8: Untitled Page 04

- Page ID

- 19009

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)I knew she was but as a withering flour,

That’s here to day perhaps gone in an hour;

Like as a bubble, or the brittle glass,

Or like a shadow turning as it was.

More fool then I to look on that was lent,

As if mine own, when thus impermanent.

Farewel dear child, thou ne re shall come to me,

But yet a while and I shall go to thee.

Mean time my throbbing heart’s chear’d up with this

Thou with thy Saviour art in endless bliss.

2.7.8 “On My Dear Grandchild Simon Bradstreet”

No sooner come, but gone, and fal’n asleep,

Acquaintance short, yet parting caus’d us weep.

Three flours, two scarcely blown, the last i’th’ bud,

Cropt by th’ Almighties hand; yet is he good,

With dreadful awe before him let’s be mute,

Such was his will, but why, let’s not dispute,

With humble hearts and mouths put in the dust,

Let’s say he’s merciful as well as just.

He will return, and make up all our losses,

And smile again, after our bitter crosses.

Go pretty babe go rest with Sisters twain

Among the blest in endless joyes remain.

2.7.9 Reading and Review Questions

1. In “The Prologue,” what are her “inherent defects” to which Bradstreet brings attention? Why does she do so? Does the poem as a whole bear out these “defects” as actual defects? To what degree, if any, do these defects reflect Bradstreet’s sense of her gender and her religion?

2. Why do you think Bradstreet essentially records her knowledge of literature and the classics in “The Prologue?”

3. In “The Author to Her Book,” what conventional maternal behaviors does Bradstreet apply to her book? Why? Why does she make an especial note of her “offspring” not having a father?

Page | 183

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

4. In “To My Dear and Loving Husband,” what conventions and tropes often used in the sonnet form does Bradstreet use? What, if anything, is unconventional in her using them? Why?

5. How does Bradstreet console herself for such losses and suffering as the deaths of her grandchildren and the burning of her house? How, if at all, does her religious faith support her as a woman?

2.8 MICHAEL WIGGLESWORTH

(1631–1705)

Michael Wigglesworth’s parents, Edward

and Esther Wigglesworth, brought him with

them when they emigrated to the American

colonies in 1683. Wigglesworth was educated

in America, first at home under the tutelage

of Ezekiel Cheever (1514–1708), then at

Harvard. In 1652, he earned his MA from

Harvard and remained there as lecturer.

After his graduation, Wigglesworth also

began preaching; he ultimately became an

ordained minister at Malden, Massachusetts

in 1656. Chronic illness curtailed his ministry

activities, ministry that he nevertheless

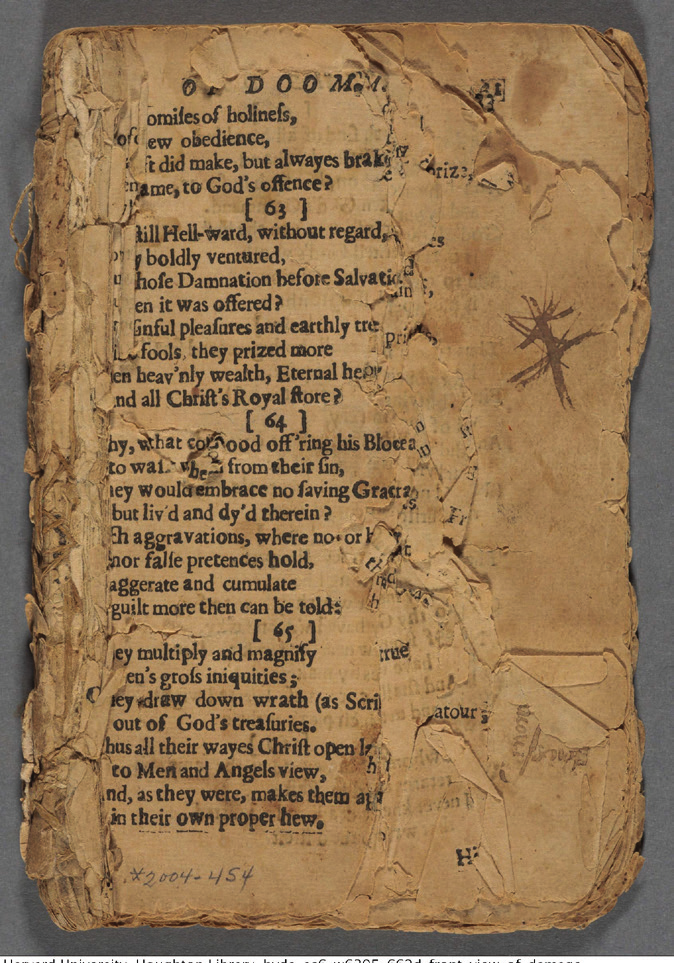

maintained through his writing. His The

Day of Doom: Or, A Description of the Great

and Last Judgment, with a Short Discourse

about Eternity (1662) is a didactic religious

poem, exhorting his parishioners to adhere Image 2.4 | First Edition of The Day

of Doom

to true Puritan doctrines and ideals. Its Author | Michael Wigglesworth publication coincided with the controversy Source | Wikimedia Commons over church membership, later resolved in License | Public Domain what became known as the Half-Way Covenant, allowing church membership without conversion testimony. The Covenant intended to bring colonists to the fervid faith held by first-generation settlers. This historical context may help explain the purpose of Wigglesworth’s work.

Its effectiveness as a didactic piece appears in its extraordinary popularity (selling over 1,800 copies) and its being used to teach children Puritan theology.

Its 224 eight-line stanzas—all with striking details and often terrifying images—

arrest the attention of wandering minds and souls threatening to fall into sins of omission and commission, souls that may repent too late before the inevitable judgment day. Its stanzaic lines alternate between eight and six syllables; with internal rhymes in the eight-syllable lines, and end rhymes in alternating pairs Page | 184

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

of the six-syllable lines. Through its artistry and style combined with substance, through its sweetness and light, The Day of Doom fulfills poetry’s highest purpose (according to Sir Phillip Sidney) in encouraging right living.

2.8.1 The Day of Doom

Or, A Description of the Great and Last Judgment

(1662)

I

Still was the night, serene and bright,

when all men sleeping lay;

Calm was the season, & car [. . .] l reason

thought so ‘twould last [. . .] or ay.

Soul take thine ease, let sorrow cease,

much good thou hast in store;

This was their song their cups among

the evening before.

II

Wallowing in all kind of sin,

vile wretches lay secure,

The best of men had scarcely then

their Lamps kept in good ure.

Virgins unwise, who through disguise

amongst the best were number’d,

Had clos’d their eyes; yea, and the Wise

through sloth and frailty slumber’d.

III

Like as of old, when men grew bold

Gods threatnings to contemn,

(Who stopt their ear, and would not hear

when mercy warned them?

But took their course, without remorse,

till God began to pour

Destruction the world upon,

in a tempestuous show [. . .]

IV

They put away the evil day

and drown’d their cares and fears,

Till drown’d were they, and swept away

by vengeance unawares:

Page | 185

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

So at the last, whilest men sleep fast

in their security,

Surpriz’d they are in such a snare

as cometh suddenly.

V

For at midnight broke forth a light,

which turn’d the night to day:

And speedily an hideous cry

did all the world dismay.

Sinners awake, their hearts do ake,

trembling their loyns surprizeth;

Am [. . .] z’d with fear, by what they hear,

each one of them ariseth.

VI

They rush from beds with giddy heads,

and to their windows run,

Viewing this Light, which shines more bright

than doth the noon-day Sun.

Straightway appears (they see’t with [. . .] ears)

the Son of God most dread,

Who with his train comes on amain

to judge both Quick and Dead.

VII

Before his face the Heavens give place,

and Skies are rent asunder,

With mighty voice and hideous noise,

more terrible then Thunder.

His brightness damps Heav’ns glorious l [. . .] mps,

and makes them hide their heads:

As if afraid, and quite dismaid,

they quit their won [. . .] ed steads.

VIII

Ye sons of men that durst contemn

the threatnings of Gods word,

How cheer you now? your hearts (I trow)

are thrill’d as with a sword.

Now Atheist blind, whose bru [. . .] ish min [. . .]

a God could never see,

Page | 186

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

Dost thou perceive, dost now believe

that Christ thy Judge shall be [. . .]

IX

Stout courages (whose hardiness

could death and hell out-face)

Are you as bold now you behold

your Judge draw near apace?

They cry, No, no: alas and wo [. . .]

our courage all is gone:

Our hardiness, ( [. . .]ool-hardiness)

hath us undone, undone.

X

No heart so b [. . .]ld but now grows cold,

and almost dead with fear:

No eye so dry but now can cry,

and pour out many a tear.

Earths Po [. . .] entates and pow’rful States,

Captains and men of Might

Are qui [. . .] e abasht, their courage dasht.

At this most dreadful sight.

XI

Mean men lament, great men do r [. . .] nt

their robes and tear their hair:

They do not spare their flesh to tear

through horrible despair.

All kindreds wail, their hearts do fail:

horrour the world doth fill

Wi [. . .] weeping eyes, and loud out-cries,

yet knows not how to kill.

XII

Some hide themselves in Caves and Delves,

and pl [. . .] ces under ground:

Some rashly leap into the deep,

to, scape by being drown’d:

Some to the Rocks, (O sensless blocks)

and woody Mountains run,

T [. . .] a [. . .] there they might this fearful [. . .] ight and dreaded Presence shun.

Page | 187

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

XIII

In v [. . .] in do they to Mountains say,

Fall on us, and us hide

From Judges i [. . .] e, more hot then fire,

For who may it abide?

No hiding place can from his face

sinners at all conceal,

Whose flaming eye hid things doth spy,

and darkest things reveal.

XIV

The Judge draws nigh, exalted high

upon a lofty Throne,

Amids the throng of Angels strong,

LIKE Israel’s [. . .] oly One.

The excellence of whose Presence,

and awful Majesty,

Am [. . .] zeth Nature, and every Crea [. . .] ure

doth more then terrifie.

XV

The Mountains smo [. . .] k, the Hills are shook,

the Earth is rent and torn,

As if she should be clean dissolv’d,

or from her Cen [. . .] re born.

The Sea doth roar, forsakes the sho [. . .] e,

and shrinks away for fear:

The wild beasts flee into the Sea

so soon as he draws nea [. . .].

XVI

Whose glory bright, whose wond [. . .] ous might,

whose Power Imperial,

So far surpass what ever was

in Realms Terrestrial;

That tongues of men (nor Angels pen)

cannot the same express:

And the [. . .] efore I must pass it by,

lest speaking should transgress.

XVII

Before his throne a Trump is blown,

proclaiming th’ day of Doom:

Page | 188

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

Forthwith he c [. . .] ies, Ye dead arise,

and unto Judgement come.

No sooner said, but ‘tis obey’d;

Sepulch [. . .] es open’d are;

Dead bodies all [. . .] ise at his call,

and’s mig [. . .] y power declare.

XVIII

Both s [. . .] a and land at his command,

their dead at once surrender:

The fire and air constrained are

also [. . .] heir de [. . .] d to [. . .] ender.

The mighty wo [. . .] d of [. . .] his great Lord

links body and soul toge [. . .] her,

Both of the just and the unjust,

to part no more for ever.

XIX

The same translates from mortal states

[. . .] o imm [. . .] tality,

All that survive, and be alive,

i’th’ twinkling of an eye.

That so they may abide for ay

to endless weal or woe;

Both the Renate and Reprobate

are made to dye no moe.

XX

His winged Hosts fly through all Coasts,

together gathering

Both good and bad, both quick and dead,

and all to Judgement bring.

Out of their holes these creeping Moles,

that hid themselves for fear,

By force they take, and quickly make

before the Judge appear.

XXI

Thus every one before the Throne

of Christ the Judge is brought,

Both righteous and impious,

that good or ill had wrought.

A sepa [. . .] ation, and diff’ring station

Page | 189

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

by Christ appointed is

To sinners sad (‘ [. . .] wixt good and bad,)

‘ [. . .] wixt Heirs of woe, and bliss.

XXII

At Christ’s right hand the sheep do st [. . .] nd,

his Holy Martyrs who

For his dear Name, suffering shame,

calamity, and woe,

Like Champions stood, and with their blood

their Testimony sealed;

Whose innocence, without off [. . .] nce

to Christ their Judge appealed.

XXIII

Next unto whom there find a room,

all Christs [. . .] fflicted one [. . .],

Who being chastis’d, neither despis’d,

nor sank amidsts their g [. . .] oans:

Who by the Rod were turn’d to God,

and loved him the more,

N [. . .] murmuring nor quarrelling [. . .]

when they were chast’ned sore.

XXIV

Moreover such as loved much,

that had not such a trial,

As might constrain to so great pain,

and such deep sel [. . .]-denial;

Yet ready were the Cross to bear,

when Christ them call’d thereto,

And did rejoyce to hear his voice,

they’r counted Sheep also.

XXV

Christ’s flock of Lambs there also stands,

whose Faith was weak, yet true;

All sound Believers (Gospel-receivers)

whose grace was small, but grew.

And them among an infant throng

of Babes, for whom Christ dy’d;

Whom [. . .] or his own, by ways unknown.

to men, he sanctify’d.

Page | 190

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

XXVI

All stand before their Saviour

in long white Robes [. . .] clad,

Their countenance [. . .] ull of pleasance,

appearing wondrous glad.

O glorious sight I behold how bright

dust heaps are made to shine,

Conformed so their Lord unto,

whose glory is divine.

XXVII

At Christs left hand the Goats do stand,

all whining Hypocrites,

Who for self-ends did seem Christ’s friends,

but fost’red guileful sprites:

Who Sheep resembled, but they dissembled

(their heart was not sincere)

Who once did throng Christ’s Lambs among;

but now must not come near.

XXVIII

Apostata’s, and Run-away’s,

such as have Christ forsaken,

(Of whom the the Devil, with seven more evil,

hath fresh possession taken:

Sinners in grain, reserv’d to pain

and torments most severe)

Because ‘gainst light they sinn’d with spight,

are also placed there.

XXIX

There also stand a num’rous band,

that no profession made

Of Godliness, nor to redress

their wayes at all assay’d:

Who better knew, but (sin [. . .] ul Crew [. . .])

Gospel and Law despised;

Who all Christ’s knocks withstood like blocks,

and would not be advised.

XXX

Moreover there with them appear

a number numberless

Page | 191

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

Of great and small, vile wretches all,

that did Gods Law transgress:

Idolaters, false Worshippers,

Prophaners of Gods Name,

Who not at all thereon did call,

or took in vain the same.

XXXI

Blasphemers lewd, and Swearers shrewd,

Scoffers at Purity,

That hated God, contemn’d his Rod,

and lov’d security.

Sabbath-polluters, Saints Persecuters,

Presumptuous men, and Proud,

Who never lov’d those that reprov’d;

all stand amongst this crowd.

XXXII

Adulterers and Whoremongers

were there, with all unchast.

There Covetou [. . .] , and Ravenous,

that Riches got too fast:

Who us’d vile ways themselves to raise

t’ Estates and worldly wealth,

Oppression by, or Knavery,

by Force, or Fraud, or Stealth.

XXXIII

Moreover, there together were

Children fl [. . .] gitious,

And Parents who did them undo

by nature vicious.

False-witness-bearers, and self-forswearers,

Murd’rers and men of blood,

Witches, Inchanters, and Alehouse-haunters,

beyond account there stood.

XXXIV

Their place there find all Heathen blind,

that Natures light abused,

Although they had no tidings glad

of Gospel-grace re [. . .] used.

There stand all Nations and Generations

Page | 192

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

of Adam’s Progeny,

Whom Christ redeem’d not, who Christ esteem’d not

throught infidelity.

XXXV

Who no Peace-maker, no Undertaker

to shrowd them from God’s ire

Ever obtained; they must be pained

with everlasting fire.

These num’rous bands, wringing their hands,

and weeping, all stand there,

Filled with anguish, whose hearts do languish

through self-tormenting fear.

XXX

Fast by them stand at Christ’s left hand

the Lion fierce and fell,

The Dragon bold, that Serpent old

that hurried Souls to Hell.

There also stand, under command,

Legions of Sprights unclean.

And hellish Fiends that are no friends

to God, nor unto men.

XXXVII

With dismal chains and strong reins,

like prisoners of Hell,

They’r held in place before Christ’s face,

till he their Doom shall tell.

These void of tears, but fill’d with fears,

and dreadful expectation

Of endless pains, and scalding flames,

stand waiting for Damnation.

XXXVIII

All silence kept, both Goats and Sheep,

before the Judges Throne:

With mild aspect to his Elect

then spake the Holy One:

My Sheep draw near, your sentence hear,

which is to you no dread,

Who clearly now discern, and know

your sins are pardoned.

Page | 193

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

XXXIX

‘Twas meet that ye should judged be,

that so the world may ‘spy

No cause of grudge, when as I judge

and deal impartially,

Know therefore all both great and small,

the ground and reason why

These men do stand at my right hand,

and look so chearfully.

XL

These men be those my Father chose

before the world’s foundation,

And to me gave that I should save

from death and condemnation.

For whose dear sake I flesh did take,

was of a woman born,

And did inure my self t’endure

unjust reproach and scorn.

XLI

For them it was that I did pass

through sorrows many a one:

That I drank up that bitter Cup,

which made me sigh and groan.

The Cross his pain I did sustain;

yea more, my Fathers ire

I under-went, my bloud I spent

to save them from Hell fire.

XLII

Thus I esteem’d, thus I redeem’d

all these from every Nation,

that they might be (as now you see)

a chosen Generation.

What if ere-while they were as vile

and bad as any be,

[. . .] nd yet from all their guilt and thrall

at once I set them free?

XLIII

My grace to one is wrong to none:

none can Election claim.

Page | 194

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

Amongst all those their souls that lose,

none can Rejection blame.

He that may chuse, or else refuse,

all men to save or spill,

May this man chuse, and that refuse,

redeeming whom he will.

XLIV

But as for those whom I have chose

Salvations heirs to be,

I u [. . .] derwent their punishment,

and therefore set them free.

I bore their grief, and their relief

by suffering procur’d,

That they of bliss and happiness

[. . .] ight firmly be assur’d.

XLV

And this my g [. . .] ace they did embrace,

believing on my name;

Which Faith was true, the fruits do shew

proceeding from the same.

Their Penitence, their Patience,

their Love, their Self-den [. . .] al;

In suffering losses and bearing crosses,

when put upon the trial:

XLVI

Their sin forsaking, their cheerful taking

my yoke; their chari [. . .] ee

Unto the Saints in all their wants,

and in them unto me.

These things do clear, and make appear

their Faith to be unfeigned:

And that a part in my desert

and purchase they have gained.

XLVII

Their debts are paid, their peace is made,

their sins remitted are;

Therefore at once I do pronounce

and openly declare,

That Heaven is theirs, that they be Heir [. . .]

Page | 195

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

of Life and of Salvation;

Nor ever shall they come at all

to death or to damnation.

XLVIII

Come, blessed ones, and sit on Thrones,

judging the world with me:

Come, and possess your happiness,

and bought [. . .] elicitee.

Henceforth no fears, no care, no tears,

no sin shal you annoy,

Nor any thing that grief doth bring;

eternal rest enjoy.

XLIX

You bore the Cross, you suffered loss

of all [. . .] or my Names sake:

Receive the Crown that’s now your own;

come, and a kingdom take.

Thus spake the Judge: the wicked grudge,

and grind their teeth in vain;

They see with groans these plac’d on throne [. . .]

which addeth to their pain:

L

That those whom they did wrong and slay,

must now their judgement see!

Such whom they sleighted and once de [. . .] spighte [. . .]

must of their Judges be!

Thus ‘tis decreed, such is their meed

and guerdon glorious:

With Christ they sit, judging it fit

to plague the impious.

LI

The wicked are brought to the Bar

like guilty malefactors,

That oftentimes of bloody crimes

and treasons have been actors.

Of wicked men none are so mean

as there to be neglected:

Nor none so high in dignity,

as there to be respected.

Page | 196

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

LII

The glorious Judge will priviledge

nor Emperour nor King:

But every one that hath misdone

doth into judgement bring;

And every one that hath misdone,

the Judge impartially

Condemneth to eternal wo,

and endless misery.

LIII

Thus one and all, thus great and small,

the rich as well as poor,

And those of place, as the most base,

do stand their Judge before:

They are arraign’d, and there detain’d

before Christ’s judgement seat

With trembling fear their Doom to hear,

and feel his angers heat.

LIV

There Christ demands at all their hands

a strict and straight account

Of all things done under the Sun;

who [. . .] e numbers far surmount

Man’s wit and thought: yet all are brought

unto this solemn trial;

And each offence with evidence,

so that there’s no denial.

LV

There’s no excuses for their abuse [. . .]

since their own consciences

More proof give in of each man’s sin;

then thousand witnesses.

Though formerly this faculty

had grosly been abused,

(Men could it stifle, or with it trifle,

whenas it them accused.)

LVI

Now it comes in, and every si [. . .]

unto mans charge doth lay:

Page | 197

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

It judgeth them, and doth condemn,

though all the world say nay.

It so stingeth and tortureth,

it worketh such di [. . .] tress,

That each mans self against himself

is forced to confess.

LVII

It’s vain, moreover, for men to cover

the least iniquity;

The Judge hath seen and privy been

to all their villany.

He unto light and open sight

the works of darkness b [. . .] ings:

He doth unfold both new and old,

both known and hidden things.

LVIII

All filthy facts and secret acts,

however closely done

And long conceal’d, are there reveal’d.

before the mid-day Sun.

Deeds of the night shunning the light,

which darkest corners sought,

To fearful blame and endless shame,

are there most justly brought.

LIX

And as all facts and grosser acts,

so every word and thought,

Erroneous notion and lust [. . .] ul motion,

are into judg [. . .] ment brought.

No sin so small and trivial,

but hi [. . .] her it must come:

[. . .] or so long past, but now at last

it must receive a doom.

LX

[. . .] t this sad season Christ asks a reason

(with just austerity)

Of Grace refus’d, of Light abus’d

so oft, so wilfully:

O [. . .] Talents lent, by them-mispent,

Page | 198

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

and on their lusts bestown;

Which if improv’d as it behoov’d,

Heaven might have been their own.

LXI

Of time neglected, of meanes rejected,

of God’s long-suffering,

And patience, to penitence

that sought hard hearts to bring.

Why cords of love did nothing move

to shame or to remorse?

Why warnings grave, and councels have

nought chang’d their sinful course?

LXII

Why chastenings and evil [. . .] hings,

why judgments so severe

Prevailed not with them a jo [. . .],

nor wrought an awful fear?

Why promises of holiness,

and new obedience,

[. . .] hey oft did make, but always break

the [. . .] ame to Gods offence?

LXIII

Why, still Hell-ward, without regard,

the boldly ventured,

And chose Damnation before Salvation

when it was offered?

Why sinful pleasures and earthly treasures,

like fools they prized more

Then heavenly wealth, eternal health,

and all Christs Royal store?

LXIV

Why, when he stood off’ring his Bloud

to wash them from their sin,

They would embrace no saving Grace,

but liv’d and di’d therein?

Such aggravations, where no evasions

nor false pretences hold,

Exagerate and cumulate

guilt more then can be told:

Page | 199

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

LXV

They multiply and magnifie

mens gross iniquities;

They draw down wrath (as Scripture saith)

out of God’s treasuries [. . .]

Thu [. . .] all their ways Christ open lays

to Men and Angels view,

And, as they were, makes them appear

in their own proper hue.

LXVI

Thus he doth find of all ma [. . .] kind

that stand at his left hand

No mothers son but hath misdone,

and broken God’s command.

All have transgrest, even the best,

and merited God’s wrath

[. . .] nto their own perdition,

and everlasting scath.

LXVII

Earth’s dwellers all both great and small,

have wrought iniquity,

And suffer must (for it is just)

eternal misery.

Amongst the many there come not any

before the Judge’s face,

That able are themselves to clear,

of all this curled race.

LXVIII

Nevertheless they all express,

Christ granting liberty,

What for their way they have to say,

how they have liv’d, and why.

They all draw near, and seek to clear

themselves by making plea’s.

There hypocrites, false-hearted wights,

do make such pleas as these.

LXIX

Lord, in thy Name, and by the same

we Devils dispossest:

Page | 200

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

We rais’d the dead, and ministred

succour to the distrest.

Our painful preaching and pow’rful teaching,

by thine own wond’rous might,

Did throughly win from God to sin

many a wretched wight.

LXX

All this (quoth he) may granted be [. . .]

and your case little better’d,

Who still remain under a chain,

and many irons fetter’d.

You that the dead have quickened,

and rescu’d from the grave,

Your selves were dead, yet never ned

a Christ your Souls to save.

LXXI

You that could preach, and others teach

wh [. . .] t way to life doth lead;

Why were you slack to find that track,

and in that way to tread?

How could you bear to see or hear

of others freed at last

From Satans Paws, whilst in his jaws

your selves were held more fa [. . .] t?

LXXII

Who though you kne [. . .] Repentance true

and faith in my great Name,

The only mean to quit you clean

from punishment and blame,

Yet took no pain true faith to gain,

(such as might not deceive)

Nor would repent wi [. . .] h true intent

[. . .] our evil deeds to leave.

LXXIII

[. . .] is Masters will how to fulfil

[. . .] he servant that well knew,

[. . .] et left undone his duty known,

more plagues to him are due.

[. . .] ou against Light perverted Right;

Page | 201

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

[. . .] herefore it shall be now

[. . .] or Sidon and for Sodom’s Land

[. . .] ore easie then for you.

LXXIV

[. . .] ut we have in thy presence bin,

say some, and eaten there.

[. . .] id we not eat thy flesh for meat,

and feed on heavenly cheer?

Whereon who feed shall never need,

as thou thy self dost say,

[. . .] or shall they die eternally,

but live with thee for ay.

LXXV

We may alledge, thou gav’st a pledge

of thy dea [. . .] love to us

[. . .] Wine and B [. . .] e [. . .] d, [. . .] hich figured

[. . .] hy grace bestowed thus.

Of streng [. . .] hning seals, of s [. . .] eetest meals

have we so oft partaken?

[. . .] nd shall we be cast off by thee,

and utterly forsaken?

LXXVI

[. . .] whom the Lord thu [. . .] in a word

[. . .] eturns a short reply:

I never k [. . .] ew any of you

that wrought iniquity.

You say y’ have bin, my Presence in;

bu [. . .] , f [. . .] iends, how came you there

Wi [. . .] h Raiment vile, that did defile

and quite disgrace my cheer?

LXXVII

Durst you draw near without due fear

unto my holy Table?

Du [. . .] st you prophane and render vain

so far as you were able,

Those Mysteries? which whoso prize

and carefully improve,

Shall saved be undoubtedly,

and nothing shall them move.

Page | 202

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

LXXVIII

How du [. . .] st you venture, bold guests, to enter

in such a [. . .] ordid hi [. . .] e,

Amongst my guests, unto those feasts

that were not made for you?

How durst you eat for spir’tual meat

your bane, and drink damnation,

Whilst by your guile you rendred vile

so rare and great salvation?

LXXIX

Your fancies fed on heav’nly bread;

your hearts fed on some lust:

You lov’d the Creature more then th’Creator

your soules clave to the dust.

And think you by hypocrisie

and cloaked wickedness,

To enter in, laden with sin,

to lasting happiness.

LXXX

This your excuse shews your abuse

of things ordain’d for good;

And do declare you guilty are

of my dear Flesh and Bloud.

Wherefore those Seals and precious Meals

you put so much upon

As things divine, they seal and sign

you to perdition.

LXXXI

Then forth issue another Crew,

(those being silenced)

Who drawing nigh to the most High

adventure thus to plead:

We sinners were, say they, ‘tis clear,

deserving Condemnation:

But did not we rely on thee,

O Christ, for whole Salvation?

LXXXII

We did believe, and of receive

thy gracious Promises:

Page | 203

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

We took great care to get a share

in endless happiness:

We pray’d and wept, we Fast-days kept,

lewd ways we did eschew:

We joyful were thy Word to h [. . .] ar,

we fo [. . .] m’d our lives anew.

LXXXIII

We thought our sin had pardon’d bi [. . .],

that our estate was good,

Our debts all paid, [. . .] ur peace well made,

our Souls wash [. . .] wi [. . .] h [. . .] hy B [. . .] oud.

Lord, why dost thou rej [. . .] ct us now,

who have not thee rejected,

Nor utterly true sanctity

and holy li [. . .] e neglected?

LXXXIV

The Judge ince [. . .] sed at their pretenced

self-vaunting piety,

With such a look as trembling strook

into them, made reply;

O impudent, impeni [. . .] ent,

and guile [. . .] ul generation!

Think you that I cannot descry

your hearts abomination?

LXXXV

You not receiv’d, nor yet believ [. . .] d

my promises of grace;

Nor were you wise enough to prize

my reconciled face:

But did presume, that to assume

which was not yours to take,

And challenged the childrens bread,

yet would not sin forsake.

LXXXVI

B [. . .] ing too bold you laid fast hold

where int’ [. . .] est you had none,

Your selves deceiving by your believing;

all which you might have known.

You [. . .] an away (but ran astray)

Page | 204

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

with Gospel promises,

And perished, being still dead

in sins and trespasse [. . .].

LXXXVII

How oft did I hypocrisie

and hearts deceits unmask

Before your sight, giving you ligh [. . .]

to know a Christians task?

But you held fast unto the last

your own conceits so vain:

No warning could prevail, you would

your own deceits re [. . .] ain.

LXXXVIII

As for your care to get a share

in bliss, the fear of Hell,

And of a part in endless smart,

did thereunto compel.

Your holiness and ways redress,

such as it was, did spring

From no true love to things above,

but from some other thing.

LXXXIX

You pray’d and wept, you Fast-days kept,

but did you this to me?

No, but for [. . .] n you sought to win

the greater liberte [. . .].

For all your vaunts, you had vile haunt’s;

for which your consciences

Did you alarm, whose voice to charm

you us’d these practises.

XC

Your penitence, your diligence

to read, to pray, to hear,

Were but to drown the clam’rous sound

of conscience in your ea [. . .]

If light you lov’d, vain-glory mov’d

your selves therewith to store,

Th [. . .] t seeming wise, men might you prize,

and honour you the more.

Page | 205

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

XCI

Thus from your selves unto your selves

your duties all do tend:

And as self-love the wheels do move,

so in self-love they end.

Thus Ch [. . .] ist detects their vain projects,

and close impiety,

And plainly shews that all their shows

were but hypocrisie.

XCII

Then were brought nigh a company

of [. . .] ivil honest men,

That lov’d true dealing, and hated stealing,

[. . .] e wrong’d their brethren:

Who pleaded thus, Thou knowest us

that we were blamele [. . .] s livers;

No whore-mongers, no murderers,

no quarrellers nor strivers.

XCIII

Idolaters, Adulterers,

Church-robbers we were none;

Nor false dealers, nor couzeners,

but paid each man his own.

Our way was fair, our dealing square,

we were no wastful spenders,

No lewd toss-pots, no drunken sots,

no scandalous offenders.

XCIV

We hated vice, and set great price

by vertuous conversation:

And by the same we got a name,

and no small commendation.

God’s Laws express that righteousness

is that which he doth prize;

And to obey, as he doth say,

is more then sacrifice.

XCV

Thus to obey, hath been our way;

let our good deeds, we pray,

Page | 206

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

Find some regard, and good rewa [. . .] d

with thee, O Lord, this day.

And whereas we transgressors be;

of Adam’s Race were n [. . .] ne,

(No not the best) but have confes [. . .]

themselves to h [. . .] ve mis [. . .] one.

XCVI

Then answered, un [. . .] o their dread,

the Judge, True piety

God doth desire, and eke requi [. . .] e

no less then honesty.

Justice demands at all your hands

perfect Obedience:

If but in part you have come sh [. . .],

that is a just offence.

XCVII

On earth below where men did owe

a thousand pounds and more,

Could twenty pence it recompence?

could that have clear’d the score?

Think you to buy felicity

with part of what’s due debt?

O [. . .] for desert of one small part

the whole should off be set?

XCVIII

And yet that part (whose great desert

you think to reach so far

For your excuse) doth you accuse,

and will your boasting mar.

However fair, however square

your way, and work h [. . .] th bin

Before mens eyes, yet God espies

iniquity therein.

XCIX

God looks upon th’ [. . .] ff [. . .] ction

and temper of the heart;

Not only on the action,

and the external part.

Whatever end vain men pretend,

Page | 207

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

God knows the v [. . .] ri [. . .] y [. . .]

And by the end which they intend

their words and deeds doth try.

C

Without true faith, the Scripture saith,

God cannot take delight

In any deed, that doth proceed

from any si [. . .] ful wight.

And withou [. . .] love all actions prove

but barren empty things:

Dead works they be, and vanity,

the which vexation brings.

CI

Nor from true faith, which quencheth wrath

hath your obedience flown:

Nor from true love, which wont to move

believers, hath it grown.

Your argument shews your intent

in all that you have done:

You thought to [. . .] cale heavens lofty wall,

by ladders o [. . .] your own.

CII

Your blinded spirit, hoping to merit

by your own righteousness,

Needed no Saviour, but your b [. . .] haviour

and blameless ca [. . .] riages [. . .]

You trusted to what you could do,

and in no need you stood:

Your haughty pride laid me aside,

and trampled on my Bloud.

CIII

All men have gone astray, and done

that which God’s Law [. . .] condemn:

But my Purchase and offered Grace

all men did not contemn.

The Ninevites and Sodomites

had no such sin as this:

Yet as if all your sins were small,

you say, All did amiss.

Page | 208

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

CIV

Again, you thought, and mainly sought

a name with men t’ acquire:

Pride bare the B [. . .] ll that made you swell,

and your own selves admire.

M [. . .] an frui [. . .] it is, and vile, I wis,

that sp [. . .] ings from such a root:

Vertue divine and genuine

wants not from pride to shoor.

CV

Such deeds as you are worse then poo [. . .],

they are but sins guilt over

With silver dross, whose glistering gloss

[. . .] an them no longer cover.

The best of them would you condemn,

and [. . .] uine you alone,

Al [. . .] hough you were from faults so clear,

that other you had none.

CVI

Your gold is dross, you [. . .] silver brass,

your righteousness is sin:

And think you by such honesty

Eternall life to win?

You much mistake, if for it’s sake

you dream of acceptation;

Whereas the same deserveth shame,

and meriteth damnation.

CVII

A wond’rous Crowd then ‘gan aloud

thus for themselves to say;

We did intend, Lord to mend,

and to reform our way:

Ou [. . .] true intent was to repent,

and make our peace with thee;

But sudden death stopping our breath,

left us no libertee.

CVIII

Short was our time; for in his prime

our youthful flow’r was cropt:

Page | 209

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

We dy’d in youth, before full growth;

so was our purpose stopt.

Let our good will to turne from ill,

and sin to have forsaken,

Accepted be O Lord, by thee,

and in good part be taken.

CIX

To whom the Judg; Where you alledge

the shortness of the space

That from your bi [. . .] th you liv’d on earth,

to compass S [. . .] ving Grace:

It was free-grace, that any space

wa [. . .] given you at all

To turn from evil, defie the Devil,

and upon God to call.

CX

One day, one week, wherein to seek

Gods face with all your hearts,

A favour was that far did pass

the best of your deserts.

You had a season; what was your Reason

such preciou [. . .] hours to waste?

What could you find, what could you mind

that was of greater haste?

CXI

Could you find time for vain pastime?

for loose licentious mirth?

For fruitless toys, and fading joyes

that perish in the birth?

Had you good leisure for Carnal pleasure

in days of health and youth?

And yet no space to seek Gods face,

and turn to him in truth?

CXII

In younger years, beyond your fears,

what if you were surprised?

You put away the evil day,

and of long life devised.

You oft were told, and might behold,

Page | 210

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

that Death no age would spare.

Why then did you your time foreslow,

and slight your Souls welfare?

CXIII

H [. . .] d your intent been to Repent,

and had you it desir’d,

There would have been endeavours seen

before your time expir’d.

God makes no [. . .] reasure nor hath he pleasure

in idle purpo [. . .] es:

Such fair pretences are foul offences,

and cloaks for wickedness.

CXIV

Then were brought in and charg’d with sin

another Compa [. . .] y,

Who by Petition obtain’d permission

to make apology:

They argued; We were mis-led,

as is well known to thee,

By their Example, that had more ample

abilities than we.

CXV

Such as profest we did detest

and hate each wicked way:

Whose seeming grace whil’st we did trace,

our Souls were led astray.

When men of Parts, Learning and Arts,

professing Piety,

Did thus and thus, it seem’d to us

we might take liberty.

CXVI

The Judge Replies; I gave you eyes,

a [. . .] d light to see your way:

Which had you lov’d and well improv’d

you had not gone astray.

My Word was pure, the Rule was sure;

why did you it forsake,

Or thereon trample, and men’s Example

your Directory make?

Page | 211

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

CXVII

This you well know, that God is true,

and that most men are liars,

In word professing holiness,

in deed thereof deniers [. . .]

O simple [. . .] ools! that having Rules

your lives to Regulate,

Would them refuse, and rather chuse

vile men to imitate.

CXVIII

But Lord, say they, we we [. . .] astray,

and did more wickedly,

By means of those whom thou hast chose

Salvations Heirs to be.

To whom the Judge; What you alledge

doth nothing help the case,

But makes appear how vile you were,

and rend’reth you more ba [. . .] e.

CXIX

You understood that what was good

was to be [. . .] ollowed,

And that you ought that which was nought

to have relinquished.

Contrariwise, it was your guise,

only to imitate

Good mens defects, and their neglects

that were Regenerate.

CXX

But to express their holiness,

or imitate their Grace,

Yet little ca [. . .] ‘d, not once prepar’d

your hearts to seek my face.

They did Repent, and truly Rent

their hearts for all known sin:

You did Offend, but not Amend,

to follow them therein.

CXXI

We had thy Word, (said some) O Lord,

but wiser men then wee

Page | 212

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

Could never yet interpret it,

but always disagree.

How could we fools be led by Rules

so far beyond our ken,

Which to explain, did so much pain

and puzzle wisest men?

CXXII

Was all my Word obscure and hard?

the Judge then answered:

It did contain much Truth so plain,

you might have run and read.

But what was hard you never car’d

to know, nor studied:

And things that were most plain and clear,

you never practised.

CXXIII

The Mystery of Pie [. . .] y

God unto Babes reveals;

When to the wise he it denies,

and from the world co [. . .] ceals.

If [. . .] o fulfill Gods holy will

had seemed good to you,

You would have sought light as you ought,

and done the good y [. . .] u knew.

CXXIV

Then came in view ano [. . .] her Crew,

and ‘gan to make their plea’s;

Amongst the rest, some of the best

had such poor [. . .] hifts as these:

Thou know’st right well, who all canst tell,

we liv’d amongst thy foes,

Who the Renate did sorely hate,

and goodness much oppose.

CXXV

We Holiness durst not profess,

fearing to be forlorn

Of all our friends, and for amends

to be the wicked’s scorn.

We knew thei [. . .] anger would much endanger

Page | 213

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

our lives and our estates:

Therefore for fear we durst appear

no better than our mates.

CXXVI

To whom the Lord returns this word;

O wonderful deceits!

To cast off aw of Gods strict Law,

and fear mens wrath and th [. . .] eats!

To fear Hell-fire and Gods fierce ire

less then the rage of men!

As if Gods wrath could do less scath

than wrath of bretheren!

CXXVII

To use such strife to temp’ral life

to rescue and secure!

And be so b [. . .] ind as not to mind

that life that will endure!

This was you [. . .] case, who carnal peace

more then [. . .] ue joyes did savour:

Who fed on dus [. . .] , clave to your lust,

and spurned at my [. . .] avour.

CXXVIII

To please your kin, mens loves to win,

to flow in wo [. . .] ldly wealth,

To save your skin, these things have bin

more than Eternal health.

You had your choice, wherein rejoyce,

it was your portion,

For which you chose your Souls t’ expose

unto Perdition.

CXXIX.

Who did not hate friends, life, and state,

with all things else for me,

And all forsake, and’s Cross up take,

shall never happy be.

Well worthy they do die for ay,

who death then life had rather:

Death is their due that so value

the friendship of my Father.

Page | 214

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

CXXX

Others argue, and not a few,

is not God gracious?

His Equity and Clemency

are they not marvellous?

Thus we believ’d; are we deceiv’d?

cannot his Mercy great,

(As hath been told to us of old)

asswage his anger’s heat?

CXXXI

How can it be that God should see

his Creatures endless pain?

O [. . .] hear their groans or ruefull moanes,

and still his wrath retain?

Can it agree with equitee?

can Mercy have the heart,

To Recompence few years offence

with Everlasting smart?

CXXXII

Can God delight in such a sight

as sinners Misery?

Or what great good can this our bloud

bring unto the most High?

Oh thou that dost thy Glory most

in pard’ning sin display!

Lord! might it please thee to release,

and pardon us this day?

CXXXIII

Unto thy Name more glorious fame

would not such Mercy bring?

Would it not raise thine endless praise,

more than our suffering?

With that they cease, holding their peace,

but cease not still to weep;

Griefe ministers a flood to tears,

in which their words do steep:

CXXXIV

But all too late; Grief’s out of date

when Life is at an end.

Page | 215

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

The glorious King thus answering,

all to his voice attend:

God gracious is, quoth he, like his

no Mercy can be found;

His Equity and Clemency

to sinners do abound.

CXXXV

As may appear by those that here

are plac’d at my right hand;

Whose stripes I bore and clear’d the score

that they might quitted stand.

For surely none but God alone,

whose Grace transcends man’s thought,

For such as those that were his foes

like wonders would have wrought.

CXXXVI

And none but he such lenitee

and patience would have shown

To you so long, who did him wrong,

and pull’d his judgements down.

How long a space (O stiff-neck’t Race!)

did patience you afford?

How oft did love you gently move

to turn unto the Lord?

CXXXVII

With cords of Love God often strove

your stubborn hearts to tame:

Nevertheless, your wickedness

did still resist the same.

If now at last Mercy be past

from you for evermore,

And Justice come in Mercies room,

yet grudge you no [. . .] therefore.

CXXXVIII

If into wrath God tu [. . .] ed hath

his Long-long [. . .] uffe [. . .] ing,

And now for Love you Vengeance prove,

it is an equal thing.

Your waxing worse, hath stopt the course

Page | 216

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

of wonted Clemency:

Mercy refus’d, and Grace misus’d,

call for severity.

CXXXIX

It’s now high time that every Crime

be brought to punishment:

VVrath long contain’d, and oft refrain’d,

at last must have a vent.

Justice [. . .] evere cannot fo [. . .] bear

to plague sin any longer;

But must inflict with hand mo [. . .] t strict

mischief upon the wronger.

CXL

In vain do they for Mercy pray,

the season being past,

Who had no care to get a share

therein, while time did last.

The men whose ear refus’d to hear

the voice of Wisdom’s cry,

Earn’d this reward, that none regard

him in his misery.

CXLI

It doth agree with Equitee,

and with God’s holy Law,

That those should dy eternally,

that death upon them draw.

The Soul that sin’s damnation win’s;

for so the Law ordains:

Which Law is just [. . .] and therefore must

such suffer endless pains.

CXLII

Etern [. . .] l smart is the desert

ev’n of the least offence;

Then wonder not if I allot

to you this Recompence:

But wonder more that, since so sore

and lasting plagues are due

To every sin, you liv’d therein,

who well the danger knew.

Page | 217

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

CXLIII

God hath no joy to crush or ‘stroy,

and ruine wretched wights:

But to display the glorious ray

of Justice he delights.

To manifest he doth detest

and throughly hate all sin,

By plaguing it, as is most fit,

this shall him glory win.

CXLIV

Then at the Bar arraigned are

an impudenter sort,

Who to evade the guilt that’s laid

upon them, thus retort;

How could we cease thus to transgress?

how could we Hell avoid,

Whom God’s Decree shut out from thee,

and sign’d to be destroy’d?

CXLV

Whom God ordains to endless pains

by Laws unalterable,

Repentance true, Obedience new,

to save such are unable:

Sorrow for sin no good can win

to such as are rejected;

Ne can they give, not yet believe

that never were elected.

CXLVI

Of man’s faln Race who can true Grace

or Holiness obtain?

Who can convert or change his heart,

if God with-hold the same?

Had we apply’d our selves, and tri’d

as much as who did most

Gods love to gain, our busie pain

and labour had been lost.

CXLVII

Christ readily makes this reply;

I damn you not because

You are rejected, or not elected;

Page | 218

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH COLONIAL LITERATURE

but you have broke my Laws.

It is but vain your wits to strain

the E [. . .] d and Me [. . .] ns to sever:

Men fondly seek to dart or break

what God hath link’d together.

CXLVIII

Whom God will save, such he will have

the means of life to use:

Whom he’l pass by, shall chuse to di [. . .],

and ways of life refuse.

He that fore-sees and fore-decrees,

in wisdom order’d has,

That man’s free-will electing ill

shall bring his Will to pass.

CXLIX

High God’s Decree, as it is free,

so doth it none compel

Against their will to good or ill;

i [. . .] forceth none to Hell.

They have their wish whose Souls perish

with torments in Hell-fire:

Who rather chose their souls to lose,

then leave a loose desire.

CL

God did ordain sinners to pain;

and I to hell send none,

But such as swe [. . .] v’d, and have deserv’d

destruction as their own.

His pleasure is, that none fr [. . .] ss

and endless happiness

Be barr’d, but such as wrong [. . .] much