis saw the first stone temple dedicated to Athena, known as the Hekatompedon (Greek for hundred-footed).

This building was built from limestone around 570 to 550 BCE and was a hundred feet long. It has the original home of the olive-wood statue of Athena Polias, known as the Palladium, that was believed to have come from Troy.

In the early fifth century the Persians invaded Greece, and the city of Athens—along with the Acropolis—was destroyed, looted, and burnt to the ground in 480 BCE. Later the Athenians, before the final battle at Plataea, swore an oath that if they won the battle—that if Athena once more protected her city—then the Athenian citizens would leave the Acropolis as it is, destroyed, as a monument to the war. The Athenians did indeed win the war, and the Acropolis was left in ruins for thirty years.

Periclean Revival

It was immediately following the Persian war that the Athenian general and statesman Pericles funded an extensive building program on the Athenian Acropolis. Despite the vow to leave the Acropolis in a state of ruin, the site was rebuilt, incorporating all the remaining old materials into the spaces of the new site.

The building program began in 447 BCE and was completed by 415 BCE. It employed the most famous architects and artists of the age and its sculpture and buildings were designed to complement and be in dialog with one another.

The Parthenon

The Parthenon represents a culmination of style in Greek temple architecture. The optical refinements found in the Parthenon—the slight curve given to the whole building and the ideal placement of the metopes and triglyphs over the column capitals —represent the Greek desire to achieve a perfect and harmonious design known as symmetria.

While the artist Phidias was in charge of the overall plan of the Acropolis, the architects Iktinos and Kallikrates designed and oversaw the construction of the Parthenon (447–438 BCE), the temple dedicated to Athena. The Parthenon is built completely from Pentalic marble, although parts of its foundations are limestone from a pre-480 BCE temple that was never completed.

The design of the Parthenon varies slightly from the basic temple ground plan . The temple is peripteral , and so is surrounded by a row of columns. In front of both the pronaos (porch) and opisthodomos is a single row of prostyle columns.

The opisthodomos is large, accounting for the size of the treasury of the Delian League, which Pericles moved from Delos to the Parthenon. The pronaos is so small it is almost non-existent. Inside the naos is a two-story row of columns around the interior, and set in front of the columns is the cult statue of Athena. It is the most important surviving building of Classical Greece.

The Parthenon’s elevation has been streamlined and shows a mix of Doric and Ionic elements. The exterior Doric columns are more slender and their capitals are rigid and cone-like. The entablature also appears smaller and less weighty then earlier Doric temples. The exterior of the temple has a Doric frieze consisting of metopes and triglyphs.

Inside the temple are Ionic columns and an Ionic frieze that wraps around the exterior of the interior building. Finally, instead of the columns, the whole building has an entasis , a slight curve to compensate for the human eye. If the building was built perfectly at right angles and with straight eyes, the human eye would see the lines as curved. In order for the Parthenon to appear straight to the eye, Iktinos and Kallikrates added curvature to the building that the eye would interpret as straight.

The sculpted reliefs on the Parthenon’s metopes are both decorative and symbolic, and relate stories of the Greeks against the others. Each side depicts a different set of battles.

- Over the entrance on the east side is a Gigantomachy , depicting the battle between the giants and the Olympian gods.

- The west side depicts an Amazonomachy, showing a battle between the Athenians and the Amazons.

- The north side depicts scenes of the Greek sack of Troy at the end of the Trojan War.

- The south side depicts a Centauromachy, or a battle with centaurs. The Centauromachy depicts the mythical battle between the Greek Lapiths and the Centaurs that occurred during a Lapith wedding.

These scenes are the most preserved of the metopes and demonstrate how Phidias mastered fitting episodic narrative into square spaces.

The interior Ionic processional frieze wraps around the exterior walls of the naos. While the frieze may depict a mythical or historical procession, many scholars believe that it depicts a Panatheniac procession.

The Panathenaic procession occurred yearly through the city, leading from the Dipylon Gate to the Acropolis and culminating in a ritual changing of the peplos worn by the ancient olive-wood statue of Athena. The processional scene begins in the southwest corner and wraps around the building in both directions before culminating in the middle of the of the west wall.

It begins with images of horsemen preparing their mounts, followed by riders and chariots, Athenian youth with sacrificial animals, elders and maidens, then the gods before culminating at the central event. The central image depicts Athenian maidens with textiles, replacing the old peplos with a new one.

The east and west pediments depict scenes from the life of Athena and the east pediment is better preserved than the west; fortunately, both were described by ancient writers. The west pediment depicted the contest between Athena and Poseidon for the patronage of Athens. At the center of the pediment stood Athena and Poseidon, pulling away from each to create a strongly charged, dynamic composition .

The east pediment depicted the birth of Athena. While the central image of Zeus, Athena, and Haphaestus has been lost, the surrounding gods, in various states of reaction, have survived.

The Propylaea

Mnesicles designed the Propylaea (437–432 BCE), the monumental gateway to the Acropolis. It funneled all traffic to the Acropolis onto one gently sloped ramp. The Propylaea created a massive screen wall that was impressive and protective as well as welcoming.

It was designed to appear symmetrical but, in reality, was not. This illusion was created by a colonnade of paired columns that wrapped around the gateway. The southern wing incorporated the original Cyclopean walls from the Mycenaean citadel. This space was truncated but served as dining area for feasting after a sacrifice .

The northern wing was much larger. It was a pinacoteca , where large panel paintings were hung for public viewing. The order of the Propylaea and its columns are Doric, and its decoration is simple—there are no reliefs in the metopes and pediment.

Upon entering the Acropolis from the Propylaea, visitors were greeted by a colossal bronze statue of Athena Promachos (c. 456 BCE), designed by Phidias. Accounts and a few coins minted with images of the statue allow us to conclude that the bronze statue portrayed a fearsome image of a helmeted Athena striding forward, with her shield at her side and her spear raised high, ready to strike.

The Erechtheion

The Erechtheion (421–406 BCE), designed by Mnesicles, is an ancient Greek temple on the north side of the Acropolis. Scholars believe the temple was built in honor of the legendary king Erechtheus.

It was built on the site of the Hekatompedon and over the megaron of the Mycenaean citadel. The odd design of the temple results from the site’s topography and the temple’s incorporation of numerous ancient sites.

The temple housed the Palladium, the ancient olive-wood statue of Athena. It was also believed to be the site of the contest between Athena and Poseidon, and so displayed an olive tree, a salt-water well, and the marks from Poseidon’s trident to the faithful.

Shrines to the mythical kings of Athens, Cecrops and Erechteus—who gives the temple its name—were also found within the Erechtheion. Because of its mythic significance and its religious relics , the Erechtheion was the ending site of the Panathenaic festival, when the peplos on the olive-wood statue of Athena was annually replaced with new clothing with due pomp and ritual.

A porch on the south side of the Erechtheion is known as the Porch of the Caryatids, or the Porch of the Maidens. Six, towering, sculpted women (caryatids) support the entablature. The women replace the columns, yet look columnar themselves. Their drapery, especially over their weight-bearing leg, is long and linear, creating a parallel to the fluting on an Ionic column.

While they stand in similar poses, each statue has its own stance, facial features, hair, and drapery. They carry egg-and-dart capitals on their heads, much as women throughout history have carried baskets. Between their heads and this capital is a sculpted cushion, which gives the appearance of softening the load of the weight of the building.

The sculpted columnar form of the caryatids is named after the women of the town of Kayrai, a small town near and allied to Sparta. At one point during the Persian Wars the town betrayed Athens to the Persians. In retaliation, the Athenians sacked their city, killing the men and enslaving the women and children. Thus, the caryatids depicted on the Acropolis are symbolic representations of the full power of Athenian authority over Greece and the punishment of traitors.

The Temple of Athena Nike

The Temple of Athena Nike (427–425 BCE), designed by Kallikrates in honor of the goddess of victory, stands on the parapet of the Acropolis, to the southwest and to the right of the Propylaea. The temple is a small Ionic temple that consists of a single naos, where a cult statue stood fronted by four piers . The four piers aligned to the four Ionic prostyle columns of the pronaos. Both the pronaos and opisthodomos are very small, nearly non-existent, and are defined by their four prostyle columns.

The continuous frieze around the temple depicts battle scenes from Greek history. These representations include battles from the Persian and Peloponnesian Wars, including a cavalry scene from the Battle at Marathon and the Greek victory over the Persians at the Battle of Plataea.

The scenes on the Temple of Athena Nike are similar to the battle scenes on the Parthenon, which represented Greek dominance over non-Greeks and foreigners in mythical allegory . The scenes depicted on the frieze of the Temple of Athena Nike frieze display Greek and Athenian dominance and military power throughout historical events.

A parapet was added on the balustrade to protect visitors from falling down the steep hillside. Images of Nike, such as Nike Adjusting Her Sandal, are carved in relief.

In this scene Nike is portrayed standing on one leg as she bends over a raised foot and knee to adjust her sandal. Her body is depicted in the new High Classical style. Unlike Archaic sculpture, this scene actually depicts Nike’s body. Her body and muscles are clearly distinguished underneath her transparent yet heavy clothing.

This style, known as wet drapery , allows sculptors to depict the body of a woman while still preserving the modesty of the female figure. Although Nike’s body is visible, she remains fully clothed. This style is found elsewhere on the Acropolis, such as on the caryatids and on the women in the Parthenon’s pediment.

Urban Planning in the Greek High Classical Period

Hippodamus of Miletus is considered the father of rational city planning, and the city of Priene is a prime example of his grid-planned cities.

Learning Objectives

Describe the role of Hipposamus of Miletus in the development of grid-planned cities in Classical Greece

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- As an architect and city planner, Hippodamus of Miletus (fifth century BCE) developed an urban plan based on streets that intersect at right angles, known as the Hippodamian Plan.

- The Hippodamian Plan is based on a grid of right angles and the allocation of public and private space . The center of the city is the home of the city’s most important civic public spaces, including the agora , the bouleuterion , theaters, and temples. Private rooms surround the city’s public areas.

- Since the Hippodamian Plan is based on angles and measurements, it can be laid out uniformly over any kind of terrain. In the city of Priene, the plan is laid out over a sloping hillside, and the terrain is terraced to fit into the rational network of houses, streets, and public buildings.

Key Terms

- Ionia: An ancient Greek settlement on the west coast of Asia Minor inhabited by one of the four, main Hellenic tribes.

- bouleuterion: A building that housed the council of citizens in Ancient Greece; an assembly hall.

- grid plan: A type of city plan in which streets run at right angles to each other.

Hippodamus of Miletus

Although the idea of the grid was present in early Greek city planning, it was not pervasive prior to the fifth century BCE. Following the Persian and Peloponnesian Wars, many cities were left decimated and in need of rebuilding. Before rational city planning, cities grew organically and often radiated out from a central point, such as the Acropolis and Agora at the center of Athens.

Hippodamus of Miletus on the Ionian coast (the western coast of modern Turkey) was an architect and urban planner who lived between 498 and 408 BCE. He is considered the father of urban planning, and his name is given to the grid layout of city planning, known as the Hippodamian plan.

His plans of Greek cities were characterized by order and regularity in contrast to the intricacy and confusion common to cities of that period. He is seen as the originator of the idea that a town plan might formally embody and clarify a rational social order.

The Hippodamian plan is now known as a grid plan formed by streets intersecting at right angles. Hippodamus helped rebuild many Greek cities using this plan, and the construction was exported to newly settled Greek colonies. It was later adopted by Alexander the Great for the cities he founded and was eventually used extensively by the Romans for their colonies.

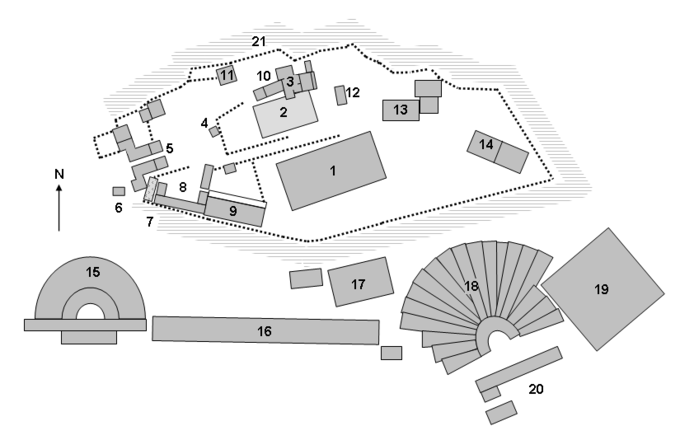

The plan not only encompassed the grid pattern for the streets but also designated a standard size for city blocks and allocated public and private space. Typically the public spaces of the Greeks’ agorae and theaters were located at the center of the city. Additional space would be cleared for gymnasiums and stadiums. The acropolis, the highest part of the city, was always reserved for the city’s most important temples.

Priene and Miletus

The city of Priene, located near Miletus on the Ionian coast, is a prime example of the Hippodamian plan. The city is located on a hillside, and the urban plan forces structure onto the natural landscape. The city’s grid-planned streets divide the sloping hillside into blocks, which are further divided into lots for private housing.

In the middle of the city were many public buildings. The agora was the central component of the city. Its colonnaded stoa bounded the public space to the north. The agora stretched the length of six city blocks and was flanked on its southern side by the Temple of Zeus.

North of the stoa was the bouleuterion, the assembly hall, and a small theatre. A Temple of Athena was located just northwest of the agora. Blocks of housing surrounded the agora. Down the slope from them on level ground were the gymnasium and stadium. Above the city, high on a hillside, was the city’s acropolis.

The plan of Priene follows the rational grid plan established by Hippodamus and demonstrates its function, even when laid over the rocky and hilly terrain. The city’s location on a hillside did not constrict its uniformity or the allocation of public and private space. Instead, the rational plan of Priene allowed for access to multiple sites of the city and easy navigation through the city.

In Hippodamus’ home city of Miletus, the grid plan would become the model of urban planning followed by the Romans. What is most impressive is its wide central area, which is kept unsettled according to his macro-scale urban estimation and in time evolved to the Agora, the center of both the city and society.

Stelae in the Greek High Classical Period

Large, relief-carved stelae became the new funerary markers in Greece during the High Classical period.

Learning Objectives

Describe the function of stelae in High Classical Greek sculpture

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Funerary stelae were large and rectangular. They were often topped by pediments that were often, although not always, supported by columns . Stelae were originally painted and in some cases adorned with metal props such as spears.

- The funerary stelae of Classical Greece are idealized portraits that attempt to relate the character and social position of the dead through attributes depicted on the grave marker. Examples include a warrior depicted in battle or a woman adorning herself in jewelry.

- The reliefs on funerary stelae followed the stylistic characteristics of the Classical period. The bodies of the men are well modeled and, if standing, they often stand with contrapposto . Drapery is often portrayed in the wet-drapery style , which allows for the form of the body to be shown.

- The funerary stelae of children often depict companion animals, such as doves and other birds, which might have had symbolic connections with the afterlife.

Key Terms

- naiskos: A small temple made in the Classical order with columns or pillars and pediment.

- Kerameikos: An area of Ancient Athens located northwest of the Acropolis on either side of the Dipylon Gate. The location is known as the potter’s quarter.

- stele: A tall, slender stone monument, often with writing carved into its surface

Funerary Stelae

A stele (plural: stelae) is a large slab of stone or wood erected for commemorative and funerary purposes. The stelae of ancient Greece replaced the funerary markers of the Geometric kraters and amphorae, and the Archaic kouroi and korai of the Classical period.

The stelae were wide and tall and were Classical-style portraits. While the figures were still idealized, they were meant to represent specific individuals. Stelae were inscribed with the name of the dead and often the names of the relatives. Most stelae are rectangular and often topped with a pediment. Columns often, but not always appear on each side, seemingly to support the pediment. Stelae in this faux-architectural style assume the form of a funerary temple called a naiskos . An inscription would be located on the pediment or below the image, in which case the pediment was painted, plain, or decorated simply with geometric designs.

The figures depicted on Classical-era stelae are in the same style and manner seen in Classical sculpture and on sculptural decoration of architecture, such as a temple’s pediments and frieze . Stelae as grave markers became popular around 430 BCE, coinciding with the beginning of the Peloponnesian War. Each stele is unique for its attempts to individualize and characterize the attributes and personality of the dead.

Grave Stele of Hegeso

The Grave Stele of Hegeso from the Kerameikos Cemetery outside of Athens depicts a seated woman. The stele dates to 400 BCE, and the woman fits the stylistic representation of women at this time.

Hegeso sits on a chair with her feet resting on a footstool. She is elegantly dressed in long, flowing drapery. A female attendant in simple dress stands before her holding a small box, from which Hegeso chooses jewelry. The jewelry is now absent because it was only a painted detail, as opposed to carved in relief.

Both women wear transparent clothing that clings to their body to relieve their feminine form, although the clothing is more revealing on Hegeso than her servant. This style, known as wet drapery , also appears on the Temple of Athena Nike in Athens. Both figures are expressionless and emotionless.

Grave Stele of an Athlete

The Grave Stele of an Athlete (early fourth century BCE), from the island of Delos, depicts a male athlete receiving lekythos of oil from a male youth. The athlete’s body is reminiscent of Polykleitos’s Doryphoros. It is athletic, and the muscles are defined through modeling instead of lines .

He stands in a contrapposto pose with a cocked head, reaching for the flask held by the young attendant. The youth’s age is defined not by his well-built body (which is very similar to that of the athlete) but by his diminutive size.

Grave Stele of Dexileos

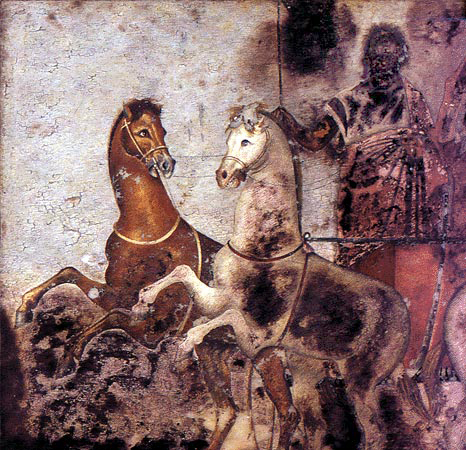

The Grave Stele of Dexileos (390 BCE) in the Kerameikos Cemetery of Athens is another demonstration of how stele reliefs reflect the sculpture style and motifs of the period. This stele recalls the carved relief of Athenian horsemen from the Ionic frieze of the Parthenon.

Dexileos rides astride a rearing horse, charging down an enemy. The inscription refers to his early death in a battle against the Corinthians. He probably originally held a metal spear in his raised hand. The two figures, Dexileos and the Corinthian, are dressed differently. The Corinthian’s nudity signifies his difference from the civilized Athenian who is properly clothed. Dexileos’s flying cape and rearing horse add drama to scene, which despite its content, is oddly expressionless due to emotionless faces of the characters.

Grave Stele of a Little Girl

While the above stelae commemorate adults, grave stelae also commemorate children. The Grave Stele of a Little Girl (450–440 BCE), which lacks a pediment and allows the deceased to assume most of the space , depicts a young child holding two doves, presumably her pets.

One bird perches in her hands, while the other seems to cuddle next to her and affectionately peck at her mouth. She bows her head toward both doves, wearing a solemn facial expression, as if bidding the animals farewell. Such images of children and companion animals are common subject matter on grave stelae of the Classical era.

The doves’ ability to fly connected them to death and the afterlife. Some experts theorize that doves were believed to be able to communicate with those in the afterlife. Like the women on the Grave Stele of Hegeso, the child’s clothing assumes the wet-drapery style to accentuate the contours of her body while allowing her to maintain feminine modesty.

Painting in the Greek High Classical Period

Panel and tomb paintings from the High Classical Period depict natural figures with high plasticity and dynamic compositions.

Learning Objectives

Describe the styles of painting that developed through the High Classical period as seen in panel and tomb paintings

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Few examples of panel, fresco , and wall painting survive due to their organic materials. However, the examples that do survive from the Archaic , Classical , and Late Classical periods demonstrate the same development of the figure—from stiff, rigid images to dynamic scenes of natural figures.

- The painter Apollodorus was considered one of the most talented painters in the Classical period. He developed a technique to depict shadows and depth known to the Greeks as skiagraphia, which is similar to the Renaissance use of chiaroscuro .

- The Roman Alexander Mosaic is believed to be a copy of a large-scale Greek fresco or panel painting from the late fourth century BCE. Its remarkable detail and identifiable characteristics of Alexander the Great amidst a dynamic battle point to the skill of Greek painters at the end of the Classical era.

Key Terms

- symposium: A drinking party, especially one with intellectual discussion, in ancient Greece.

- chiaroscuro: An artistic technique popularized during the Renaissance, referring to the use of exaggerated light contrasts in order to create the illusion of volume.

Classical Greece was a 200-year period in Greek culture that lasted from the fifth through fourth centuries BCE. This Classical period, following the Archaic period and succeeded by the Hellenistic period, had a powerful influence on the Roman Empire and greatly influenced the foundations of the Western Civilization . Much of modern Western politics and artistic thought, such as architecture, scientific thought, literature, and philosophy, derives from this period of Greek history.

Panel Painting

Panel painting is the painting on flat panels of wood, either a large single piece or several joined together. Because of their organic nature many panel paintings no longer exist. Panel paintings were usually done in encaustic or tempera and were displayed in the interior of public buildings, such as in the pinacoteca of the Propylaea of the Athenian Acropolis.

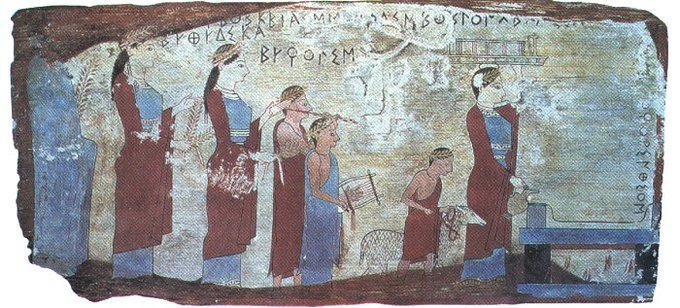

The earliest known panel paintings are the Pitsa Panels that date to the Archaic period between 540 and 530 BCE; however, panel painting continued throughout the Classical Period.

The painter Apollodorus was considered by the Greeks and Romans to be one of the best painters of the Early Classical period, although none of his work survived. He is credited for the use of creating shadows by a technique known as skiagraphia. The technique layers crosshatching and contour liners to add perspective to the scene and is similar to the Renaissance technique of chiaroscuro.

Tomb Painting

Tomb painting was another popular method of painting, which due to its fragile nature has often not survived. However, a few examples do remain, including the 480 BCE Tomb of the Diver and the wall paintings from the royal Macedonian tombs in Vergina that date to the mid-fourth century BCE. A comparison between the paintings demonstrate how painting followed sculptural development in regards to the rendering of the human body.

The Tomb of the Diver is from a small necropolis in Paestum, Italy, which was then the Greek colony of Poseidonia, and dates from the beginning of the Classical period. The tomb depicts a symposium scene on its walls and an image of diver on the inside of the covering slab.

The images are painted in true fresco with a limestone mortar. The scene of the diver is simple image with a small landscape of trees, water, and the diver’s platform. The diver is nude and his body is simply defined through the use of line and color. The bodies of the men at the symposium more accurately demonstrate an Archaic reliance on line to model the form of the body and the draping of their clothing.

Compared to the wall paintings from the tombs at Vergina, the Early Classical tomb painting is static and rather Archaic. The frescos from Vergina depict figures in a full-painted version of the High Classical style .

For example, there is an image believed to depict King Philip II on a chariot pulled by two horses. The fresco is poorly preserved but one is able to see on Philip’s horse the modeling of the animals produced by the color shading and a suggestion of perspective when looking at the chariot. The artist relies on the shades and hues of his paints to create depth and a life-like feeling in the painting.

One of the quintessential wall paintings at Vergina is Hades Abducting Persephone. The painted scene appears similar to the Late Classical sculptural style and the dynamic, emotion-filled composition seems to predict the style of Hellenistic sculpture.

The scene depicts Hades on his chariot, grasping on to Persephone’s nude torso as the pair ride away. The colors are faded and faint, but the bright red drapery worn by Persephone is still easily identifiable. Lines and shading emphasize its folds.

The style appears almost impressionistic, especially when examining Persephone’s face and hair. Persephone and Hades create a tension filled chiastic composition, as Hades races to the left, against the pull of Persephone’s outward, desperate reach to the right.

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedonia (356–323 BCE), better known as Alexander the Great, very carefully controlled and crafted his portraiture. In order to maintain control and stability in his empire, he had to ensure that his people recognized him and his authority.

Because of this, Alexander’s portrait was set when he was very young, most likely in his teens, and it never varied throughout his life. To further control his portrait types, Alexander hired artists in different media such as painting, sculpture, and gem cutting to design and promote the portrait style of the medium. In this way, Alexander used art and artisans for their propagandistic value to support and provide a face and legitimacy to his rule.

Alexander Mosaic

The Alexander Mosaic is a Roman floor mosaic from approximately 100 BCE that was excavated from the House of the Faun in Pompeii. The mosaic depicts the Battle of Issus that occurred between the troops of Alexander the Great and King Darius III of Persia. The mosaic is believed to be a copy of a large-scale panel painting by Aristides of Thebes, or a fresco by the Philoxenos of Eretria from the late fourth century BCE.

The mosaic is remarkable. It depicts a keen sense of detail, dramatically unfolds the drama of the battle, and demonstrates the use of perspective and foreshortening . The two main characters of the battle are easily distinguishable and this portrait of Alexander may be one of his most recognizable. He wears a breastplate and an aegis , and his hair is characteristically tousled. He rides into battle on his horse, Bucephalo, leading his troops. Alexander’s gaze remains focused on Darius and he appears calm and in control, despite the hectic battle happening around him.

Darius III, on the other hand, commands the battle in desperation from his chariot, as his charioteer removes them from battle. His horses flee under the whip of the charioteer and Darius leans outward, stretching out a hand having just thrown a spear. His body position contradicts the motion of his chariot, creating tension between himself and his flight.

Other details in the mosaic include the expressions of the soldiers and the horses, such as a collapsed horse and his rider in the center of the battle, to a terrified fallen Persian, whose expression is reflected on his shield.

The shading and play of light in the mosaic, reflects the use of light and shadow in the original painting to create a realistic, three-dimensional space . Horses and soldiers are shown in multiple perspectives from profile, to three quarter, to frontal, and one horse even faces the audience with his rump. The careful shading within the mosaic tesserae models the characters to give the figures mass and volume .

Sculpture in the Greek High Classical Period

High Classical sculpture demonstrates the shifting style in Greek sculptural work as figures became more dynamic and less static.

Learning Objectives

Compare and contrast the styles of Polykleitos, Phidias, and Myron during the High Classical period

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- After mastering the portrayal of naturalistic bodies from stone, Greek sculptors began to experiment with new poses that expanded the repertoire of Greek art. The sculptures of this later period are moving away from the Classical characteristics they still maintain: idealism and the Severe style .

- Polykleitos is most well known for his Canon, depicted in the Doryphoros, but is also known for his Diadumenos and Discophoros. These two, sculpted athletes are also done in accordance to his canon and are depicted in contrapposto with chiastic poses.

- Phidias was one of the most renowned sculptors his time. He oversaw the sculptural program for the Athenian Acropolis and is also known for his giant chryselephantine cult statues of Zeus and Athena Parthenos.

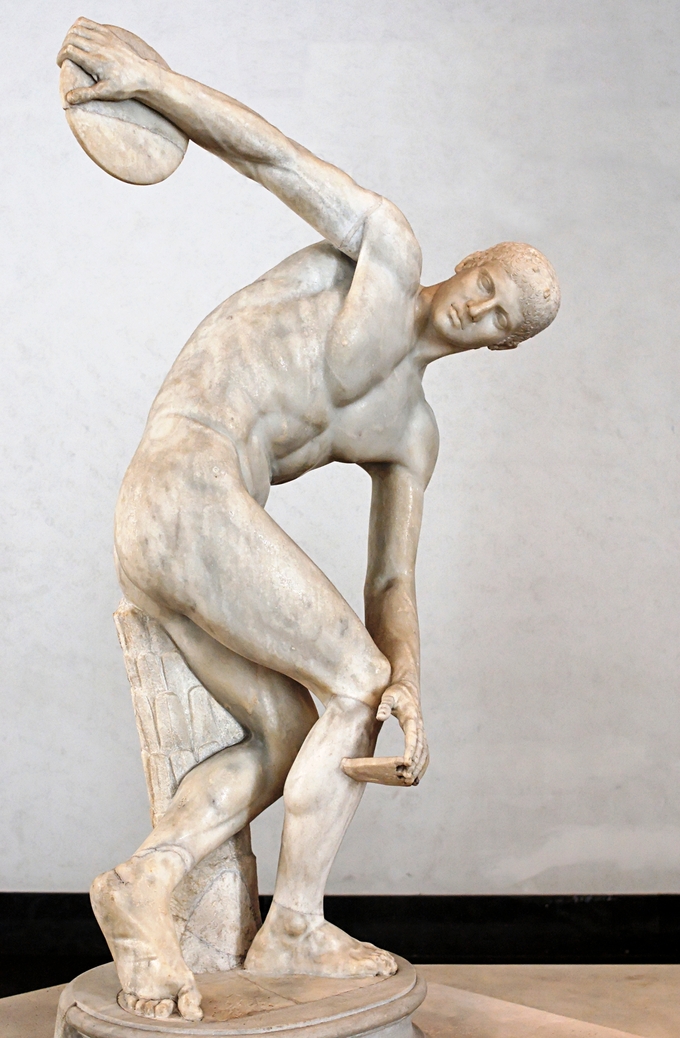

- Myron is a bronze sculptor of the High Classical period. His statues are known for being imbued with potential energy. His Discobolos is poised to spring, preparing to throw a discus. While still idealized, the figure appears to be frozen in an action of intense movement.

Key Terms

- chryselephantine: Made of gold and ivory.

- aegis: An attribute of Zeus or Athena, usually represented as a goatskin shield.

Polykleitos

Polykleitos was a famous Greek sculptor who worked in bronze. He was also an art theorist who developed a canon of proportion (called the Canon) that is demonstrated in his statue of Doryphoros (Spear Bearer) Many of Polykleitos’s bronze statues from the Classical period, including the Doryphoros, survive only as Roman copies executed in marble. Polykleitos, along with Phidias, is thought to have created the style recognized as Classical Greek sculpture.

Another example of the Canon at work is seen in Polykleitos’s statue of Diadumenos, a youth trying on a headband, and his statue Discophoros, a discus bearer. Both Roman marble copies depict athletic, nude, male figures.

The bodies of the two figures are idealized. The nudity allows the harmony of parts, or symmetria, to easily be seen and illustrates the principles discussed in the Canon. The Canon focused on the proportion of parts of the body in relationship to each other to create the ideal male form . Both statues demonstrate fine proportion, ideal balance, and the definable parts of the body.

The athletes are shown in contrapposto stances. The Discophoros shifts his weight to his left leg. His hips and the slightly forward lean toward his right leg exaggerate the weight shift. The figure is balanced on his left leg, which is drawn back, and the rest of his body appropriately responds to this stance.

The Diadumenos also stands in contrapposto, although his movement seems more forward and stable than that of the Discophoros. He ties on a band that identifies him as a winner in an athletic contest. His raised arms add a new dynamic component to the composition .

The Discophoros and Diadumenos, along with the Doryphoros, demonstrate the flexibility of composition based on the Canon and the innate liveliness produced by contrapposto postures. Despite the lively aspects and unique poses of the figures, all three still retain the Severe style and expressionless face of early Greek sculpture.

Polykleitos not only worked in bronze but is also known for his chryselephantine cult statue of Hera at Argos, which in ancient times was compared to Phidias’ colossal chryselephantine cult statues.

Phidias

Phidias was the sculptor and artistic director of the Athenian Acropolis and oversaw the sculptural program of all the Acropolis’ buildings. He was considered one of the greatest sculptors of his time and he created monumental cult statues of gold and ivory for city-states across Greece.

Phidias is well known for the Athena Parthenos, the colossal cult statue in the naos of the Parthenon. While the statue has been lost, written accounts and reproductions (miniatures and representations on coins and gems) provide us with an idea of how the sculpture appeared.

It was made out of ivory, silver, and gold and had a wooden core support. Athena stood crowned, wearing her helmet and aegis . Her shield stood upright at her left side and her left hand rested on it while in her right hand she held a statue of Nike. An artist’s reconstruction is housed in the Parthenon in Nashville.

Before he created the statue of Athena Parthenos for Athens, Phidias was best known for his chryselephantine statue of Zeus at Olympia, which was considered one of the wonders of the world. The statue of Zeus at Olympia is said to have been 39 feet tall chryselephantine statue.

As with Athena Parthenos, not much is known for sure about how the statue looked, although written accounts and marble and coinage copies provide possible ideas. Besides being built on a colossal scale, reports indicate that the figure of Zeus was seated and held a scepter and a statue of Nike. An eagle was perched either at his side or on his scepter.

Besides being decorated with gold and ivory, the sculpture was further embellished with ebony and previous stones. An artist’s conception of the colossal sculpture resides in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia.

Myron

The Athenian artist Myron also produced bronze sculptures during the mid-fifth century BCE. His most famous work is of the Diskobolos, or discus thrower (not to be confused with Polykletios’ discus bearer, Discophoros). The Diskobolos shows a young, athletic male nude with a Severe-style face. His body holds a contrapposto pose; one leg bears his weight, while the other is relaxed. A relaxed arm balances his body and the other arm tenses, preparing to let go of the disc. The Diskobols demonstrates a dynamic, chiastic composition that relies on diagonal lines to move the eye about the sculpture.

This figure represents another new element in Classical sculpture—the illustration of the potential for energy. His energy appears wound up, waiting for the figure to release it. The statue depicts a swift and transitory moment and that is frozen at a precise moment to exhibit the harmony, balance, and rhythm perfected by both the athlete and the artist.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- File:Bassai Temple of Apollo Plan.svg - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.Wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Bassai_Temple_of_Apollo_Plan.svg&page=1. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Epidaure theatre paysage 2009. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Epidaure_theatre_paysage_2009.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Tholos Athena Pronaia. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tholos_Athena_Pronaia.JPG. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ancient Greek Temple. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Greek_temple. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Tholos of Delphi. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Tholos_of_Delphi. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Bassae. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Bassae. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Epidaurus. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Epidaurus. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Delphi. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Delphi%23Tholos. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Aniconic. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/aniconic. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Tholos. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/tholos. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Erechtheion.jpeg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AteneEretteoDaSW.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- temple-of-athena-nike.jpeg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Temple_of_Athena_Nike.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- temple-of-athena-nike-plan.gif. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Temple-of-Athena-Nike-Plan.gif. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- erechtheum-porch.jpeg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: tinyurl.com/jzpgn33. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- acma-973-nike-sandale-1.jpeg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Temple_of_Athena_Nike#/media/File:ACMA_973_Nik%C3%A8_sandale_1.JPG. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- elgin-marbles-frieze.jpeg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Elgin_marbles_frieze.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Acropolis 2 (pixinn.net). Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Acropolis_2_(pixinn.net).jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- propylaea-06.jpeg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Propylaea_06.JPG. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- uth-metope-27-parthenon-bm.jpeg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:South_metope_27_Parthenon_BM.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- AcropolisatathensSitePlan. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AcropolisatathensSitePlan.png. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- px-the-parthenon-in-athens.jpeg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Parthenon_in_Athens.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 640px-Elgin_Marbles_east_pediment.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=439402. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Elgin Marbles. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Elgin_Marbles. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Hekatompedon Temple. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Hekatompedon_temple. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- The Propylaea and the Erechtheion. Provided by: Boundless Learning. Located at: www.boundless.com/atoms/5714. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- The Temple of Athena Nike. Provided by: Boundless Learning. Located at: www.boundless.com/atoms/5328. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- The Parthenon. Provided by: Boundless Learning. Located at: www.boundless.com/atoms/3534. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Palladium (mythology). Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Palladium_(mythology). License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Athena Polias. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Athena_Polias. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Acropolis of Athens. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Acropolis_of_Athens. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Pericles. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Pericles. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Geometric Period. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/geometric%20period. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 374px-Miletos_stadsplan_400.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8277556. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Priene Bouleuterion 2009 04 28. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Priene_Bouleuterion_2009_04_28.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Miletus. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Miletus. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Grid Plan. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/grid_plan. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Hippodamus of Miletus. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Hippodamus_of_Miletus. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Urban Planning. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Urban_planning#History. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Priene. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Priene. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Hippodamus of Miletus. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Hippodamus_of_Miletus. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Bouleuterion. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/bouleuterion. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ionia. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Ionia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Stele youth BM 625. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Stele_youth_BM_625.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Dexileos. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dexileos.JPG. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- NAMA Stu00e8le d'Hu00e8gu00e8su00f4. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:NAMA_St%C3%A8le_d'H%C3%A8g%C3%A8s%C3%B4.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 4427437652_4babd4dc28_z.jpg. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/italintheheart/4427437652. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Naiskos. Provided by: WIkipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Naiskos. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Tweeting from the Getty Villa...and Cooing, Hooting, and Squawking. Provided by: The Iris: Behind the Scenes at the Getty. Located at: http://blogs.getty.edu/iris/tweeting-from-the-getty-villa/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Grave Stele of Hegeso. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Grave_Stele_of_Hegeso. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Grave Stele of a Little Girl. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/italintheheart/4427437652. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Stele. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/stele. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Kerameikos. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Kerameikos. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Greekreligion-animalsacrifice-corinth-6C-BCE. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Greekreligion-animalsacrifice-corinth-6C-BCE.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Vergina royal tomb - fresco. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vergina_royal_tomb_-_fresco.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Paestum tombeau plongeur c1. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Paestum_tombeau_plongeur_c1.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Painting vergina. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Painting_vergina.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- issus-alexander.jpeg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Issus_-_Alexander.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Pitsa Panels. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Pitsa_panels. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Apollodorus (Painter). Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Apollodorus_(painter). License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Mosaic. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosaic. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Alexander the Great. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_the_Great. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Paintings, Macedonian Court Art, and the Alexander Mosaic. Provided by: Boundless Learning. Located at: www.boundless.com/atoms/11064. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ancient Greek Art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Greek_art%23Painting. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Vergina. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Vergina. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Tomb of the Diver. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Tomb_of_the_Diver. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Classical Greece. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Classical_Greece. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Symposium. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/symposium. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Chiaroscuro. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/chiaroscuro. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Discophoros BM. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Discophoros_BM.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- athena-parthenos-lequire.jpeg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15363521. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Met, roman, fragments of a marblke statue of diadoumenos, flavian period, 69-96 ca.. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Met,_roman,_fragments_of_a_marblke_statue_of_diadoumenos,_flavian_period,_69-96_ca..JPG. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Zeus_Hermitage_St._Petersburg_20021009.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=495992. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Discobolus Lancelotti Massimo. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Discobolus_Lancelotti_Massimo.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ancient Greek Art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Greek_art%23Monumental_sculpture. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- The Parthenon. Provided by: Boundless Learning. Located at: www.boundless.com/atoms/3534. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Statue of Zeus at Olympia. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Statue_of_Zeus_at_Olympia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Discobolus. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Discobolus. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Diadumenos. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Diadumenos. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Myron. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Myron. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Phidias. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Phidias. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Chryselephantine. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Chryselephantine. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Polykleitos. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Polykleitos. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike