1.1: Fundamentals of Music

- Page ID

- 174750

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)This fundamental material established core vocabulary and concepts that will be used through the course. These six groups below will help students be able to understand how music works, breaking the music down in the sonic elements. Each group—Timbre, Dynamics, Pitch, Melody & Harmony, Time & Form, and Texture.

-

TIMBRE

the way a sound sounds to distinguish one sound from another.

The word timbre (pronounced: tam-ber) can be highly subjective. Timbre is the way something sounds, e.g., the singer sounds nasal. Synonyms for timbre often include “tone color,” “sound quality,” or “character of sound.” This concept is not meant to be a judgment statement, but a description that helps to identify similarities and differences between sounds and music.

Imagine trying to describe two instruments of the same type, a guitar, and a ‘ukulele, for example. Describing the way these two instruments sound similar and different helps to distinguish them sonically, see Examples 1.1 (guitar) and 1.2 (‘ukulele) below.

Example 1.1 (Guitar) O'Carolan: Si Bheag, Si Mhor, artist: Jack IsidoreWatch on YouTube [www.youtube.com] Creative Commons |

Example 1.2 (Ukulele) "Hawaiian Waltz" artists: Kamiki UkuleleWatch on YouTube [www.youtube.com]Creative Commons |

|---|

Describing two or more unrelated instruments/sounds can be easier. However, if the instruments are playing at the same time, it can still be difficult to distinguish them. Listen to the example below played on traditional Chinese instruments. Use the listening guide to help you distinguish between the different timbres.

Example 1.3 “Etenraku” artists: Tokyo Gagaku

Watch on YouTube [www.youtube.com]

| Description: | Each instrument is playing the same melody so distinguishing each instrument’s sound is important to understand how the music is working. The differences between the instruments, the way they sound, is the timbre. |

|---|---|

| 0:06-0:18 | Solo flute (ryuteki) part establishing the melody |

| 0:19 | Mouth organs (sho) play note cluster of melodic line |

| 0:21 | Ensemble joins flute and organs in playing melody, each line has their own established embellishments but each is playing the same melody. |

The examples thus far demonstrate different types of timbral descriptions, but there are numerous descriptors to use. Listen to each example and describe what you hear.

Other ways to describe timbre are to point out features used by the voices/instruments. Listen to the singer in Example 1.4, below. They are using a strong vibrato but the melody in Example 1.3 above uses a straight tone.

Example 1.4 "La Charreada" artist: Sandra Gonzalez y el Mariachi Alas de Mexico de Guadalajara Jalisco

Watch on YouTube [www.youtube.com]

| Description: | Example 1.4 "La Charreada" artist: Sandra Gonzalez y el Mariachi Alas de Mexico de Guadalajara Jalisco |

|---|---|

| 0:00-0:23 | Instrumental and vocal intro |

| 0:24-0:28 | Vocal vibrato on sustained opening note |

Example 1.5 Beijing Opera DADENGDIAN Artist: Shengsu Li

Watch on YouTube [www.youtube.com]

This Chinese jingju is known for its nasal qualities (Example 1.5) while the singer in Example 1.4 has a full round sound. There are numerous descriptor words that will be addressed in this class, some may include: rough/smooth, falsetto/chest voice, airy/full, etc.

-

a pitch fluctuation added to a sustained note for a richer sound

lack of pitch fluctuation on a sustained note

closed off timbre that sounds like it is produced from the nasal cavity

open timbre with full resonance

-

DYNAMICS

relative loudness/softness of sound; volume

While this element seems easier than others, the real key is to pinpoint which sounds are louder, and softer, than others in music. This will help describe that sound more clearly. Many students with previous music experience will know standard musical terms, often from Italian, French, and German (e.g., crescendo, pianissimo, forte, etc.). While these words are useful, for the purposes of this class, it is easier to avoid such terms. Describing music as having an increase in volume from a quiet section to a louder section is just as effective.

Example 2.1 "Drive" Artist: Hilton College Marimba Ensemble

Watch on YouTube [youtu.be]

-

PITCH

frequency of a sound; highness or lowness of a sound

For this text, “pitch” is used as both a specific term, as defined above, and a grouping of concepts that encompass many ideas related to that specific term. Two common synonyms for “pitch” include tone and note, all may be used throughout the text.

Music is made of many sounds. Pitches are distinguished from other sounds as they have measurable frequencies. Each pitch has a specific wavelength, known as a frequency and measured in hertz. The frequency is an indication of how fast or slow the wavelength moves. This measurement is, of course, culturally derived and not universally recognized around the world or throughout history.

Many concepts are brought together in the grouped idea of “pitch.”

the “base note” that the melody is based (synonym: tonic)

- the distance between two pitches

the distance between the highest pitch and lowest pitch in a melody

a doubling of a frequency but the same pitch set. For example pitches may have the same name in western music, but a double or halved frequency. Low A vs High A

culturally prescribed arrangements of intervals and pitches

Example 3.1 "I'll Fly Away" Artist- David Durrence

Watch on YouTube [www.youtube.com]

| Description: | This example uses a fundamental tone that is continuously played on the lower string as the melody is played on a higher string as the performer moves his fingers on the board. The pitch range is somewhat narrow with the use of only 4-6 notes in a medium to low range of the instrument. |

|---|

-

MELODY & HARMONY

-

Melody: a sequence of pitches perceived as a unit (synonym: tune)

Melodies can be described with many characteristics from the way the melody line moves to the way other sounds harmonize with or support the melody.

stepwise (small intervals) melodic motion

Example 4.1 "Aloha Oe" Artist: Luanna Farden McKenney

Watch on YouTube [www.youtube.com]

| Description: | This is an example of stepwise motion. There are few jumps in the melody even though the range is large. |

|---|

Melodic motion by leaps (large intervals)

Example 4.2 Crossroad Blues by Robert Johnson; Artist: Edward Phillips

Watch on YouTube [youtu.be]

Description: This early 20th century blues song by Robert Johnson features a melody with large falling intervals.

Elaborations (decorations) on the set melody

Example 4.3 Ornamentation in Indian Music Artist: Anuja Kamat 2014

Watch on YouTube [www.youtube.com]

| Description: | This video goes through several types of ornamentation in Indian music. Each example includes a non-ornamented section followed by specific ornamentations. |

|---|

sections of the melody and music, often a “breath’s worth” of music

perception of the way musical layers sound together

Harmony is always culturally and time-based. Like timbre, harmony can be quite subjective. However, two descriptions of harmony are useful in understanding the music introduced in this class.

- Consonant harmony (consonance) – relaxed, open sounding harmony

- Dissonant harmony (dissonance) – tense, closed sounding harmony

Example 4.4 Jarabi Artist: Sona Jobarteh 2011

Watch on YouTube [www.youtube.com]

| Description: | This piece uses consonant harmony that in layman’s terms is often referred to as “happy” sounding due to the ease in which it is heard. Often, this music sounds “in tune,” but that is culturally dependent. |

|---|

Example 4.5 Song of the Spring Cicada Artist: Dong People 2009

Watch on YouTube [www.youtube.com]

| Description: | This highly layered music uses intentionally narrow intervals to create a dissonant sound. While it may seem “out of tune,” this is a culturally-based assumption. |

|---|

-

TIME & FORM

Time and Form are somewhat dependent on each other. Time is an understanding of the sequential framework of how the music is temporally organized. Form is an understanding of sections of music, which often can be noticed through changes in time.

“beat”: the background “heartbeat” of a piece of music

a pattern of sounds and silences that occur over time

The rate of speed of the music. The fastness or slowness.

the temporal description of the organization of pulse

- Accent – emphasis on a pulse

- Syncopation – destabilizing beat created with accents

Within the idea of meter, which is an understanding of the organization of the pulse, there are fixed and free meters. To determine the meter of music, first find the pulse.

Music with a free meter does not have a discernible and repeatable pattern in the pulse; the listener would not be able to find a regular beat, for instance, listen to Example 5.1.

Example 5.1 Honshirabe Artist Bronwyn Kirkpatrick 2012

Watch on YouTube [youtu.be]

| Description: | The music lacks a formal pulse. Not only is the tempo slow, but the rhythms are not easily understood as units together, but rather as independent thoughts. |

|---|

Music with a fixed meter has a clearly found and repeatable pattern in the pulse. Most music follows this form of meter.

Fixed meters have two basic categories: duple meter and triple meter. These meters have clearly defined pulsation and are organized in repeatable groupings of time. Duple meters are organized in divisions of 2 that alternate strong and weak beats. One of the most common duple meters in Western popular music and art music is a 4 beat meter where beats 1 and 3 are strong. Triple meters are organized in divisions of 3 with one strong beat (beat 1) followed by two weaker ones (beats 2 and 3). As you listen to Examples 5.2 and 5.3, you will be able to find the pulse easily. Tap your foot as you listen.

There are also complex meters that combine duple and triple organization, but the purposes of this class, these complex meters are rare and will not be discussed in detail.

|

Example 5.2: Duple meter Watch on YouTube [youtu.be] Description: Strong duple meter with accents on beats 2 and 4 emphasizing the repetitive nature of duple structure |

Example 5.3 Triple Meter El Son de la Negra Artist: Mariachi Vargas de Tacalitlan, 2018 Watch on YouTube [youtu.be] Description: As the music begins at around 0:18, the tempo increases locking into a strong triple meter. This meter is commonly heard in waltzes where beat 1 is weighted with beats 2 & 3 sounding a light "oom pas" |

|---|

-

TEXTURE

Most of the music you listen to has layers of different sounds, sometimes that is easier to hear than others. Think about a pop song and how the main voice stands out from the background sounds. In simple terms, you are hearing multiple layers of sound, this is texture in music.

Texture refers to the number of parts and the roles the parts play. There are four main types of texture: monophonic, homophonic, polyphonic, and heterophonic.

a single melody performed by one performer or a group of performers

MONOPHONIC TEXTURE includes just a single melody line (Figure 5.1) or a group of instruments/voices performing the same line in octaves (Figure 5/2). Example 5.1 below has a single layer of sound, first performed by a flute, then singing, then the flute again.

Figure 6.1: Single line of sound

Figure 6.2: Same line layered in octaves

Example 6.1: Monophonic texture

Ch'aska: Song for the Stars Artist: Don Pasqual Apaza Flores, 2015.

Watch on YouTube [www.youtube.com]

| Description: | |

|---|---|

| 0:00-0:38 | Single layer of flute playing |

| 0:38-1:13 | Single layer of singing |

| 1:13-1:37 |

Single layer of flute playing |

HOMOPHONIC TEXTURE includes two or more layers of sound, typically with one line sounding the melody. Again, think about pop music. The lead singer’s voice is the most important line, the backing vocals, instruments, and drum beats are secondary as they accompany the main melody coming from the singer. The second layer can be complex with textures of its own, but it remains a secondary layer to the main voice.

Figure 6.3: Melody in green with harmony, drums, and other sounds in red, blue, and black.

Example 6.2: Homophonic texture

Little Birdie Artist: The Kossoy Sisters 2013

Watch on YouTube [youtu.be]

| Description: | |

|---|---|

| 0:15-0:35 | Instrumental intro |

| 0:35-0:57 | Chorus: Singers sing in tight harmony with banjo and guitar becoming secondary to the vocal line (main melody) |

| 0:57-1:18 | Verse: Voice solo with banjo and guitar playing secondary line |

| 1:18-1:38 | Chorus: Singers sing in harmony with banjo and guitar in secondary line |

| 1:39-2:21 | Verse: Voice solo with banjo and guitar playing secondary line |

| 2:22-2:42 | Chorus: Singers sing in harmony with banjo and guitar in secondary line |

| 2:42-3:01 | Instrumental |

| 3:01-3:22 | Verse: Voice solo with banjo and guitar playing secondary line |

| 3:22-3:45 | Chorus: Singers sing in harmony with banjo and guitar in secondary line |

includes multiple lines that use contrary motion with interwoven layers of sound, resulting in two or more simultaneous independent melodies. This texture is commonly found in many choir and band compositions. There are multiple melody lines and when they are put together the multiple sounds complete a bigger picture.

Figure 6.4: No one melody throughout, each instrument group/voice build their individual part to create a more complex sound.

Example 6.3: Polyphonic texture

Shemokmedura Artist: Erisioni, 2013

Watch on YouTube [www.youtube.com]

| Description: | |

|---|---|

| 0:00-0:08 | 1st solo part |

| 0:08-0:17 | Harmonic layers added to solo part |

| 0:17-0:23 | 2nd solo part |

| 0:23-0:32 | Harmonic layers added to solo part with contrasting motion |

| 0:32 | 3rd solo part with harmonic layers |

| 0:42 | Yodel added in contrast to melody |

| 0:50-1: | Set of variations begin with more complex layering and more singers added |

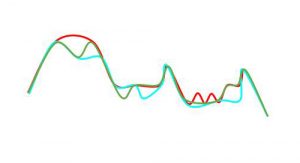

HETEROPHONIC TEXTURE includes at least two performers playing simultaneous variations of the same melody. Each performer/section embellished the melody on their own but play in unison for the majority of the music. The melodic line will move together in time and melodic shape without contrasting motion.

Figure 6.5: Single melody, duplicated by different instruments each with their own embellishment of the melody. Each line follows the basic shape of the melody but has slight variation from the other lines.

Example 6.4: Heterophonic texture

Etenraku Artist: Tokyo Gagaku, 2014

Watch on YouTube [www.youtube.com]

| Description: | |

|---|---|

| 0:06-0:18 | Solo flute (ryuteki) part establishing the melody |

| 0:19 | Mouth organs (sho) play note cluster of melodic line |

| 0:21 | Ensemble joins flute and organs in playing melody, each line has their own established embellishments but each is playing the same melody. |