4.5: Henry Fielding's The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling (excerpt)

- Page ID

- 168437

Henry Fielding was a strong student of the classics at Eton. This scholarship would later give design to his novels, works he first described as “comic prose epics,” that is, hybrids that openly declared their artfulness. He took the novel genre into new realms as openly serious and a valuable contribution to the English literary tradition. After graduating from Eton, Fielding entered society under the auspices of his cousin Mary Wortley Montagu, to whom he dedicated his first comedy Love in Several Masques (1728). He followed this with numerous other works, including translations, satires, comedies, burlesques (absurd imitations), and farces (broad comedies). His preface to the burlesque The Tragedy of Tragedies: Or, The Life and Death of Tom Thumb the Great (published in 1731) justified his using “lesser” genres like the burlesque. He suggested that his “tragedy” conformed to the tragic dimensions of the epic and exemplified the manner in which tragedies necessarily were written in his unheroic day and age—as comedies and parodies. He thus brought to the drama the shift in genre that Pope brought to poetry with his Rape of the Lock.

Henry Fielding was a strong student of the classics at Eton. This scholarship would later give design to his novels, works he first described as “comic prose epics,” that is, hybrids that openly declared their artfulness. He took the novel genre into new realms as openly serious and a valuable contribution to the English literary tradition. After graduating from Eton, Fielding entered society under the auspices of his cousin Mary Wortley Montagu, to whom he dedicated his first comedy Love in Several Masques (1728). He followed this with numerous other works, including translations, satires, comedies, burlesques (absurd imitations), and farces (broad comedies). His preface to the burlesque The Tragedy of Tragedies: Or, The Life and Death of Tom Thumb the Great (published in 1731) justified his using “lesser” genres like the burlesque. He suggested that his “tragedy” conformed to the tragic dimensions of the epic and exemplified the manner in which tragedies necessarily were written in his unheroic day and age—as comedies and parodies. He thus brought to the drama the shift in genre that Pope brought to poetry with his Rape of the Lock.

Fielding extended this shift to prose in his two parodies of Samuel Richardson’s epistolary novel Pamela: Or, Virtue Rewarded (1740). Fielding’s An Apology for the Life of Mrs. Shamela Andrews (1741) and Joseph Andrews, and of His Friend Mr. Abraham Adams parody Richardson’s work in which a libertine kidnaps a servant in order to “have his way” with her. The titillating situation, and Pamela’s ultimate reward for protecting her virtue (even as she skates between truth-telling and lying to fend off the antagonist Mr. B.), highlighted problematic qualities of the developing novel as genre, such as its depicting wickedness in great detail in order to convert the reader to goodness (as Defoe does in Moll Flanders).

Fielding used his experience as a playwright to carefully design his novels. For example, in Joseph Andrews, he carefully plotted out individual scenes that have clear beginnings, middles, and ends; also, he gave clearly-identifiable speech to individual characters. He developed these strengths further in his comic novel The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling (1749). These works include a range of different characters, from merchants and lawyers to aristocrats, landed gentry, and their servants. Fielding himself appears as a character in these works; in Joseph Andrews, he clearly identifies himself as the creator of fiction—not masquerading as history or fact—in order to reveal Truth. He does so because “It is a trite but true Observation, that Examples work more forcibly on the Mind than Precepts” (Joseph Andrews). He also includes the Reader as a character, characterizing the reader in multiple ways, as serious, uni-ligual, and more (in at least sixteen different ways). By doing so, he identified the novel genre with comprehensiveness, with a comprehensive range of incidents and characters, in order to convey the fullness of his society.

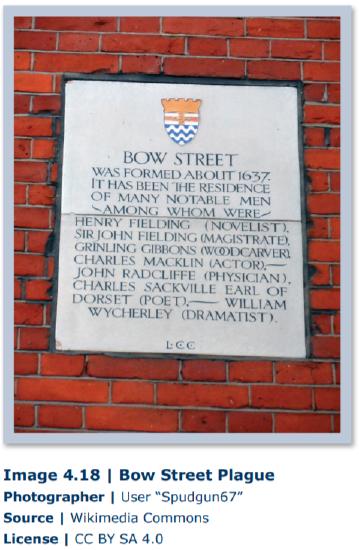

Fielding came to know his society very well indeed, writing long political essays, taking the bar in 1740, and being appointed as magistrate at Bow Street in 1748 and later as magistrate of Middlesex. His Bow Street Runners were law officers who patrolled the streets, protecting private citizens from thieves and gangs. Through his careful administration, Fielding’s police force would lead to the modern Scotland Yard.

Fielding came to know his society very well indeed, writing long political essays, taking the bar in 1740, and being appointed as magistrate at Bow Street in 1748 and later as magistrate of Middlesex. His Bow Street Runners were law officers who patrolled the streets, protecting private citizens from thieves and gangs. Through his careful administration, Fielding’s police force would lead to the modern Scotland Yard.

History of Tom Jones, a Foundling by Henry Fielding

The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling is in the Public Domain and may be read online free of cost at the Gutenberg Project.

Excerpt from History of Tom Jones, a Foundling, BOOK I. — CONTAINING AS MUCH OF THE BIRTH OF THE FOUNDLING AS IS NECESSARY OR PROPER TO ACQUAINT THE READER WITH IN THE BEGINNING OF THIS HISTORY.

Chapter i. — The introduction to the work, or bill of fare to the feast.

An author ought to consider himself, not as a gentleman who gives a private or eleemosynary treat, but rather as one who keeps a public ordinary, at which all persons are welcome for their money. In the former case, it is well known that the entertainer provides what fare he pleases; and though this should be very indifferent, and utterly disagreeable to the taste of his company, they must not find any fault; nay, on the contrary, good breeding forces them outwardly to approve and to commend whatever is set before them. Now the contrary of this happens to the master of an ordinary. Men who pay for what they eat will insist on gratifying their palates, however nice and whimsical these may prove; and if everything is not agreeable to their taste, will challenge a right to censure, to abuse, and to d—n their dinner without controul.

To prevent, therefore, giving offence to their customers by any such disappointment, it hath been usual with the honest and well-meaning host to provide a bill of fare which all persons may peruse at their first entrance into the house; and having thence acquainted themselves with the entertainment which they may expect, may either stay and regale with what is provided for them, or may depart to some other ordinary better accommodated to their taste.

As we do not disdain to borrow wit or wisdom from any man who is capable of lending us either, we have condescended to take a hint from these honest victuallers, and shall prefix not only a general bill of fare to our whole entertainment, but shall likewise give the reader particular bills to every course which is to be served up in this and the ensuing volumes.

The provision, then, which we have here made is no other than Human Nature. Nor do I fear that my sensible reader, though most luxurious in his taste, will start, cavil, or be offended, because I have named but one article. The tortoise—as the alderman of Bristol, well learned in eating, knows by much experience—besides the delicious calipash and calipee, contains many different kinds of food; nor can the learned reader be ignorant, that in human nature, though here collected under one general name, is such prodigious variety, that a cook will have sooner gone through all the several species of animal and vegetable food in the world, than an author will be able to exhaust so extensive a subject.

An objection may perhaps be apprehended from the more delicate, that this dish is too common and vulgar; for what else is the subject of all the romances, novels, plays, and poems, with which the stalls abound? Many exquisite viands might be rejected by the epicure, if it was a sufficient cause for his contemning of them as common and vulgar, that something was to be found in the most paltry alleys under the same name. In reality, true nature is as difficult to be met with in authors, as the Bayonne ham, or Bologna sausage, is to be found in the shops.

But the whole, to continue the same metaphor, consists in the cookery of the author; for, as Mr Pope tells us—

“True wit is nature to advantage drest;

What oft was thought, but ne'er so well exprest.”

The same animal which hath the honour to have some part of his flesh eaten at the table of a duke, may perhaps be degraded in another part, and some of his limbs gibbeted, as it were, in the vilest stall in town. Where, then, lies the difference between the food of the nobleman and the porter, if both are at dinner on the same ox or calf, but in the seasoning, the dressing, the garnishing, and the setting forth? Hence the one provokes and incites the most languid appetite, and the other turns and palls that which is the sharpest and keenest.

In like manner, the excellence of the mental entertainment consists less in the subject than in the author's skill in well dressing it up. How pleased, therefore, will the reader be to find that we have, in the following work, adhered closely to one of the highest principles of the best cook which the present age, or perhaps that of Heliogabalus, hath produced. This great man, as is well known to all lovers of polite eating, begins at first by setting plain things before his hungry guests, rising afterwards by degrees as their stomachs may be supposed to decrease, to the very quintessence of sauce and spices. In like manner, we shall represent human nature at first to the keen appetite of our reader, in that more plain and simple manner in which it is found in the country, and shall hereafter hash and ragoo it with all the high French and Italian seasoning of affectation and vice which courts and cities afford. By these means, we doubt not but our reader may be rendered desirous to read on for ever, as the great person just above-mentioned is supposed to have made some persons eat.

Having premised thus much, we will now detain those who like our bill of fare no longer from their diet, and shall proceed directly to serve up the first course of our history for their entertainment.

The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling is in the Public Domain and may be read online free of cost at the Gutenberg Project.