1.8: Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822)

- Page ID

- 102493

Percy Bysshe Shelley was probably the most intellectual of all the Romantic poets; he was certainly one of the most well-educated. He was a non-conformist thinker, a philosopher, and a rebel. All of these characteristics join in his theory of poetry and poetic output, with their commitment to radical politics and their visionary idealism influenced by Platonism. Like Byron, Shelley was born into an aristocratic family, was in line to inherit a large estate, and was secured of a seat in the House of Lords in Parliament. Instead, Shelley became the river that made its own banks.

This independence of both thought and action appeared when Shelley wrote a pamphlet On the Necessity of Atheism while at Oxford. Rather than leading to intellectual debate as he expected, this pamphlet led to his being expelled. At the age of nineteen, Shelley eloped with Harriet Westbrook, the daughter of a stable hand. He pursued his intellectual and political interests by befriending the socialist philosopher William Godwin (1756-1836) and publishing Queen Mab, a utopian poem. At the grave of Godwin’s deceased wife Mary Wollstonecraft, Shelley also wooed their daughter Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin. The two eloped to Europe, Shelley’s wife Harriet having refused to join them. In 1816, Harriet Shelley committed suicide by drowning herself in the shallow end of the Serpentine River; she was apparently pregnant with another man’s child. Mary  Godwin and Percy Bysshe had lost two children of their own before they married upon Harriet’s death. Percy Bysshe lost custody of his and Harriet’s two children due to his reputation.

Godwin and Percy Bysshe had lost two children of their own before they married upon Harriet’s death. Percy Bysshe lost custody of his and Harriet’s two children due to his reputation.

Percy Bysshe and Mary Shelley traveled throughout Italy where Percy Bysshe wrote the bulk of his most famous works. In 1822, he drowned while sailing his schooner Don Juan (named after a poem by Byron) from Livorno to Lerici. He may have desired this death, disappointed and disaffected with the “triumph of life” over vision. He certainly seems to have predicted this mode of death in Adonais, an elegy he wrote for John Keats: “My spirit’s bark is driven,/ Far from the shore, far from the trembling throng/ Whose sails were never to the tempest given” (489-91).

It is important to consider the breadth and height of Shelley’s demands on poetry. He had great expectations from poetry and from poets, whom he described as power figures; for poets channel the power of the source itself (rather than the dominion). He therefore presents poets as the channels of power for change, for freedom, for humanity. His The Defense of Poetry takes the challenge Plato made when ejecting poets from his Republic. In it, Shelley describes poets as the best men with the best thoughts who see the seeds of the future cast upon the present. As such, they are the “unacknowledged legislators of the world.”

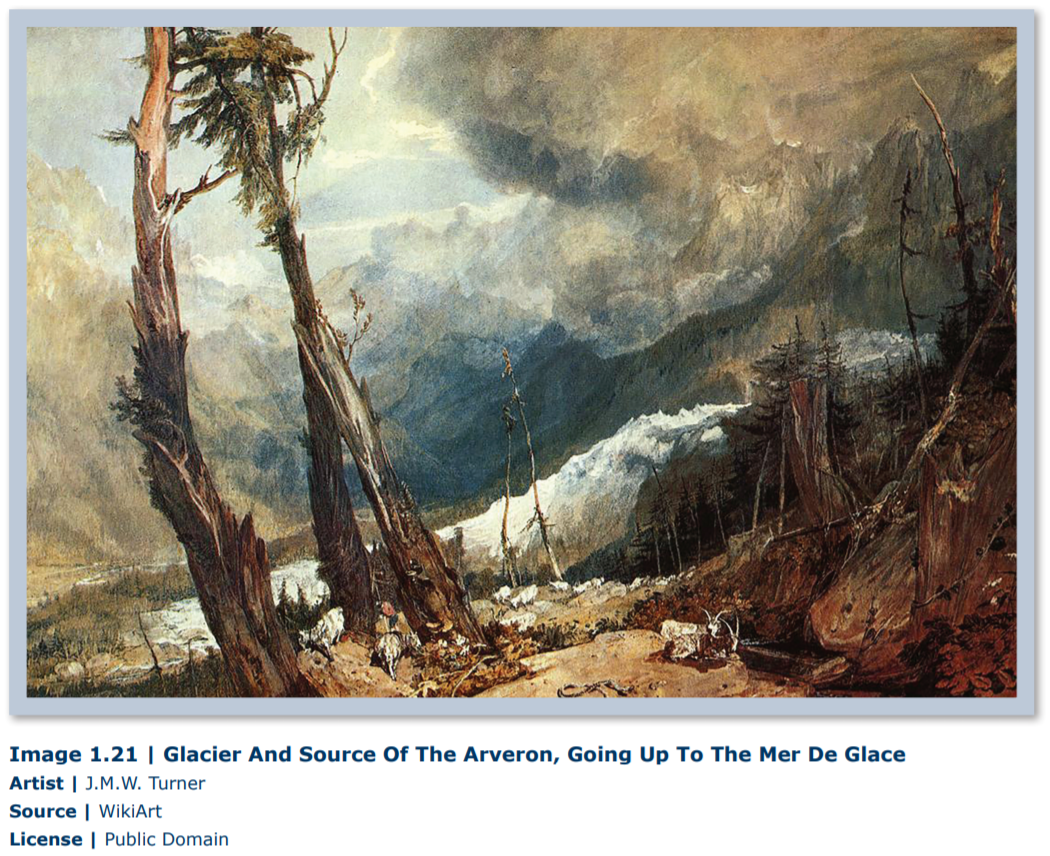

1.11.1: “Mont Blanc”

Lines Written in the Vale of Chamouni

I

The everlasting universe of things

Flows through the mind, and rolls its rapid waves,

Now dark—now glittering—now reflecting gloom—

Now lending splendour, where from secret springs

The source of human thought its tribute brings

Of waters—with a sound but half its own,

Such as a feeble brook will oft assume,

In the wild woods, among the mountains lone,

Where waterfalls around it leap for ever,

Where woods and winds contend, and a vast river

Over its rocks ceaselessly bursts and raves.

II

Thus thou, Ravine of Arve—dark, deep Ravine—

Thou many-colour’d, many-voiced vale,

Over whose pines, and crags, and caverns sail

Fast cloud-shadows and sunbeams: awful scene,

Where Power in likeness of the Arve comes down

From the ice-gulfs that gird his secret throne,

Bursting through these dark mountains like the flame

Of lightning through the tempest;—thou dost lie,

Thy giant brood of pines around thee clinging,

Children of elder time, in whose devotion

The chainless winds still come and ever came

To drink their odours, and their mighty swinging

To hear—an old and solemn harmony;

Thine earthly rainbows stretch’d across the sweep

Of the aethereal waterfall, whose veil

Robes some unsculptur’d image; the strange sleep

Which when the voices of the desert fail

Wraps all in its own deep eternity;

Thy caverns echoing to the Arve’s commotion,

A loud, lone sound no other sound can tame;

Thou art pervaded with that ceaseless motion,

Thou art the path of that unresting sound—

Dizzy Ravine! and when I gaze on thee

I seem as in a trance sublime and strange

To muse on my own separate fantasy,

My own, my human mind, which passively

Now renders and receives fast influencings,

Holding an unremitting interchange

With the clear universe of things around;

One legion of wild thoughts, whose wandering wings

Now float above thy darkness, and now rest

Where that or thou art no unbidden guest,

In the still cave of the witch Poesy,

Seeking among the shadows that pass by

Ghosts of all things that are, some shade of thee,

Some phantom, some faint image; till the breast

From which they fled recalls them, thou art there!

III

Some say that gleams of a remoter world

Visit the soul in sleep, that death is slumber,

And that its shapes the busy thoughts outnumber

Of those who wake and live.—I look on high;

Has some unknown omnipotence unfurl’d

The veil of life and death? or do I lie

In dream, and does the mightier world of sleep

Spread far around and inaccessibly

Its circles? For the very spirit fails,

Driven like a homeless cloud from steep to steep

That vanishes among the viewless gales!

Far, far above, piercing the infinite sky,

Mont Blanc appears—still, snowy, and serene;

Its subject mountains their unearthly forms

Pile around it, ice and rock; broad vales between

Of frozen floods, unfathomable deeps,

Blue as the overhanging heaven, that spread

And wind among the accumulated steeps;

A desert peopled by the storms alone,

Save when the eagle brings some hunter’s bone,

And the wolf tracks her there—how hideously

Its shapes are heap’d around! rude, bare, and high,

Ghastly, and scarr’d, and riven.—Is this the scene

Where the old Earthquake-daemon taught her young

Ruin? Were these their toys? or did a sea

Of fire envelop once this silent snow?

None can reply—all seems eternal now.

The wilderness has a mysterious tongue

Which teaches awful doubt, or faith so mild,

So solemn, so serene, that man may be,

But for such faith, with Nature reconcil’d;

Thou hast a voice, great Mountain, to repeal

Large codes of fraud and woe; not understood

By all, but which the wise, and great, and good

Interpret, or make felt, or deeply feel.

IV

The fields, the lakes, the forests, and the streams,

Ocean, and all the living things that dwell

Within the daedal earth; lightning, and rain,

Earthquake, and fiery flood, and hurricane,

The torpor of the year when feeble dreams

Visit the hidden buds, or dreamless sleep

Holds every future leaf and flower; the bound

With which from that detested trance they leap;

The works and ways of man, their death and birth,

And that of him and all that his may be;

All things that move and breathe with toil and sound

Are born and die; revolve, subside, and swell.

Power dwells apart in its tranquillity,

Remote, serene, and inaccessible:

And this, the naked countenance of earth,

On which I gaze, even these primeval mountains

Teach the adverting mind. The glaciers creep

Like snakes that watch their prey, from their far fountains,

Slow rolling on; there, many a precipice

Frost and the Sun in scorn of mortal power

Have pil’d: dome, pyramid, and pinnacle,

A city of death, distinct with many a tower

And wall impregnable of beaming ice.

Yet not a city, but a flood of ruin

Is there, that from the boundaries of the sky

Rolls its perpetual stream; vast pines are strewing

Its destin’d path, or in the mangled soil

Branchless and shatter’d stand; the rocks, drawn down

From yon remotest waste, have overthrown

The limits of the dead and living world,

Never to be reclaim’d. The dwelling-place

Of insects, beasts, and birds, becomes its spoil;

Their food and their retreat for ever gone,

So much of life and joy is lost. The race

Of man flies far in dread; his work and dwelling

Vanish, like smoke before the tempest’s stream,

And their place is not known. Below, vast caves

Shine in the rushing torrents’ restless gleam,

Which from those secret chasms in tumult welling

Meet in the vale, and one majestic River,

The breath and blood of distant lands, for ever

Rolls its loud waters to the ocean-waves,

Breathes its swift vapours to the circling air.

V

Mont Blanc yet gleams on high:—the power is there,

The still and solemn power of many sights,

And many sounds, and much of life and death.

In the calm darkness of the moonless nights,

In the lone glare of day, the snows descend

Upon that Mountain; none beholds them there,

Nor when the flakes burn in the sinking sun,

Or the star-beams dart through them. Winds contend

Silently there, and heap the snow with breath

Rapid and strong, but silently! Its home

The voiceless lightning in these solitudes

Keeps innocently, and like vapour broods

Over the snow. The secret Strength of things

Which governs thought, and to the infinite dome

Of Heaven is as a law, inhabits thee!

And what were thou, and earth, and stars, and sea,

If to the human mind’s imaginings

Silence and solitude were vacancy?

1.11.2: “England in 1819”

An old, mad, blind, despised, and dying King;

Princes, the dregs of their dull race, who flow

Through public scorn,—mud from a muddy spring;

Rulers who neither see nor feel nor know,

But leechlike to their fainting country cling

Till they drop, blind in blood, without a blow.

A people starved and stabbed in th’ untilled field;

An army, whom liberticide and prey

Makes as a two-edged sword to all who wield;

Golden and sanguine laws which tempt and slay;

Religion Christless, Godless—a book sealed;

A senate, Time’s worst statute, unrepealed—

Are graves from which a glorious Phantom may

Burst, to illumine our tempestuous day.

1.11.3: “Ode to the West Wind”

I

O wild West Wind, thou breath of Autumn’s being,

Thou, from whose unseen presence the leaves dead

Are driven, like ghosts from an enchanter fleeing,

Yellow, and black, and pale, and hectic red,

Pestilence-stricken multitudes: O thou,

Who chariotest to their dark wintry bed

The winged seeds, where they lie cold and low,

Each like a corpse within its grave, until

Thine azure sister of the Spring shall blow

Her clarion o’er the dreaming earth, and fill

(Driving sweet buds like flocks to feed in air)

With living hues and odours plain and hill:

Wild Spirit, which art moving everywhere;

Destroyer and preserver; hear, oh hear!

II

Thou on whose stream, mid the steep sky’s commotion,

Loose clouds like earth’s decaying leaves are shed,

Shook from the tangled boughs of Heaven and Ocean,

Angels of rain and lightning: there are spread

On the blue surface of thine aëry surge,

Like the bright hair uplifted from the head

Of some fierce Maenad, even from the dim verge

Of the horizon to the zenith’s height,

The locks of the approaching storm. Thou dirge

Of the dying year, to which this closing night

Will be the dome of a vast sepulchre,

Vaulted with all thy congregated might

Of vapours, from whose solid atmosphere

Black rain, and fire, and hail will burst: oh hear!

III

Thou who didst waken from his summer dreams

The blue Mediterranean, where he lay,

Lull’d by the coil of his crystalline streams,

Beside a pumice isle in Baiae’s bay,

And saw in sleep old palaces and towers

Quivering within the wave’s intenser day,

All overgrown with azure moss and flowers

So sweet, the sense faints picturing them!

Thou For whose path the Atlantic’s level powers

Cleave themselves into chasms, while far below

The sea-blooms and the oozy woods which wear

The sapless foliage of the ocean, know

Thy voice, and suddenly grow gray with fear,

And tremble and despoil themselves: oh hear!

IV

If I were a dead leaf thou mightest bear;

If I were a swift cloud to fly with thee;

A wave to pant beneath thy power, and share

The impulse of thy strength, only less free

Than thou, O uncontrollable! If even

I were as in my boyhood, and could be

The comrade of thy wanderings over Heaven,

As then, when to outstrip thy skiey speed

Scarce seem’d a vision; I would ne’er have striven

As thus with thee in prayer in my sore need.

Oh, lift me as a wave, a leaf, a cloud!

I fall upon the thorns of life! I bleed!

A heavy weight of hours has chain’d and bow’d

One too like thee: tameless, and swift, and proud.

V

Make me thy lyre, even as the forest is:

What if my leaves are falling like its own!

The tumult of thy mighty harmonies

Will take from both a deep, autumnal tone,

Sweet though in sadness. Be thou, Spirit fierce,

My spirit! Be thou me, impetuous one!

Drive my dead thoughts over the universe

Like wither’d leaves to quicken a new birth!

And, by the incantation of this verse,

Scatter, as from an unextinguish’d hearth

Ashes and sparks, my words among mankind!

Be through my lips to unawaken’d earth

The trumpet of a prophecy! O Wind,

If Winter comes, can Spring be far behind?