21: The Protagonist

- Page ID

- 171034

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)21. The Protagonist

© 2021 Darren R. Reid and Brett Sanders, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0255.21

Documentaries are journeys: frequently for a person represented on the screen, always for the audience. As such, the emergence of your film during post-production should be informed by a sensitivity to change. Subjects should be given room to grow and develop, should they require it. And your audience, likewise, should have opportunities to deepen their knowledge about a subject in unexpected but intellectually satisfying ways. Representing and guiding that growth can be challenge, but there are clear precedents available to you that can inform how you approach this aspect of your work.

Joseph Campbell argued that narrative is a vital part of the human perceptual experience.1 It is in the details only that Star Wars (1977) is separated from The Lord of the Rings (2001–2003) and Breaking Bad (2008–2013). Walter White and Luke Skywalker might not appear to have much in common, but both Breaking Bad and Star Wars are about a character who a) craves change and b) through a shift of circumstances, is c) set on a path to realise some version of that change. Ultimately, both Skywalker and White are d) fundamentally altered by their quests to achieve some external goal, each becoming e) something the original character could not quite have envisaged at the start of their journey.2 This narrative structure, in one form or another, is evident in a vast array of Western narratives. Documentaries, though ostensibly very different from dramatic films, are just as likely to utilise this journey as their fictive counterparts.

It may be a false equivalence to talk about Walter White and Luke Skywalker in a discussion about documentary films, but consider Michael Moore’s first film, Roger and Me (1989), in which the filmmaker attempts to confront General Motors CEO Roger Smith about the impact his company’s downsizing policy has had upon Moore’s hometown of Flint, Michigan.3 In the film, Moore takes on the role of the film’s protagonist and, just like Luke Skywalker and Walter White, he a) craves change (through confrontation) and so b) changes his circumstances (becoming a documentarian) so that he can set off on a quest c) to initiate the confrontation. Moore ultimately fails to force the confrontation with Smith but is nonetheless d) altered by the experience, learning much (which he communicates to his audience) throughout his journey. As a result, Moore e) finds victory in his failure, discovering a deeper truth despite his inability to achieve his original goal. Considered from a structural perspective, there is little that meaningfully separates Moore from Skywalker or White.4 The substance of Roger and Me may be very different to that of a film like Star Wars, but the substructure of those films is remarkably similar. Even when no on-screen protagonist is identified in a documentary, one is always implied.

Consider Brian Cox’s BBC documentary series, Wonders of the Solar System (2011).5

Viewers might reasonably assume that the series’ charismatic presenter is its protagonist. This is not the case, however. Rather, it is the audience who unwittingly takes on that role and, in so doing, parallels the journeys taken by Moore, Skywalker, White, et al. It is, after all, the audience who a) craves a change in their initial state (to learn more) and, as a result, b) changes their intellectual circumstances by choosing to watch a documentary. From there they are able to c) confront their own ignorance, d) grow intellectually, face conceptual challenges, and e) emerge more enlightened.

Documentaries are, then, a form of participatory media. A distinction must therefore be drawn between those documentaries that feature an on-screen protagonist, like Moore in much of his work, and those that feature a guide whose principal responsibility is to facilitate the audience’s journey. Standardised narrative structures are common because they provide humans with a vector to understand the fundamentally disorganised and unstructured universe that surrounds them.6 As a result, narrative provides you with a powerful tool. It can help you to construct texts that recognise the participatory nature of the viewing experience, whilst simultaneously shaping a production around the audience’s role as active participants on an intellectual journey.

Harmon’s Story Embryo

Campbell proposes a seventeen-point journey for the ‘hero’ protagonist. Producer and writer Dan Harmon (Community (2009–2014), Rick and Morty (2013-present)) offers a more streamlined version of this model which aspires to even greater universality — and which we will revise and refine for the documentary format. According to Harmon, most, if not all, successful narratives can be distilled down to just eight core elements, which can be found in virtually every compelling example of the form. Whilst it is certainly possible that Harmon may have overstated the universality of his case, the structure he proposes does fit a remarkable number of filmic narratives, fiction and non-fiction alike.

At the root of Harmon’s argument is the idea that narrative, which he believes can be distilled down into a fundamental sub-structure he calls the story embryo, is hard-wired into the human imagination; that it serves as one of the key perceptual filters that allows the species to interpret and make sense of the world and their own lived experiences. As a result, fostering an accurate understanding of the universal mechanism of narrative, according to Harmon, has nothing to do with conforming to popular or transitory tropes or avoiding experimentation. Rather, it is an exercise in exploiting fundamental human psychology to create a method of information transmission which naturally resonates with an audience in an intuitive and impactful manner. It is, then, a tool that filmmakers can exploit to make their case in the most effective way possible.7

The story embryo argues that there are eight basic moments in any narrative which, together, make for an inherently satisfying structure. They are:

- The coming of a protagonist.

- That protagonist possesses a need for change (conversely, they may possess a particularly strong desire to maintain the status quo in the face of some external force).

- The protagonist must then move beyond their status quo. They must change their circumstances; in other words, leaving their comfort zone.

- The protagonist must then go on a quest in search of what they desire. If they wanted a change in their circumstances, they should attempt to realise that change. If they were taken out of their comfort zone by an external force, they might well be trying get back to their status quo.

- The protagonist should then find what they think they are looking for. If they wanted an exciting life, they should now be immersed within it and, at some point, embrace that change.

- The protagonist should then suffer as a result (undergo a setback of some kind).

- The protagonist must then recover from point six, overcoming a setback they encountered in order to complete their narrative arc. In Capitalism: A Love Story, this is the point when the mistreated factory workers stand up for themselves against the corporate mechanisms that had hitherto exploited them.8 In Star Wars, it is the point when Luke Skywalker resolves to join the rebel attack upon the Death Star, overcoming the death of his mentor, Obi Wan Kenobi.

- The protagonist can then emerge from their recovery a changed, usually improved, person. The arc is complete.9

In drama, the story embryo can be found in many films. The story of Luke Skywalker fits the model remarkably well, as does Michael Corleone in Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather (1972), Woody Allen’s Alvy Singer in Annie Hall (1979), Indiana Jones in Steven Spielberg’s Raiders of the Lost Arc (1981), Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s Amélie in Amélie (2001), and hundreds of others besides.10 For filmmaker-scholars, this model is even more important when the audience’s participatory role is recalled and utilised fully.

Casting the Audience as the Protagonist

When the audience is projected onto Harmon’s model, no less than half of the protagonist’s journey occurs before a single frame of film has been consumed. As the fulcrum in a participatory piece of media, the audience 1) is the protagonist, whose decision to engage with a documentary is 2) a product of their desire (or need) to learn more about a topic or perspective, and so, they 3) change their circumstances by placing themselves into a situation that will allow them to watch the documentary in question. This is part of the audience’s 4) attempt to accomplish their goal — reach an increased state of enlightenment.

In this participatory model, the audience experience transitions into the hands of the filmmaker at the fifth point in Harmon’s story embryo. The filmmaker, then, serves as a knowledgeable interlocutor, a guide, whose chief responsibility is to facilitate the final four stages in the audience’s journey. In some documentaries, this role is filled in a rather literal way through the introduction of an on-screen guide — Brian Cox, Carl Sagan, Neil DeGrasse Tyson, and so on, serve as excellent examples. Such guides do not necessarily need to appear on-screen, however. They might only be presented as a disembodied voice (the narrator), speaking to the audience but never identifying themselves directly. Alternatively, they might not appear in any identifiable form whatsoever: a documentary with neither host nor narrator remains the product of its creator who, whether made manifest or not, remains the audience’s guide. As Alexander MacKendrick once put it, ‘what a film director really directs is his audience’s attention’. 11

This is particularly true of the filmmaker-scholar, whose fundamental role is that of a guide. Because of this, points five to eight of Harmon’s story embryo suggest you should not set out to guide the audience along a straightforward trajectory. Rather, you should first endeavour to lead the audience to a point where they 5) think they have found what they desire; enlightenment that superficially satisfies. In a documentary about the battles of the Second World War, for instance, an audience might reasonably expect, from an early stage, to have increased their knowledge about the mechanics and tactics of battle. The audience should thus have this desire validated by the filmmaker.

However, the documentary should then seek to 6) problematise the audience’s expectations by presenting a deeper intellectual experience than the audience could have anticipated at the outset. After a discussion about battlefield tactics, the documentary might then begin to explore the human cost of conflict; this point in the film, then, should open the audience up to new intellectual possibilities beyond those they initially imagined when they first engaged with the piece. This ever-deepening intellectual discourse ultimately 7) resolves the problematisation of the previous point; the acquisition of deeper and more sophisticated knowledge or modes of thinking should come to self-evidently justify the unimagined places the filmmaker has taken the audience. By the end of the film, the audience 8) should exit the process changed. Not only has your film helped the audience to increase their store of knowledge, as they had originally hoped, it should also have increased their understanding of the subject in ways they had not previously anticipated.

A poorly constructed documentary is one that fails to challenge its audience. This would, according to Harmon’s model, vastly reduce a film’s ability to impact the viewer. As such, point six, the intellectual pivot, should be of great structural importance to you.

In Wonder of the Universe (2011), the challenge moment occurs when Brian Cox addresses the inevitability of the universe’s end. The philosophical questions raised by this moment, and the implications for the value we attach to life, are potentially astounding. Cox, however, reassures his audience through a follow-up discussion: a doomed universe is still a marvel, even if its end can be predicted. That something reaches a conclusion, Cox suggests, does not reduce its beauty or significance12. In Harmon’s parlance, the audience suffers, they recover, and exit the film in a changed state (more enlightened).

Of course, point six in this model (the problematising pivot) should not replace a clear statement of intent (or thesis) presented at the outset of a documentary. As with an academic paper or monograph, the point of a film should be clear to the audience from an early stage. Point six, however, should serve as the moment at which some unexpected depth, or intellectual inquiry required to prove that thesis, should occur. The following discussion (point seven), should then serve as a form of intellectual reconciliation; enlightenment should follow problematisation. The thesis of a given documentary may, in its own right, offer surprises or challenge conventional wisdom, but Harmon’s story embryo requires a deeper intellectual pivot, needed to prove an already disruptive thesis, which will set the stage for a keystone discussion.

Harmon’s story embryo essentially streamlines Joseph Campbell’s ‘Hero’s Journey’. When used in relation to the documentary, however, it suggests that half of the experience is controlled directly by the audience. Whilst the audience is vital in any form of participatory media, this does create a misleading impression about the balance between the agency of the filmmaker and the audience. As a result, a further refinement — the documentary embryo — is required to describe documentary structure more accurately:

- By watching a documentary film, the audience makes the decision to embark on a quest towards enlightenment and so initiates a participatory experience (watching a documentary).

- On that quest they meet a guide (the filmmaker or their proxy) who helps them to discover the types of information they expected to learn.

- A deeper intellectual process then reveals new information, or a new perspective which complicates the audience’s view of the subject.

- That complication is then intellectually resolved, and the audience’s understanding is thus deepened in a way they might not have expected at the outset.

- The intellectual process is then brought to a close, reconciling the audience’s pre-existing perspective with the knowledge they have newly acquired. The film’s principal ideas are brought to a conclusion, which leaves the audience satisfied that their quest was not only worthwhile but deeper than they anticipated.

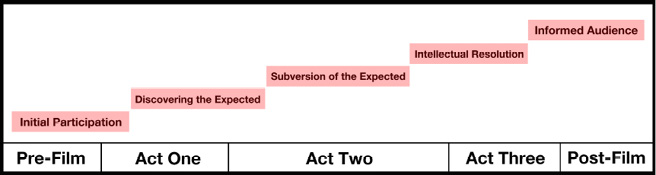

Superimposed onto a three-act structure, the participatory documentary structure can be visualised thus:

Fig. 57. The documentary embryo overlaid onto the three act structure.

Of course, rules (and structural models) can be challenged. Before disregarding the documentary embryo, however, we would encourage you to consider seriously the logic of its structure. Breaking rules can have positive results, but they can leave viewers disorientated and, if not handled well, disgruntled. Mark Cousins’ experimental documentary Atomic: Living in Dread and Promise (2015) offers neither an on-screen guide nor a narrator, a reality that is complicated by only a small amount of incidental dialogue which does not articulate a clear message or narrative. In spite of this, its problematising pivot is clear and satisfying: after significant immersion in the horrors of the atomic age, images of MRI machines and other peaceful, constructive uses of nuclear technology, challenge the viewer. The result is a film that underlines the dangers of nuclear technology even as it acknowledges the good that can come from it. Horror is thus tinged, as the film’s subtitle promises, with promise. The complexity of the nuclear question is therefore established in the minds of the audience, as the three-act structure collides with a participatory model of audience engagement.13

The On-Screen Protagonist — The Journey

Whilst the audience can certainly serve as an abstract model for the protagonist, there are more conventional opportunities to apply character-driven narrative models to the medium. By building a documentary around the experiences of an individual (or small group), be they the filmmaker or a third party, an on-screen protagonist will naturally emerge. In the case of a third-party subject, such as a historic or contemporary figure, narrative models rooted in Campbell’s ‘Hero’s Journey’ and Harmon’s story embryo prove to be particularly useful.

In Banksy’s Exit through the Gift Shop (2010), a protagonist-centred structure allows for the commercialisation of the street-art movement to be explored through biography. In the film, Thierry Guetta is 1) identified early-on as the film’s protagonist. He has 2) a desire to make a valuable contribution to the street-art community. As a result, he 3) reinvents himself to become its principal documentarian, 4) pursuing the ever-elusive Banksy to ensure that he captures a complete record of the movement’s most important figures. Over time, 5) Guetta and Banksy develop a friendship which leads the artist to invite Guetta to produce a documentary about the movement, but, as Banksy discovers, 6) Guetta was woefully incapable of creating a watchable film and, as a result, Banksy sidelines him from the project. Responding to Banksy’s suggestion that he produce some art of his own, Guetta (7) hatches a plan to become a self-made street-art phenomenon. In spite of a lack of artistic skill, he uses his connections in the field to launch his new career and, in the process (8) reinvents himself. By the end of the film, Guetta has graduated from filmmaker to a leading light in the field he once documented; his unsuitability for either role serves a warning about the thin line that can separate hype from substance.14 Like so many dramatic films, Exit through the Gift Shop relies heavily upon a familiar protagonist-centric narrative.

By employing a familiar narrative structure that hits each of the major pivots described by Harmon’s story embryo, Banksy no doubt over-simplified much about Guetta’s life, but the result is a compelling narrative which allowed for the pursuit of a deeper truth about the commercialisation of street art. Still, ethical questions abound, not the least of which is the extent to which filmmakers should bend or shape their subjects to fit a pre-determined structure. The answer to this quandary is simple: if a subject’s life does not fit a recognised narrative model (and, therefore, is unlikely to contain the tensions and narrative shifts that will arrest an audience’s interest), they should not be employed as a protagonist. In other words, do not make your subjects fit a structure for which their lived experiences are ill-suited. When a filmic structure fails to enhance one’s analysis of a subject, a different approach should be taken. Appealing to the documentary embryo, and centring a film on the audience, may suffice but in cases where a single subject (or small group) sits at the heart of a film, audiences might well expect that subject to be explored in a familiar way.

In such instances, the filmmaker (or a proxy, acting on their behalf) might serve as a suitable protagonist around which a familiar and engaging structure can be woven, which intersects with the chosen subject. Journeys of intellectual discovery are common, with on-screen hosts taking their audiences on journeys centred on personal quests of discovery or self-improvement.

‘The Journey’ is common in a wide variety of documentaries. Indeed, it is so common that it is often used in trite, unimaginative ways: after identifying 1) themselves as the film’s protagonist and 2) articulating their desire to learn about subject X, the on-screen host can 3) move out of their traditional lives in order to start a journey of 4) discovery about the subject at hand. Along the way they will 5) start to achieve their goal, learning much, but they will 6) also discover unexpected truths. Ultimately, however, they will 7) reconcile those discoveries with their pre-existing expectations to arrive at a new truth and, consequently, 8) leave the process with a deeper understanding of their subject.

Consider the above abstraction and compare it to any number of broadcast documentaries, particularly those in which a non-expert, typically a celebrity of some kind, goes on a journey of discovery, perhaps to uncover the truth of their family history. In many cases, this structure is used in poor-quality or mediocre documentaries, but the device itself serves to effectively dramatize events and studies which, otherwise, might fail to retain the interest of a broad audience. But any structure is only as valuable as its implementation, and whilst there are innumerable examples of ‘The Journey’ that are derivative, unimaginative, and uninteresting, these are problems with individual productions, not necessarily the structure itself.

‘The Journey’ needs to be a narrative that is worth telling in its own right. Authenticity and honesty are vital to the successful use of this device, and genuine autobiography, which brings out deeper themes in a study, can add compelling new insights to an intellectual discourse. Broadcast documentaries in which on-screen hosts stage aspects of their journey for the sake of creating a narrative can alienate discerning viewers. More effective than a staged and dishonest journey would be a complete reappraisal of how the rules of cinematic narrative can best be used to engage an audience with the subject at hand.

Structural models must be used in imaginative and appropriate ways to pursue a deeper, more meaningful discourse. ‘The Journey’ is an excellent example of a documentary trope that has been overused in derivative ways. British documentarian Louis Theroux has used it throughout his career to varying degree of success. In My Scientology Movie (2015) he succeeds to a greater degree than he does in many (though certainly not all) of his prior productions. Because Theroux is documenting a group in whom he has a genuine interest and in whose religion he has a solid intellectual grounding, his journey in that film feels real. The result is a high-quality production in which Theroux’s growing discomfort carries significant intellectual weight. The audience is able to believe that Theroux is going through a (re)formative process.15

The three-act structure, story embryo, and its derivative, the documentary embryo, are devices that are only as effective as their implementation. Utilising a structural model does not guarantee that an effective film will be produced, though it may increase the likelihood that this will occur. Likewise, disregarding such structures will not necessarily lead to a poor-quality product; nonetheless, thoroughly understanding the structures or narrative conventions most audiences expect (and even demand) will make it easier to challenge dominant narrative models in the documentary space.

1 Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Third Edition (New York: Pantheon Books, 1949; reprint, Novato: New World Library, 2008), pp. 1–40.

2 This breakdown of the protagonist structure is based upon Dan Harmon’s ‘Story Circle’, which will discussed extensively in the next chapter. See Dan Harmon, ‘Story Structure’, Channel 101 Wiki, http://channel101.wikia.com/wiki/Story_Structure_101:_Super_Basic_Shit

3 Roger and Me. Directed by Michael Moore. Burbank: Warner Bros., 1989.

4 Yorke, Into the Woods, pp. ix–xiv.

5 Wonders of the Solar System. London: BBC, 2010.

6 Stuart L. Brown, foreword to The Heroes Journey: Joseph Campbell on his Life and Work by Joseph Campbell (New York: New World Library, 2003), pp. vii–xii; Yorke, Into the Woods, pp. 33–34.

7 Dan Harmon, ‘Story Structure’, Channel 102 Wiki, http://channel101.wikia.com/wiki/Story_Structure_102:_Pure,_Boring_Theory

8 Capitalism: A Love Story. Directed by Michael Moore. Los Angeles: The Weinstein Company, 2009.

9 Dan Harmon, ‘Story Structure’, Channel 104 Wiki, http://channel101.wikia.com/wiki/Story_Structure_104:_The_Juicy_Details

10 The Godfather. Directed by Francis Ford Coppola. Hollywood: Paramount Pictures, 1972; Annie Hall. Directed by Woody Allen. Los Angeles: United Artists, 1977; Raiders of the Lost Ark. Directed by Steven Spielberg. Hollywood: Paramount Pictures, 1981; Amélie. Directed by Jean-Pierre Jeunet. UGC: Neuilly-sur-Seine, 2001.

11 Alexander Mackendrick, On Filmmaking (London: Faber & Faber, 2006), p. 200.

12 Wonders of the Universe. London: BBC, 2011.

13 Atomic: Living in Dread and Promise. Directed by Mark Cousins. London: BBC, 2015.

14 Exit through the Gift Shop. Directed by Banksy. London: Revolver Entertainment, 2010.

15 My Scientology Movie. Digital Stream. Directed by John Dower. London: BBC Films, 2015.