The theatre at Pergamon could seat 10,000 people and was one of the steepest theatres in the ancient world. Like all Hellenic theatres, it was built into the hillside, which supported the structure and provided stadium seating that would have overlooked the ancient city and its surrounding countryside. The theatre is one example of the creation and use of dramatic and theatrical architecture.

The Gigantomachy

The Gigantomachy depicts the Olympian gods fighting against their predecessors the Giants (Titans), the children of the goddess Gaia. The frieze is known for its incredibly high relief, in which the figures are barely restrained by the wall, and for its deep drilling of lines with details to create dramatic shadows.

The high relief and deep drilling of the figures also increase the liveliness and naturalism of the scene. The figures are rendered with high plasticity. The texture of their skin, drapery, and scales add another level of naturalism. Furthermore, as the frieze follows the stairs, the limbs of the figures begin to spill out of their frame and onto the stairs, physically breaking into the space of the viewer. The style and high drama of the scenes are often referred to as the Hellenistic Baroque for its exaggerated motion, emphasis on details, and the liveliness of the characters.

The most famous scene on the frieze depicts Athena fighting the giant Alkyoneus. She grabs his head and pulls it back while Gaia emerges from the ground to plead for her son’s life and a winged Nike reaches over to crown Athena. Athena’s drapery swirls around her with deep folds and her whole body is nearly removed from the frieze. The figures are depicted with the heightened emotion commonly found on Hellenistic statues. Alkyoneus’s face strains in pain and Gaia’s eyes, which are all that remain of her face, are full of terror and sorrow at the death of her son.

The entire composition is depicted in a chiastic shape. Athena stretches out to grasps Alkoyneus’s head, the two figures pull at each other in opposite directions. Meanwhile, the figure of Nike moves diagonally towards Athena, showing their convergence in a moment of victory. The diagonal line created by Gaia mimics the shape of her son, connecting the two figures through line and pathos. The scene is filled with the tension and emotion that are key features in Hellenistic sculpture.

The Dying Gauls

A group of statues depicting dying Gauls, the defeated enemies of the Attalids, were situated inside the Altar of Zeus. The original set of statues is believed to have been cast in bronze by the court sculptor Epigonus in 230–220 BCE. Now only marble Roman copies of the figures remain.

Like the figures on the frieze and other Hellenistic sculptures, the figures are depicted with lifelike details and a high level of naturalism. They are also depicted in the common motif of barbarians. The men are nude and wear Celtic torcs. Their hair is shaggy and dishevelled. The figures are positioned in dramatic compositions and are shown dying heroically, which turns them into worthy adversaries, increasing the perception of the power of the Attalid dynasty. All three figures in the group are depicted in a Hellenistic manner. To fully appreciate the statues, it is best to walk around them. Their pain, nobility, and death are evident from all angles.

One Gaul is depicted lying down, supporting himself over his shield and a discarded trumpet. He furrows his brow as he looks downward at his bleeding chest wound as he prepares himself for death. His muscles are large and strong, signifying his strength as a warrior and implying the strength of the one who struck him down.

Two other figures complete the group. One figure depicts a Gallic chief committing suicide after he has killed his own wife. Also known as the Ludovisi Gaul, this sculpture group displays another heroic and noble deed of the foes, for typically women and children of the defeated would be murdered to avoid them from being captured and sold as slaves by the victors. The chief holds his fallen wife by the arm as he plunges his sword into his chest, where blood is already exiting the wound.

Sculpture in the Hellenistic Period

A key component of Hellenistic sculpture is the expression of a sculpture’s face and body to elicit an emotional response from the viewer. Hellenistic sculpture continues the trend of increasing naturalism seen in the stylistic development of Greek art. During this time, the rules of Classical art were pushed and abandoned in favour of new themes, genres, drama, and pathos that were never explored by previous Greek artists. Furthermore, the Greek artists added a new level of naturalism to their figures by adding elasticity to their form and expressions, both facial and physical. These figures interact with their audience in a new theatrical manner by eliciting an emotional reaction from their view—this is known as pathos.

Nike of Samothrace

One of the most iconic statues of the period, the Nike of Samothrace, also known as the Winged Victory (c. 190 BCE), commemorates a naval victory. This Parian marble statue depicts Nike, now armless and headless, alighting onto the prow of the ship. The prow is visible beneath her feet, and the scene is filled with theatricality and naturalism as the statue reacts to her surroundings.

Nike’s feet, legs, and body thrust forward in contradiction to her drapery and wings that stream backwards. Her clothing whips around her from the wind and her wings lift upwards. This depiction provides the impression that she has just landed and that this is the precise moment that she is settling onto the ship’s prow. In addition to the sculpting, the figure was most likely set within a fountain, creating a theatrical setting where both the imagery and the auditory effect of the fountain would create a striking image of action and triumph.

Venus de Milo

Also known as the Aphrodite of Melos (c. 130–100 BCE), this sculpture by Alexandros of Antioch, is another well-known icon of the Hellenistic period. Today the goddess’s arms are missing. It has been suggested that one arm clutched at her slipping drapery while the other arm held out an apple, an allusion to the Judgment of Paris and the abduction of Helen.

Originally, like all Greek sculptures, the statue would have been painted and adorned with metal jewelry, which is evident from the attachment holes. This image is in some ways similar to Praxitiles’ Late Classical sculpture Aphrodite of Knidos (fourth century BCE), but it is considered to be more erotic than its earlier counterpart. For instance, while she is covered below the waist, Aphrodite makes little attempt to cover herself. She appears to be teasing and ignoring her viewer, instead of accosting him and making eye contact.

Altered States

While the Nike of Samothrace exudes a sense of drama and the Venus de Milo a new level of feminine sexuality, other Greek sculptors explored new states of being. Instead of reproducing images of the ideal Greek male or female, as was favoured during the Classical period, sculptors began to depict images of the old, tired, sleeping, and drunk—none of which are ideal representations of a man or woman.

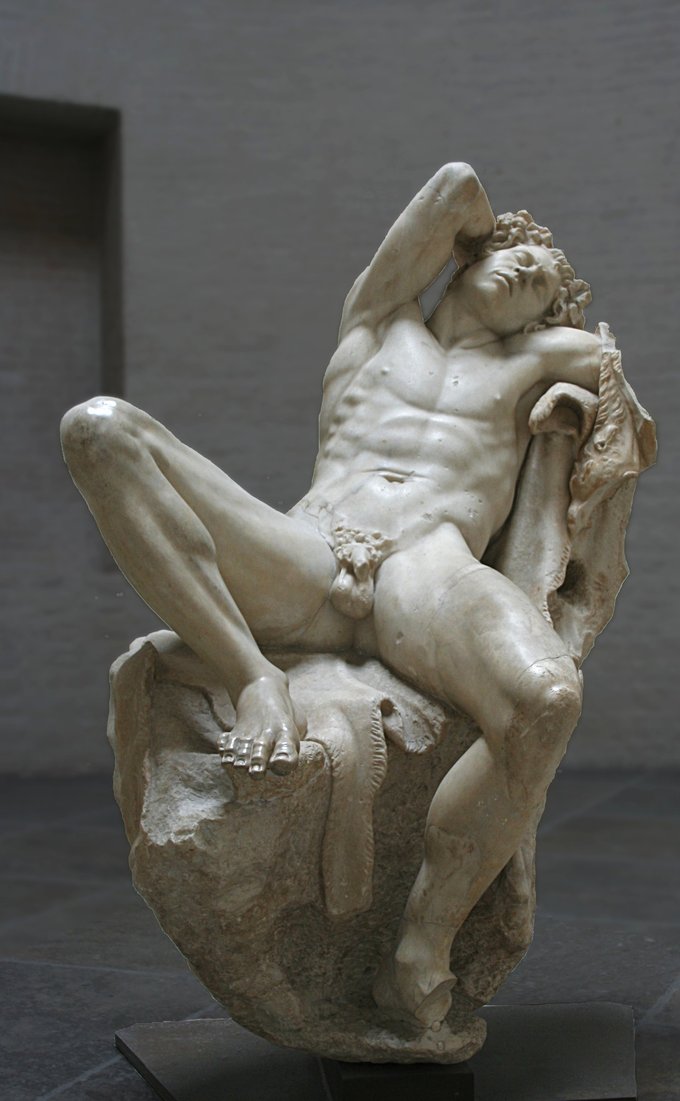

The Barberini Faun

The Barberini Faun, also known as the Sleeping Satyr (c. 220 BCE), depicts an effeminate figure, most likely a satyr, drunk and passed out on a rock. His body splays across the rock face without regard to modesty. He appears to have fallen to sleep in the midst of drunken revelry and he sleeps restlessly, his brow is knotted, face worried, and his limbs are tense and stiff. Unlike earlier depicts of nude men, but in a similar manner to the Venus de Milo, the Barberini Faun seems to exude sexuality.

Drunken Old Woman

Images of drunkenness were also created of women, which can be seen in a statue attributed to the Hellenistic artist Myron of a drunken beggar woman. This woman sits on the floor with her arms and legs wrapped around a large jug and a hand gripping the jug’s neck. Grapevines decorating the top of the jug make it clear that it holds wine. The woman’s face, instead of being expressionless, is turned upward and she appears to be calling out, possibly to passersby. Not only is she intoxicated, but she is old: deep wrinkles line her face, her eyes are sunken, and her bones stick out through her skin.

Seated Boxer

Another image of the old and weary is a bronze statue of a seated boxer. While the image of an athlete is a common theme in Greek art, this bronze presents a Hellenistic twist. He is old and tired, much like the Late Classical image of a Weary Herakles. However, unlike Herakles, the boxer is depicted as beaten and exhausted from his pursuit. His face is swollen, lip spilt, and ears cauliflowered. This is not an image of a heroic, young athlete but rather an old, defeated man many years past his prime.

Portraiture

Individual portraits, instead of idealization, also became popular during the Hellenistic period. A portrait of Demosthenes by Polyeuktos (280 BCE) is not an idealization of the Athenian statesman and orator. Instead, the statue takes notes of Demosthenes’s characteristic features, including his overbite, furrowed brow, stooped shoulders, and old, loose skin. Even portrait busts, often copied from Polyeuktos’ famed statue, depict the weariness and sorrow of a man despairing the conquest of Philip II and the end of Athenian democracy.

Roman Patronage

The Greek peninsula fell to Roman power in 146 BCE. Greece was a key province of the Roman Empire, and Roman interest in Greek culture helped to circulate Greek art around the empire, especially in Italy, during the Hellenistic period and into the Imperial period of Roman hegemony.

Greek sculptors were in high demand throughout the remaining territories of Alexander’s empire and then throughout the Roman Empire. Famous Greek statues were copied and replicated for wealthy Roman patricians and Greek artists were commissioned for large-scale sculptures in the Hellenistic style. Originally cast in bronze, many Greek sculptures that we have today survive only as marble Roman copies. Some of the most famous colossal marble groups were sculpted in the Hellenistic style for wealthy Roman patrons and for the imperial court. Despite their Roman audience, these were purposely created in the Greek style and continued to display the drama, tension, and pathos of Hellenistic art.

Laocoön and His Sons

Laocoön was a Trojan priest of Poseidon who warned the Trojans, “Beware of Greeks bearing gifts,” when the Greeks left a large wooden horse at the gates of Troy. Athena or Poseidon (depending on the story’s version), upset by his vain warning to his people, sent two sea serpents to torture and kill the priest and his two sons. Laocoön and His Sons, a Hellenistic marble sculpture group (attributed by the Roman historian Pliny the Elder to the sculptors Agesander, Athenodoros, and Polydorus from the island of Rhodes) were created in the early first century CE to depict this scene from Virgil’s epic, The Aeneid.

Similar to other examples of Hellenistic sculpture, Laocoön and His Sons depicts a chiastic scene filled with drama, tension, and pathos. The figures writhe as they are caught in the coils of the serpents. The faces of the three men are filled with agony and toil, which is reflected in the tension and strain of their muscles. Laocoön stretches out in a long diagonal from his right arm to his left as he attempts to free himself. His sons are also entangled by the serpents, and their faces react to their doom with confusion and despair. The carving and detail, the attention to the musculature of the body, and the deep drilling, seen in Laocoön’s hair and beard, are all characteristic elements of the Hellenistic style.

Farnese Bull

The Farnese Bull (c. 200–180 BCE), named for the patrician Roman family who owned the statue in the Italian Renaissance, is believed to have been created for the collection of Asinius Pollio, a Roman patrician. Pliny the Elder attributes the statue to the artists and brothers Apollonius and Tauriscus of Tralles, Rhodes.

The colossal marble statue, carved from a single block of marble, depicts the myth of Dirce, the wife of the King of Thebes, who was tied to a bull by the sons of Antiope to punish her for mistreating their mother. The composition is large and dramatic and demands the viewer to encircle it in order to view and appreciate the narrative and pathos from all angles. The various angles reveal different expressions, from the terror of Dirce, to the determination of Antiope’s sons, to the savagery of the bull.

- Hellenistic architecture, in a manner similar to Hellenistic sculpture, focuses on theatricality, drama, and the experience of the viewer. Public spaces and temples were created with the people in mind, and so were built on a new, monumental scale.

- Stoas are colonnaded porticos used to define public space and protect patrons from the elements. Stoas are often found around a city’s agora, and turn the city’s central place for civic, administrative, and market elements into a grand space.

- The Corinthian order, developed during the Classical period, witnessed increased popularity during the Hellenistic period. The columnar style of the order is similar in many ways to the Ionic order except for the column’s capital, which is vegetal and lush. A double layer of acanthus leaves lines the basket from which stylized tendrils and volutes emerge.

- Pergamon was the capital city of the Kingdom of Pergamon, which was ruled by the Attalids in the centuries following the death of Alexander the Great.

- The Acropolis of Pergamon is famous for its monumental architecture. Most of the buildings command a great view of the surrounding countryside and together create a dramatic public space.

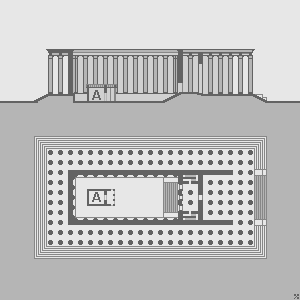

- The Altar of Zeus at Pergamon was a monumental u-shaped Ionic building that stood on a high platform and was accessed by a wide set of stairs. Besides its dramatic architecture, the altar is known for its Gigantomachy frieze and sculptures of defeated Gauls.

- Hellenistic sculpture takes the naturalism of the body’s form and expression to a level of hyper-realism where the expression of the sculpture’s face and body elicit an emotional response.

- Drama and pathos are new factors in Hellenistic sculpture. The style of the sculpting is no longer idealized. Rather, they are often exaggerated, and details are emphasized to add a new, heightened level of motion and pathos.

- New compositions and states of mind are explored in Hellenistic sculptures including old age, drunkenness, sleep, agony, and despair.

- Portraiture became popular in this period. The subjects are depicted with a sense of naturalism that displays their imperfections.

- Hellenistic sculpture was in especially high demand after the Greek peninsula fell to the Romans in 146 BCE. Notable sculptures produced for Roman patrons include Laocoön and His Sons and the Farnese Bull.

Adapted from “Boundless Art History” https://courses.lumenlearning.com/bo...nistic-period/ License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike