The Trial of Neaira: Annotated with a Critical Introduction and Questions

- Page ID

- 82581

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The Trial of Neaira

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Phryne revealed before the Areopagus (1861), Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons. The courtesan Phyrne had been accused of profaning the Eleusinian mysteries by letting down her hair and wading, naked, into the sea (presumably in allusion to the origins of Aphrodite, goddess of love). According to legend, when it appeared that the jury would condemn Phyrne, her male advocate, Hypereides, disrobed her before the Areopagite court, which then found in her favor.

Background for the Trial of Neaira [neh-EYE-ruh]

All information is drawn from Debra Hamel, Trying Neaira: The True Story of a Courtesan's Scandalous Life in Ancient Greece (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005), unless otherwise cited.

What is the nature of this text?

It is one of about one hundred speeches delivered in Athens’s law courts which had survived. Speech-writers composed speeches for themselves and others to deliver in court or the Athenian assembly. Although attributed to Demosthenes, the speech “Against Neaira” was probably composed and certainly delivered by Apollodorus. Those bringing cases in courts, both prosecutors and defenders, often deliberately misrepresented information or lied to sway the jurors, even when it came to describing the laws the jury was supposed to enforce. There were no professional juries or judges in Athens.

Who was Neaira?

Neaira was a foreigner (metic), an immigrant to Athens from Megara (although she was born in Corinth, a port city). She would have spoken Doric Greek, not Attic Greek and would have sounded as if she had an ‘accent’ to Athenians. When brought to trial (c. 343-340 BCE), she was fifty-something. She had been sold as a child to the keeper of a brothel in Corinth, but eventually won her freedom and had married Stephanos, a citizen of Athens. It was this relationship that was under attack by Apollodorus. It was illegal for Athenian citizens to formally marry non-citizens, although other relationships were tolerated (lover, mistress, customer, prostitute). Apollodorus brought Stephanos and Neaira to trial and, if convicted, Neaira would have faced re-enslavement and Stephanos a heavy fine. The case was the product of a long-standing feud between the two men; Apollodorus saw an attack on Neiara as a way to punish Stephanos.

Neaira appears to have been born around 400-395 BCE and was sold to a brothel-keeper Nikarete (a former slave herself), who appears to have kept several girls at a time, some of whom were mentioned by name in Philetairos’ play, The Huntress, written in the early 360s BCE. In ancient Greece, prostitution was common, legal, and regulated, particularly in port-towns and cities. Prostitutes occupied a range of statuses. Streetwalkers (pornai) were often slaves and/or foreigners imported from “barbarian” (non Greek-speaking) cultures. They wore heavy makeup, distinctive clothing, and frequented red-light districts with convenient alley-ways. Others worked out of whorehouses where the workers displayed themselves semi-naked and catcalled to customers from windows and roofs (the opposite of how respectable women were meant to behave). Pornai charged customers by the service and/or position assumed, and prices ranged between 1/9 and ⅔ of a skilled worker’s daily wage.

Auletrides, very often slaves, were hired to play music on the aulos at symposia or drinking parties where males were entertained by “flute-girls,” young male flute-players, and courtesans (hetairai). Plato’s symposium was exceptional in that the flute-girls were dismissed after performing music and the male guests indulged in conversation. Other accounts of symposia suggest a more raucous atmosphere with entertainment by musicians and acrobats of both genders. It was generally assumed that the entertainers were available for sex. Athens had regulations for this group of workers as well, female musicians were not to be paid more than two drachmas per evening. Ten officials, the astynomoi, were responsible for ensuring customers did not bicker over the same girl. If more than one man was interested in hiring an individual player, the competitors were to draw lots and the winner could hire her. It may be that the players earned extra for services beyond musical entertainment.

Brygos Painter, Red-figured cup from Athens, c. 490-480 BCE, ceramic, British Museum, London, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. A male guest at a symposium watches a girl (possibly a slave) dance for his entertainment.

Nikias painter, Symposium scene: banqueters playing the kottabos game while a girl plays the aulos, Attic red-figure bell-krater, c. 420 BCE, National Archaeological Museum, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

At the expensive end of the spectrum were hetairai or “female companions,” who were paid by the period of time they kept the customer company, as much as ten drachmas per evening for conversation, musical performance, and potentially sex. Similar to geisha in Japan, euphemistic language and gift/favor exchange were the rule. The famous courtesan Theodote supposedly said: “If someone has become my friend and wants to treat me well, he is my livelihood.” Unlike pornai, highly successful hetairai could choose their customers and how many favors they wished to bestow.

A man and a courtesan reclining on a bench during a banquet; Tondo from an Attic red-figure kylix, circa 490 BC. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Men, women, and sex in Ancient Greece:

There were few avenues for sex outside of marriage in ancient Greece. Most Athenian men did not marry until they were nearly thirty and relations with free women were rigidly restricted. Male adulterers and rapists could be legally killed if caught in the act. Female adulteresses and/or prostitutes could not marry or participate in public religious ceremonies. Prostitution involved both sexes differently; women of all ages and young men were sex workers and served a mostly male clientele. Prostitution was legal and in Athens, was taxed by the state. Unmarried Athenian men could take a male lover, visit prostitutes, or avail themselves of the slaves of their household (with or without those slaves’s consent).

Attic red figure cup depicting hetairai and youths, Fitzwilliam Museum, Creative Commons via Wikimedia Commons.

Poorer free women worked in shops and selling in the marketplace. However, respectable and well-to-do free women were meant to remain at home, oversee the household slaves, engage in textile production (spinning, weaving, embroidery), and bear children. Spartan women were exceptions. When men who were not members of the household visited for business or dinner, free women were expected to sequester themselves in the women’s quarters. However, women did leave their homes for religious festivals and funerals and to visit neighbors. Women could be wooed by gaining access to their slaves. At least one adulterer succeeded. The orator Lysias’s On the Murder of Eratosthenes, describes the case of a woman seen at a funeral by Eratosthenes, who gained access to her slave girl and the two conducted an affair while her husband was in another portion of the house. The enraged husband discovered the two lovers and delivered the speech defending himself against the charge of murdering Eratosthenes in flagrante (caught in the act).

Lysias:

The orator Lysias was a customer of Metaneira, Neaira’s fellow hetaira, also owned by Nikarete. Lysias was a metic or free foreigner who lived in Athens. After Athens surrendered to Sparta in 404, Sparta installed the “thirty tyrants” in Athens, who promptly began executing prominent individuals and seizing their assets. Lysias brought one of them to trial circa 403 BCE for extorting and stealing money from him, forcing his brother to commit suicide, and seizing hard assets from himself and his brother, including slaves. Lysias would assist the overthrow of the Thirty and restoration of democracy, and became a well-known speech-writer for those appearing in court. Lysias brought Metaneira and Neaira to Athens for the Eleusinian mysteries, a nearly week-long festival in honor of the goddess Demeter. Neaira would visit Athens again with Nikarete to attend the Great Panathenaia, a festival celebrated in honor of Athena. People flocked to Athens to see contests in music, chariot races, foot-races, dancing, sacrifices, and a sacred procession to the Acropolis to present the image of Athena with a new robe. It appears that Neaira had formed some kind of relationship with Simos of Thessaly, a member of a leading aristocratic family in Thessaly. Neaira and others of Nikarete’s slave girls appear to have been in high demand as companions and entertainers as well as prostitutes, but we ought to remember that as a slave, Neaira would not have had the choice of clients that free and famous hetairai enjoyed.

At a certain point, Nikarete decided that Neaira was at her sell-by date and she was purchased by two of her long-time customers, Timanoridas of Corinth and Eukrates of Leukas. The two men paid 3000 drachmas for Neaira (an average slave cost about 300-600 drachmas). There appears to have been no friction generated by the arrangement. After one or both of the men were preparing to get married, the two men offered Neaira the chance to purchase her freedom for 2000 drachmas on the condition that she not stay in Corinth. This is where the even more interesting period of Neaira’s life began.

Reading Questions:

Read the Trial of Neaira and do your best to answer the following questions.

1. How did one achieve and lose citizenship in Athens and what was the status of foreigners (metics) and slaves in Athens?

2. Theomnestus actually opens the case: what is his relationship to Apollodorus? What is the back-history between the accusing parties and Stephanos?

3. What is Theomnestus actually trying to do in his speech? Who is he targeting and why?

4. What do the earlier lawsuits between Stephanos and Apollodorus tell us about Athenian society’s attitudes towards government, citizens, slaves, and women? (see, for example, sections 6-8, 9-10).

5. What cases and charges did Apollodorus bring and did he provide convincing proof (sections 16 and following)?

6. What do we learn of the life of a courtesan? (sectionss 18-48, 107-117)?

7. What does the fact that some of Neaira’s former clients came to Corinth to help her buy her freedom say about the nature of their relationships, particularly Phrynion? What impression of Phrynion do we get from Apollodorus’ speech? (sections 30, 33)

8. What did Neaira stand to gain from her relationship with Stephanos, according to Apollodorus? What did Stephanos stand to gain? What property did he possess? (sections 39, 50, 65)

9. What is a sycophant? (sections 26-7, 43)

10. What were common penalties inflicted on men caught in the act of adultery in Athens? (section 41)

11. How does Phrynion behave towards Neaira and why? (section 40) How does Stephanos come to her defence and what is the result? (sections 40, 46, 48)

12. What is the story of “Neiara’s” daughter Phano and her son? (sections 50-61) What do we learn of Athenian marriage, divorce, and inheritance laws from Phano’s and Phrastor’s marriage?

13. What does Stephanos’ conduct when finding Epainetos in flagrante with Phano in his household tell us about Athenian attitudes towards sex? (sections 64-5) What interpretation does Apollodorus try to put on the episode and why? (sections 65-70) What did Stephanos and Epainetos stand to lose or gain?

14. What do we learn about Athenian society from Phano’s second marriage? (sectionss 72-5, 80-3, 85-7)

15. Apollodorus’ imagined reaction of the Athenian wives, daughters, and mothers of the jurors is an interesting male projection of attitudes on the women of Athenian citizens? What does he imagine the female reaction would be and why does he depict their reaction in the way he does (sections 110 and following)? Did Athenian women have an investment in preserving the distinction between citizen and metic? Wife and courtesan?

16. What do we learn of Stephanos’ and Neaira’s relationship? (sections 118-25)?

17. Why do Stephanos and Neaira refuse to hand their slaves over for torture (sections 120 and following)?

The Trial of Neaira, more commonly known as Demosthenes [really Apollodorus], Against Neaira:

This translation is adapted from Demosthenes with an English translation, by Norman W. and Norman J. DeWitt (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1949). I have altered some terms and the spelling of some names.

[1] Many indeed are the reasons, men of Athens [1], which urged me to prefer this indictment against Neaira, and to come before you. We have suffered grievous wrongs at the hands of Stephanus and have been brought by him into the most extreme peril, I mean my father-in-law, myself, my sister, and my wife; so that I shall enter upon this trial, not as an aggressor, but as one seeking vengeance. For Stephanus was the one who began our quarrel without ever having been wronged by us in word or deed. I wish at the outset to state before you the wrongs which we have suffered at his hands, in order that you may feel more indulgence for me as I seek to defend myself and to show you into what extreme danger we were brought by him of losing our country and our civic rights.

[2] When the people of Athens passed a decree granting the right of citizenship [2] to Pasion and his descendants on account of services to the state, my father favored the granting of the people's gift, and himself gave in marriage to Apollodorus, son of Pasion, [3] his own daughter, my sister, and she is the mother of the children of Apollodorus. Inasmuch as Apollodorus acted honorably toward my sister and toward all of us, and considered us in truth his relatives and entitled to share in all that he had, I took to wife his daughter, my own niece.

[3] After some time had elapsed Apollodorus was chosen by lot as a member of the senate [4]; and when he had passed the scrutiny and had sworn the customary oath, there came upon the city a war and a crisis so grave that, if victors, you would be supreme among the Greek peoples, and would beyond possibility of dispute have recovered your own possessions and have crushed Philip [of Macedon] in war; but, if your help arrived too late and you abandoned your allies, allowing your army to be disbanded for want of money, you would lose these allies, forfeit the confidence of the rest of the Greeks, and risk the loss of your other possessions, Lemnos [5] and Imbros [6], and Scyros [7] and the Chersonese [8].

[4] You were at that time on the point of sending your entire force to Euboea [9] and Olynthus [10], and Apollodorus, being one of its members, brought forward in the senate a bill, and carried it as a preliminary decree to the assembly, proposing that the people should decide whether the funds remaining over from the state's expenditure should be used for military purposes or for public spectacles. For the laws prescribed that, when there was war, the funds remaining over from state expenditures should be devoted to military purposes, and Apollodorus believed that the people ought to have power to do what they pleased with their own; and he had sworn that, as member of the senate, he would act for the best interests of the Athenian people, as you all bore witness at that crisis.

[5] For when the division took place there was not a man whose vote opposed the use of these funds for military purposes; and even now, if the matter is anywhere spoken of, it is acknowledged by all that Apollodorus gave the best advice, and was unjustly treated. It is, therefore, upon the one who by his arguments deceived the jurors that your wrath should fall, not upon those who were deceived.

[6] This fellow Stephanus indicted the decree as illegal, and came before a court. He produced false witnesses to substantiate the slanderous charge that Apollodorus had been a debtor to the treasury for twenty-five years, and by making all sorts of accusations that were foreign to the indictment won a verdict against the decree. So far as this is concerned, if he saw fit to follow this course, we do not take it ill; but when the jurors were casting their votes to fix the penalty, although we begged him to make concessions, he would not listen to us, but fixed the fine at fifteen talents in order to deprive Apollodorus and his children of their civic rights, and to bring my sister and all of us into the most extreme distress and utter destitution.

[7] For the property of Apollodorus did not amount to as much as three talents [11] to enable him to pay in full a fine of such magnitude, yet if it were not paid by the ninth prytany [12] the fine would have been doubled and Apollodorus would have been inscribed as owing thirty talents to the treasury, all the property that he has would have been scheduled as belonging to the state, and upon its being sold Apollodorus himself and his children and his wife and all of us would have been reduced to the most extreme distress.

[8] And more than this, his other daughter would never have been given in marriage; for who would ever have taken to wife a portionless [13] girl from a father who was a debtor to the treasury and without resources? Of such magnitude, you see, were the calamities which Stephanus was bringing upon us all without ever having been wronged by us in any respect. To the jurors, therefore, who at that time decided the matter I am deeply grateful for this at least, that they did not suffer Apollodorus to be utterly ruined, but fixed the amount of the fine at one talent, so that he was able to discharge the debt, although with difficulty. With good reason, then, have we undertaken to pay Stephanus back in the same coin.

[9] For not only did Stephanus seek in this way to bring us to ruin, but he even wished to drive Apollodorus from his country. He brought a false charge against him that, having once gone to Aphidna [14] in search of a runaway slave of his, he had there struck a woman, and that she had died of the blow; and he suborned some slaves and got them to give out that they were men of Cyren [15], and by public proclamation cited Apollodorus before the court of the Palladium on a charge of murder.

[10] This fellow Stephanus prosecuted the case, declaring on oath that Apollodorus had killed the woman with his own hand, and he imprecated destruction upon himself and his race and his house, affirming matters which had never taken place, which he had never seen or heard from any human being. However, since he was proved to have committed perjury and to have brought forward a false accusation, and was shown to have been hired by Cephisophon and Apollophanes to procure for pay the banishment or the disenfranchisement [16] of Apollodorus, he received but a few votes out of a total of five hundred, and left the court a perjured man and one with the reputation of a scoundrel.

[11] Now, men of the jury, I would have you ask yourselves, considering in your own minds the natural course of events, what I could have done with myself and my wife and my sister, if it had fallen to the lot of Apollodorus to suffer any of the injuries which this fellow Stephanus plotted to inflict upon him in either the former or the latter trial, or how great were the disgrace and the ruin in which I should have been involved.

[12] People came to me privately from all sides encouraging me to exact punishment from my opponent for the wrongs he had done us. They flung in my teeth the charge that I was the most cowardly of humankind, if, being so closely related to them, I did not take vengeance for the injuries done my sister, my father-in-law, my sister's children, and my own wife, and if I did not bring before you this woman who is guilty of such offensive impiety toward the gods, of such outrage toward the commonwealth, and of such contempt for your laws, and by prosecuting her and by my arguments convicting her of crime, to enable you to deal with her as you might see fit.

[13] And as Stephanus here sought to deprive me of my relatives contrary to your laws and your decrees, so I too have come before you to prove that Stephanus is living with an alien [17] woman contrary to the law; that he has introduced children not his own to his fellow clans-men and demes-men [18]; that he has given in marriage the daughters of courtesans as though they were his own; that he is guilty of impiety toward the gods [19]; and that he nullifies the right of your people to bestow its own favors, if it chooses to admit anyone to citizenship; for who will any longer seek to win this reward from you and to undergo heavy expense and much trouble in order to become a citizen, when he can get what he wants from Stephanus at less expense, assuming that the result for him is to be the same?

[14] The injuries, then, which I have suffered at the hands of Stephanus, and which led me to prefer this indictment, I have told you. I must now prove to you that this woman Neaira [20] is an alien, that she is living with this man Stephanus as his wife, and that she has violated the laws of the state in many ways. I make of you, therefore, men of the jury, a request which seems to me a proper one for a young man and one without experience in speaking—that you will permit me to call Apollodorus as an advocate to assist me in this trial.

[15] For he is older than I and is better acquainted with the laws. He has studied all these matters with the greatest care, and he too has been wronged by this fellow Stephanus so that no one can object to his seeking vengeance upon the one who injured him without provocation. It is your duty, in the light of truth itself, when you have heard the exact nature both of the accusation and the defense, then and not till then to reach a verdict which will be in the interest of the gods of the laws, of justice, and of your own selves.

[16] The wrongs done to me by Stephanus, men of Athens, which have led me to come forward to accuse this woman Neaira, have been told you by Theomnestus. And that Neaira is an alien woman and is living as his wife with Stephanus contrary to the laws, I wish to make clear to you. First, the clerk shall read you the law under which Theomnestus preferred this indictment and this case comes before you.

Law: “If an alien shall live as a husband with an Athenian woman in any way or manner whatsoever, he may be indicted before the Thesmothetae by anyone who chooses to do so from among the Athenians having the right to bring charges. And if he is convicted, he shall be sold, himself and his property, and the third part shall belong to the one securing his conviction. The same principle shall hold also if an alien woman shall live as a wife with an Athenian, and the Athenian who lives as a husband with the alien woman so convicted shall be fined one thousand drachmae [21].”

[17] You have heard the law, men of the jury, which forbids the union of an alien woman with an Athenian, or of an Athenian woman with an alien in any way or manner whatsoever, or the procreation of children. And if any person shall transgress this law, it has provided that there shall be an indictment against them before the Thesmothetae, against both the alien man and the alien woman, and that, if convicted, any such person shall be sold. I wish, therefore, to prove to you convincingly from the very beginning that this woman Neaira is an alien.

[18] There were these seven girls who were purchased while they were small children by Nikarete, who was the freedwoman [22] of Charisius the Elean and the wife of his cook Hippias. She was skilled in recognizing the budding beauty of young girls and knew well how to bring them up and train them artfully; for she made this her profession, and she got her livelihood from the girls.

Statue of a young girl, marble, 300 - 275 BCE, Archaeological Museum of Brauron, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

[19] She called them by the name of daughters in order that, by giving out that they were free women, she might exact the largest fees from those who wished to enjoy them. When she had reaped the profit of the youthful prime of each, she sold them, all seven, without omitting one—Anteia and Stratola and Aristocleia and Metaneira and Phila and Isthmias and this Neaira.

[20] Who it was who purchased them severally, and how they were set free by those who bought them from Nikarete, I will tell you in the course of my speech, if you care to hear and if the water in the water-clock holds out. I wish for the moment to return to the defendant Neaira, and prove to you that she belonged to Nikarete, and that she lived as a prostitute letting out her person for hire to those who wished to enjoy her.

[21] Lysias, the sophist [23], as the lover of Metaneira, wished, in addition to the other expenditures which he lavished upon her, also to initiate her; for he considered that everything else which he expended upon her was being taken by the woman who owned her, but that from whatever he might spend on her behalf for the festival and the initiation the girl herself would profit and be grateful to him. So he asked Nikarete to come to the [Eleusinian] mysteries bringing with her Metaneira that she might be initiated, and he promised that he would himself initiate her.

A votive plaque known as the Ninnion Tablet, depicting elements of the Eleusinian Mysteries, discovered in the sanctuary at Eleusis (mid-4th century BCE)

[22] When they got here, Lysias did not bring them to his own house, out of regard for his wife, the daughter of Brachyllus and his own niece, and for his own mother, who was elderly and who lived in the same house; but he lodged the two, Metaneira and Nikarete, with Philostratus of Colonus, who was a friend of his and was as yet unmarried. They were accompanied by this woman Neaira, who had already taken up the trade of a prostitute, young as she was; for she was not yet old enough.

[23] To prove the truth of my statements—that the defendant belonged to Nikarete and followed in her train, and that she prostituted her person to anyone who wished to pay for it—I will call Philostratus as a witness to these facts.

Deposition: “Philostratus, son of Dionysius, of Colonus, deposes that he knows that Neaira was a slave of Nikarete, to whom Metaneira also belonged, that they were residents of Corinth, and that they stayed at his house when they came to Athens for the mysteries, and that Lysias the son of Cephalêus, who was an intimate friend of his, established them in his house.”

[24] Again after this, men of Athens, Simus the Thessalian came here with the defendant Neaira for the great Panathenaea. Nikarete came with her, and they lodged with Ctesippus son of Glauconides,of Cydantidae; and the defendant Neaira drank and dined with them in the presence of many men, as any courtesan would do. To prove the truth of my statements, I will call witnesses to these facts.

[25] Please call Euphiletus, son of Simon, of Aexonê, and Aristomachus, son of Critodemus, of Alopecê. Witness statement: “Euphiletus son of Simon, of Aexonê, and Aristomachus son of Critodemus, of Alopecê, depose that they know that Simus the Thessalian came to Athens for the great Panathenaea, and that Nikarete came with him, and Neaira, the present defendant; and that they lodged with Ctesippus son of Glauconides, and that Neaira drank with them as being a courtesan, while many others were present and joined in the drinking in the house of Ctesippus.”

Courtesans drinking at a symposium. From Hetären aus Baumeister: Denkmäler des klassischen Altertums (1885) vol. 1, p. 365. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

[26] After this, you must know, she plied her trade openly in Corinth [24] and was quite a celebrity, having among other lovers Xenocleides the poet, and Hipparchus the actor, who kept her on hire. To prove the truth of my statement I cannot bring before you the testimony of Xenocleides, since the laws do not permit him to testify.

[27] For when on the advice of Callistratus you undertook to aid the Lacedaemonians [Spartans] (369 BCE), he at that time opposed in the assembly the vote to do so, because he had purchased the right to collect the two per cent tax on grain during the peace, and was obliged to deposit his collections in the senate-chamber during each prytany. For this he was entitled to exemption under the laws and did not go out on that expedition; but he was indicted by this man Stephanus for avoidance of military duty, and being slanderously maligned in the latter's speech before the court, was convicted and deprived of his civic rights.

[28] And yet do you not count it a monstrous thing that this Stephanus has taken the right of free speech from those who are native-born citizens and are lawful members of our commonwealth, and in defiance of all the laws forces upon you as Athenians those who have no such right? I will, however, call Hipparchus himself and force him either to give testimony or take the oath of disclaimer, or I will subpoena him. Please call Hipparchus.

Deposition: “Hipparchus of Athmonon deposes that Xenocleides and he hired in Corinth Neaira, the present defendant, as a courtesan who prostituted herself for money, and that Neaira used to drink at Corinth in the company of himself and Xenocleides the poet.”

[29] After this, then, she had two lovers, Timanoridas the Corinthian and Eucrates the Leucadian [25]. These men seeing that Nikarete was extravagant in the sums she exacted from them, for she demanded that they should supply the entire daily expenses of the household, paid down to Nikarete thirty minae [26] as the price of Neaira's person, and purchased the girl outright from her in accordance with the law of the city, to be their slave.

[30] And they kept her and made use of her as long a time as they pleased. When, however, they were about to marry, they gave her notice that they did not want to see her, who had been their own mistress, plying her trade in Corinth or living under the control of a brothel-keeper; but that they would be glad to recover from her less than they had paid down, and to see her reaping some advantage for herself. They offered, therefore, to remit one thousand drachmae toward the price of her freedom, five hundred drachmae apiece; and they bade her, when she found the means, to pay them the twenty minae. When she heard this proposal from Eucrates and Timanoridas, she summoned to Corinth, among others who had been her lovers, Phrynion of Paeania, the son of Demon and the brother of Demochares, a man who was living a licentious and extravagant life, as the older ones among you remember.

[31] When Phrynion came to her, she told him the proposal which Eucrates and Timanoridas had made to her, and gave him the money which she had collected from her other lovers as a contribution toward the price of her freedom, and added whatever she had gained for herself, and she begged him to advance the balance needed to make up the twenty minae, and to pay it to Eucrates and Timanoridas to secure her freedom.

[32] He listened gladly to these words of hers, and taking the money which had been paid in to her by her other lovers added the balance himself and paid the twenty minae as the price of her freedom to Eucrates and Timanoridas on the condition that she should not ply her trade in Corinth. To prove that these statements of mine are true, I will call as witness to them the man who was present. Please call Philagrus of Melitê.

Deposition: “Philagrus of Melitê deposes that he was present in Corinth when Phrynion, the brother of Demochares, paid down twenty minae as the price of Neaira, the present defendant, to Timanoridas, the Corinthian, and Eucrates, the Leucadian; and that after paying down the money Phrynion went off to Athens, taking Neaira with him.”

[33] When he came back here, bringing her with him, he treated her without decency or restraint, taking her everywhere with him to dinners where there was drinking and making her a partner in his revels; and he had intercourse with her openly whenever and wherever he wished, making his privilege a display to the onlookers. He took her to many houses to raucous parties and among them to that of Chabrias of Aexonê, when, in the archonship of Socratidas (373 BCE), he was the victor at the Pythian games [27] with the four-horse chariot which he had bought from the sons of Mitys, the Argive [28], and returning from Delphi [29] he gave a feast at Colias [at the temple of Athena [30] Colias], to celebrate his victory, and in that place many had intercourse with her when she was drunk, while Phrynion was asleep, among them even the serving-men of Chabrias [31].

Pedieus Painter, Musician supporting a drunken banqueter, Tondo from an Attic red-figure kylix, c. 510 BC, Louvre Museum, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

[34] To prove that these statements of mine are true, I will bring before you as witnesses those who were present and saw for themselves. Please call Chionides of Xypetê and Euthetion of Cydathenaeum.

Depositions: “Chionides of Xypetê and Euthetion of Cydathenaeum depose that they were invited to dinner by Chabrias, when he celebrated with a banquet his victory in the chariot race, and that the banquet was held at Colias; and that they know that Phrynion was present at the banquet, having with him Neaira, the present defendant; that they themselves lay down to sleep, as did Phrynion and Neaira, and that they observed that men got up in the night to go in to Neaira, among them some of the serving-men who were household slaves of Chabrias.”

[35] Since, then, she was treated with wanton outrage by Phrynion, and was not loved as she expected to be, and since her wishes were not granted by him, she packed up his household goods and all the clothing and jewelry with which he had adorned her person, and, taking with her two maid-servants, Thratta and Coccalinêe, ran off to Megara. This was the period when Asteius was archon at Athens (372 BCE), at the time you were waging your second war against the Lacedaemonians [Spartans].

[36] She remained at Megara [32] two years, that of the archonship of Asteius and that of Alcisthenes; but the trade of prostitution did not bring in enough money to maintain her establishment—she was lavish in her tastes, and the Megarians were stingy and ungenerous, and there were but few foreigners there on account of the war and because the Megarians favored the Lacedaemonian side, while you were in control of the sea; it was, however, not open to her to return to Corinth, because she had got her freedom from Eucrates and Timanoridas on the condition that she would not ply her trade in Corinth;—

[37] so, when peace was made in the archonship of Phrasicleides, and the battle was fought at Leuctra (371 BCE) between the Thebans [33] and the Lacedaemonians [Spartans], this man Stephanus, having at the time come to Megara and having put up at Neaira’s house, as at the house of a courtesan, and having had intercourse with her, she told him all that had taken place and her brutal treatment by Phrynion. She gave him besides all that she had brought away from Phrynion's house, and as she was eager to live at Athens, but was afraid of Phrynion because she had wronged him and he was bitter against her, and she knew he was a man of violent and reckless temper, she took Stephanus here for her patron [34].

[38] He on his part encouraged her there in Megara with confident words, boastfully asserting that if Phrynion should lay hands on her he would have cause to rue it, whereas he himself would keep her as his wife and would introduce the sons whom she then had to his clansmen as being his own, and would make them citizens; and he promised that no one in the world should harm her. So he brought her with him from Megara to Athens, and with her three children, Proxenus and Ariston and a daughter whom they now call Phano.

[39] He established her and her children in the cottage which he had near the Whispering Hermes [35] between the house of Dorotheus the Eleusinian [36] and that of Cleinomachus—the cottage which Spintharus has now bought from him for seven minae; so the property which Stephanus owned was just this and nothing besides. There were two reasons why he brought her here: first, because he would have a beautiful mistress without cost, and secondly, because her earnings would procure supplies and maintain the house; for he had no other income save what he might get by unethical matters.

[40] Phrynion, however, learned that the woman was in Athens, and was living with Stephanus, and taking some young men with him he came to the house of Stephanus and attempted to carry her off. When Stephanus took her away from him, as the law allowed, declaring her to be a free woman, Phrynion required her to post bonds with the polemarch [until her status was proven] [37]. To prove that this statement is true, I will bring before you as a witness to these facts the man himself who was polemarch at the time. Please call Aeetes of Ceiriadae.

[Deposition]: “Aeetes of Ceiriadae deposes that while he was polemarch, Neaira, the present defendant, was required by Phrynion, the brother of Demochares, to post bonds, and that the sureties of Neaira were Stephanus of Eroeadae, Glaucetes of Cephisia, and Aristocrates of Phalerum.”

[41] Now that Stephanus had become surety for her, and seeing that she was living at his house, she continued to carry on the same trade no less than before, but she charged higher fees from those who sought her favors as being now a respectable woman living with her husband. Stephanus, on his part, joined with her in extorting blackmail. If he found as a lover of Neaira any young alien rich and without experience, he would lock him up as caught in adultery with her, and would extort a large sum of money from him.

[42] And this course was natural enough; for neither Stephanus nor Neaira had any property to supply funds for their daily expenditures, and the expenses of their establishment were large; for they had to support both him and her and three children whom she had brought with her, and two female servants and a male house-servant; and besides Neaira had become accustomed to live comfortably, since heretofore others had provided the cost of her maintenance.

[43] This fellow Stephanus was getting nothing worth mentioning from public business, for he was not yet a public speaker, but thus far merely a disreputable person, one of those [sycophants] who stand beside the platform and shout, who prefer indictments and informations for hire, and who let their names be inscribed on motions made by others, up to the day when he became an underling of Callistratus of Aphidna [38]. How this came about and for what cause I will tell you in detail regarding this matter also, when I shall have proved regarding this woman Neaira that she is an alien (metic) and is guilty of grievous wrongs against you and of impiety towards the gods;

[44] for I would have you know that Stephanus himself deserves to pay no less heavy a penalty than Neaira here, but even one far heavier, and that he is far more guilty, seeing that, while professing to be an Athenian, he treats you and your laws and the gods with such utter contempt that he cannot bring himself to keep quiet even for shame at the wrongs he has himself committed, but by bringing baseless charges against me and against others he has caused my colleague to bring against him and against this woman a charge so grievous that it necessitates inquiry being made into her origin, and his own wasteful extravagance being brought to light.

[45] So, then, Phrynion brought suit against Stephanus for having taken this woman Neaira from him and asserted her freedom, and for having received the goods which Neaira had brought with her from Phrynion's house. Their friends, however, brought them together and induced them to submit their quarrel to arbitration. On behalf of Phrynion, Satyrus of Alopecê, the brother of Lacedaemonius, sat as arbitrator, and on behalf of Stephanus here, Saurias of Lamptrae; and they added to their number by common consent Diogeiton of Acharnae.

[46] These men came together in the temple, and after hearing the facts from both parties and from the woman herself gave their decision, and these men acceded to it. The terms were: that the woman should be free and her own mistress, but that she should give back to Phrynion all that she had taken with her from his house except the clothing and the jewels and the maid-servants; for these had been bought for the use of the woman herself; and that she should live with each of the men on alternate days, and if they should mutually agree upon any other arrangement, that arrangement should be binding; that she should be maintained by the one who for the time had her in his keeping; and that for the future the men should be friends with one another and bear no malice.

Examples of Greek gold jewelry, including earrings and dress pins, from the Ashmolean Museum (Oxford). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

[47] Such were the terms of the reconciliation effected by the arbitrators between Phrynion and Stephanus in regard to this woman Neaira. To prove that these statements of mine are true, the clerk shall read you the deposition regarding these matters. Please call Satyrus of Alopecê, Saurias of Lamptrae, and Aristogeiton of Acharnae.

[Deposition]: “Satyrus of Alopecê, Saurias of Lamptrae, and Diogeiton of Acharnae depose that, having been appointed arbitrators in the matter of Neaira, the present defendant, they brought about a reconciliation between Stephanus and Phrynion, and that the terms on which the reconciliation was brought about were such as Apollodorus produces.”

[Terms of reconciliation]: “They have reconciled Phrynion and Stephanus on the following terms: that each of them shall keep Neaira at his house and have her at his disposal for an equal number of days in the month, unless they shall themselves agree upon some other arrangement.”

[48] When the reconciliation had been brought about, those who had assisted either party in the arbitration and the whole affair did just what I fancy is always done, especially when the quarrel is about a courtesan. They went to dine at the house of whichever of the two had Neaira in his keeping, and the woman dined and drank with them, as being a courtesan.

To prove that these statements of mine are true, call, please as witnesses those who were present with them, Eubulus of Probalinthus, Diopeithes of Melitê, and Cteson of Cerameis.

[Deposition]: “Eubulus of Probalinthus, Diopeithes of Melitê, and Cteson of Cerameis, depose that after the reconciliation in the matter of Neaira was brought about between Phrynion and Stephanus they frequently dined with them and drank in the company of Neaera, the present defendant, both when Neaira was at the house of Stephanus and when she was at the house of Phrynion.”

[49] I have, then, shown you in my argument, and the testimony of witnesses has proved: that Neaira was originally a slave, that she was twice sold, that she made her living by prostitution as a courtesan; that she ran away from Phrynion to Megara, and that on her return she was forced to give bonds as an alien before the polemarch. I wish now to show you that Stephanus here has himself given evidence against her, proving her to be an alien.

"Wedding preparation", Sicilian, the Adrano Group, 330-320 BCE. Clay, glaze, added white, blue, yellow. Pushkin museum, Moscow. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

[50] The daughter of this woman Neaira, whom she brought with her as a small child to the house of Stephanus, and whom they then called Strybele, but now call Phano, was given in marriage by this fellow Stephanus as being his own daughter to an Athenian, Phrastor, of Aegilia; and a marriage portion [39] of thirty minae was given with her. When she came to the house of Phrastor, who was a laboring man and one who had acquired his means by frugal living, she did not know how to adjust herself to his ways, but sought to emulate her mother's habits and the dissolute manner of living in her house, having, I suppose, been brought up in such licentiousness.

[51] Phrastor, seeing that she was not a decent woman and that she was not minded to listen to his advice, and, further, having learned now beyond all question that she was the daughter, not of Stephanus, but of Neaira, and that he had been deceived in the first place at the time of the betrothal, when he had received her as the daughter, not of Neaira, but of Stephanus by an Athenian woman, whom he had married before he lived with Neaira—angered at all this and considering that he had been treated with outrage and hoodwinked, he put away the woman after living with her for about a year, she being pregnant at the time, and refused to pay back the marriage portion.

[52] Stephanus brought suit for alimony against him in the Odeum in accordance with the law which enacts that, if a man puts away his wife, he must pay back the marriage portion or else pay interest on it at the rate of nine obols [40] a month for each mina [41]; and that on the woman's behalf her guardian may sue him for alimony in the Odeum. Phrastor, on his part, preferred an indictment against Stephanus before the Thesmothetae, charging that he had betrothed to him, being an Athenian, the daughter of an alien woman as though she were his own. This was in accordance with the following law. Read it, please.

[Law]: “If anyone shall give an alien woman in marriage to an Athenian man, representing her as being related to himself, he shall lose his civic rights and his property shall be confiscated, and a third part of it shall belong to the one who secures his conviction. And anyone entitled to do so may indict such a person before the Thesmothetae, just as in the case of usurpation of citizenship.”

[53] The clerk has read you the law in accordance with which this fellow Stephanus was indicted by Phrastor before the Thesmothetae. Stephanus, then, knowing that, if he were convicted of having given in marriage the daughter of an alien woman, he would be liable to the heaviest penalties, came to terms with Phrastor and relinquished his claim to marriage portion, and withdrew his action for alimony; and Phrastor on his part withdrew indictment from the Thesmothetae. To prove that my statements are true, I will call before you as witness to these facts Phrastor himself, and will compel him to give testimony as the law commands.

[54] Please call Phrastor of Aegilia. [Deposition]: “Phrastor of Aegilia deposes that, when he learned that Stephanus had given him in marriage a daughter of Neaera, representing that she was his own daughter, he lodged an indictment against him before the Thesmothetae, as the law provides, and drove the woman from his house, and ceased to live with her any longer; and that after Stephanus had brought suit against him in the Odeum for alimony, he made an arrangement with him on the terms that the indictment before the Thesmothetae should be withdrawn, and also the suit for alimony which Stephanus had brought against me.”

[55] Now let me bring before you another deposition of Phrastor and his clansmen and the members of his gens, which proves that the defendant Neaira is an alien. Not long after Phrastor had sent away the daughter of Neaira, he fell sick. He got into a dreadful condition and became utterly helpless. There was an old quarrel between him and his own relatives, toward whom he cherished anger and hatred; and besides he was childless. Being cajoled, therefore, in his illness by the attentions of Neaira and her daughter—

[56] they came while he lay sick and had no one to care for him, bringing him the medicines suited to his case and looking after his needs; and you know of yourselves what value a woman has in the sick-room, when she waits upon a man who is ill—well, he was induced to take back and adopt as his son the child whom the daughter [Phano] of this woman Neaira had borne after she was sent away from his house in a state of pregnancy, after he had learned that she was the daughter, not of Stephanus, but of Neaira, and was angered at their deceit.

[57] His reasoning in the matter was both natural and to be expected. He was in a precarious condition and there was not much hope that he would recover. He did not wish his relatives to get his property nor himself to die childless, so he adopted this boy and received him back into his house. That he would never have done this, if he had been in good health, I will show you by a strong and convincing proof.

Marlay Painter, Marriage procession: the bride is driven in a chariot from her parent's home to that of her husband, Attic red-figure pyxis, 440-430 BCE, © Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia Commons.

[58] For no sooner had Phrastor got up from that sickness and recovered his health and was fairly well, than he took to wife, according to the laws, an Athenian woman, the legitimate daughter of Satyrus, of Melitê, and the sister of Diphilus. Let this, therefore, be a proof to you that he took back the child, not willingly, but forced by his sickness, by his childless condition, by the care shown by these women in nursing him, and by the enmity which he felt toward his own relatives, and his wish that they should not inherit his property, if anything should happen to him. This will be proved to you even more clearly by what followed.

[59] For when Phrastor at the time of his illness sought to introduce the boy born of the daughter of Neaira [Phano] to his clansmen and to the Brytidae, to which gens [42] Phrastor himself belongs, the members of the gens, knowing, I fancy, who the woman was whom Phrastor first took to wife, that, namely, she was the daughter of Neaira, and knowing, too, of his sending the woman [Phano] away, and that it was because of his illness that Phrastor had been induced to take back the child, refused to recognize the child and would not enter him on their register.

[60] Phrastor brought suit against them for refusing to register his son, but the members of the gens challenged him before the arbitrator to swear by full-grown victims that he verily believed the boy to be his own son, born of an Athenian woman and one betrothed to him in accordance with the law. When the members of the gens tendered this challenge to Phrastor before the arbitrator, he refused to take the oath, and did not swear.

[61] To prove that these statements of mine are true, I will bring before you as witnesses the members of the Brytid gens who were present.

Witnesses: “Timostratus of Hecalê, Xanthippus of Eroeadae, Evalces of Phalerum, Anytus of Laciadae, Euphranor of Aegilia and Nicippus of Cephalê, depose [testify] that both they and Phrastor of Aegilia are members of the gens called Brytidae, and that, when Phrastor claimed the right to introduce a son of his into the gens, they, on their part, knowing that Phrastor's son was born of the daughter of Neaira, would not suffer Phrastor to introduce his son.”

[62] I prove to you, therefore, in a manner that leaves no room for doubt that even those most nearly connected with this woman Neaira have given testimony against her, proving that she is an alien—Stephanus here, who now keeps the woman and lives with her, and Phrastor, who took her daughter [Phano] to wife—Stephanus, since he refused to go on trial on behalf of this daughter when he was indicted by Phrastor before the Thesmothetae on the charge that he had betrothed the daughter of an alien to him who was an Athenian, but had rather relinquished the claim to the marriage portion, and had not recovered it;

[63] and Phrastor, since he had put away the daughter of this Neaira [Phano] after marrying her, when he learned that she was not the daughter of Stephanus, and had refused to return her marriage portion; and when later on he was induced by his illness and his childless condition and his enmity toward his relatives to adopt the child, and when he sought to introduce him to the members of the gens, and they voted to reject the child and challenged him to take an oath, he refused to swear, but chose rather to avoid committing perjury, and subsequently married in accordance with the law another woman who was an Athenian. These facts, about which there is no room for doubt, have afforded you convincing testimony against our opponents, proving that this Neaira is an alien.

[64] Now observe the base love of gain and the villainous character of this fellow Stephanus, in order that from this again you may be convinced that this Neaera is not an Athenian woman. Epaenetus, of Andros, an old lover of Neaira, who had spent large sums of money upon her, used to lodge with these people whenever he came to Athens on account of his affection for Neaira. Against him this man Stephanus laid a plot.

[65] He sent for him to come to the country under pretense of a sacrifice and then, having surprised him in adultery with the daughter of this Neaera, intimidated him and extorted from him thirty minae. As sureties for this sum he accepted Aristomachus, who had served as Thesmothete, and Nausiphilus, the son of Nausinicus, who had served as archon [43], and then released him under pledge that he would pay the money.

[66] Epaenetus, however, when he got out and was again his own master preferred before the Thesmothetae an indictment for unlawful imprisonment against this Stephanus in accordance with the law which enacts that, if a man unlawfully imprisons another on a charge of adultery, the person in question may indict him before the Thesmothetae on a charge of illegal imprisonment; and if he shall convict the one who imprisoned him and prove that he was the victim of an unlawful plot, he shall be let off scot-free, and his sureties shall be released from their engagement; but if it shall appear that he was an adulterer, the law bids his sureties give him over to the one who caught him in the act, and he in the court-room may inflict upon him, as upon one guilty of adultery, whatever treatment he pleases, provided he use no knife.

[67] It was in accordance with this law that Epaenetus indicted Stephanus. He admitted having intercourse with the woman, but denied that he was an adulterer; for, he said, she was not the daughter of Stephanus, but of Neaira, and the mother knew that the girl was having intercourse with him, and he had spent large sums of money upon them, and whenever he came to Athens he supported the entire household. In addition to this he brought forward the law which does not permit one to be taken as an adulterer who has to do with women who sit professionally in a brothel or who openly offer themselves for hire; for this, he said, is what the house of Stephanus is, a house of prostitution; this is their trade, and they get their living chiefly by this means.

[68] When Epaenetus had made these statements and had preferred the indictment, this Stephanus, knowing that he would be convicted of keeping a brothel and extorting blackmail, submitted his dispute with Epaenetus for arbitration to the very men who were the latter's sureties on the terms that they should be released from their engagement and that Epaenetus should withdraw the indictment.

[69] Epaenetus acceded to these terms and withdrew the indictment which he had preferred against Stephanus, and a meeting took place between them at which the sureties sat as arbitrators. Stephanus could say nothing in defense of his action, but he requested Epaenetus to make a contribution toward a dowry for Neaira’s daughter, making mention of his own poverty and the misfortune which the girl had formerly met with in her relations with Phrastor, and asserting that he had lost her marriage portion and could not provide another for her.

[70] “You,” he said, “have enjoyed the woman’s favors, and it is but right that you should do something for her.” He added other words calculated to arouse compassion, such as anyone might use in entreaty to get out of a nasty mess. The arbitrators, after hearing both parties, brought about a reconciliation between them, and induced Epaenetus to contribute one thousand drachmae toward the marriage portion of Neaira's daughter. To prove the truth of these statements of mine, I will call as witnesses to these facts the very men who were sureties and arbitrators:

[71] [Witnesses] “Nausiphilus of Cephalê and Aristomachus of Cephalê depose that they became sureties for Epaenetus of Andros, when Stephanus asserted that he had caught Epaenetus in adultery; and that when Epaenetus had got away from the house of Stephanus and had become his own master, he preferred before the Thesmothetae an indictment against Stephanus for illegal imprisonment; that they were themselves appointed as arbitrators, and brought about a reconciliation between Epaenetus and Stephanus, and that the terms of the reconciliation were those which Apollodorus produces.”

[Terms of Reconciliation]: “The arbitrators brought about a reconciliation between Stephanus and Epaenetus on the following terms: they shall bear no malice for what took place regarding the imprisonment; Epaenetus shall give to Phano one thousand drachmae toward her marriage portion, inasmuch as he has frequently enjoyed her favors; and Stephanus shall put Phano at the disposal of Epaenetus whenever he comes to Athens and wishes to enjoy her.”

[72] Although this woman [Phano], then, was acknowledged beyond all question to be an alien, and although Stephanus had had the audacity to charge with adultery a man taken with her, these two, Stephanus and Neaira, came to such a pitch of insolence and shamelessness that they were not content with asserting her to be of Athenian birth; but observing that Theogenes, of Cothocidae [44], had been selected by lot as king, a man of good birth, but poor and without experience in affairs, this Stephanus, who had assisted him at his scrutiny and had helped him meet his expenses when he entered upon his office, wormed his way into his favor, and by buying the position from him got himself appointed his assessor. He then gave him in marriage this woman [Phano], the daughter of Neaira, and betrothed her to him as being his own daughter; so utterly did he scorn you and your laws.

[73] And this woman [Phano] offered on the city's behalf the sacrifices which none may name, and saw what it was not fitting for her to see, being an alien; and despite her character she entered where no other of the whole host of the Athenians enters save the wife of the king only; and she administered the oath to the venerable priestesses who preside over the sacrifices, and was given as bride to Dionysus [45]; and she conducted on the city's behalf the rites which our fathers handed down for the service of the gods, rites many and solemn and not to be named. If it be not permitted that anyone even hear of them, how can it be consonant with piety for a chance-comer to perform them, especially a woman of her character and one who has done what she has done?

[74] I wish, however, to go back farther and explain these matters to you in greater detail, that you may be more careful in regard to the punishment, and may be assured that you are to cast your votes, not only in the interest of yourselves and the laws, but also in the interest of reverence towards the gods, by exacting the penalty for acts of impiety, and by punishing those who have done the wrong. In ancient times, men of Athens, there was sovereignty in our state, and the kingship belonged to those who were from time to time preeminent by reason of their being children of the soil, and the king offered all the sacrifices, and those which were holiest and which none might name his wife performed, as was natural, she being queen.

[75] But when Theseus settled the people in one city and established the democracy, and the city became populous, the people nonetheless continued to elect the king as before, choosing him from among those most distinguished by valor; and they established a law that his wife should be of Athenian birth, and that he should marry a virgin who had never known another man, to the end that after the custom of our fathers the sacred rites that none may name may be celebrated on the city's behalf, and that the approved sacrifices may be made to the gods as piety demands, without omission or innovation.

[76] This law they wrote on a pillar of stone, and set it up in the sanctuary of Dionysus by the altar in Limnae (and this pillar even now stands, showing the inscription in Attic characters, nearly effaced). Thus the people testified to their own piety toward the god, and left it as a deposit for future generations, showing what type of woman we demand that she shall be who is to be given in marriage to the god, and is to perform the sacrifices. For this reason they set it up in the most ancient and most sacred sanctuary of Dionysus in Limnae [46], in order that few only might have knowledge of the inscription; for once only in each year is the sanctuary opened, on the twelfth day of the month Anthesterion [47].

[77] These sacred and holy rites for the celebration of which your ancestors provided so well and so magnificently, it is your duty, men of Athens, to maintain with devotion, and likewise to punish those who insolently defy your laws and have been guilty of shameless impiety toward the gods; and this for two reasons: first, that they may pay the penalty for their crimes; and, secondly, that others may take warning, and may fear to commit any sin against the gods and against the state.

[78] I wish now to call before you the sacred herald who waits upon the wife of the king, when she administers the oath to the venerable priestesses as they carry their baskets in front of the altar before they touch the victims [48], in order that you may hear the oath and the words that are pronounced, at least as far as it is permitted you to hear them; and that you may understand how august and holy and ancient the rites are.

The Oath of the Venerable Priestesses: “I live a holy life and am pure and unstained by all else that pollutes and by commerce with man, and I will celebrate the feast of the wine god and the Iobacchic feast in honor of Dionysus in accordance with custom and at the appointed times.”

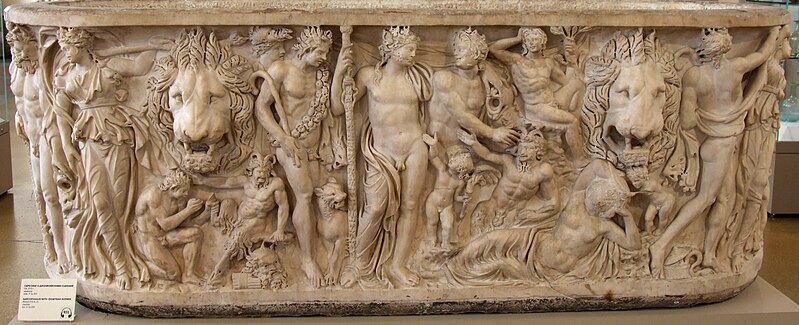

Sarcophagus with Dionysian scenes, 210s CE, Pushkin museum, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

[79] You have heard the oath and the accepted rites handed down by our fathers, as far as it is permitted to speak of them, and how this woman, whom Stephanus betrothed to Theogenes when the latter was king, as his own daughter, performed these rites, and administered the oath to the venerable priestesses; and you know that even the women who behold these rites are not permitted to speak of them to anyone else. Let me now bring before you a piece of evidence which was, to be sure, given in secret, but which I shall show by the facts themselves to be clear and true.

[80] When these rites had been solemnized and the nine archons had gone up on the Areopagus [49] on the appointed days, the council of the Areopagus, which in other matters also is of high worth to the city in what pertains to piety, forthwith undertook an inquiry as to who this wife of Theogenes was and established the truth; and being deeply concerned for the sanctity of the rites, the council was for imposing upon Theogenes the highest fine in its power, but in secret and with due regard for appearances; for they have not the power to punish any of the Athenians as they see fit.

[81] Conferences were held, and, seeing that the council of the Areopagus was deeply incensed and was disposed to fine Theogenes for having married a wife of such character and having permitted her to administer on the city's behalf the rites that none may name, Theogenes besought them with prayers and entreaties, declaring that he did not know that she was the daughter of Neaira, but that he had been deceived by Stephanus, and had married her according to the law as being the latter's legitimate daughter; and that it was because of his own inexperience in affairs and the guilelessness of his character that he had made Stephanus his assessor to attend to the business of his office; for he considered him a friend, and on that account had become his son-in-law.

[82] “And,” he said, “I will show you by a convincing and manifest proof that I am telling the truth. I will send the woman away from my house, since she is the daughter, not of Stephanus, but of Neaira. If I do this, then let my statement that I was deceived be accepted as true; but, if I fail to do it, then punish me as a vile fellow who is guilty of impiety toward the gods.”

[83] When Theogenes had made this promise and this plea, the council of the Areopagus, through compassion also for the guilelessness of his character and in the belief that he had really been deceived by Stephanus, refrained from action. And Theogenes immediately on coming down from the Areopagus cast out of his house the woman, the daughter of this Neaira, and expelled this man Stephanus, who had deceived him, from the board of magistrates [50]. Thus it was that the members of the Areopagus desisted from their action against Theogenes and from their anger against him; for they forgave him, because he had been deceived.

[84] To prove the truth of these statements of mine, I will call before you as a witness to these facts Theogenes himself, and will compel him to testify. Call, please, Theogenes of Erchia.

Witness deposition: “Theogenes of Erchia deposes that when he was king he married Phano, believing her to be the daughter of Stephanus, and that, when he found he had been deceived, he cast the woman away and ceased to live with her, and that he expelled Stephanus from his post of assessor, and no longer allowed him to serve in that capacity.”

[85] Now take, please, the law bearing upon these matters, and read it; for I would have you know that a woman of her character, who has done what she has done, ought not only to have kept aloof from these sacred rites, to have abstained from beholding them, from offering sacrifices, and from performing on the city's behalf any of the ancestral rites which usage demands, but that she should have been excluded also from all other religious ceremonials in Athens. For a woman who has been taken in adultery is not permitted to attend any of the public sacrifices, although the laws have given both to the alien woman and the slave the right to attend these, whether to view the spectacle or to offer prayer.

Woman pouring a libation [drink offering]. Detail from an Attic white-ground lekythos, ca. 460 BC, British Museum, © Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia Commons

[86] No; it is to these women alone that the law denies entrance to our public sacrifices, to these, I mean, who have been taken in adultery; and if they do attend them and defy the law, any person whatsoever may at will inflict upon them any sort of punishment, save only death, and that with impunity; and the law has given the right of punishing these women to any person who happens to meet with them. It is for this reason that the law has declared that such a woman may suffer any outrage short of death without the right of seeking redress before any tribunal [51] whatsoever, that our sanctuaries may be kept free from all pollution and desecration, and that our women may be inspired with a fear sufficient to make them live soberly, and avoid all vice, and, as their duty is, to keep to their household tasks. For it teaches them that, if a woman is guilty of any such sin, she will be an outcast from her husband's home and from the sanctuaries of the city.

[87] That this is so, you will see clearly, when you have heard the law read. Take it please.

[Law]: “When he has caught the adulterer, it shall not be lawful for the one who has caught him to continue living with his wife, and if he does so, he shall lose his civic rights and it shall not be lawful for the woman who is taken in adultery to attend public sacrifices; and if she does attend them, she may be made to suffer any punishment whatsoever, short of death, and that with impunity.”

[88] I wish now, men of Athens, to bring before you the testimony also of the Athenian civic body, to show you how great care they take in regard to these religious rites. For the civic body of Athens, although it has supreme authority over all things in the state, and it is in its power to do whatsoever it pleases, yet regarded the gift of Athenian citizenship as so honorable and so sacred a thing that it enacted in its own restraint laws to which it must conform, when it wishes to create a citizen—laws which now have been dragged through the mire [52] by Stephanus and those who contract marriages of this sort.

[89] However, you will be the better for hearing them, and you will know that these people have debased the most honorable and the most sacred gifts, which are granted to the benefactors of the state. In the first place, there is a law imposed upon the people forbidding them to bestow Athenian citizenship upon any man who does not deserve it because of distinguished services to the Athenian people. In the next place, when the civic body has been thus convinced and bestows the gift, it does not permit the adoption to become valid, unless in the next ensuing assembly more than six thousand Athenians confirm it by a secret ballot.

[90] And the law requires the presidents to set out the ballot boxes and to give the ballots to the people as they come up before the non-citizens have come in and the barriers have been removed, in order that every one of the citizens, being absolutely free from interference, may form his own judgment regarding the one whom he is about to make a citizen, whether the one about to be so adopted is worthy of the gift. Furthermore, after this the law permits to any Athenian who wishes to prefer it an indictment for illegality against the candidate, and he may come into court and prove that the person in question is not worthy of the gift, but has been made a citizen contrary to the laws.

[91] And there have been cases before now when, after the people had bestowed the gift, deceived by the arguments of those who requested it, and an indictment for illegality had been preferred and brought into court, the result was that the person who had received the gift was proved to be unworthy of it, and the court took it back. To review the many cases in ancient times would be a long task; I will mention only those which you all remember: Peitholas the Thessalian, and Apollonides the Olynthian, after having been made citizens by the people, were deprived of the gift by the court.

[92] These are not events of long ago of which you might be ignorant. However, although the laws regarding citizenship and the steps that must be taken before one may become an Athenian are so admirably and so securely established, there is yet another law which has been enacted in addition to all these, and this law is of paramount validity; such great precautions have the people taken in the interest of themselves and of the gods, to the end that the sacrifices on the state's behalf may be offered in conformity with religious usage. For in the case of all those whom the Athenian people may make citizens, the law expressly forbids that they should be eligible to the office of the nine archons or to hold any priesthood; but their descendants are allowed by the people to share in all civic rights, though the proviso [53] is added: if they are born from an Athenian woman who was betrothed according to the law.

[93] That these statements of mine are true, I will prove to you by the clearest and most convincing testimony; but I wish first to go back to the origins of the law and to show how it came to be enacted and who those were whom its provisions covered as being men of worth who had shown themselves staunch friends to the people of Athens. For from all this you will know that the people's gift which is reserved for benefactors is being dragged through the mire, and how great the privileges are which are being taken from your control by this fellow Stephanus and those who have married and begotten children in the manner followed by him.

[94] The Plataeans, men of Athens, alone among the Greeks came to your aid at Marathon [54] (490 BCE) when Datis, the general of King Darius [of Persia], on his return from Eretria [55] after subjugating Euboea [56], landed on our coast with a large force and proceeded to ravage the country. And even to this day the picture in the Painted Stoa exhibits the memorial of their valor; for each man is portrayed hastening to your aid with all speed—they are the band wearing Boeotian [57] caps.

[96] And they fought together with you and the others who were seeking to save the freedom of Greece in the final battle at Plataea [58] against Mardonius, the King's general, and deposited the liberty thus secured as a common prize for all the Greeks. And when Pausanias, the king of the Lacedaemonians, sought to put an insult upon you, and was not content that the Lacedaemonians had been honored by the Greeks with the supreme command, and when your city, which in reality had been the leader in securing liberty for the Greeks, forbore to strive with the Lacedaemonians as rivals for the honor through fear of arousing jealousy among the allies;