4.5: Music of George Frideric Handel (1685-1759)

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 76196

- Clark, Heflin, Kluball, & Kramer

- University System of Georgia via GALILEO Open Learning Materials

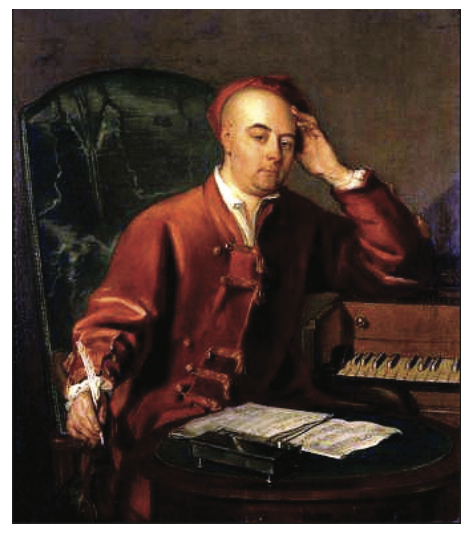

George Frideric Handel was one of the superstars of the late Baroque period He was born the same year as one of our other Baroque superstars, Johann Sebastian Bach, not more than 150 miles away in Halle, Germany. His father was an attorney and wanted his son to follow in his footsteps, but Handel decided that he wanted to be a musician instead. With the help of a local nobleman, he persuaded his father to agree. After learning the basics of composition, Handel journeyed to Italy to learn to write opera. Italy, after all, was the home of opera, and opera was the most popular musical entertainment of the day. After writing a few operas, he took a job in London, England, where Italian opera was very much the rage, eventually establishing his own opera company and producing scores of Italian operas, which were initially very well received by the English public. After a decade or so, however, Italian opera in England imploded. Several opera companies there each

competed for the public’s business. The divas who sang the main roles and whom the public bought their tickets to see demanded high salaries. In 1728, a librettist name John Gay and a composer named Johann Pepusch premiered a new sort of opera in London called ballad opera. It was sung entirely in English and its music was based on folk tunes known by most inhabitants of the British Isles. For the English public, the majority of whom had been attending Italian opera without understanding the language in which it was sung, English language opera was a big hit. Both Handel’s opera company and his competitors fought for financial stability, and Handel had to find other ways to make a profit. He hit on the idea of writing English oratorio.

Oratorio is sacred opera that is not staged. Like operas, they are relatively long works, often spanning over two hours when performed in entirety. Like op- era, oratorios are entirely sung to orchestral accompaniment. They feature recitatives, arias, and choruses, just like opera. Most oratorios also tell the story of an important character from the Christian Bible. But oratorios are not acted out. Historically-speaking, this is the reason that they exist. During the Baroque period at sacred times in the Christian church year such as Lent, stage entertainment was prohibited. The idea was that during Lent, individuals should be looking inward and preparing themselves for the death and resurrection of Christ, and attending plays and operas would distract from that. Nevertheless, individuals still wanted entertainment, hence, oratorios. These oratorios would be performed as concerts not in the church but because they were not acted out, they were perceived as not having a “detrimental” effect on the spiritual lives of those in the audience. The first oratorios were performed in Italy; then they spread elsewhere on the continent and to England.

Handel realized how powerful ballad opera, sung in English, had been for the general population and started writing oratorios but in the English language. He used the same music styles as he had in his operas, only including more choruses. In no time at all, his oratorios were being lauded as some of the most popular performances in London.

His most famous oratorio is entitled Messiah and was first performed in 1741. About the life of Christ, it was written for a benefit concert to be held in Dublin, Ireland. Atypically, his librettist, took the words for the oratorio straight from the King James Version of the Bible instead of putting the story into his own words.

Once in Ireland, Handel assembled solo singers as well as a chorus of musical am- ateurs to sing the many choruses he wrote for the oratorio. There it was popular, if not controversial. One of the soloists was a woman who was a famous actress. Some critics remarked that it was inappropriate for a woman who normally performed on the stage to be singing words from sacred scripture. Others objected to sacred scripture being sung in a concert instead of in church. Perhaps influenced by these opinions, Messiah was performed only a few times during the 1740s. Since the end of the eighteenth century, however, it has been performed more than al- most any other composition of classical music. While these issues may not seem controversial to us today, they remind us that people still disagree about how sa- cred texts should be used and about what sort music should be used to set them.

We’ve included three numbers from Handel’s Messiah as part of our discussion of this focus composition. We’ll first listen to a recitative entitled “Comfort Ye” that is directly followed by an aria entitled “Every Valley.” These two numbers are the second and third numbers in the oratorio. Then we’ll listen to the Hallelujah Chorus, the most famous number from the composition that falls at the end of the second of the three parts of the oratorio.

|

Listening Guide For audio, go to: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GDEi...ature=youtu.be Tenor Anthony Rolfe Johnson with The Monteverdi Choir and the English Ba- roque Soloists and John Eliot Gardiner, Conductor |

| Composer: George Frideric Handel |

| Composition: “Comfort Ye” and “Every Valley” from Messiah |

| Date: 1741 |

| Genre: accompanied recitative and aria from an oratorio |

| Form: accompanied recitative—through composed; aria—binary form AA’ |

| Nature of Text: English language libretto quoting the Bible |

|

Performing Forces: solo tenor and orchestra |

|

What we want you to remember about this composition:

|

|

Other things to listen for:

|

|

Accompanied Recitative: “Comfort Ye” |

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Text and Form |

| 0:00 |

Reduced orchestra playing pia- no repeated notes |

|

|

0:13 |

Mostly stepwise, conjunct sung melody; |

Vocalist & light orchestral ac- companiment: “Comfort Ye my people” |

|

0:27 |

Orchestra and vocalist alternate phrases until the recitative ends |

Vocalist and light orchestral accompaniment: Comfort ye |

| Aria: “Every Valley” |

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Text and Form |

| 2:22 | Repeated motives; starts loud, ends with an echo | Orchestra plays ritornello |

|

2:39 |

Soloist presents melodic phrase first heard in the ritornello and the orchestra echoes this phrase |

Tenor and orchestra: Every valley shall be exalted |

|

2:52 |

Long melisma on the word exalt- ed...repeats High note on mountain and low note on “low” |

Tenor and orchestra: Shall be exalted And every mountain and hill made low |

|

3:17 |

Repeated oscillation between two notes to represent crookedness; then one note is sustained on the word straight. |

Tenor and orchestra: The crooked straight |

|

3:23 |

Repeated oscillation between two notes to represent roughness; then one note is sustained on the word plain. |

Tenor and orchestra: And the rough places plain |

| 3:38 | Melismatic descending sequence on the word “Plain” | Continued |

| 3:53 |

Goes back to the beginning, but with even more ornamentation from the melismas |

Tenor and Orchestra: “Every valley shall be exalted” (Repeti- tion of text and music) |

| 5:10 | Repeats the music of the ritornello one final time | Orchestra: ritornello |

|

Listening Guide For audio, go to: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ptBZ...ature=youtu.be Performed by English Baroque Soloists and Monteverdi Choir, Conducted by John Eliot Gardiner |

| Composer: George Frideric Handel |

| Composition: “Hallelujah” from Messiah |

| Date: 1741 |

| Genre: chorus from an oratorio |

| Form: sectional; sections delineated by texture changes |

| Nature of Text: English language libretto quoting the Bible |

| Performing Forces: solo tenor and orchestra |

|

What we want you to remember about this composition:

|

|

Other things to listen for:

|

| Timing |

Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture |

Text and Form |

|

0:00 |

Orchestra: |

|

|

0:09 |

Chorus + orchestra: |

Hallejulah |

| 0:26 | Chorus + orchestra: Dramatic shift to monophonic with the voices and orchestra performing the same melodic line at the same time. |

For the Lord God omnipotent reigneth |

|

0:34 |

Chorus + orchestra: Homophonic texture, as before. |

Hallelujah |

| 0:38 | Chorus + orchestra: Homophonic texture, as before. |

For the Lord God omnipotent reigneth |

| 0:45 | Chorus + orchestra: Homophonic texture, as before. | Hallelujah |

| 0:49 |

Chorus + orchestra: |

For the Lord God omnipotent reigneth |

| 1:17 | Chorus + orchestra: Homophonic texture, as before. |

The Kingdom of this world is begun |

| 1:36 |

Chorus + orchestra: |

And he shall reign for ever and ever |

| 1:57 | Chorus + orchestra: Homophonic texture, as before. |

King of Kings |

| 2:01 | Chorus + orchestra: Homophonic texture, as before. |

Forever, and ever hallelujah hallelujah |

|

2:05 |

Chorus + orchestra: Each entrance is sequenced higher; the women sing the monophonic repeated melody motive Monophony alternating with homophony |

And Lord of Lords...Repeated alternation of the monophonic king of kings and lord of lords with homophonic for ever and ever |

| 2:36 | Chorus + orchestra: Homophonic texture |

King of kings and lord of lords |

| 2:40 | Chorus + orchestra: Polyphonic texture (with some imitation) | And he shall reign for ever and ever |

| 2:52 |

Chorus + orchestra: The alternation of monophonic and homophonic textures. |

King of kings and lord of lords alternating with “for ever and ever” |

| 3:01 | Chorus + orchestra: Mostly homophonic |

And he shall reign...Hallelujah |

Focus Composition:

Movements from Handel’s Water Music Suite

Although Handel is perhaps best known today for his operas and oratorios, he also wrote a lot instrumental music, from concertos like Vivaldi wrote to a kind of music called the suite. Suites were compositions having many contrasting movements. The idea was to provide diverse music

in one composition that might be interesting for playing and listening. They could be written for solo instruments such as the harpsichord or for orchestral forces, in which case we call them orchestral suites. They often began with movements called overtures and modeled after the overtures played before operas. Then they typically consisted of stylized dance movements. By stylized dance, we

mean a piece of music that sounds like a dance but that was not designed for dancing. In other words, a stylized dance uses the distinct characteristics of a dance and would be recognized as sounding like that dance but might be too long or too complicated to be danced to.

Dancing was very popular in the Baroque period, as it had been in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. We have several dancing text- books from the Baroque period that mapped out the choreography for each dance. Some of the most popular dances included the saraband, gigue, minuet, and bourée. The saraband was a slow dance in triple meter, whereas the gigue (or jig) was a very fast dance with triple subdivisions of the beats. The minuet was also in triple time but danced at a much more stately tempo. The bourrée, on the other hand, was danced at a much faster tempo, and always in duple meter.

When King George I asked Handel to compose music for an evening’s diver- sion, the suite was the genre to which Handel turned. This composition was for an event that started at 8pm on Wednesday the seventeenth of July, 1717. King George I and his noble guests would launch a barge ride up the Thames River to Chelsea. After disembarking and spending some time on shore, they re-boarded at 11pm and returned via the river to Whitehall Palace, from whence they came. A contem- porary newspaper remarked that the king and his guests occupied one barge while another held about fifty musicians and reported that the king liked the music so much that he asked it to be repeated three times.

The bourée, as noted above, is fast and in duple time. The minuet is in a triple. Many of the movements that were played for the occasion were written down and eventually published as three suites of music, each in a different key. You have two stylized dance movements from one of these suites here, a bourée and a minuet. We do not know with any certainty in what order these movements were played or even exact- ly who played them on that evening in 1717, but when the music was published in the late eighteenth century, it was set for two trumpets, two horns, two oboes, first violins, second violins, violas, and a basso continuo, which included a bas- soon, cello(s), and harpsichord.

The bourée, as noted above, is fast and in duple time. The minuet is in a triple meter and taken at a more moderate tempo. They use repeated strains or sections of melodies based on repeated motives. As written in the score, as well as interpreted today in the referenced recording, different sections of the orchestra—the strings, woodwinds, and sometimes brass instruments—each get a time to shine, providing diverse timbres and thus musical interest. Both are good examples of binary form.

|

Listening Guide For audio, go to: www.youtube.com/watch?v=Se54...ature=youtu.be The English Concert, on period instruments. Trevor Pinnock, conductor. [Bourée at 8:26] |

| Composer: George Frideric Handel |

| Composition: Bourée from Water Music |

| Date: 1717 |

| Genre: stylized dance movement from a suite |

| Form: Binary form, AABB, performed here three times; B is twice as long as A |

|

Performing Forces: Baroque orchestra: according to the musical score, 2 trumpets, 2 horns, 2 oboes, 1 bassoons, 1st violins, 2nd violins, violas, cello, and basso continuo (the cellos play the same music as the bassoon) |

|

What we want you to remember about this composition:

|

|

Other things to listen for:

|

| Timing |

Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture |

Text and Form |

|

8:26 |

Strings, basso continuo, trumpet Short phrase A of four measures, repeated |

A, repeated |

|

8:36 |

Same instruments play an answer phrase B of eight measures with descending motivic sequences |

B |

| 8:52 | Flute, oboe, bassoon, trumpets, strings Play the same A phrase as above |

A |

| 8:44 |

Repeated |

A |

| 9:01 | Same instruments play the B phrase | B |

| 9:09 | Repeated | B |

|

9:17 |

Strings, trumpets, flute, oboe bas- soon, and basso continuo play the A phrase. |

A, repeated |

|

9:26 |

Same instruments play the B phrase. | B |

| 9:34 | Repeated | B |

|

Listening Guide For audio, go to: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Se54...ature=youtu.be The English Concert, on period instruments. Trevor Pinnock, conductor. |

| Composer: George Frideric Handel |

| Composition: Minuet from Water Music |

| Date: 1717 |

| Genre: Stylized dance from a suite |

| Form: AA BB, to be performed three times according to the score |

|

Performing Forces: Baroque orchestral: according to the musical score, 2 trumpets, 2 horns, 2 oboes, 1 bassoons, 1st violins, 2nd violins, violas, cello, and basso continuo (the cellos play the same music as the bassoon) |

||

|

What we want you to remember about this composition:

|

||

|

Other things to listen for:

|

||

|

Timing |

Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture |

Text and Form |

|

9:49 |

Strings, trumpets: triple meter in a major key; |

A |

| 9:59 | Repeated | A |

|

10:11 |

Starts with repeated notes in just strings, oboes, and bassoon and ascends and then the trumpets and horns join: melody ascends and descends, mostly by step; trumpet becomes more prominent new phrases with a three-note motive that repeatedly ascends and then descends by step |

B |

| 10:33 |

As with B above |

B |

| 10:55 |

Flute, oboes, bassoons, horns, trumpets, basso continuo including cello play the opening strain |

A |

| 11:07 |

Flute, oboes, bassoons, horns, trumpets, basso continuo including cello play the opening strain |

A |

| 11:18 |

First just double reeds, then adding horns |

A |

| 11:39 |

Repeated |

B |

| 12:02 |

Full orchestra |

A |

| 12:13 |

Repeated |

A |

| 12:24 |

First strings and then the full orchestra |

B |

| 12:46 | First strings and then the full orchestra | B |