Untitled Page 21

- Page ID

- 78692

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Chapter 10. Mapping, Re-Mediating, and Reflecting on Writing Process Realities: Transitioning from Print to Electronic Portfolios in First-Year Composition

Steven J. Corbett

Southern Connecticut State University

Michelle LaFrance

The University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth

Cara Giacomini

University of Washington

Janice Fournier

University of Washington

New technologies are often introduced to teachers and administrators in terms of their ideal use, and they are often disconnected from issues of context. Accounts of “best practices” in implementing technology can be similarly misleading. While such accounts might provide a sense of what can be done with the technology and the kinds of outcomes that can be achieved, best practices often fail to specify the conditions that contributed to success in a particular context, or to discuss what was involved in learning to use the technology successfully. We trace initial steps in the journey toward best practices, describing the “implementation path” for ePortfolios in first-year composition (FYC) courses at the University of Washington (UW).

Portfolios do more than move a writer’s work from paper to screen. In “Postmodernism, Palimpsest, and Portfolios: Theoretical Issues in the Representation of Student Work,” reprinted in this collection, Kathleen Blake Yancey claims that ePortfolios substantially “re-mediate” traditionally linear paper portfolio models. She suggests that, with collections like Situating Portfolios (1997) and New Directions in Portfolio Assessment (1994), compositionists have done a fair job of mapping the value of paper portfolios: their ability to highlight writing as a process and showcase student learning (Elbow, 1994; White, 1994; Yancey & Weiser, 1997, “Introduction”) and their usefulness in encouraging teacher formative versus summative evaluation (Belanoff & Dickson, 1991; Perry, 1997; Weiser, 1994 ). Indeed, leading authorities in composition have done much to chart the theoretical and practical terrain of paper portfolios. But, as Yancey asserts, “we are only beginning to chart the potential of the digital” (p. 757).

Composition scholars have begun to further link reflective practice to writing assessment, especially portfolio assessment (Peters & Robertson, 2007; Pitts & Ruggierillo, 2012; White, 1994, 2005; Yancey, 2004a, 2004b; Yancey & Weiser, 1997 ). In Teaching Literature as Reflective Practice, Yancey (2004b) highlights the insights she gained while transitioning from paper portfolios to ePortfolios. On a practical level, she found that grading ePortfolios took less time, for example; it was easier for her to click between links than scramble through printed pages (p. 81). Yancey’s biggest insight, however, from moving to ePortfolios involves student reflection. Drawing on John Dewey, Lev Vygotsky, and Donald Schön, Yancey maintains that reflection requires both scientific and spontaneous thinking, technical and nontechnical knowing, and is goal-directed, habitual, and learned (pp. 12-15). In “The Scoring of Writing Portfolios: Phase 2,” writing assessment expert Edward White believes the reflective letter is so important (and consequently so difficult for students to prepare) because “few of them are accustomed to thinking of their own written work as evidence of learning, or to taking responsibility for their own learning” (p. 591). Portfolios offer students exactly this opportunity for deeply purposeful and guided reflection. White argues further that reflection is also an important element in assessing student written work and their performances as evolving writers. White contends that two documents must accompany portfolio assessment of student work: first, a set of goals that outline the purposes of the particular course, program, or purpose of the collected works; and second, a reflective letter written by the student arguing how those goals may or may not have been met, using evidence from the portfolio (p. 586).

For proponents of portfolios, paper portfolios are indeed exercises in “deeply reflective activity,” but activity that can be “more singular than plural” (Yancey, 2004a, p. 91). ePortfolios, on the other hand, require students to reflect on their work from various angles, for multiple readers, and in multiple contexts. Students can use links and images like a gallery to link internally to their own work and externally to outside sources. In our two-year study of ePortfolio implementation at UW, our observations of the differences between paper portfolios and ePortfolios were similar to Yancey’s. We found that beginning to unlock the educational potential of these aspects of ePortfolios is reliant on incremental and interconnected changes in attitudes and practices among instructors and students.

Unfortunately, new technologies, such as ePortfolios, do not come with directions for how to create the environment that will support their most effective use (Lunsford, 2006). As suggested by Yancey, traditional conceptions of “composition” imply a linear organization of ideas presented on printed pages; ePortfolios, however, challenge instructors to expand on this notion and consider how visual rhetoric and design, and multiple navigational paths (afforded by hypertext) may also figure in the work of composing. Katerine Bielaczyc uses the term “implementation path” to describe the sequence of phases teachers move through as they progress from initial trials with a new technology to more sophisticated and effective use. Advancing along this trajectory, Bielaczyc argues, involves more than gaining familiarity with the functionality of a tool; it may also require shifting the mindset of students and teachers, engaging students and teachers in new types of learning activities, and moving toward new types of interactions among students and others outside of the classroom (p. 321). As research in the learning sciences has demonstrated, classrooms are complex learning environments where variables such as curriculum and instructional practices, cultural beliefs, social and physical infrastructure, and experience with technology all interact and influence how effectively technology is used (Brown & Campione, 1996; Collins, Joseph, & Bielaczyc, 2004). As Shepherd and Goggin (2012) suggest, reclaiming literacies in terms of new media infrastructures is critical. In the sections that follow, we highlight changes in the learning environment and classroom practice that emerged from our study as critical for advancing along the trajectory toward an effective implementation of ePortfolios.

Our Partnership

Supporting the use of instructional-technology on the UW campus, Learning & Scholarly Technologies (LST) develops and maintains the Catalyst Tool Kit, a suite of Web tools for use by faculty members, students, and staff, and conducts research on the use of technology for teaching and learning. Catalyst tools include Portfolio and Portfolio Project Builder; the former allows individuals to create portfolios and the latter allows instructors to create portfolio templates to help direct their students’ portfolios. As participants in the Inter/National Coalition for Electronic Portfolio Research (I/NCEPR), LST researchers have been collaborating with representatives from nine other colleges and universities since 2003 to study ePortfolio adoption. Our ongoing research on ePortfolios seeks to understand how students learn to compose in this medium—to select and reflect on artifacts, combine words and images in a coherent whole, effectively employ hypertext, and demonstrate awareness of audience and purpose. In autumn 2005, LST had the opportunity to enter a partnership with the Expository Writing Program (EWP) in the UW Department of English to better understand the effects of using ePortfolios in a specific context. During the 2005/06 academic year, LST researchers partnered with EWP to pilot the use of ePortfolios in nine sections of FYC. Participants in the pilot also agreed to take part in a study on the opportunities and challenges involved in ePortfolio adoption. The following academic year, 2006/07, EWP administrators gave all FYC TAs the choice of teaching with electronic or paper portfolios. In this essay, we share findings from our joint study of the ePortfolio pilot and second year of implementation. In the conclusion, we share observations on the current status of ePortfolio use within EWP.

The Setting

Several characteristics of EWP made it an ideal setting for adoption of ePortfolios. For one, the program had in place clearly articulated course outcomes and a well-developed paper portfolio assignment; administrators and instructors easily saw a fit between the Portfolio tool and the established curriculum. Although individual instructors determine the exact texts and assignments for each section of FYC, all students complete assignments designed to target four course learning outcomes. For the final portfolio, students are required to select 5-7 papers and develop a statement about how these works demonstrate achievement of the outcomes. In the traditional paper portfolio, students are asked to write their statement in the form of a cover letter to their instructor.

Other aspects of the program and classroom practice, however, posed challenges for our pilot. The first was how we could successfully train instructors on the functionality of the tool. Upwards of 30 sections of English 131 are offered each quarter, all of which are taught by teaching assistants. Nearly all of these TAs are in their first year of appointment; many have no prior teaching experience. Use of Catalyst Portfolio needed to be made as easy as possible for TAs already burdened with learning to teach, never mind teach with technology. More daunting challenges were posed by the department’s physical and social infrastructure. The majority of classrooms assigned to EWP courses, and many other courses in English, do not have technology available that would make the demonstration or discussion of ePortfolios easy. Exceptions to this pattern were courses in the department’s Computer-Integrated Courses (CIC) program, which has two computer classrooms dedicated to instructional use. Teaching in CIC is not an option for the majority of graduate students teaching FYC, however, since the program’s facilities serve a large population and have limited availability. Traditional practices and beliefs, as well as the physical infrastructure of English department classrooms, were challenges we anticipated might require a longer time frame to address.

Study Design

Participants

During the ePortfolio pilot in 2005/06, six TAs assigned to teach sections of FYC in fall, winter, and spring volunteered to participate in the study. Two of the six TAs were instructors in CIC. While all TAs expressed interest in implementing ePortfolios in their classes, they ranged widely in their knowledge of and comfort with educational technology. Two administrators from the English department also participated in the study, as did 48 students from the 12 sections of composition taught by TAs participating in the pilot study.

During the 2006/07 academic year, the EWP’s approach to implementing ePortfolios was two-fold: it gave all TAs teaching English 131 the option of teaching with ePortfolios and also began using ePortfolios in English 567, a required course on composition theory for TAs of 131. During the second year of our study (2006/07), 16 TAs, two instructors of 567, two program administrators, and 90 students participated in the study.

Study Procedures

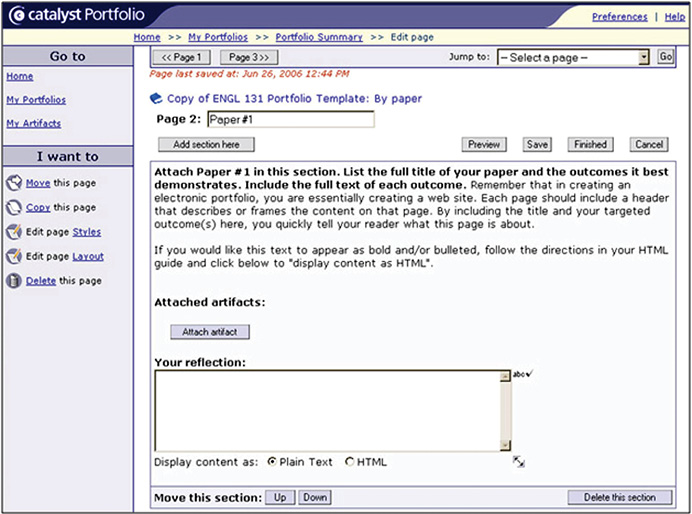

In autumn 2005, Catalyst researchers worked with the director and assistant director of EWP to create a project template, Portfolio Project Builder, which TAs could easily modify. The design closely matched the traditional paper portfolio in asking students to demonstrate achievement of the course outcomes, but distributed portions of the cover letter over several Web pages and enabled direct links to student documents. We created two ePortfolio templates—one in which pages were organized by outcomes, the other by papers—to match the organizational structure students most often used in their cover letters. Figure 1 shows a sample template page. The instructions and prompts disappear when students publish their portfolios, leaving only the students’ writing visible.

Figure 1: Section of an ePortfolio Template.

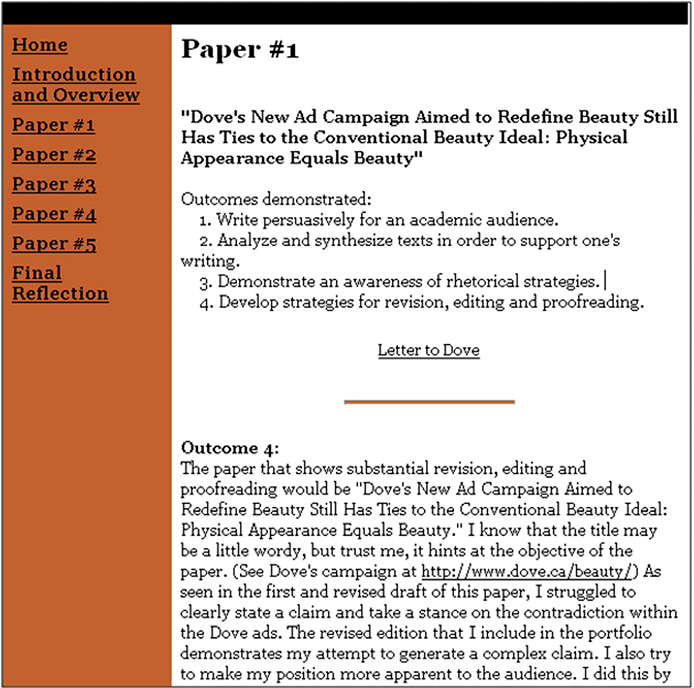

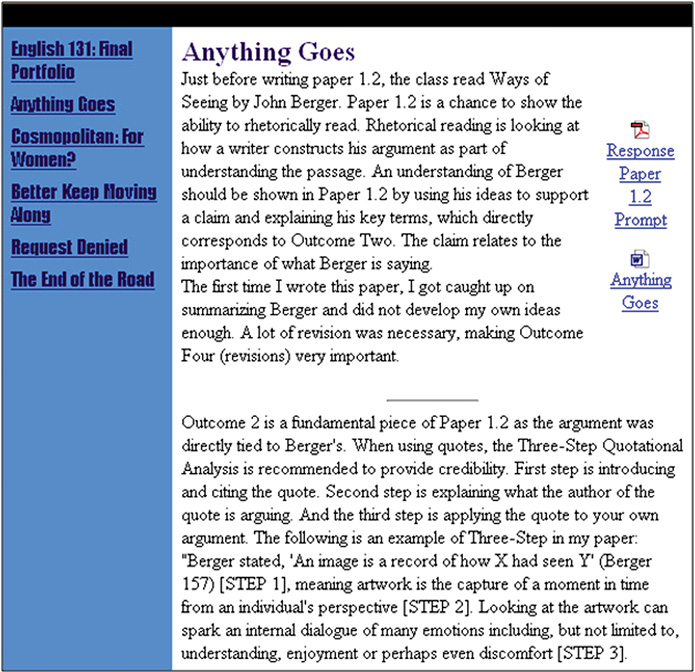

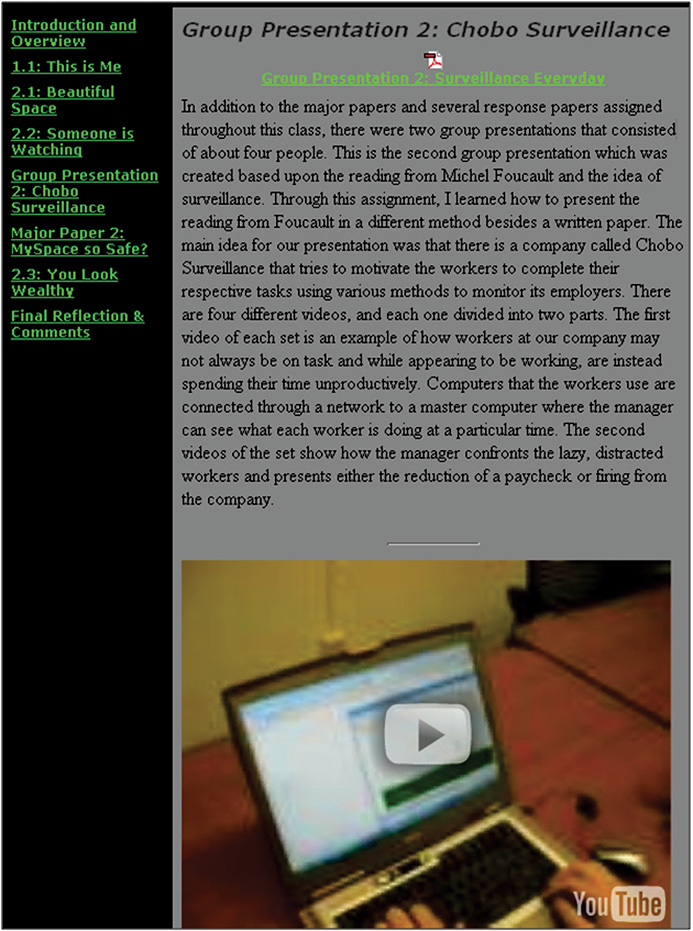

We also made two sample ePortfolios using these project templates; materials for these portfolios came from students who had taken FYC in the fall. Figure 2 shows a page from one of these sample portfolios initially created for the project. Figures 3 and 4 show pages from FYC students’ actual portfolios.

Figure 2: Page from a Sample Portfolio.

Figure 3: Excerpt from a FYC student’s ePortfolio.

Figure 4: Excerpt from a FYC Student’s ePortfolio, with Multimedia Elements.

At the start of winter 2006, we used the sample templates and ePortfolios as resources for participating TAs in a one-hour training session. We encouraged TAs to modify the project templates as they saw fit and to share the ePortfolio models with their students. They were also encouraged to make a model portfolio of their own, if possible. To control for effects of teaching the course a second time, 3 TAs taught with paper portfolios during winter quarter and 3 taught with ePortfolios; all 6 used ePortfolios in spring.

Data Collection

At the start of winter quarter 2006, all participating TAs in the pilot study completed a questionnaire about what challenges and opportunities they anticipated, for themselves and for their students, in the transition from paper to ePortfolios. At the end of winter and spring quarters, we interviewed TAs and asked them about their experiences using paper or ePortfolios and what they discovered (positive and negative) in this process. We also collected copies of each TA’s portfolio assignment and any support materials they distributed to their students. During the interviews, TAs shared three sample portfolios that represented a range of responses to their assignment.

Students in participating sections also completed a brief survey at the end of winter and spring quarters for the pilot study. The surveys asked students about their overall experience completing the paper portfolio (three sections in winter) or ePortfolio (three sections winter, six in Spring). At the start of winter quarter and again at the completion of the pilot, we interviewed two administrators from English about the challenges and opportunities they anticipated in a transition from paper to ePortfolios, and later what they had experienced or learned as a result of the study.

The following academic year, 2006-07, our data collection built upon the pilot and expanded to include more TAs and an additional class. The EWP gave the ePortfolio option to all of its TAs and included the design of an ePortfolio in the required composition theory class, English 567, so that all TAs teaching English 131 would have the experience of developing their own portfolios. At the end of autumn quarter, we interviewed two instructors of 567 about their experiences using ePortfolios and distributed an online survey to all TAs, inquiring into their experiences using ePortfolios, their teaching practices, and their plans and rationales for integrating or not integrating various technologies into classes. From this initial group of respondents, we selected seven TAs to for follow-up interviews later in the academic year. Consenting students in participating sections of English 131 received online surveys at the end of each quarter. These surveys asked students to comment on their overall experience completing electronic or paper-based portfolios. In all, 46 students in ePortfolio based courses and 44 students in paper-based portfolio courses responded to the online survey.

Findings

EWP administrators and TAs participating in the pilot study both considered the initial introduction of ePortfolios to be a success. Students in the nine sections (three in Winter, six in Spring) where ePortfolios were used completed their ePortfolios with only a few minor technical difficulties. In addition, all TAs reported that the quality of students’ ePortfolios equaled, and at times surpassed, the quality of paper portfolios that students had created during previous quarters. Several TAs observed that students who completed ePortfolios were better able to connect their writing with the course outcomes than students who completed paper portfolios. At the end of the pilot, administrators saw the potential for expanding this technology in EWP and eventually to other writing programs at the UW.

In the second year of our study, LST stepped back from its support role and the CIC program became the central technological support service for ePortfolio adoption in the classroom. The CIC program included resources such as templates and instructions on their website and provided assistance, at times on-to-one, to TAs who wanted to use ePortfolios and/or other technology in their classes. With the CIC program primed to provide technical support, the EWP took on the role of supporting the pedagogical applications of ePortfolios for new TAs. Despite greater departmental uptake and technological support within the department during the second year of our study, however, the number of TAs who adopted ePortfolios over paper-based portfolios was minimal. Overall, TAs in 2006/07 demonstrated a greater use of technology beyond ePortfolios compared with TAs in the 2005/06 pilot, but this trend was most apparent in CIC classes, where TAs attribute their usage of technology to the support and information they received from the CIC program. While, in general terms, the first leg of the journey toward the implementation of ePortfolios was traversed with ease, our research on the ePortfolio pilot identified four critical variables within the instructional context that affected, positively and/or negatively, the implementation of ePortfolios within particular course sections and had implications for long-term success of the project within the EWP. These include: portfolio assignment function, instructional practice, access to technology, and audience engagement. In the following section we discuss each variable in detail, providing insights from TAs and administrators and sharing our observations on various aspects of the research data.

Portfolio Assignment Function

Portfolio assignment function has two inter-related aspects: TAs’ understanding of the function of the portfolio assignment, paper or electronic, in the curriculum and their understanding of how the functionality of the Catalyst Portfolio tool reconfigures (“re-mediates” in Yancey’s terms) the standard paper portfolio. In our review of TAs’ portfolio assignments, we observed that TAs described a portfolio, whether paper or electronic, in the following ways: as a comprehensive collection of all course writing, as a vehicle for students to describe their journey as writers, and as a forum for persuasive argument.

The traditional paper portfolio used in EWP begins with a “cover letter” addressed to the instructor, in which the student introduces the contents of the portfolio and discusses them in relation to the course outcomes, followed by a comprehensive collection of all writing assignments, from revised papers to early paper drafts with instructors’ comments. The ePortfolio is not simply an electronic version of the cover letter. Instead, it takes the reflective writing traditionally done in the cover letter and distributes it across several pages of the portfolio. This distributed form of reflection allows students to discuss artifacts (papers, segments of papers, images, or other materials) at the point at which they are introduced. It also emphasizes the selection and organization of artifacts over the comprehensiveness of the collection. As Glenda Conway suggests, instructors should consider encouraging reflection throughout the quarter, rather than only at the end of a course with an all-inclusive cover letter. ePortfolios hold the potential for the realization of this sort of ongoing course reflection.

In general, during the 2005/06 pilot, we found that TAs who emphasized the portfolio as a comprehensive collection of all course work had the most difficulty transitioning from the paper to the electronic format. For instance, one TA, Amanda, felt strongly that the ePortfolio would not be complete without a distinct cover letter, in addition to the distributed reflections. Thus, she had students begin their ePortfolio with a page (or screen) containing the complete cover letter. They then copied various sections from this cover letter and distributed them throughout the pages where they introduced artifacts (papers, etc). Another TA, Ivy, felt strongly that all of her handwritten comments on early drafts of papers should be a part of the ePortfolio, so she asked her students to scan all comments. In both cases, the TAs’ desire for a comprehensive ePortfolio directly translated into more work for their students than would have occurred with the traditional paper portfolio model or using the ePortfolio templates without the addition of a separate cover letter or scanned comments. In interviews, both TAs indicated that their students expressed some resentment over the workload, although they were able to complete the assignment successfully. In contrast, TAs that emphasized students’ journeys as writers or students’ abilities to write persuasively about course outcomes adjusted more easily to the electronic format. Jenna was pleased that the ePortfolio allowed students to talk about individual artifacts more directly than the paper portfolio did:

The traditional portfolio (the paper one) is set up so it is all in the cover letter and you have got to make the matching yourself, which defeats the purpose for me, because it doesn’t highlight each artifact the way the ePortfolio does.

Cole described the difference between the paper and ePortfolio as follows: “Paper is a little more holistic and I think ePortfolios get specific.” Both Jenna and Cole felt students presented more compelling and detailed accounts of their progress with the ePortfolio than they had with paper portfolios. Adjusting assignments to play to the strengths of the ePortfolio represents a tangible step in the journey toward best practices, and one that can be taken with relative ease. Even TAs that initially struggled with this adjustment were able to identify the changes that would lead them to better practice in the future.

Instructional Practice

Achieving seamless integration between the ePortfolio and other course elements required flexibility in TAs’ instructional practice. In the final interview for the pilot study, Ivy, the TA who asked her students to scan all comments, observed, “I think it is impossible to just pretend [the ePortfolio] can be taught the same way as the paper portfolio.” Indeed, in year one all 6 TAs described various aspects of their instruction where they had made adjustments, or felt that they should have made adjustments, to integrate the ePortfolio into the curriculum. For instance, several TAs felt that the ePortfolio needed to be introduced early in the course, rather than at the end, so that any technical difficulties could be diagnosed and overcome with less time pressure. In addition, they acknowledged that this would allow students to have more opportunities to share their ePortfolios and learn from each other and the transition between the earlier paper assignments and the ePortfolio would be less abrupt. TAs also observed that the ePortfolio influenced the other assignments they designed for the course. Amanda explained: “I don’t think the ePortfolio should be the kind of thing that dominates the course, but the way you think about it can help shape the kind of assignments you create.” One TA intentionally designed a paper assignment with a visual component so students would have more visual elements to include in their ePortfolios.

TAs expressed that ePortfolios had a long-term potential to become vehicles for teaching students how to integrate text and images and for introducing multimedia elements into the course. In our review of students’ work we encountered a handful of visually sophisticated portfolios and a couple that experimented with multimedia, but these skills were not widely evident. In the final interview, one TA, Rob, shared his vision for the future of ePortfolios: “It becomes less of ‘this is an English paper’ and more of ‘this is an interdisciplinary project’ where students can bring in various media and bring in various resources.” Like portfolio assignment function, instructional practice is an area where individual initiative leads to a readily attainable course of action for the future.

Access to Technology

The six TAs participating in the pilot study had widely divergent access to technology in their classrooms. TwoTAs were a part of CIC, where they alternated their class sessions between a computer lab and a traditional classroom. Consistent access to tech-ready classrooms and basic hardware also continued to be problematic for TAs in the 2006/07 academic year. Other than CIC, the EWP does not have dedicated instructional space, so the classrooms assigned to TAs varied each quarter. As graduate student instructors, teaching small classes (20-22 students), in a department that does not have a strong reputation for technology use, most TAs typically were assigned small classrooms with very limited technology—no computer station, no data projector, and limited or non-existent Internet access. Regular access to a computer station and Internet in classrooms influences how fully ePortfolios can be integrated into all aspects of the course. While it is possible to use ePortfolios in non-technological classrooms, the lack of access limits the full realization of their potential, since TAs are not able to display ePortfolios for discussion or to walk students through the aspects of the ePortfolio creation process and students are not able to easily share their work during class sessions.

During the pilot and follow-up studies it was relatively simple for participating TAs, due to the small number of courses involved, to reserve a campus computer lab for one day during the quarter to show students ePortfolio models and orient them to Catalyst Portfolio. However, this solution loses viability as more sections of beginning composition use ePortfolios, since lab reservations are limited. While the CIC program does provide technology facilities, it does not have the capacity to accommodate all FYC TAs. Expanding the use of ePortfolios to a larger number of course sections will require taking steps to ensure TAs have adequate access to technology in classrooms. Making progress in this area will likely require action at the programmatic level, since instructor initiative will only overcome part of this challenge.

Audience Engagement

At the outset of the pilot study, both TAs and administrators felt that ePortfolios presented the opportunity for students to compose for a public audience. By the end of the pilot we observed that some progress had been made in this area; students’ writing in ePortfolios tended to address an audience beyond the instructor, unlike the cover letter in the traditional paper portfolio. Mary Perry maintains the importance of having students involved in the negotiation of audience with portfolios (also see Conway; Yancey Teaching Literature, “Postmodernism”). ePortfolios magnify this exigency. Some TAs, however, questioned the extent of audience engagement that was possible with the current use of ePortfolios. They observed that opportunities for students in their sections to share their ePortfolios with each other were limited. Introducing ePortfolios earlier in the quarter and access to better-equipped classrooms would facilitate the sharing of student work within a course section. Engaging an audience beyond an individual course section represents a larger challenge. As Amanda observed, “The writing might look really different if it were not being evaluated by their composition instructor.” By the end of the pilot, she felt an ideal ePortfolio would use less formal language that explained its contents in a manner that would engage an outside audience: “I mean it’s bizarre for the instructor to be requesting less formal language, but that is what I had to do with a few of my students.”

Publishing an ePortfolio online does not make it automatically “public.” Building an authentic external audience requires a substantial effort from TAs, program administrators, and LST or other technology support units. Facilitating the sharing of ePortfolios between students in the EWP program would be a useful next step toward expanding audience engagement. Enabling such an exchange would likely require a technical solution for collecting, sharing, and sorting students’ ePortfolios, along with changes in program curriculum to encourage interaction between courses. At the end of the second year of the study, we observed that building an audience beyond the program constitutes an even larger challenge. This leg of the ePortfolio implementation path covers difficult terrain, since making this journey requires a cultural shift toward increased connection between EWP and other individuals and units at the UW and beyond the institution.

Implications for EWP

The work of Bielaczyc, Yancey, and others foreground the idea that the implementation of new pedagogical technologies requires students and teachers to adjust their attitudes and practices. These sorts of adjustments of mind and action were clearly seen during the first-year pilot among participating instructors. A year later, additional adjustments are evident on a wider scale as EWP continues its implementation of ePortfolios. All TAs who taught with ePortfolios reported that they improved each quarter in understanding their own expectations for the ePortfolio and communicating these to their students (particularly in terms of visual design), and all found that showing examples of other ePortfolios to their students was critical to their student’s success.

In year two, the EWP and the English department as a whole took greater role in promoting ePortfolios in the program. Although use of ePortfolios was not yet a requirement, all FYC instructors new in 2006-07 were offered the option of teaching with ePortfolios or the standard paper model in their sections. In addition, all new TAs in EWP gained personal experience with Catalyst Portfolio during their first quarter. The director of EWP and a fellow professor agreed to teach with ePortfolios in the required composition theory course, asking each TA to construct a teaching portfolio using the Catalyst portfolio tools. TAs and professors underwent the same negotiations of attitude and practice that students and TAs experienced in the classroom during the pilot study. In this context, however, professors were able to expand on the “lifelong learning” benefits of portfolios (see Chen, 2009 and the conclusion below), emphasizing to TAs their value as tools for reflection and for self-promotion on the job market (Heinrich, Bhattacharya, & Rayudu, 2007). Both professors confessed minimal experience teaching with technology at the start. One commented: “Like most faculty in the department, I haven’t used much technology. I never developed expertise with it. Until I taught with ePortfolios in 567, I never used ePortfolios, listservs, or Web sites for my courses.” Both professors came away at the end of the quarter delighted with the results of their experiment and enthusiastic about promoting more systematic ePortfolio use next year.

Additional structures within the department—formal and informal—also helped to advance best practices with ePortfolios. LST and EWP together conducted only one information session early in the year to discuss technical and pedagogical strategies associated with successful integration of the technology. Later discussion of “best practices” happened informally, as TAs in shared offices talked about their experiences and innovative assignments using ePortfolios. Extending beyond the program, the implementation of ePortfolios in the curriculum was also a topic of Practical Pedagogy roundtables hosted by the Department of English.

Further change was evident in the department’s computer classrooms. The CIC program became directly involved in the implementation of ePortfolios in all 100- and 200-level English courses, housing the easily navigable ePortfolio guidelines and templates on their Web page and providing substantial support to any instructors wishing to use ePortfolios (http://depts.washington.edu/engl/cic/portfolio_final.php). In CIC’s quarterly training seminars, the CIC director and assistants introduced instructors who are often new to teaching with technology to the potential educational benefits of multiple tools, including ePortfolios. The close connection between ePortfolios and other Catalyst tools (i.e., online discussion, homework collection, and file sharing) becomes clear to new instructors as they witness the compatibility between various computer technologies that may be used inside or outside of the classroom to enhance student learning. TAs teaching with ePortfolios felt that EWP and the larger English department should embrace multiple educational technologies, because students were already using them or would need to learn them. One TA even expressed the belief that use of technology should be incorporated into the outcomes for English 131 more broadly. With CIC promoting their use, ePortfolios are extending to courses beyond FYC and being more tightly integrated with other technologies; several CIC instructors over this last year have expressed enthusiasm about “going paperless” in their classes. More sophisticated uses of ePortfolios (for example, students creating their own portfolios without the help of a template) may also be possible and appropriate in intermediate or advanced writing classes.

Some TAs in the study did report that “TA resistance” was the main obstacle to more widespread adoption of ePortfolios—a moniker that described a number of affective responses, including discomfort with technology, a sense that workload might increase, and uncertainty about the pedagogical ends of the electronic format. At the end of our two-year study we anticipated that the English department would continue to advance on a trajectory of more effective and sophisticated use of ePortfolios, with teaching assistants and CIC playing a major role in their implementation.

Mapping Student and TA Experience

We turn now to discussing in more depth the experience of students and TAs who used ePortfolios in their classes. In the second year of this study, we collected paper and electronic portfolios from consenting students in participating sections of English 131. From these portfolios we chose a random sample of 12 paper portfolios and 12 ePortfolios to analyze on several dimensions: the intended audience for the portfolio, degree and type of evidence used to support claims, visual organization of information, total word count for commentary, and use of multimedia artifacts. We also asked TAs to share with us student portfolios that represented a range of responses to their assignments.

Our initial findings demonstrate differences between the ways students approach paper versus electronic portfolios. When using paper portfolios, students tended to address the instructor as the primary audience for their work. In general, however, those students who created ePortfolios addressed an audience beyond the classroom, while at the same time assuming that audience had knowledge of the EWP and the UW. Portfolio format seemed to have little effect on students’ abilities to use evidence in support of a claim, but those who created ePortfolios tended to include direct references to or excerpts from their work more often than those who created paper portfolios. Students who used paper portfolios used the cover letter to organize and present information about the work that followed, but students who created electronic portfolios used visual cues to organize their work via headings, fonts, colors and bullets. Students using ePortfolios did vary widely in the extent to which they used particular visual cues to make their portfolios more readable. Although the electronic environment allows for inclusion of a greater array of artifacts than the paper portfolio, only five of 12 ePortfolios reviewed included linked or embedded multi-media artifacts. Images were included in each portfolio, but they were not explicitly referenced or discussed. Finally, our data shows that students who completed ePortfolios wrote almost twice as much in their reflections overall than for students who completed paper portfolios (see Table 1).

Table 1: Total Word Count for Two Portions of Electronic and Paper Portfolios

|

Overall Reflection |

||

|

Average |

Range |

|

|

ePortfolio |

3341 |

1458-5226 |

|

Paper Portfolio |

1714 |

1139-2652 |

Overall, the student ePortfolios shared in the second year of the study were not just longer, but clearly more sophisticated than those shared by TAs during the pilot year. Several students, on their own initiative, chose to use a theme to connect the various elements of their ePortfolios (i.e. one student compared her growth as a writer to musical composition and used language and images connected to music throughout her ePortfolio). By Spring quarter, some TAs reported that they encouraged students to use themes. The range in design strategies and total words in both portfolio formats are likely the result of different instructions and/or templates provided by TAs.

Online survey responses demonstrated further differences of perception among students creating paper portfolios and those using ePortfolios. Students who completed the paper portfolios tended to interpret the survey as asking about the effects of the portfolio process on their learning. Those who completed ePortfolios interpreted the survey as asking them about the technology. Students who created paper portfolios indicated at higher rates that they had “benefited” from the portfolio process, attributing all positive experiences to the acts of reflection, receiving feedback, and working on a revision cycle in and of themselves, while students who created ePortfolios frequently wrote about the benefits or drawbacks of the portfolio software.

At the same time, students overwhelmingly recommended the ePortfolio format that they had used for future courses, with 65.2% of students endorsing the ePortfolio format and only 50% endorsing the paper format. TAs teaching with ePortfolios also tended to express high levels of enthusiasm for the ePortfolios their students created. However, these TAs also expressed confusion over the relationship of some elements of the ePortfolios to students’ grades. For instance, TAs reported telling students that the visual elements of the ePortfolio would have little or no effect on grades, unless students made poor design choices that made the portfolio difficult to read. TAs expressed some further uncertainty about whether or not this was the correct choice, since in the end they preferred the ePortfolios that incorporated visual elements. Interestingly, the most visually sophisticated assignment encountered during the study—a project that asked students to integrate visual and textual materials—was created by a TA using the paper portfolio format.

Conclusion

While recognizing the pedagogical implications of tools that enable student reflection, Ed White also advises practitioners to provide explicit instruction to students in how to negotiate the reflective letter as a rhetorical, persuasive document or argument. He writes: “without instruction, students are likely to give a hasty overview of the portfolio contents, including much personal experience about the difficulty of writing and revising—along with some fulsome praise of the teacher—without attending to the goals of the program at all” (p. 591). White urges direct, focused instruction in how and why to compose the portfolio cover letter so that students will be more likely to see how they met the goals and expectations of the course and how they did or not apply themselves with full effort and engagement in their learning. Our findings demonstrate that new instructors need similar support for understanding the applications of portfolio tools and their usefulness in encouraging student reflection in their classrooms. Simply having an electronic portfolio tool available to instructors does not mean that tool will be widely adopted or used efficaciously. Like students, new instructors benefit from being shown and supported in the effective use of tools that enable non-traditional forms of student learning, reflection, and movement toward course learning objectives.

In the years following our data collection, progress continues to be made toward more closely integrating the support and services available to TAs teaching portfolio-based classes in the EWP. Working closely with the CIC, the EWP has set out to introduce TAs to the ePortfolio option earlier in their orientation process and has worked to increase the availability of sample assignments and examples of student-designed projects for TAs to adopt and adapt. To alleviate the techno-anxieties of new TAs, the CIC program has not only continued to provide one-to-one support services for TAs using ePortfolios in their classrooms, but also increased its availability for classroom visits to all TAs using the ePortfolio option. CIC program staff have also developed a website specifically tailored to answering student questions and can be available in person when necessary. The result of these efforts is that TAs now no longer bear sole or full responsibility for teaching their students how to use or design with the tool. Most importantly, practices within the EWP are changing: the ePortfolio has been made the default mode for new TAs in the program and the ePortfolio is no longer described as an optional alternative to paper portfolios in program documents or support materials. In fact, the online version of the portfolio tool is no longer differentiated as an “ePortfolio” at all, but is referred to as simply the “portfolio.” These recent moves on the programmatic level encourage all involved in planning and support for new TAs—as time advances, ePortfolios are becoming a more familiar pedagogical fixture of teaching in the EWP.

On a final note, during the academic year 2008/09, LST informed the EWP that Catalyst Portfolio and Portfolio Project Builder, the current tools available for ePortfolios, were going to be phased out of use at the UW by the end of the 2009/10 academic year, due to the advanced age of the software. Discussion is currently underway on whether LST will build a new portfolio tool or will encourage adoption of a commercial or open-source solution. This change initially created anxiety among administrators of the EWP and CIC, as much time and energy had been devoted to developing resources for TAs who chose to use ePortfolios in their classrooms. A new tool will require that all resources available to TAs (directions and guidelines for classroom use, troubleshooting tips, and examples of students’ portfolios) be redesigned. At the time of submission of this article, an EWP/CIC working group (in coordination with LST) has been set up to investigate options for moving forward. This reaction is heartening. Instead of simply abandoning ePortfolios, the EWP has committed to having electronic options available to those TAs who would chose to include technological tools for reflection in their classes. This change in the educational software and technology availability, however, has prevented EWP/CIC from making ePortfolios mandatory at this time. But even without required use, ePortfolio implementation is continuing to advance in the program.

While visualizing ideal use provides inspiration and commitment to the development of support for new technologies, analyzing the journey of technology implementation increases our practical understanding of educational change. On the one hand, our study reveals the early stages of a journey that may eventually lead to more extensive and well-supported ePortfolio use within the institution. On the other hand, it emphasizes the everyday challenges of ePortfolio adoption, rather than the ideal outcome. Our research highlights subtle shifts in practice and culture that could over time—with further on-going support and more purposeful recruitment and training of new instructors—culminate in dramatic transformations.

Other individuals and/or institutions that are embarking on the implementation journey need to remember that true transformation takes time. Unlocking the full potential of new technology, such as ePortfolios, requires a series of changes, many of which will not be obvious until the technology has been introduced. For EWP, our study of the ePortfolio pilot made visible early changes in practice and identified areas where shifts will need to be made as the journey continues. One valuable aspect of our research study was that it provided an opportunity for those participating in the ePortfolio pilot to reflect on their experiences and partnerships. More importantly, we provided a means of communicating the lessons from that reflection. Brad Peters and Julie Robertson, reflecting on their analyses of WAC portfolio partnerships, believe that portfolio learning can be “a social force that also gives rise to a faculty “culture of assessment,’ where reflection becomes the dominant mode of uniting faculty practice and theory” (p. 208). Venues for reflection and communication are important components of any technology implementation, since the experiences and ideas of early participants can help shape and unify future steps in the process. Other individuals or institutions may not follow the same path that we traced in this paper, but this case identifies variables, both pros and cons, to consider as they chart their own progress with ePortfolios.

Within the ePortfolio community it is important to recognize the incremental stages of transformation, in addition to focusing on the long-term goals for this technology. While ePortfolios do have the potential to promote lifelong learning and reflection, making this future viable will require an extended series of subtle transformations in instructional practice and departmental and institutional culture, as well as expanding awareness and collaboration within social and professional spheres.

References

Belanoff, P., & Dickson, M. (Eds.). (1991). Portfolios: Process and product. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook.

Bielaczyc, K. (2006). Designing social infrastructure: Critical issues in creating learning environments with technology. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 15(1), 301-329.

Black, L., Daiker, D. A., Stygall, G., & Sommers, J. (Eds.). (1994). New directions in portfolio assessment: Reflective practice, critical theory, and large-scale scoring. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook.

Brown, A. L., & Campione, J. C. (1996). Psychological theory and the design of innovative learning environments: On procedures, principles, and systems. In L. Schauble, & R. Glaser (Eds.), Innovations in learning: New environments for education (pp. 289-325). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Chen, H. L. (2009). Using eportfolios to support lifelong and lifewide learning. In D. Cambridge, B. Cambridge, & K. B. Yancey (Eds.), Electronic portfolios 2.0: Emergent research on implementation and impact (pp. 29-35). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Collins, A., Joseph, D., & Bielaczyc, K. (2004). Design research: Theoretical and methodological issues. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 13(1), 15-42.

Conway, G. (1994). Portfolio cover letters, students’ self-presentation, and teachers’ ethics. In L. Black et al. New directions in portfolio assessment: Reflective practice, critical theory, and large-scale scoring (pp. 83-92). Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook.

Elbow, P. (1994). Will the virtues of portfolios blind us to their potential dangers? In L. Black et al. (Eds.), New directions in portfolio assessment: Reflective practice, critical theory, and large-scale scoring (pp. 40-55). Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook.

Greenberg, G. (2004). The digital convergence: Extending the portfolio model. Educause Review, 39(4), 28-37.

Heinrich, E., Bhattacharya, M., & Rayudu, R. (2007). Preparation for lifelong learning using ePortfolios. European Journal of Engineering Education, 32(6), 653-663.

LaCour, S. (2005). The future of integration, personalization, and ePortfolio technologies. Innovate Online, 1(4). Retrieved from http://www.innovateonline.info/pdf/vol1_issue4/The_Future_of_Integration,_Personalization,_and_ePortfolio_Technologies.pdf

Lunsford, A. (2006). Writing, technologies, and the fifth canon. Computers and composition, 23(2), 169-177.

Perry, M. (1997). Producing purposeful portfolios. In K. B. Yancey, & I. Weiser (Eds.), Situating portfolios: Four perspectives (pp. 182-195). Logan, UT: Utah State University Press.

Peters, B., & Robertson, J. F. (2007). Portfolio partnerships between faculty and WAC:

Lessons from disciplinary practice, reflection, and transformation. College Composition and Communication, 59(2), 206-236.

Pitts, W. & Ruggierillo, R. (2012). Using the e-portfolio to document and evaluate growth in reflective practice: The development and application of a conceptual framework. International Journal of ePortfolio. 1(1), 49-74.

Schofield, J. (1997). Computers and social processes: A review of the literature. Social Science Computer Review, 15, 27-39.

Shepherd, R., & Goggin, P. (2012). Reclaiming “old” literacies in the new literacy information age: The functional literacies of the mediated workstation. Composition Studies, 40(2), 66-91.

Weiser, I. (1994). Portfolios and the new teacher of writing. In L. Black et al. (Eds.), New directions in portfolio assessment: Reflective practice, critical theory, and large-scale scoring (pp. 219-229). Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook.

Wheeler, B. (2004). The open source parade. Educause Review, 39(5), 68-69.

White, E. M. (1994). Portfolios as an assessment concept. In L. Black et al. (Eds.), New directions in portfolio assessment: Reflective practice, critical theory, and large-scale scoring (pp. 25-39). Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook.

White, E. M. (2005). The scoring of writing portfolios: Phase 2. College Composition and Communication, 56(4), 581-600.

Yancey, K. B. (1997). Situating portfolios: Four perspectives (pp. 1-17). Logan, UT: Utah State University Press.

Yancey, K. B. (2004a). Postmodernism, palimpsest, and portfolios: Theoretical issues in the representation of student work. College Composition and Communication, 55(4), 738-762.

Yancey, K. B. (2004b). Teaching literature as reflective practice. Urbana, IL: NCTE.

Yancey, K. B., & Weiser, I. (1997). Situating portfolios: An introduction. In K. B. Yancey, & I. Weiser (Eds.), Situating portfolios: Four perspectives (pp. 1-20). Logan, UT: Utah State University Press.