4.3: Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe (excerpt)

- Page ID

- 168431

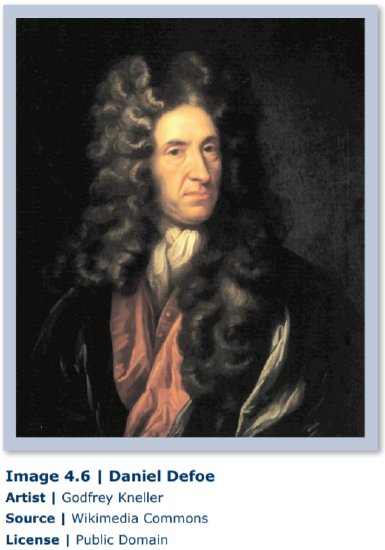

Daniel Defoe was born to James Foe, a tallow chandler and “auditor for the Butcher’s Company,” and Alice, who died when Daniel was eight. He changed his name to Defoe in 1695. He studied at the Reverend James Fisher’s school at Dorking, Surrey. As a Dissenter, Defoe could not enter either Oxford or Cambridge, so he studied instead at the Reverend Charles Morton’s small college at Newington Green. There he studied not only the classics but also modern languages, geography, and mathematics. Although expected to enter the ministry, Defoe began work as a hose-factor. To find trade goods, he traveled extensively in Europe. In 1684, he married Mary Tuffley, the daughter of a wealthy merchant, who brought with her a considerable dowry.

Daniel Defoe was born to James Foe, a tallow chandler and “auditor for the Butcher’s Company,” and Alice, who died when Daniel was eight. He changed his name to Defoe in 1695. He studied at the Reverend James Fisher’s school at Dorking, Surrey. As a Dissenter, Defoe could not enter either Oxford or Cambridge, so he studied instead at the Reverend Charles Morton’s small college at Newington Green. There he studied not only the classics but also modern languages, geography, and mathematics. Although expected to enter the ministry, Defoe began work as a hose-factor. To find trade goods, he traveled extensively in Europe. In 1684, he married Mary Tuffley, the daughter of a wealthy merchant, who brought with her a considerable dowry.

In 1685, he joined in the doomed Protestant uprising of James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth and illegitimate son of Charles II, against the Roman Catholic James II soon after Charles II’s death. Defoe may have escaped the ensuing Bloody Assizes (rebels’ trials) by fleeing abroad; he certainly received a pardon in 1687. His political position became more stable upon the accession of William III and Mary II.

His financial position was more precarious; he declared bankruptcy in 1692 after failed commercial ventures and shipping losses. Governmental appointments, including his spying for William III and Mary II, floated him. His finances saw fortune and loss, and his political appointments and activities became comparably checkered, or pragmatic. Once he turned to writing, he wrote a number of propagandist pieces, including the parodic The Shortest Way with Dissenters.

This oblique attack on the Tories caused Defoe to be arrested, convicted of seditious libel, and sentenced to pay a fine, be jailed, and be pilloried for three days. Those in the pillory could suffer the mercy of the mob, or stoning, a fate that Defoe prevented by entertaining the gathered crowds with stories. Defoe established a spy system for Robert Harley, a representative of Queen Anne’s government and became a double agent in service of England’s first Prime Minister, Robert Walpole. He published articles in both Tory and Whig journals, articles for and against both parties. He also published over 500 works, ranging from poems to early novels. His failing finances continued to dog him. In 1730, he left home to hide from a creditor and died alone in a rented room. His life ran like his novels, in which movement seems constant. But when movement stops, as when Moll Flanders is held in Newgate Prison, then one has time for reflection and conscience. Because death stops all, Defoe reminds us to be serious: “What is left ’tis hoped will not offend the chastest reader or the modest hearer; and as the best use is made even of the worst story, the moral ’tis hoped will keep the reader serious” (Moll Flanders).

Robinson Crusoe is in the Public Domain and may be read online free of cost at the Gutenberg Project.

CHAPTER I: HOW ROBINSON FIRST WENT TO SEA; AND HOW HE WAS SHIPWRECKED

Long, long ago, before even your grandfather’s father was born, there lived in the town of York a boy whose name was Robinson Crusoe. Though he never even saw the sea till he was quite a big boy, he had always wanted to be a sailor, and to go away in a ship to visit strange, foreign, far-off lands; and he thought that if he could only do that, he would be quite happy.

But his father wanted him to be a lawyer, and he often talked to Robinson, and told him of the terrible things that might happen to him if he went away, and how people who stopped at home were always the happiest. He told him, too, how Robinson’s brother [Pg 2]had gone away, and had been killed in the wars.

So Robinson promised at last that he would give up wanting to be a sailor. But in a few days the longing came back as bad as ever, and he asked his mother to try to coax his father to let him go just one voyage. But his mother was very angry, and his father said, ‘If he goes abroad he will be the most miserable wretch that ever was born. I can give no consent to it.’

Robinson stopped at home for another year, till he was nineteen years old, all the time thinking and thinking of the sea. But one day when he had gone on a visit to Hull, a big town by the sea, to say good-bye to one of his friends who was going to London, he could not resist the chance. Without even sending a message to his father and mother, he went on board his friend’s ship, and sailed away.

But as soon as the wind began to blow and the waves to rise, poor Robinson was very frightened and sea-sick, and he said to himself[Pg 3] that if ever he got on shore he would go straight home and never again leave it.

He was very solemn till the wind stopped blowing. His friend and the sailors laughed at him, and called him a fool, and he very soon forgot, when the weather was fine and the sun shining, all he had thought about going back to his father and mother.

But in a few days, when the ship had sailed as far as Yarmouth Roads on her way to London, they had to anchor, and wait for a fair wind. In those days there were no steamers, and vessels had only their sails to help them along; so if it was calm, or the wind blew the wrong way, they had just to wait where they were till a fair wind blew.

Whilst they lay at Yarmouth the weather became very bad, and there was a great storm. The sea was so heavy and Robinson’s ship was in such danger, that at last they had to cut away the masts in order to ease her and to stop her from rolling so terribly. The Captain fired guns to show that his [Pg 4]ship wanted help. So a boat from another ship was lowered, and came with much difficulty and took off Robinson and all the crew, just before their vessel sank; and they got ashore at last, very wet and miserable, having lost all their clothes except what they had on.

But Robinson had some money in his pocket, and he went on to London by land, thinking that if he returned home now, people would laugh at him.

In London he made friends with a ship’s captain, who had not long before come home from a voyage to the Guinea Coast, as that part of Africa was then called; and the Captain was so pleased with the money he had made there, that he easily persuaded Robinson to go with him on his next voyage.

So Robinson took with him toys, and beads, and other things, to sell to the natives in Africa, and he got there, in exchange for these things, so much gold dust that he thought he was soon going in that way to make his fortune.

[Pg 5]

And therefore he went on a second voyage.

But this time he was not so lucky, for before they reached the African Coast, one morning, very early, they sighted another ship, which they were sure was a Pirate. So fast did this other vessel sail, that before night she had come up to Robinson’s ship, which did not carry nearly so many men nor so many guns as the Pirate, and which therefore did not want to fight; and the pirates soon took prisoner Robinson and all the crew of his ship who were not killed, and made slaves of them.

The Pirate captain took Robinson as his own slave, and made him dig in his garden and work in his house. Sometimes, too, he made him look after his ship when she was in port, but he never took him away on a voyage.

For two years Robinson lived like this, very unhappy, and always thinking how he might escape.

At last, when the Captain happened one time to be at home longer than usual, he began to go out fishing in a boat two or three [Pg 6]times a week, taking Robinson, who was a very good fisher, and a black boy named Xury, with him.

One day he gave Robinson orders to put food and water, and some guns, and powder and shot, on a big boat that the pirates had taken out of an English ship, and to be ready to go with him and some of his friends on a fishing trip.

But at the last moment the Captain’s friends could not come, and so Robinson was told to go out in the boat with one of the Captain’s servants who was not a slave, and with Xury, to catch fish for supper.

Then Robinson thought that his chance to escape had come.

He spoke to the servant, who was not very clever, and persuaded him to put more food and water on the boat, for, said Robinson, ‘we must not take what was meant for our master.’ And then he got the servant to bring some more powder and shot, because, Robinson said, they might as well kill some birds to eat.

[Pg 7]

When they had gone out about a mile, they hauled down the sail and began to fish. But Robinson pretended that he could not catch anything there, and he said that they ought to go further out. When they had gone so far that nobody on shore could see what they were doing, Robinson again pretended to fish. But this time he watched his chance, and when the servant was not looking, came behind him and threw him overboard, knowing that the man could swim so well that he could easily reach the land.

Then Robinson sailed away with Xury down the coast to the south. He did not know to what country he was steering, but cared only to get away from the pirates, and to be free once more.

Long days and nights they sailed, sometimes running in close to the land, but they were afraid to go ashore very often, because of the wild beasts and the natives. Many times they saw great lions come roaring down on to the beach, and once Robinson [Pg 8]shot one that he saw lying asleep, and took its skin to make a bed for himself on the boat.

At last, after some weeks, when they had got south as far as the great cape that is called Cape de Verde, they saw a Portuguese vessel, which took them on board. It was not easy for Robinson to tell who he was, because he could not talk Portuguese, but everybody was very kind to him, and they bought his boat and his guns and everything that he had. They even bought poor Xury, who, of course, was a black slave, and could be sold just like a horse or a dog.

So, when they got to Brazil, where the vessel was bound, Robinson had enough money to buy a plantation; and he grew sugar and tobacco there for four years, and was very happy and contented for a time, and made money.

Once Robinson shot a lion that he saw lying asleep

But he could never be contented for very long. So when some of his neighbours asked him if he would go in a ship to the Guinea Coast to get slaves for them, he went, only [Pg 9]making a bargain that he was to be paid for his trouble, and to get some of the slaves to work on his plantation when he came back.

Twelve days after the ship sailed, a terrible storm blew, and they were driven far from where they wanted to go. Great, angry, foaming seas broke over the deck, sweeping everything off that could be moved, and a man and a boy were carried overboard and drowned. No one on the ship expected to be saved.

This storm was followed by another, even worse. The wind howled and roared through the rigging, and the weather was thick with rain and flying spray.

Then early one morning land was dimly seen through the driving rain, but almost at once the vessel struck on a sand-bank. In an instant the sails were blown to bits, and flapped with such uproar that no one could hear the Captain’s orders. Waves poured over the decks, and the vessel bumped on the sand so terribly that the [Pg 10]masts broke off near the deck, and fell over the side into the sea.

With great difficulty the only boat left on the ship was put in the water, and everybody got into her. They rowed for the shore, hoping to get perhaps into some bay, or to the mouth of a river, where the sea would be quiet.

But before they could reach the land, a huge grey wave, big like the side of a house, came foaming and thundering up behind them, and before any one could even cry out, it upset the boat, and they were all left struggling in the water.

Robinson was a very good swimmer, but no man could swim in such a sea, and it was only good fortune that brought him at last safely to land. Big wave after big wave washed him further and further up the beach, rolling him over and over, once leaving him helpless, and more than half-drowned, beside a rock.

But before the next wave could come up, perhaps to drag him back with it into the [Pg 11]sea, he was able to jump up and run for his life.

And so he got safely out of the reach of the water, and lay down upon the grass. But of all on board the ship, Robinson was the only one who was not drowned.

[Pg 12]