12.5: Mesopotamia

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 263971

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The Mesopotamian Cultures

Sumer was an ancient Chalcolithic civilization that saw its artistic styles change throughout different periods in its history.

Learning Objectives

Discuss the historical importance of the various civilizations that existed in Mesopotamia

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The Eridu economy produced abundant food, which allowed its inhabitants to settle in one location and form a labor force specializing in diverse arts and crafts.

- Writing produced during the early Sumerian period suggest the abundance of pottery and other artistic traditions.

- Elements of the early Sumerian culture spread through a large area of the Near and Middle East.

- The Sumerian city states rose to power during the prehistorical Ubaid and Uruk periods.

Key Terms

- theocratic:A form of government in which a deity is officially recognized as the civil ruler. Official policy is governed by officials regarded as divinely guided, or is pursuant to the doctrine of a particular religion or religious group.

- casting:A sculptural process in which molten material (usually metal) is poured into a mold, allowed to cool and harden, and become a solid object.

- Cuneiform:One of the earliest known forms of written expression that began as a system of pictographs. It emerged in Sumer around the 30th century BC, with predecessors reaching into the late 4th millennium (the Uruk IV period).

- Chalcolithic:Also known as the Copper Age, a phase of the Bronze Age in which the addition of tin to copper to form bronze during smelting remained yet unknown. The Copper Age was originally defined as a transition between the Neolithic and the Bronze Age.

Sumer was an ancient civilization in southern Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) during the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Ages. Although the historical records in the region do not go back much further than ca. 2900 BCE, modern historians believe that Sumer was first settled between ca. 4500 and 4000 BCE by people who may or may not have spoken the Sumerian language. These people, now called the “Ubaidians,” were the first to drain the marshes for agriculture; develop trade; and establish industries including weaving, leatherwork, metalwork , masonry, and pottery.

The Sumerian city of Eridu, which at that time bordered the Persian Gulf, is believed to be the world’s first city. Here, three separate cultures fused—the peasant Ubaidian farmers, the nomadic Semitic-speaking pastoralists (farmers who raise livestock), and fisher folk. The surplus of storable food created by this economy allowed the region’s population to settle in one place, instead of migrating as hunter-gatherers. It also allowed for a much greater population density, which required an extensive labor force and a division of labor with many specialized arts and crafts.

An early form of wedge-shaped writing called cuneiform developed in the early Sumerian period. During this time, cuneiform and pictograms suggest the abundance of pottery and other artistic traditions. In addition to the production of vessels , clay was also used to make tablets for inscribing written documents. Metal also served various purposes during the early Sumerian period. Smiths used a form of casting to create the blades for daggers. On the other hand, softer metals like copper and gold could be hammered into the forms of plates, necklaces, and collars.

By the late fourth millennium BCE, Sumer was divided into about a dozen independent city-states delineated by canals and other boundary makers. At each city center stood a temple dedicated to the particular patron god or goddess of the city. Priestly governors ruled over these temples and were intimately tied to the city’s religious rites.

The Ubaid Period

The Ubaid period is marked by a distinctive style of painted pottery, as seen in the example below, produced domestically on a slow wheel. This style eventually spread throughout the region. During this time, the first settlement in southern Mesopotamia was established at Eridu by farmers who first pioneered irrigation agriculture. Eridu remained an important religious center even after nearby Ur surpassed it in size.

Ubaid pottery

The Uruk Period

The transition from the Ubaid period to the Uruk period is marked by a gradual shift to a great variety of unpainted pottery mass-produced by specialists on fast wheels. The trough below is an example of pottery from this period.

By the time of the Uruk period (ca. 4100–2900 BCE), the volume of trade goods transported along the canals and rivers of southern Mesopotamia facilitated the rise of many large, stratified , temple-centered cities where centralized administrations employed specialized workers. Artifacts of the Uruk civilization have been found over a wide area—from the Taurus Mountains in Turkey, to the Mediterranean Sea in the west, and as far east as Central Iran. The Uruk civilization, exported by Sumerian traders and colonists, had an effect on all surrounding peoples, who gradually developed their own comparable, competing economies and cultures.

Sumerian cities during the Uruk period were probably theocratic and likely headed by priest-kings (ensis), assisted by a council of elders, including both men and women. The later Sumerian pantheon (gods and goddesses) was likely modeled upon this political structure. There is little evidence of institutionalized violence or professional soldiers during the Uruk period. Towns generally lacked fortified walls, suggesting little, if any, need for defense. During this period, Uruk became the most urbanized city in the world, surpassing for the first time 50,000 inhabitants.

Gilgamesh

The earliest king authenticated through archaeological evidence is Enmebaragesi of Kish, whose name is also mentioned in the Gilgamesh epic (ca. 2100 BCE)—leading to the suggestion that Gilgamesh himself might have been a historical king of Uruk. As the Epic of Gilgamesh shows, the second millennium BCE was associated with increased violence. Cities became walled and increased in size as undefended villages in southern Mesopotamia disappeared.

Ceramics in Mesopotamia

The invention of the potter’s wheel in the fourth millennium BCE led to several stylistic shifts and varieties in form of Mesopotamian ceramics.

Learning Objectives

Differentiate Ubaid pottery from later styles in Mesopotamian ceramics

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The invention and evolution of the potter’s wheel allowed individuals to produce vessels at increasing speeds and in increasing numbers.

- Ubaid pottery was more decorative and unique than Uruk pottery.

- As ceramics evolved, shapes and sizes of clay objects became more varied.

- Clay could also be used for writing tablets that could be fired, if the owner believed the text was important.

Key Terms

- ceramics:The craft of making objects from clay.

- throwing:Shaping clay on a potter’s wheel.

- stylus:A writing implement that incises lines into surfaces, such as clay.

- kiln:A special kind of oven used for firing ceramic objects at high temperatures.

Although ceramics developed in East Asia c. 20,000-10,000 BCE, the practice of throwing arose with the invention of the potter’s wheel in Mesopotamia around the fourth millennium BCE. The earliest clay vessels date to the Chalcolithic Era, which is divided into the Ubaid (5000-4000 BCE) and Uruk (4000-3100 BCE) periods.

The Chalcolithic Era

The Ubaid period is marked by a distinctive style of fine quality painted pottery which spread throughout Mesopotamia. Ceramists produced vases, bowls, and small jars domestically on slow wheels, painting unique abstract designs on the fired clay.

Experts differentiate the Ubaid period from the Uruk period by the style of pottery produced in each era. During the Uruk period, the potter’s wheel advanced to allow for faster speeds. As such, ceramists could produce pottery more quickly, leading to the mass production of standardized, unpainted styles of vessels.

The Akkiadian Empire

As the Akkadian Empire overtook the Sumerian city-states , ceramists continued to produce bowls, vases, jars, and other objects in a variety of shapes and sizes. Like Uruk pottery, the surfaces of these objects were left unpainted, although some vessels appear to have a form of abstract reliefs on the surface. This photograph displays the various forms (including a form that resembles a present-day cake stand) that pottery took during the Akkadian Empire.

Ur III

The Third Ur Dynasty , better known as Ur III, witnessed the continuation of unpainted ceramic vessels that took a variety of forms. This photograph depicts an urn that resembles today’s flower vases, as well as bowls, cups, and a smaller vase.

As in previous eras, clay was also used to produce writing tablets that were incised with styluses fashioned from blunted reeds. Often, tablets were used for record-keeping (the ancient version of an office memo). Like other ceramic objects, tablets could be fired in a kiln to produce a permanent form if the text was believed significant enough to preserve. The tablets in the photograph below contain information about farm animals and workers.

Babylonian Ceramics

Pottery produced during the “Old” Babylonian period shows a return to painted abstract designs and increased variety in forms. In this photograph, a bowl, a jar, and a goblet show remnants of paint on their exteriors.

Sculpture in Mesopotamia

While the purposes that Mesopotamian sculpture served remained relatively unchanged for 2000 years, the methods of conveying those purposes varied greatly over time.

Learning Objectives

Identify the purposes of the sculptures featured in this concept

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Mesopotamian sculptures were predominantly created for religious and political purposes.

- Common materials included clay, metal, and stone fashioned into reliefs and sculptures in the round .

- The Uruk period marked a development of rich narrative imagery and increasing lifelikeness of human figures.

- Hieratic scale was often used in Mesopotamian sculpture to convey the significance of gods and royalty.

- After the end of the Uruk period, subject matter began to depict scenes of warfare and became increasingly violent and intimidating.

Key Terms

- register:A usually horizontal division of separate scenes in two- or three-dimensional art.

- hieratic scale:A visual method of marking the significance of a figure through its size. The more important a figure is, the larger it appears.

- terra cotta:Clay that has been fired in a kiln.

- high relief:A sculpture that projects significantly from its background, providing deep shadows.

- votive:An object left in temples or other religious locations for a variety of spiritual purposes.

- colossal:Extremely tall.

- lyre:A hand-held stringed instrument resembling a small harp.

- cylinder seal:A small object adorned with carved images of animals, writing, or both, used to sign official documents.

- in the round:Sculpture that stands freely, separate from a background.

- relief:A sculpture that projects from a background.

- mixed-media:Artwork consisting of two or more different materials.

- nomadic:Mobile; moving from one place to another, never settling in one location for too long.

The current archaeological record dates sculpture in Mesopotamia the tenth millennium BCE, before the dawn of civilization . Sculptural forms include humans, animals, and cylinder seals with cuneiform writing and imagery in the round or as reliefs. Materials range from terra cotta , stones like alabaster and gypsum, and metals like copper and bronze .

Hunter-Gatherers and Samarra

Because the artists of the hunter-gatherer era were nomadic , the sculptures they produced were small and lightweight. Even after cultures discovered agricultural methods, such as irrigation and animal domestication, artists continued to produce small sculptures. The seated female figure below (c. 6000 BCE), likely carved from a single stone, hails from the prehistoric Samarra culture (5500-4800 BCE). Like many prehistoric female figures, the features of this sculpture suggest that it was used in fertility rituals . Its breasts are accentuated, and its legs are spread in a position that might resemble a woman in labor. While the artist emphasized areas of the body related to reproduction, he or she did not add facial features or feet to the figure.

Uruk Period

Spirituality and communication are reflected in sculptures dating the Uruk period (4000-3100 BCE) of the late prehistoric era. Scholars believe that the gypsum Uruk trough was used as part of an offering to Inanna, the goddess of fertility, love, war, and wisdom. In addition to reliefs of animals, reliefs of reed bundles, sacred objects associated with Inanna, adorn the exterior of the trough. For these reasons, scholars do not believe the trough was used for agricultural purposes.

Animals, along with forms of writing, also appear on early cylinder seals, which were carved from stones and used to notarize documents. Officials or their scribes rolled the seals on wet clay tablets as a form of signature. Cylinder seals were also worn as jewelry and have been found along with precious metals and stones in the tombs of the elite members of society. The trough, cylinder seals, and various other sculptures of the Uruk period serve as examples of the rich narrative imagery that arose during this time.

The Uruk period also marked an evolution in the depiction of the human body, as seen in the Mask of Warka (c. 3000 BCE), named for the present-day Iraqi city in which it was discovered. This marble “mask” is all that remains of a mixed- media sculpture that also consisted of a wooden body, gold leaf “hair,” inlaid “eyes” and “eyebrows,” and jewelry. Like most sculptures produced during the time, the sculpture was originally painted in an attempt to make it look lifelike.

Early Dynastic Period

Sculpture built on older traditions and grew more complex during the Early Dynastic Period (2900-2350 BCE). Although artists still used clay and stone, copper became the dominant medium. Subject matter focused on spiritual matters, war, and social scenes.

A cylinder seal discovered in the royal tomb of Queen Puabi depicts two registers of a palace banquet scene punctuated by cuneiform script, marking a growing complexity in the imagery of this form of notarization. Each register features hieratic scale, in which the queen (upper register) and the king (lower register) are larger than their subjects.

Another sculpture of note is a mixed-media bull’s head that once adorned a ceremonial lyre found in Puabi’s tomb in Ur. The head consists of a gold “face,” lapis lazuli (a blue precious stone) “fur,” and shell “horns.” Although much of the lyre, whose dominant material was wood, disintegrated over time, contemporaneous imagery depicts lyres with similar decoration. Scholars believe that lyres were used in burial ceremonies and that the music that was played held religious significance.

Sculptures in human form were also used as votive offerings in temples. Among the best known are the Tell Asmar Hoard, a group of 12 sculptures in the round depicting worshipers, priests, and gods. Like the cylinder seal found in Queen Puabi’s tomb, the figures in the Tell Asmar Hoard show hieratic scale. Worshipers, as in the image below, stand with their arms in front of their chests and their hands in the position of holding offerings. Materials range from alabaster to limestone to gypsum, depending on each figure’s significance. One common feature is the large hollowed out eye sockets, which were once inlaid with stone to make them appear lifelike. The eyes held spiritual significance, especially that of the gods, which represented awesome otherworldly power.

Akkadian Empire

During the period of the Akkadian Empire (2271-2154 BCE), sculpture of the human form grew increasingly naturalistic, and its subject matter increasingly about politics and warfare.

A cast bronze portrait head believed to be that of King Sargon combines a naturalistic nose and mouth with stylized eyes, eyebrows, hair, and beard. Although the stylized features dominate the sculpture, the level of naturalism was unprecedented.

The Victory Stele of Naram Sin provides an example of the increasingly violent subject matter in Akkadian art, a result of the violent and oppressive climate of the empire. Here, the king is depicted as a divine figure, as signified by his horned helmet. In typical hieratic fashion, Naram Sin appears larger than his soldiers and his enemies. The king stands among dead or dying enemy soldiers as his own troops look on from a lower vantage point. The figures are depicted in high relief to amplify the dramatic significance of the scene. On the right hand side of the stele, cuneiform script provides narration.

Babylon and Assyria

The second millennium BCE marks the transition from the Middle Bronze Age to the Late Bronze Age . The most prominent cultures in the ancient Near East during this period were Babylonia and Assyria. Clay was the dominant medium during this time, but stone was also used. The most common surviving forms of second millennium BCE Mesopotamian art are cylinder seals, relatively small free-standing figures, and reliefs of various sizes. These included cheap plaques, both religious and otherwise, of molded pottery for private homes.

Babylonian culture somewhat preferred sculpture in the round to reliefs. Depictions of human figures were naturalistic. The Assyrians, on the other hand, developed a style of large and exquisitely detailed narrative reliefs in painted stone or alabaster. Intended for palaces, these reliefs depict royal activities such as battles or hunting. Predominance is given to animal forms, particularly horses and lions, which are represented in great detail. Human figures are static and rigid by comparison, but also minutely detailed. The Assyrians produced very little sculpture in the round with the exception of colossal guardian figures, usually lions and winged beasts, that flanked fortified royal gateways. While Assyrian artists were greatly influenced by the Babylonian style, a distinctly Assyrian artistic style began to emerge in Mesopotamia around 1500 BCE.

Architecture in Mesopotamia

Domestic and public architecture in Mesopotamian cultures differed in relative simplicity and complexity. As time passed, public architecture grew to monumental heights.

Learning Objectives

Differentiate how Mesopotamian cultures approached domestic and public architecture

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Mesopotamian cultures used a variety of building materials. While mud brick is the most common, stone also features as a structural and decorate element.

- The ziggurat marked a major architectural accomplishment for the Sumerians , as well as subsequent Mesopotamian cultures.

- Palaces and other public structures were often decorated with glaze or paint, stones, or reliefs .

- Animals and human-animal hybrids feature in the religions of Mesopotamian cultures and were often used as architectural decoration.

Key Terms

- alto relief:A sculpture with significant projection from its background.

- bas reliefs:Sculptures that minimally project from their backgrounds.

- public sphere:The world outside the home.

- ziggurat:A towering temple, similar to a stepped pyramid, that sat in the center of Mesopotamian city-states in honor to the local pantheon.

- private sphere:The home, or the domestic realm.

- load-bearing:A form of architecture in which the walls are the structure’s main source of support.

- stacking and piling:A form of load-bearing architecture in which the walls are thickest at the base and grow gradually thinner toward the top.

- pilaster:

A rectangular column that projects partially from the wall to which it is attached; it gives the appearance of a support, but is only for decoration.

The Mesopotamians regarded “the craft of building” as a divine gift taught to men by the gods, and architecture flourished in the region. A paucity of stone in the region made sun baked bricks and clay the building material of choice. Babylonian architecture featured pilasters and columns , as well as frescoes and enameled tiles. Assyrian architects were strongly influenced by the Babylonian style , but used stone as well as brick in their palaces, which were lined with sculptured and colored slabs of stone instead of being painted. Existing ruins point to load-bearing architecture as the dominant form of building. However, the invention of the round arch in the general area of Mesopotamia influenced the construction of structures like the Ishtar Gate in the sixth century BCE.

Domestic Architecture

Mesopotamian families were responsible for the construction of their own houses. While mud bricks and wooden doors comprised the dominant building materials, reeds were also used in construction. Because houses were load-bearing, doorways were often the only openings. Sumerian culture observed a rigid division between the public sphere and the private sphere , a norm that resulted in a lack of direct view from the street into the home. The sizes of individual houses varied, but the general design consisted of smaller rooms organized around a large central room. To provide a natural cooling effect, courtyards became a common feature in the Ubaid period and persist into the domestic architecture of present-day Iraq.

Ziggurats

One of the most remarkable achievements of Mesopotamian architecture was the development of the ziggurat, a massive structure taking the form of a terraced step pyramid of successively receding stories or levels, with a shrine or temple at the summit. Like pyramids, ziggurats were built by stacking and piling . Ziggurats were not places of worship for the general public. Rather, only priests or other authorized religious officials were allowed inside to tend to cult statues and make offerings . The first surviving ziggurats date to the Sumerian culture in the fourth millennium BCE, but they continued to be a popular architectural form in the late third and early second millennium BCE as well .

The image below is an artist’s reconstruction of how ziggurats might have looked in their heyday. Human figures appear to illustrate the massive scale of these structures. This impressive height and width would not have been possible without the use of ramps and pulleys.

Political Architecture

The exteriors of public structures like temples and palaces featured decorative elements such as bright paint, gold, leaf, and enameling. Some elements, such as colored stones and terra cotta panels, served a twofold purpose of decoration and structural support, which strengthened the buildings and delayed their deterioration.

Between the thirteenth and tenth centuries BCE, the Assyrians replaced sun-baked bricks with more durable stone and masonry. Colored stone and bas reliefs replaced paint as decoration. Art produced under the reigns of Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BCE), Sargon II (722-705 BCE), and Ashurbanipal (668-627 BCE) inform us that reliefs evolved from simple and vibrant to naturalistic and restrained over this time span.

From the Early Dynastic Period (2900-2350 BCE) to the Assyrian Empire (25th century-612 BCE), palaces grew in size and complexity. However, even early palaces were very large and ornately decorated to distinguish themselves from domestic architecture. Because palaces housed the royal family and everyone who attended to them, palaces were often arranged like small cities, with temples and sanctuaries , as well as locations to inter the dead. As with private homes, courtyards were important features of palaces for both utilitarian and ceremonial purposes.

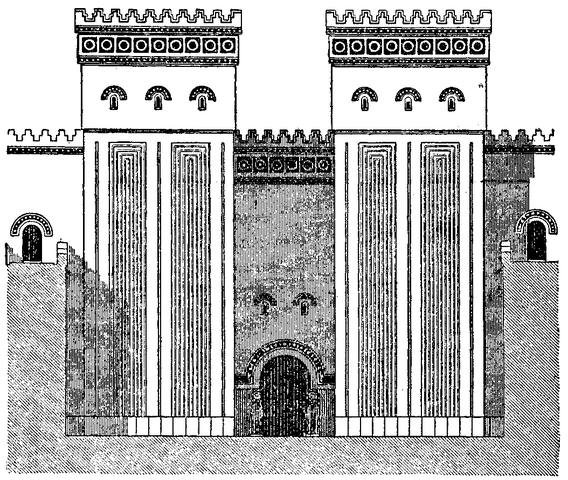

By the time of the Assyrian empire, palaces were decorated with narrative reliefs on the walls and outfitted with their own gates. The gates of the Palace of Dur-Sharrukin, occupied by Sargon II, featured monumental alto reliefs of a mythological guardian figure called a lamassu (also known as a shedu), which had the head of a human, the body of a bull or lion, and enormous wings. Lamassu figure in the visual art and literature from most of the ancient Mesopotamian world, going as far back as ancient Sumer (settled c. 5500 BCE) and standing guard at the palace of Persepolis (550-330 BCE).

Although the Romans often receive credit for the round arch, this structural system actually originated during ancient Mesopotamian times. Where typical load-bearing walls are not strong enough to have many windows or doorways, round arches absorb more pressure, allowing for larger openings and improved airflow. The reconstruction of Dur-Sharrukin shows that the round arch was being used as entryways by the eighth century BCE.

Perhaps the best known surviving example of a round arch is in the Ishtar Gate, which was part of the Processional Way in the city of Babylon. The gate, now in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, was lavishly decorated with lapis lazuli complemented by blue glazed brick. Elsewhere on the gate and its connecting walls were painted floral motifs and bas reliefs of animals that were sacred to Ishtar, the goddess of fertility and war.

The photograph above shows the immense scale of the gate. The photograph below shows the detail of a relief of a bull from the gate’s wall.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ubaid pottery.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ubaid_period#/media/File:Frieze-group-3-example1.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Cities of Sumer (en). Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Cities_of_Sumer_(en).svg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Uruk_Trough_-British_Museum.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31079210. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Stele of Vultures detail 01. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Stele_of_Vultures_detail_01.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Casting. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Casting. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Sumer. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Sumer. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Cuneiform. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Cuneiform. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- theocratic. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/theocratic. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Chalcolithic. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Chalcolithic. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Vase from the Late Ubaid Period. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ubaid_period#/media/File:Frieze-group-3-example1.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Old Babylonia Pottery. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Old_Babylonian_pottery_in_the_Oriental_Institute_Museum#/media/File:Old_Babylonian_pottery_-_Oriental_Institute_Museum,_University_of_Chicago_-_DSC07013.JPG. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Cuneiform texts from Ur III. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ur_III_administrative_texts_-_Oriental_Institute_Museum,_University_of_Chicago_-_DSC06995.JPG#/media/File:Ur_III_administrative_texts_-_Oriental_Institute_Museum,_University_of_Chicago_-_DSC06995.JPG. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Akkadian Pottery. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=40794666. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Ur III Pottery. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ur_III_pottery_-_Oriental_Institute_Museum,_University_of_Chicago_-_DSC06984.JPG#/media/File:Ur_III_pottery_-_Oriental_Institute_Museum,_University_of_Chicago_-_DSC06984.JPG. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Ubaid Period. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ubaid_period. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Art of Mesopotamia. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_of_Mesopotamia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Uruk Period. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Uruk_period. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ur III Cuneiform Tablets. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=40794957. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Babylonian Pottery. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=40809484. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Cuneiform. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Cuneiform_script#Akkadian_cuneiform. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ur III pottery. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=40794961. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Akkadian Pottery . Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=40794666. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Bull's_head_of_the_Queen's_lyre_from_Pu-abi's_grave. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Bull%27s_head_of_the_Queen%27s_lyre_from_Pu-abi%27s_grave_PG_800,_the_Royal_Cemetery_at_Ur,_Southern_Mesopotamia,_Iraq._The_British_Museum,_London..JPG. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Victory_stele_of_Naram_Sin_9066. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Victory_stele_of_Naram_Sin_9066.jpg#/media/File:Victory_stele_of_Naram_Sin_9066.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Burney reflief. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Burney_Relief#/media/File:British_Museum_Queen_of_the_Night.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Cylinder seal from tomb of Queen Pubai. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Flickr_-_Nic%27s_events_-_British_Museum_with_Cory_and_Mary,_6_Sep_2007_-_185.jpg#/media/File:Flickr_-_Nic%27s_events_-_British_Museum_with_Cory_and_Mary,_6_Sep_2007_-_185.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Sargon_of_Akkad. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sargon_of_Akkad.jpg#/media/File:Sargon_of_Akkad.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Uruk-period Cylinder Seal . Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Cylinder_seal_lions_Louvre_MNB1167.jpg#/media/File:Cylinder_seal_lions_Louvre_MNB1167.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Mask of Warka/Uruk Head. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:UrukHead.jpg#/media/File:UrukHead.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Votive of Male Worshiper from Tell Asmar. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Mesopotamia_male_worshiper_2750-2600_B.C.jpg#/media/File:Mesopotamia_male_worshiper_2750-2600_B.C.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Female Statuette from Samarra. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:FemaleStatuetteSamarra6000BCE.jpg#/media/File:FemaleStatuetteSamarra6000BCE.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Uruk Trough. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: upload.wikimedia.org/Wikipedia/commons/d/d8/Uruk_Trough_-British_Museum.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Samarra Culture. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Samarra_culture. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Tell Asmar Hoard. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Tell_Asmar_Hoard. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Inanna. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Inanna. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Art of Mesopotamia. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_of_Mesopotamia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Akkadian Empire. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Akkadian_Empire. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Cylinder Seal. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Cylinder_seal. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Uruk Trough. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Uruk_Trough?oldid=716721429. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Lyres of Ur. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Lyres_of_Ur. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Burney Relief. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Burney_Relief. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Choghazanbil2.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Chogha_Zanbil#/media/File:Choghazanbil2.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 542px-Lammasu.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Lamassu#/media/File:Lammasu.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 568px-Palace_of_Khorsabad.png. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Palace_of_Khorsabad.png. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- 320px-Ish-tar_Gate_detail.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ishtar_Gate#/media/File:Ish-tar_Gate_detail.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 32487-ziggurat-mesopotamia.jpg. Provided by: Wikispaces. Located at: mesopotamiadiv1.wikispaces.com/Architecture. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ishtar Gate. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ishtar_Gate_at_Berlin_Museum.jpg#/media/File:Ishtar_Gate_at_Berlin_Museum.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Ishtar Gate. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ishtar_Gate. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Sargon II. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Sargon_II. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Lamassu. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Lamassu. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Mesopotamia. Provided by: Wikispaces. Located at: mesopotamiadiv1.wikispaces.com/Architecture. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ashurbanipal. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashurbanipal. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ashurnasirpal II. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashurnasirpal_II. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Architecture of Mesopotamia. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Architecture_of_Mesopotamia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Assyria. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Assyria. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Early Dynastic Period (Mesopotamia). Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Early_Dynastic_Period_(Mesopotamia). License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Sumer. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Sumer. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Persepolis. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Persepolis. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike