7.7: Macedonian Conquest

- Page ID

- 46118

The Rise of the Macedon

Philip II’s conquests during the Third Sacred War cemented his power, as well as the influence of Macedon, throughout the Hellenic world.

Learning Objectives

Describe Philip II’s achievements and how he built up Macedon

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The military skills Philip II learned while in Thebes, coupled with his expansionist vision of Macedonian greatness, brought him early successes when he ascended to the throne in 359 BCE.

- Philip earned immense prestige, and secured Macedon ’s position in the Hellenic world during his involvement in the Third Sacred War, which began in Greece in 356 BCE.

- War with Athens would arise intermittently for the duration of Philip’s campaigns, due to conflicts over land, and/or with allies.

- In 337 BCE, Philip created and led the League of Corinth, a federation of Greek states that aimed to invade the Persian Empire.

- In 336 BCE, Philip was assassinated during the earliest stages of the League of Corinth’s Persian venture.

- Many Macedonian institutions and demonstrations of power mirrored established Achaemenid conventions.

Key Terms

- sarissas: A long spear or pike about 13-20 feet in length, used in ancient Greek and Hellenistic warfare, that was initially introduced by

Philip II of Macedon.

Macedon rose from a small kingdom on the periphery of classical Greek affairs, to a dominant player in the Hellenic world and beyond, within the span of 25 years between 359 and 336 BCE. Macedon’s rise is largely attributable to the policies during Philip II’s rule.

Background

In the aftermath of the Peloponnesian War, Sparta rose as a hegemonic power in classical Greece. Sparta’s dominance was challenged by many Greek city-states who had traditionally been independent during the Corinthian War of 395-387 BCE. Sparta prevailed in the conflict, but only because Persia intervened on their behalf, demonstrating the fragility with which Sparta held its power over the other Greek city-states. In the next decade, the Thebans revolted against Sparta, successfully liberating their city-state, and later defeating the Spartans at the Battle of Leuctra (371 BCE). Theban general Epaminondas then led an invasion of the Peloponnesus in 370 BCE, invaded Messenia, and liberated the helots, permanently crippling Sparta.

These series of events allowed the Thebans to replace Spartan hegemonic power with their own. For the next nine years, Epaminondas and Theban general Pelopidas further extended Theban power and influence via a series of campaigns throughout Greece, bringing almost every city-state in Greece into the conflict. These years of war ultimately left Greece war-weary and depleted, and during Epaminondas’s fourth invasion of the Peloponnesus in 362 BCE, Epaminondas was killed at the Battle of Mantinea. Although Thebes emerged victorious, their losses were heavy, and the Thebans returned to a defensive policy, allowing Athens to reclaim its position at the center of the Greek political system for the first time since the Peloponnesian War. The Athenians’ second confederacy would be Macedon’s main rivals for control of the lands of the north Aegean.

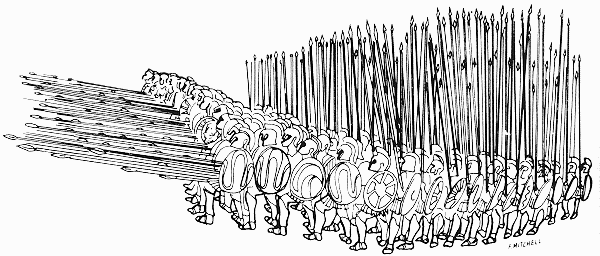

Philip II’s Accession

While Philip was young, he was held hostage in Thebes, and received a military and diplomatic education from Epaminondas. By 364 BCE, Philip returned to Macedon, and the skills he learned while in Thebes, coupled with his expansionist vision of Macedonian greatness, brought him early successes when he ascended to the throne in 359 BCE. When he assumed the throne, the eastern regions of Macedonia had been sacked and invaded by the Paionians, and the Thracians and the Athenians had landed a contingent on the coast at Methoni. Philip pushed the Paionians and Thracians back, promising them tributes, and defeated the 3,000 Athenian hoplites at Methoni. In the interim between conflicts, Philip focused on strengthening his army and his overall position domestically, introducing the phalanx infantry corps and arming them with long spears, called sarissas.

In 358 BCE, Philip marched against the Illyrians, establishing his authority inland as far as Lake Ohrid. Subsequently, he agreed to lease the gold mines of Mount Pangaion to the Athenians in exchange for the return of the city of Pydna to Macedon. Ultimately, after conquering Amphipolis in 357 BCE, he reneged on his agreement, which led to war with Athens. During that conflict, Philip conquered Potidaea, but ceded it to the Chalkidian League of Olynthus, with which he was allied. A year later, he also conquered Crenides and changed its name to Philippi, using the gold from the mines there to finance subsequent campaigns.

Third Sacred War

Philip earned immense prestige and secured Macedon’s position in the Hellenic world during his involvement in the Third Sacred War, which began in Greece in 356 BCE. Early in the war, Philip defeated the Thessalians at the Battle of Crocus Field, allowing him to acquire Pherae and Magnesia, which was the location of an important harbor, Pagasae. He did not attempt to advance further into central Greece, however, because the Athenians occupied Thermopylae. Although there were no open hostilities between the Athenians and Macedonians at the time, tensions had arisen as a result of Philip’s recent land and resource acquisitions. Instead, Philip focused on subjugating the Balkan hill-country in the west and north, and attacking Greek coastal cities, many of which Philip maintained friendly relations with, until he had conquered their surrounding territories. Nonetheless, war with Athens would arise intermittently for the duration of Philip’s campaigns, due to conflicts over land and/or with allies.

Persian Influences

For many Macedonian rulers, the Achaemenid Empire in Persia was a major sociopolitical influence, and Philip II was no exception. Many institutions and demonstrations of his power mirrored established Achaemenid conventions. For example, Philip established a Royal Secretary and Archive, as well as the institution of Royal Pages, which would mount the king on his horse in a manner very similar to the way in which Persian kings were mounted. He also aimed to make his power both political and religious in nature, utilizing a special throne stylized after those of the Achaemenid court, to demonstrate his elevated rank. Achaemenid administrative practices were also utilized in Macedonia rule of conquered lands, such as Thrace in 342-334 BCE.

In 337 BCE, Philip created and led the League of Corinth. Members of the league agreed not to engage in conflict with one another unless their aim was to suppress revolution. Another stated aim of the league was to invade the Persian Empire. Ironically, in 336 BCE, Philip was assassinated during the earliest stages of the Persian venture, during the marriage of his daughter Cleopatra to Alexander I of Epirus.

Alexander the Great

In a little over 30 years, Alexander the Great created one of the largest empires in the ancient world, using his military and tactical genius.

Learning Objectives

Examine Alexander the Great’s successes and failures

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Alexander the Great spent most of his ruling years on an unprecedented military campaign through Asia and northeast Africa. By the age of 30, he created an empire that stretched from Greece to Egypt, and into present-day Pakistan.

- Alexander inherited a strong kingdom and experienced army, both of which contributed to his successes.

- Alexander’s legacy includes the cultural diffusion his engendered conquests, and the rise of Hellenistic culture as a result of his military campaigns.

- Alexander’s impressive record was largely due to his smart use of terrain, phalanx and cavalry tactics, bold and adaptive strategy, and the fierce loyalty of his troops.

Key Terms

- phalanx: A rectangular mass military formation, usually composed entirely of heavy infantry armed with spears, pikes, sarissas, or similar weapons.

- Alexander the Great: Formally Alexander III of Macedon, a Macedonian king who was undefeated in battle and is considered one of history’s most successful commanders.

- Philip II: A king of the Greek kingdom of Macedon from 359 BCE until his assassination in 336 BCE. He was the father of Alexander the Great.

Following the decline of the Greek city-states, the Greek kingdom of Macedon rose to power under Philip II. Alexander III, commonly known as Alexander the Great, was born to Philip II in Pella in 356 BCE, and succeeded his father to the throne at the age of 20. He spent most of his ruling years on an unprecedented military campaign through Asia and northeast Africa, and by the age of 30, had created one of the largest empires of the ancient world, which stretched from Greece to Egypt and into present-day Pakistan. He was undefeated in battle and is considered one of history’s most successful commanders.

During his youth, Alexander was tutored by the philosopher Aristotle, until the age of 16. When he succeeded his father to the throne in 336 BCE, after Philip was assassinated, Alexander inherited a strong kingdom and an experienced army. He had been awarded the generalship of Greece, and used this authority to launch his father’s military expansion plans. In 334 BCE, he invaded the Achaemenid Empire, ruled Asia Minor, and began a series of campaigns that lasted ten years. Alexander broke the power of Persia in a series of decisive battles, most notably the battles of Issus and Gaugamela. He overthrew the Persian King Darius III, and conquered the entirety of the Persian Empire. At that point, his empire stretched from the Adriatic Sea to the Indus River.

Seeking to reach the “ends of the world and the Great Outer Sea,” he invaded India in 326 BCE, but was eventually forced to turn back at the demand of his troops. Alexander died in Babylon in 323 BCE, the city he planned to establish as his capital, without executing a series of planned campaigns that would have begun with an invasion of Arabia. In the years following his death, a series of civil wars tore his empire apart, resulting in several states ruled by the Diadochi, Alexander’s surviving generals and heirs. Alexander’s legacy includes the cultural diffusion his engendered conquests. He founded some 20 cities that bore his name, the most notable being Alexandria in Egypt. Alexander’s settlement of Greek colonists, and the spread of Greek culture in the east, resulted in a new Hellenistic civilization, aspects of which were still evident in the traditions of the Byzantine Empire in the mid-15th century. Alexander became legendary as a classical hero in the mold of Achilles, and he features prominently in the history and myth of Greek and non-Greek cultures. He became the measure against which military leaders compared themselves, and military academies throughout the world still teach his tactics.

Military Generalship

Alexander earned the honorific epithet “the Great” due to his unparalleled success as a military commander. He never lost a battle, despite typically being outnumbered. His impressive record was largely due to his smart use of terrain, phalanx and cavalry tactics, bold strategy, and the fierce loyalty of his troops. The Macedonian phalanx, armed with the sarissa, a spear up to 20 feet long, had been developed and perfected by Alexander’s father, Philip II. Alexander used its speed and maneuverability to great effect against larger, but more disparate, Persian forces. Alexander also recognized the potential for disunity among his diverse army, due to the various languages, cultures, and preferred weapons individual soldiers wielded. He overcame the possibility of unrest among his troops by being personally involved in battles, as was common among Macedonian kings.

In his first battle in Asia, at Granicus, Alexander used only a small part of his forces— perhaps 13,000 infantry, with 5,000 cavalry—against a much larger Persian force of 40,000. Alexander placed the phalanx at the center, and cavalry and archers on the wings, so that his line matched the length of the Persian cavalry line. By contrast, the Persian infantry was stationed behind its cavalry. Alexander’s military positioning ensured that his troops would not be outflanked; further, his phalanx, armed with long pikes, had a considerable advantage over the Persians’ scimitars and javelins. Macedonian losses were negligible compared to those of the Persians.

At Issus in 333 BCE, his first confrontation with Darius, he used the same deployment, and again the central phalanx pushed through. Alexander personally led the charge in the center and routed the opposing army. At the decisive encounter with Alexander at Gaugamela, Darius equipped his chariots with scythes on the wheels to break up the phalanx and equipped his cavalry with pikes. Alexander in turn arranged a double phalanx, with the center advancing at an angle, which parted when the chariots bore down and reformed once they had passed. The advance proved successful and broke Darius’s center, and Darius was forced to retreat once again.

When faced with opponents who used unfamiliar fighting techniques, such as in Central Asia and India, Alexander adapted his forces to his opponents’ style. For example, in Bactria and Sogdiana, Alexander successfully used his javelin throwers and archers to prevent outflanking movements, while massing his cavalry at the center. In India, confronted by Porus’s elephant corps, the Macedonians opened their ranks to envelop the elephants, and used their sarissas to strike upwards and dislodge the elephants’ handlers.

Alexander’s Empire

Alexander the Great’s legacy was the dissemination of Greek culture throughout Asia.

Learning Objectives

Describe the legacy Alexander left within his conquered territories

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Alexander’s campaigns greatly increased contacts and trade between the East and West, and vast areas to the east were significantly exposed to Greek civilization and influence. Successor states remained dominant for the next 300 years during the Hellenistic period.

- Over the course of his conquests, Alexander founded some 20 cities that bore his name, and these cities became centers of culture and diversity. The most famous of these cities is Egypt’s Mediterranean port of Alexandria.

- Hellenization refers to the spread of Greek language, culture, and population into the former Persian empire after Alexander’s conquest.

- Alexander’s death was sudden and his empire disintegrated into a 40-year period of war and chaos in 321 BCE. The Hellenistic world eventually settled into four stable power blocks: the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt, the Seleucid Empire in the east, the Kingdom of Pergamon in Asia Minor, and Macedon.

Key Terms

- Hellenization: The spread of Greek language, culture, and population into the former Persian empire after Alexander’s conquests.

Alexander’s legacy extended beyond his military conquests. His campaigns greatly increased contacts and trade between the East and West, and vast areas to the east were exposed to Greek civilization and influence. Some of the cities he founded became major cultural centers, and many survived into the 21st century. His chroniclers recorded valuable information about the areas through which he marched, while the Greeks themselves attained a sense of belonging to a world beyond the Mediterranean.

Hellenistic Kingdoms

Alexander’s most immediate legacy was the introduction of Macedonian rule to huge swathes of Asia. Many of the areas he conquered remained in Macedonian hands or under Greek influence for the next 200 to 300 years. The successor states that emerged were, at least initially, dominant forces, and this 300 year period is often referred to as the Hellenistic period.

The eastern borders of Alexander’s empire began to collapse during his lifetime. However, the power vacuum he left in the northwest of the Indian subcontinent directly gave rise to one of the most powerful Indian dynasties in history. Taking advantage of this, Chandragupta Maurya (referred to in Greek sources as Sandrokottos), of relatively humble origin, took control of the Punjab, and with that power base proceeded to conquer the Nanda Empire.

Hellenization

The term “Hellenization” was coined to denote the spread of Greek language, culture, and population into the former Persian empire after Alexander’s conquest. Alexander deliberately pursued Hellenization policies in the communities he conquered. While his intentions may have simply been to disseminate Greek culture, it is more likely that his policies were pragmatic in nature and intended to aid in the rule of his enormous empire via cultural homogenization. Alexander’s Hellenization policies can also be viewed as a result of his probable megalomania. Later his successors explicitly rejected these policies. Nevertheless, Hellenization occurred throughout the region, accompanied by a distinct and opposite “Orientalization” of the successor states.

The core of Hellenistic culture was essentially Athenian. The close association of men from across Greece in Alexander’s army directly led to the emergence of the largely Attic-based koine (or “common”) Greek dialect. Koine spread throughout the Hellenistic world, becoming the lingua franca of Hellenistic lands, and eventually the ancestor of modern Greek. Furthermore, town planning, education, local government, and art during the Hellenistic periods were all based on classical Greek ideals, evolving into distinct new forms commonly grouped as Hellenistic.

The Founding of Cities

Over the course of his conquests, Alexander founded some 20 cities that bore his name, most of them east of the Tigris River. The first, and greatest, was Alexandria in Egypt, which would become one of the leading Mediterranean cities. The cities’ locations reflected trade routes, as well as defensive positions. At first, the cities must have been inhospitable, and little more than defensive garrisons. Following Alexander’s death, many Greeks who had settled there tried to return to Greece. However, a century or so after Alexander’s death, many of these cities were thriving with elaborate public buildings and substantial populations that included both Greek and local peoples.

Alexander’s cities were most likely intended to be administrative headquarters for his empire, primarily settled by Greeks, many of whom would have served in Alexander’s military campaigns. The purpose of these administrative centers was to control the newly conquered subject populations. Alexander attempted to create a unified ruling class in conquered territories like Persia, often using marriage ties to intermingle the conquered with conquerors. He also adopted elements of the Persian court culture, adopting his own version of their royal robes, and imitating some court ceremonies. Many Macedonians resented these policies, believing hybridization of Greek and foreign cultures to be irreverent.

Alexander’s attempts at unification also extended to his army. He placed Persian soldiers, some of who had been trained in the Macedonian style, within Macedonian ranks, solving chronic manpower problems.

Division of the Empire

Alexander’s death was so sudden that when reports of his death reached Greece, they were not immediately believed. Alexander had no obvious or legitimate heir because his son, Alexander IV, was born after Alexander’s death. According to Diodorus, an ancient Greek historian, Alexander’s companions asked him on his deathbed to whom he bequeathed his kingdom. His laconic reply was, tôi kratistôi (“to the strongest”). Another, more plausible, story claims that Alexander passed his signet ring to Perdiccas, a bodyguard and leader of the companion cavalry, thereby nominating him as his official successor.

Perdiccas initially did not claim power, instead suggesting that Alexander’s unborn baby would be king, if male. He also offered himself, Craterus, Leonnatus, and Antipater, as guardians of Alexander’s unborn child. However, the infantry rejected this arrangement since they had been excluded from the discussion. Instead, they supported Alexander’s half-brother, Philip Arrhidaeus, as Alexander’s successor. Eventually the two sides reconciled, and after the birth of Alexander IV, Perdiccas and Philip III were appointed joint kings, albeit in name only.

Dissension and rivalry soon afflicted the Macedonians. After the assassination of Perdiccas in 321 BCE, Macedonian unity collapsed, and 40 years of war between “The Successors” (Diadochi) ensued, before the Hellenistic world settled into four stable power blocks: the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt, the Seleucid Empire in the east, the Kingdom of Pergamon in Asia Minor, and Macedon. In the process, both Alexander IV and Philip III were murdered.

The Legacy of Alexander the Great

Four stable power blocks emerged following the death of Alexander the Great: the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt, the Seleucid Empire, the Attalid Dynasty of the Kingdom of Pergamon, and Macedon.

Learning Objectives

Evaluate Alexander the Great’s legacy as carried out by his successors

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- After the assassination of Perdiccas in 321 BCE, Macedonian unity collapsed, and 40 years of war between “The Successors” ( Diadochi ) ensued before the Hellenistic world settled into four stable power blocks: the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt, the Seleucid Empire, the Kingdom of Pergamon in Asia Minor, and Macedon.

- The Ptolemaic Kingdom was ruled by the Ptolemaic dynasty, starting with Ptolemy I Soter’s accession to the throne following the death of Alexander the Great. The dynasty survived until the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BCE, at which point Egypt was conquered by the Romans.

- Although the Ptolemaic Kingdom observed the Egyptian religion and customs, Greek inhabitants were treated as a privileged minority.

- The Seleucid Empire was a major center of Hellenistic culture where Greek customs prevailed and the Greek political elite dominated, though mostly in urban areas.

- The Attalid kingdom of Pergamon began as a rump state, but was expanded by subsequent rulers.

- The Attalids were some of the most loyal supporters of Rome in the Hellenistic world and were known for their generous and intelligent rule.

- The Macedonian regime is the only successor state to Alexander the Great’s empire that maintained archaic perceptions of kingship, and elided the adoption of Hellenistic monarchical customs.

Key Terms

- proskynesis: A traditional Persian act of bowing or prostrating oneself before a person of higher social rank.

- satrap: A governor of a province in the Hellenistic empire. The word is also used metaphorically to refer to leaders who are heavily influenced by larger superpowers or hegemonies, and regionally act as a surrogate for those larger players.

Background

Alexander’s death was so sudden that when reports of his death reached Greece, they were not immediately believed. Alexander had no obvious or legitimate heir because his son, Alexander IV, was born after Alexander’s death. According to Diodorus, an ancient Greek historian, Alexander’s companions asked him on his deathbed to whom he bequeathed his kingdom. His laconic reply was tôi kratistôi (“to the strongest”). Another, more plausible, story claims that Alexander passed his signet ring to Perdiccas, a bodyguard and leader of the companion cavalry, thereby nominating him as his official successor.

Perdiccas initially did not claim power, instead suggesting that Alexander’s unborn baby would be king, if male. He also offered himself, Craterus, Leonnatus, and Antipater, as guardians of Alexander’s unborn child. However, the infantry rejected this arrangement since they had been excluded from the discussion. Instead, they supported Alexander’s half-brother, Philip Arrhidaeus, as Alexander’s successor. Eventually the two sides reconciled, and after the birth of Alexander IV, Perdiccas and Philip III were appointed joint kings, albeit in name only.

Dissension and rivalry soon afflicted the Macedonians. After the assassination of Perdiccas in 321 BCE, Macedonian unity collapsed, and 40 years of war between “The Successors” (Diadochi) ensued before the Hellenistic world settled into four stable power blocks: the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt, the Seleucid Empire in the east, the Kingdom of Pergamon in Asia Minor, and Macedon. In the process, both Alexander IV and Philip III were murdered.

The Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt

The Ptolemaic Kingdom was a Hellenistic kingdom based in Egypt, and ruled by the Ptolemaic dynasty, starting with Ptolemy I Soter’s accession to the throne following the death of Alexander the Great. The Ptolemaic dynasty survived until the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BCE, at which point Egypt was conquered by the Romans. Ptolemy was appointed as satrap of Egypt in 323 BCE, by Perdiccas during the succession crisis that erupted following Alexander the Great. From that time, Ptolemy ruled Egypt nominally in the name of joint kings Philip III and Alexander IV. As Alexander the Great’s empire disintegrated, however, Ptolemy established himself as a ruler in his own right. In 321 BCE, Ptolemy defended Egypt against an invasion by Perdiccas. During the Wars of the Diadochi (322-301 BCE), Ptolemy further consolidated his position within Egypt and the region by taking the title of King.

Early in the Ptolemaic dyansty, Egyptian religion and customs were observed, and magnificent new temples were built in the style of the old pharaohs. During the reign of Ptolemies II and III, thousands of Macedonian veterans were rewarded with farm land grants, and settled in colonies and garrisons throughout the country. Within a century, Greek influence had spread throughout the country and intermarriage produced a large Greco-Egyptian educated class. Despite this, the Greeks remained a privileged minority in Ptolemaic Egypt. Greek individuals lived under Greek law, received a Greek education, were tried in Greek courts, and were citizens of Greek cities, rather than Egyptian cities.

The Seleucid Empire

The Seleucid Empire was a Hellenistic state ruled by the Seleucid Dynasty, which existed from 312 BCE-63 BCE. It was founded by Seleucus I Nicator following the dissolution of Alexander the Great’s empire. Following Ptolemy’s successes in the Wars of the Diadochi, Seleucus, then a senior officer in the Macedonian Royal Army, received Babylonia. From there, he expanded his dominion to include much of Alexander’s near eastern territories. At the height of its power, the Seleucid Empire encompassed central Anatolia, Persia, the Levant, Mesopotamia, and what is now Kuwait, Afghanistan, and parts of Pakistan and Turkmenistan. Seleucus himself traveled as far as India in his campaigns. Seleucid expansion into Anatolia and Greece was halted, however, after decisive defeats at the hands of the Roman army.

The Seleucid Empire was a major center of Hellenistic culture, where Greek customs prevailed and the Greek political elite dominated, though mostly in urban areas. Existing Greek populations within the empire were supplemented with Greek immigrants.

The Kingdom of Pergamon

The ancient Greek city of Pergamon was taken by Lysimachus, King of Thrace, in 301 BCE, a short-lived possession that ended when the kingdom of Thrace collapsed. It became the capital of a new kingdom of Pergamon, which Philetaerus founded in 281 BCE, thus beginning the rule of the Attalid Dynasty. The Attalid kingdom began as a rump state, but was expanded by subsequent rulers. The Attalids themselves were some of the most loyal supporters of Rome in the Hellenistic world. Under Attalus I (r. 241-197 BCE), the Attalids allied with Rome against Philip V of Macedon, during the first and second Macedonian Wars. They allied with Rome again under Eumenes II (r. 197-158 BCE) against Perseus of Macedon, during the Third Macedonian War. Additionally, in exchange for their support against the Seleucids, the Attalids were given all former Seleucid domains in Asia Minor.

The Attalids were known for their intelligent and generous rule. Many historical documents from the era demonstrate that the Attalids supported the growth of towns by sending in skilled artisans and remitting taxes. They also allowed Greek cities to maintain nominal independence and sent gifts to Greek cultural sites, such as Delphi, Delos, and Athens, and even remodeled the Acropolis of Pergamon after the Acropolis in Athens. When Attalus III (r. 138-133 BCE) died without an heir, he bequeathed his entire kingdom to Rome to prevent civil war.

Macedon

Macedon, or Macedonia, was the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. In the partition of Alexander’s empire among the Diadochi, Macedon fell to the Antipatrid Dynasty, which was headed by Antipater and his son, Cassander. Following Cassander’s death in 297 BCE, Macedon slid into a long period of civil strife. Antigonus II (r. 277-239 BCE) successfully restored order and prosperity in the region, and established a stable monarchy under the Antigonid Dynasty, though he lost control of many Greek city-states in the process.

Notably, the Macedonian regime is the only successor state to Alexander the Great’s empire that maintained archaic perceptions of kingship, and elided the adoption of Hellenistic monarchical customs. The Macedonian king was never deified in the same way that kings of the Ptolemaic and Seleucid Dynasties had been. Additionally, the custom of proskynesis, a traditional Persian act of bowing or prostrating oneself before a person of higher social rank, was never adopted. Instead, Macedonian subjects addressed their kings in a far more casual manner, and kings still consulted with their aristocracy in the process of making decisions.

During the reigns of Philip V (r. 221-179 BCE) and his son Perseus (r. 179-168 BCE), Macedon clashed with the rising Roman republic. During the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE, Macedon fought a series of wars against Rome. Two decisive defeats in 197 and 168 BCE resulted in the deposition of the Antigonid Dynasty, and the dismantling of the kingdom of Macedon.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Rise of Macedon. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rise_of_Macedon. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Classical Greece: Rise of Macedon. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Classical_Greece#Rise_of_Macedon. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Epaminondas. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epaminondas. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Sarissa. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarissa. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Philip II of Macedon. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip_II_of_Macedon. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Filip_II_Macedonia.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Filip_II_Macedonia.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Makedonische_phalanx.png. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Makedonische_phalanx.png. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Phalanx. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phalanx. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Alexander the Great. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_the_great%23Character. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Alexander the Great. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Alexander_the_Great. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Filip_II_Macedonia.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Filip_II_Macedonia.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Makedonische_phalanx.png. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Makedonische_phalanx.png. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Alexander the Great. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_the_great%23mediaviewer/File:AlexanderTheGreat_Bust.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Alexander the Great. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_the_Great. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Filip_II_Macedonia.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Filip_II_Macedonia.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Makedonische_phalanx.png. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Makedonische_phalanx.png. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Alexander the Great. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_the_great%23mediaviewer/File:AlexanderTheGreat_Bust.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Alexander the Great. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_the_Great%23mediaviewer/File:Name_of_Alexander_the_Great_in_Hieroglyphs_circa_330_BCE.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Seleucid Empire. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seleucid_Empire. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Proskynesis. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proskynesis. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Pergamon. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pergamon. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Attalid dynasty. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Attalid_dynasty. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Macedonia (ancient kingdom). Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Macedonia_(ancient_kingdom). License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ptolemaic Kingdom. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ptolemaic_Kingdom. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Satrap. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Satrap. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Filip_II_Macedonia.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Filip_II_Macedonia.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Makedonische_phalanx.png. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Makedonische_phalanx.png. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Alexander the Great. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_the_great%23mediaviewer/File:AlexanderTheGreat_Bust.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Alexander the Great. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_the_Great%23mediaviewer/File:Name_of_Alexander_the_Great_in_Hieroglyphs_circa_330_BCE.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Map_Macedonia_336_BC-en.svg. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Map_Macedonia_336_BC-en.svg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Seleucid_Empire_28flat_map29.svg. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Seleucid_Empire_(flat_map).svg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ptolemy_I_Soter_Louvre_Ma849.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ptolemy_I_Soter_Louvre_Ma849.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Asia_Minor_188_BCE.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Asia_Minor_188_BCE.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright