1.2: The Problem with Checklist Approaches

- Page ID

- 98462

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

We've been doing research into why students fail to separate fact from fiction on the web.

What we've found? Students are bad at the web because they've been taught techniques that make them bad at it. And they've learned those those bad techniques from teachers.

Here's some things students often believe:

- They believe that .org's are more trustworthy than .com's.

- They believe that a good looking layout and few typos mean something is trustworthy.

- They think pages that have ads on them are less trustworthy than those that don't.

- They think that footnotes automatically make a site credible.

These are only a few of the (very wrong) things students believe. Before you learn to read the web you may have to unlearn some of the stuff you've been taught.

How Craap goes astray

Most instruction students get about reading the web is derived from a set of approaches called "checklist approaches".

Sometimes these approaches were presented as literal checklists. Above is a checklist for a methodology called CRAAP. (I'm not joking).

Sometimes they weren't checklists, but a set of "things to look for in a web page."

What the approaches had in common was this: you'd come to a webpage and look for signals that the page was trustworthy on the page itself. You'd ask questions like

- Does this look professional?

- Are there spelling errors?

- Is there scientific language?

- Does it use footnotes?

The "checklist" idea? Students were told the more "good" things the page had the more "trustworthy" it was.

Except there are three problems with this approach. Big problems.

Problem 1: The signals are meaningless

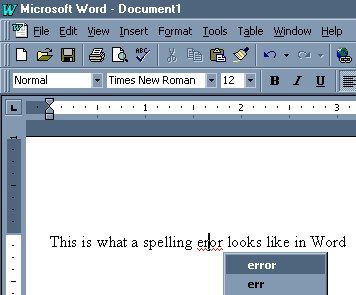

Picture of Word document with autocorrect

Most things people are told to look for? They're easy to fake. It's really cheap to get a good-looking site nowadays. You can be a disinformation agent from China or Russia and still use spell check. Anyone can add footnotes to make something look more serious (students do it all the time!) The same holds for using scientific language.

And a lot of things students are told to look for have no basis in reality at all. In our research we have found students believe

- .orgs are better than .coms (No.)

- non-profits are better than for-profits (Wrong.)

- Less ads on a page means the page is more reliable (Not even close.)

To put it simply — the things that might mean something are easy to fake, and many things students are taught to look for don't mean anything at all.

Problem 2: The checklist processes take too long

Checklist processes were developed for students trying to decide which of a number of library resources to use for a paper. Given that time frame, such an approach might make sense. You can spend 20 minutes looking at each of three journal articles you found to see which would be the best fit for an end of term research project.

In 2019, however, our problem is not deciding between three half-decent library resources over the course of an afternoon. Instead we are forced to sift through hundreds of possible search results and social media posts to try and determine whether each is worth our attention or belief.

Take this TikTok video, for example. In it, one user has made a video that complains about the discontinuation of plastic straws out of what she sees as too high a level of concern about turtles. It's a bit meanly expressed, but that's her point. Another user posts a reaction — by 2050 there will be more plastic in the ocean than fish.

It has literally taken me longer to explain this video than it takes you to watch it. But is the claim true? And what would happen if you had to engage in 20 minutes of investigation for every 10 second piece of content you viewed that made a claim?

Actually, we know what happens when students are given in-depth techniques to deal with the flood of content that reaches them — they don't use them. Without quick methods people decide to share content like this based on whether it seems believable, or worse, they just decide they can't trust anything at all.

The same is true with search. People use search to inform themselves about a variety of professional and civic issues. They search because they need to get information on a specific topic of pressing importance: how to safely change a tire, whether they should see a doctor about a rash, if the mayor's decision regarding panhandling will have a good or bad impact on the homelessness problem.

But the biggest gap is not whether they research deeply. It's whether they check at all. Take that factoid about plastic and 2050. If you could reliably check it in 60 seconds, you might. If not, you're either going to reject it or accept it without checking — mostly unconsciously. Without quick methods to search and sift, your "knowledge" about an issue will slowly become a mental shoebox of unverified scraps you heard here and there around the web.

While short methods may seem less rigorous, they are in fact better than long methods for many tasks. When I switch lanes while driving on the highway, I don't do a ten minute analysis of whether a car might be in the lane next to me. I check the mirror, do a head check, and change lanes. If my father had given me a ten minute lane-changing process when teaching me to drive, I wouldn't use it, and frequent accidents would just be a part of my life. This is the sort of thing you need for reading the web as well.

Problem 3: Using too many criteria results in stupid decisions

One popular idea is that checklists are important because they force students to evaluate dozens of criteria instead of just a few. But does evaluating more criteria result in better decisions? Many teachers say yes. The research says no.

The problem with having dozens of criteria is that many of them conflict. Readers then get overwhelmed, unsure to which ones they should pay the most attention. And that produces what I call the "sleazy car salesperson" effect.

Maybe you've had the good fortune to never have to deal with a car dealership. But the way it usually goes is this. You go in to get a car and you just want automatic braking, a rear camera, and satellite radio. What happens? Well, they've got a car that has all three, but it's also the luxury sedan and it's $8,000 more. You do get seat warmers and remote start, which are worth x hundred dollars, and the new side collision detection that's at least $1,000 as an after-market addition. Or you can get this other car that has two features but not the third, and if you add on the aftermarket cost it's less expensive than the luxury car, but you don't get that side collision detection, etc., etc. And... well, it's exhausting even to read that, right?

Car dealers set up cars this way intentionally, so that you can never weigh a couple factors in isolation, which leads to us being cognitively overwhelmed and making bad decisions. The effects of this sort of criteria overload are well-documented, going back decades. Yet methodologies like CRAAP set up processes in the same way.

On a pre-assessment we give to students, for example, we have students evaluate a statistical claim about firearm background checks. The sort of response we see repeatedly is, "Well, it's a .org so it's likely to be trustworthy, but it has an ad on the page so maybe not." It's this is "car lot" cognition. There's a tidal wave of conflicting signals so in the end we throw up our hands and say, "Who can know?"