7.8: Northern Europe in the 15th century- Northern Renaissance

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 147798

Northern Europe: 15th century

The Renaissance north of the Alps.

1400 - 1500 (Renaissance)

Beginner’s guide: Northern Europe in the 15th century

Much changed in northern Europe in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

1400 - 1500

Some of the most important changes in northern Europe include the invention of the printing press, the formation of a merchant class of art patrons that purchased works in oil on panel, the Protestant Reformation and the translation of the Bible from the original languages into the vernacular or common languages such as German and French, and international trade in urban centers.

The Medieval and Renaissance Altarpiece

The altar and the sacrament of the Eucharist

Every architectural space has a gravitational center, one that may be spatial or symbolic or both; for the medieval church, the altar fulfilled that role. This essay will explore what transpired at the altar during this period as well as its decoration, which was intended to edify and illuminate the worshippers gathered in the church.

The Christian religion centers upon Jesus Christ, who is believed to be the incarnation of the son of God born to the Virgin Mary.

During his ministry, Christ performed miracles and attracted a large following, which ultimately led to his persecution and crucifixion by the Romans. Upon his death, he was resurrected, promising redemption for humankind at the end of time.

The mystery of Christ’s death and resurrection are symbolically recreated during the Mass (the central act of worship) with the celebration of the Eucharist — a reminder of Christ’s sacrifice where bread and wine wielded by the priest miraculously embodies the body and blood of Jesus Christ, the Christian Savior.

The altar came to symbolize the tomb of Christ. It became the stage for the sacrament of the Eucharist, and gradually over the course of the Early Christian period began to be ornamented by a cross, candles, a cloth (representing the shroud that covered the body of Christ), and eventually, an altarpiece (a work of art set above and behind an altar).

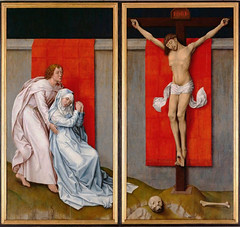

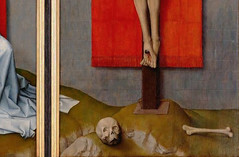

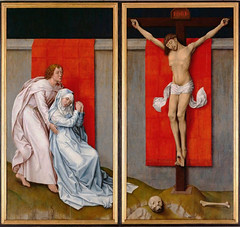

In Rogier van der Weyden’s Altarpiece of the Seven Sacraments, one sees Christ’s sacrifice and the contemporary celebration of the Mass joined. The Crucifixion of Christ is in the foreground of the central panel of the triptych with St. John the Evangelist and the Virgin Mary at the foot of the cross, while directly behind, a priest celebrates the Eucharist before a decorated altarpiece upon an altar.

Though altarpieces were not necessary for the Mass, they became a standard feature of altars throughout Europe from the thirteenth century, if not earlier. One of the factors that may have influenced the creation of altarpieces at that time was the shift from a more cube-shaped altar to a wider format, a change that invited the display of works of art upon the rectangular altar table.

Though the shape and medium of the altarpiece varied from country to country, the sensual experience of viewing it during the medieval period did not: chanting, the ringing of bells, burning candles, wafting incense, the mesmerizing sound of the incantation of the liturgy, and the sight of the colorful, carved story of Christ’s last days on earth and his resurrection would have stimulated all the senses of the worshipers. In a way, to see an altarpiece was to touch it—faith was experiential in that the boundaries between the five senses were not so rigorously drawn in the Middle Ages. For example, worshipers were expected to visually consume the Host (the bread symbolizing Christ’s body) during Mass, as full communion was reserved for Easter only.

Saints and relics

Since the fifth century, saints’ relics (fragments of venerated holy persons) were embedded in the altar, so it is not surprising that altarpieces were often dedicated to saints and the miracles they performed. Italy in particular favored portraits of saints flanked by scenes from their lives, as seen, for example, in the image of St. Francis of Assisi by Bonaventura Berlinghieri in the Church of San Francesco in Pescia.

The Virgin Mary and the Incarnation of Christ were also frequently portrayed, though the Passion of Christ (and his resurrection) most frequently provided the backdrop for the mystery of Transubstantiation celebrated on the altar. The image could be painted or sculpted out of wood, metal, stone, or marble; relief sculpture was typically painted in bright colors and often gilded.

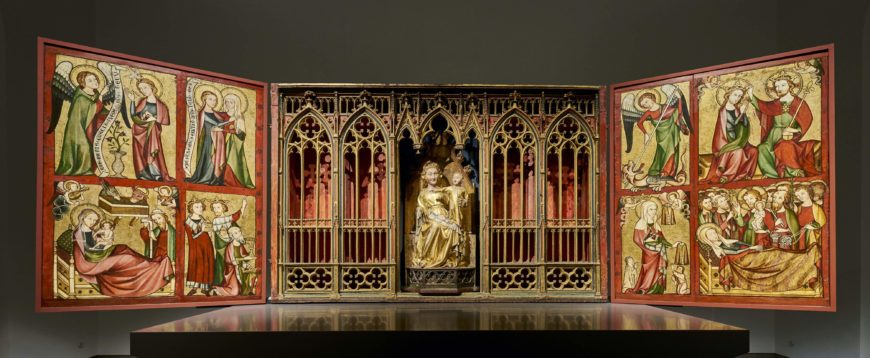

Germany, the Low Countries, and Scandinavia were most often associated with polyptychs (many-paneled works) that have several stages of closing and opening, in which a hierarchy of different media from painting to sculpture engaged the worshiper in a dance of concealment and revelation that culminated in a vision of the divine.

For example, the altarpiece from Altenberg contained a statue of the Virgin and Christ Child which was flanked by double-hinged wings that were opened in stages so that the first opening revealed painted panels of the Annunciation, Nativity, Death and Coronation of the Virgin (image above). The second opening disclosed the Visitation, Adoration of the Magi, and the patron saints of the Altenberg cloister, Michael and Elizabeth of Hungary. When the wings were fully closed, the Madonna and Child were hidden and painted scenes from the Passion were visible.

Variations

English parish churches had a predilection for rood screens, which were a type of carved barrier separating the nave (the main, central space of the church) from the chancel. Altarpieces carved out of alabaster became common in fourteenth-century England, featuring scenes from the life of Christ; these were often imported by other European countries.

The abbey of St.-Denis in France boasted a series of rectangular stone altarpieces that featured the lives of saints interwoven with the most important episodes of Christ’s life and death. For example, the life of St. Eustache unfolds to either side of the Crucifixion on one of the altarpieces, the latter of which participated in the liturgical activities of the church and often reflected the stained-glass subject matter of the individual chapels in which they were found.

Gothic beauty

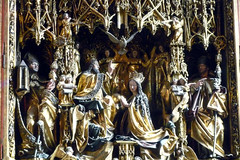

In the later medieval period in France (15th–16th centuries), elaborate polyptychs with spiky pinnacles and late Gothic tracery formed the backdrop for densely populated narratives of the Passion and resurrection of Christ. In the seven-paneled altarpiece from the church of St.-Martin in Ambierle, the painted outer wings represent the patrons with their respective patron saints and above, the Annunciation to the Virgin by the archangel Gabriel of the birth of Christ. On the outer sides of these wings, painted in grisaille are the donors’ coats of arms.

Turrets (towers) crowned by triangular gables and divided by vertical pinnacles with spiky crockets create the framework of the polychromed and gilded wood carving of the inner three panels that house the story of Christ’s torture and triumph over death against tracery patterns that mimic stained glass windows found in Gothic churches.

To the left, one finds the Betrayal of Christ, the Flagellation, and the Crowning with the Crown of Thorns — scenes that led up to the death of Christ. The Crucifixion occupies the elevated central portion of the altarpiece, and the Descent from the Cross, the Entombment, and Resurrection are represented on the right side of the altarpiece.

There is an immediacy to the treatment of the narrative that invites the worshiper’s immersion in the story: anecdotal detail abounds, the small scale and large number of the figures encourage the eye to consume and possess what it sees in a fashion similar to a child’s absorption before a dollhouse. The scenes on the altarpiece are made imminently accessible by the use of contemporary garb, highly detailed architectural settings, and exaggerated gestures and facial expressions.

One feels compelled to enter into the drama of the story in a visceral way—feeling the sorrow of the Virgin as she swoons at her son’s death. This palpable quality of empathy that propels the viewer into the Passion of Christ makes the historical past fall away: we experience the pathos of Christ’s death in the present moment.

According to medieval theories of vision, memory was a physical process based on embodied visions. According to one twelfth-century thinker, they imprinted themselves upon the eyes of the heart. The altarpiece guided the faithful to a state of mind conducive to prayer, promoted communication with the saints, and served as a mnemonic device for meditation, and could even assist in achieving communion with the divine.

The altar had evolved into a table that was alive with color, often with precious stones, with relics, the chalice (which held the wine) and paten (which held the Host) consecrated to the blood and body of Christ, and finally, a carved and/or painted retable: this was the spectacle of the holy.

As Jean-Claude Schmitt put it:

this was an ensemble of sacred objects, engaged in a dialectic movement of revealing and concealing that encouraged individual piety and collective adherence to the mystery of the ritual.J.-C. Schmitt , “Les reliques et les images,” in Les reliques: Objets, cultes, symbols

(Turnhout: 1999)

The story embodied on the altarpiece offered an object lesson in the human suffering experienced by Christ. The worshiper’s immersion in the death and resurrection of Christ was also an engagement with the tenets of Christianity, poignantly transcribed upon the sculpted, polychromed altarpieces.

Additional resources

Hans Belting, Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image before the Era of Art, trans. Edmond Jephcott (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994).

Paul Binski, “The 13th-Century English Altarpiece,” in Norwegian Medieval Altar Frontals and Related Materials. Institutum Romanum Norvegiae, Acta ad archaeologiam et atrium historiam pertinentia 11, pp. 47–57 (Rome: Bretschneider, 1995).

Shirley Neilsen Blum, Early Netherlandish Triptychs: A Study in Patronage (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1969).

Marco Ciatti, “The Typology, Meaning, and Use of Some Panel Paintings from the Duecento and Trecento,” in Italian Panel Painting of the Duecento and Trecento, ed. Victor M. Schmidt, 15–29. Studies in the History of Art 61. Center for the Advanced Study in the Visual Arts. Symposium Papers 38 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002).

Donald L. Ehresmann, “Some Observations on the Role of Liturgy in the Early Winged Altarpiece,” Art Bulletin 64/3 (1982), pp. 359–69.

Julian Gardner, “Altars, Altarpieces, and Art History: Legislation and Usage,” in Italian Altarpieces 1250–1500: Function and Design, ed. Eve Borsook and Fiorella Superbi Gioffredi, 5–39 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994).

Peter Humfrey and Martin Kemp, eds., The Altarpiece in the Renaissance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

Lynn F. Jacobs, “The Inverted ‘T’-Shape in Early Netherlandish Altarpieces: Studies in the Relation between Painting and Sculpture” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 54/1 (1991), pp. 33–65.

Lynn F. Jacobs, Early Netherlandish Carved Altarpieces, 1380–1550: Medieval Tastes and Mass Marketing (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Justin E.A. Kroesen and Victor M. Schmidt, eds., The Altar and its Environment, 1150–1400 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2009).

Barbara G. Lane, The Altar and the Altarpiece: Sacramental Themes in Early Netherlandish Painting (New York: Harper & Row, 1984).

Henning Laugerud, “To See with the Eyes of the Soul, Memory and Visual Culture in Medieval Europe,” in ARV, Nordic Yearbook of Folklore Studies 66 (Uppsala: Swedish Science Press, 2010), pp. 43–68.

Éric Palazzo, “Art and the Senses: Art and Liturgy in the Middle Ages,” in A Cultural History of the Senses in the Middle Ages, ed. Richard Newhauser, pp. 175–94 (London, New Delhi, Sidney: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014).

Donna L. Sadler, Touching the Passion—Seeing Late Medieval Altarpieces through the Eyes of Faith (Leiden: Brill, 2018).

Beth Williamson, “Altarpieces, Liturgy, and Devotion,” Speculum 79 (2004): 341–406.

Beth Williamson, “Sensory Experience in Medieval Devotion: Sound and Vision, Invisibility and Silence,” Speculum 88 1 (2013), pp. 1–43.

Kim Woods, “The Netherlandish Carved Altarpiece c. 1500: Type and Function,” in Humfrey and Kemp, The Altarpiece in the Renaissance, pp. 76–89.

Kim Woods, “Some Sixteenth-Century Antwerp Carved Wooden Altar-Pieces in England,” Burlington Magazine 141/1152 (1999), pp.144–55.

An introduction to the Northern Renaissance in the fifteenth century

What was the Renaissance and where did it happen?

The word Renaissance is generally defined as the rebirth of classical antiquity in Italy in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Seems simple enough, but the word “Renaissance” is actually fraught with complexity.

Scholars argue about exactly when the Renaissance happened, where it took place, how long it lasted, or if it even happened at all. Scholars also disagree about whether the Renaissance is a “rebirth” of classical antiquity (ancient Greece and Rome) or simply a continuation of classical traditions but with different emphases.

Traditional accounts of the Renaissance favor a narrative that places the birth of the Renaissance in Florence, Italy. In this narrative, Italian art and ideas migrate North from Italy (largely because of the travels of the great German artist Albrecht Dϋrer who studied, admired, and was inspired by Italy, and he carried his Italian experiences back to Germany).

The Renaissance in Northern Europe

However, so much changed in northern Europe in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries that the era deserves to be evaluated on its own terms. So we use the term “Northern Renaissance” to refer to the Renaissance that occurred in Europe north of the Alps.

Some of the most important changes in northern Europe include the:

- – invention of the printing press, c. 1450

- – advent of mechanically reproducible media such as woodcuts and engravings

- – formation of a merchant class of art patrons that purchased works in oil on panel

- – Protestant Reformation and the translation of the Bible from the original languages into the vernacular or common languages such as German and French

- – international trade in urban centers

The fifteenth century: van Eyck

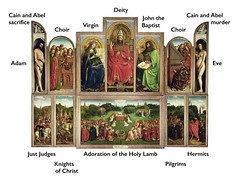

In the fifteenth century, northern artists such as Jan van Eyck introduced powerful and influential changes, such as the perfection of oil paint and almost impossible representation of minute detail, practices that clearly distinguish Northern art from Italian art as well as art from the preceding centuries. Jan and Hubert van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece, 1432 (Church of Saint Bavo, Ghent) exemplifies the grand scale and minute detail of Northern painting.

This public, religious picture has an opened and closed position. On the interior (above) we see such holy figures as the Virgin, Christ, saints and angels. It also showcases the largesse of the donors (left), depicted kneeling on the lowest corners of the exterior, who employed the van Eyck brothers to immortalize them in this very public work of art.

Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Double Portrait (1434) shows a well-to-do couple in a tasteful, bourgeois interior. The text in the back of the image identifies the date and Jan van Eyck as the artist. Art historians disagree about what is actually happening in the image, whether this is a betrothal or a marriage, or perhaps something else entirely. One of the most important aspects of this painting is the symbolic meanings of the objects, for instance that the dog may symbolize fidelity (“Fido”) or that the fruit on the windowsill may signify either wealth or temptation. This painting is a touchstone for the study of iconography, a method of interpreting works of art by deciphering symbolic meaning.

Though Jan van Eyck did not invent oil paint, he used the medium to greater effect than any other artist to date. Oil would become a predominant medium for painting for centuries, favored in art academies into the nineteenth century and beyond. The Arnolfinis counted as middle class because their wealth came from trade rather than inherited titles and land. The power of the merchant-class patrons of northern Europe cultivated a taste for art made for domestic display. Decorating one’s home is still a powerful motivation for art patrons. Museum visitors repeatedly comment, “well, I wouldn’t want it in my living room.”

Additional resources:

Jan van Eyck on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Introduction to Fifteenth-century Flanders

Material splendor

Jan van Eyck’s Rolin Madonna presents a series of objects and surfaces: a fur-lined damask robe, ceramic tiles, a golden crown, stone columns, warm flesh, flowers, translucent glass, and a reflective body of water. Even the air above the distant river seems palpable. The painting is a careful study of how light reacts to the varying textures. But the scene is an imagined one. Before a kneeling man the Virgin presents on her lap the Christ child, and an angel holds a crown above her. No eye contact is made. It is as if we are seeing what the man has in his mind’s eye as he prays from the book in front of him. While the sumptuousness of the surroundings belie the otherworldliness of the Mother and Child, at the same time they seem to augment rather than diminish their divinity. For Nicolas Rolin, the man in this image, it seems that attention to the magnificence and splendor of valuable arts and materials can provide a vision of the sacred, rather than distract from it.

Although Jan van Eyck’s painting is an exceptional artwork, it is typical of fifteenth-century Flemish art in the value it attributes to material splendor. The area of the southern Low Countries was one of the major contributors to what is often referred to as the Northern Renaissance—the efflorescence of artistic production that took place north of the Alps in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

Flemish art

“Flemish art” is a difficult term: medieval Flanders does not have the same borders as it does today. It is used by art historians loosely to refer to artistic production in Flemish speaking towns—particularly Bruges, Ghent, Brussels and Tournai. The term is also most often associated with painting. Painters like Jan van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden, and Hugo van der Goes were as internationally famous in their time as they are now, finding patrons not only in the Low Countries (today Netherlands, Belgium and northern Germany), but in Italy also, where their oil-paint technique had a considerable influence.

However, just as van Eyck was attentive to the range of crafted objects in the Rolin Madonna, we too should be observant of the many arts practiced in fifteenth-century Flanders. There were workshops across the major towns of Flanders for goldsmiths, ceramicists, cabinet-makers, manuscript illuminators, tapestry weavers, and sculptors in wood and stone.

More than paintings

The most expensive artworks were tapestries and goldwork and nobles would commission these as gifts for their allies and relatives. The prominence painting is given today is partly because our culture values painting as a “fine art” alongside sculpture and architecture, and thus one distinct from the “decorative” or “applied” arts of other media. It is important to understand that these distinctions did not exist in the fifteenth-century Low Countries. Therefore, when visiting collections in search of Netherlandish art, also take time to seek out the rare surviving goldwork, tapestries, and sculpture. Singular pieces include the Liège statuette (a reliquary with images of Charles the Bold and St George in the Cathedral of Liège), the Burgundian tapestries at Bern Historical Museum, and the tombs of Mary of Burgundy and Charles the Bold in the Church of our Lady in Bruges.

A major trading center

To understand why Flanders became the site of such intensive artistic production in the fifteenth century, it is useful to consider its place within the wider western European economy. Flanders was the most urbanized region of northern Europe in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Between c. 1000 and 1300, its town and ports grew in size and number as it became the major center for trade in northern Europe, acting as a nodal point for merchants from England, the Baltic, Italy, and France. For this reason, its cities, particularly Bruges and Ghent, became centers of artistic production.

Craftsmen of all types—including painters, tapestry manufacturers, manuscript illuminators, goldsmiths, and sculpture in wood and stone—could rely on the trade networks that brought raw materials to these cities. Painters and sculptors established their own workshops and joined guilds that regulated the quality of their products, the prices for which they could be sold, as well as license those allowed to practice these crafts. The towns themselves often acted as a patrons, often commissioning sculpture and coats-of-arms for their municipal buildings. Particularly wealthy citizens also acted as patrons for some of the most famous Flemish paintings: Hubert and Jan van Eyck’s famous Ghent Altarpiece, made in 1432 for Ghent’s cathedral of Saint Bavo, was financed by the Ghent merchant Jodocus Vijd; the Italian banker and Bruges resident Tommaso Portinari was the patron of van der Goes’s Portinari Altarpiece; whereas the guild of archers of Leuven commissioned van der Weyden’s Descent from the Cross.

The Flemish towns therefore functioned as a crucible for both the highly specialized workshop labor needed to produce high-quality paintings, goldwork, textiles, and sculptures, and for the wealthy patrons that the craftsmen relied on. The fifteenth-century efflorescence of art in Flanders also coincided with the demographic recovery after the shock of the Black plague in the mid-fourteenth century. In addition, the wars between France and England, which had slowed the Flemish economy, gradually subsided during this period. But these were not the only factors in the development of Flemish visual art. Another major source of patronage came from the Burgundian court.

Part of the Burgundian court

In 1384 the count of Flanders, Louis II, died, and he was succeeded by his son-in-law, Philip the Bold, the fourth son of King John II of France and the Duke of Burgundy. Flanders was from then ruled by a series of Burgundian dukes, and many craftsmen from the Flemish towns were enlisted by the Burgundian court where they would work for the duke and his courtiers. To return to where we began, Nicolas Rolin, the man depicted in Van Eyck’s Rolin Madonna and the patron of that painting, was a high-ranking Burgundian courtier. In addition to being a patron of van Eyck, he also commissioned van der Weyden to make a large altarpiece for the hospice he endowed in Beaune (where it can still be seen).

After the death of Duke Charles the Bold in 1477, the Burgundian lands were partitioned between France and the Holy Roman Empire, and many Netherlandish artists lost the court’s patronage as a result. Furthermore, the towns of Bruges and Brussels were losing their economic importance to Antwerp, and the painters there favored a quicker method of painting suited for widespread sale on that city’s international markets, rather than the slower, more layered and labored technique of their forebears. However, the influence of fifteenth-century Netherlandish painting would continue into the next century, particularly in the closely observed still life and portrait paintings by court artists such as Hans Holbein the Younger and Albrecht Dürer.

Additional resources:

Northern European Painting of the 15th-16th centuries from the National Gallery of Art

Burgundian Netherlands on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Jan van Eyck on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Early Netherlandish Painting on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Guy Delmarcel, Flemish Tapestry from the 15th to the 18th Century, trans. Alastair Weir (Tielt, 1999)

Craig Harbison, The Mirror of the Artist: Northern Renaissance Art in its Historical Context (New York, 1995)

Craig Harbison, Jan van Eyck: The Play of Realism (2nd ed.; London, 2012)

Susie Nash, Northern Renaissance Art (Oxford, 2008)

James Snyder, Northern Renaissance Art: Painting, Sculpture, the Graphic Arts from 1350 to 1575 (2nd ed.;New York, 2005)

Hugo Van der Velden, The Donor’s Image: Gerard Loyet and the votive portraits of Charles the Bold (Turnhout, 2000)

Introduction to Burgundy in the Fifteenth Century

“The unlimited arrogance of Burgundy! The whole history of that family, from the deeds of knightly bravado, in which the fast-rising fortunes of the first Philip take root, to the bitter jealousy of John the Fearless and the black lust for revenge in the years after his death, through the long summer of that other magnifico, Philip the Good, to the deranged stubbornness with which the ambitious Charles the Bold met his ruin – is this not a poem of heroic pride? Burgundy, as dark with power as with wine…greedy, rich Flanders. These are the same lands in which the splendour of painting, sculpture, and music flower, and where the most violent code of revenge ruled and the most brutal barbarism spread among the aristocracy.”

—Johan Huizinga, The Autumn of the Middle Ages, 1919 (1996 english ed.)

This remarkable passage from Johan Huizinga’s early twentieth-century classic The Autumn of the Middle Ages anticipated how the history of Burgundy has been written by many later historians: that is, as a series of successive dukes (Philip the Bold, John the Fearless, Philip the Good, and Charles the Bold).

The first of these, Philip the Bold, became one of the wealthiest individuals in western Europe after he inherited the county of Flanders from his father-in-law in 1384, adding to his lands in Burgundy. His successors expanded on these holdings to create a territorial power located between France and the Habsburg Empire.

From the beginning, the dukes of Burgundy aspired to rival kings in their magnificence and authority. Their wealth and access to Flemish craftsmen enabled the dukes to produce one of the most visually splendorous court cultures in western Europe, one that in turn influenced royal patronage and ceremony in Spain, France, England, and the Habsburg Empire.

Monastery as monument

The first major project undertaken by a Burgundian duke was the construction of a Carthusian monastery outside Dijon, the Charterhouse of Champmol (1383—c. 1410), eventually served as a mausoleum for Philip the Bold and many of his descendants. The monastery was destroyed during the French Revolution and the site is now a psychiatric hospital, but some monuments from it survive, including the tombs of Philip the Bold and John the Fearless.

Other monuments include the so-called Well of Moses, which sits above a well in the main cloister of the monastery, and which includes life-size statues of Old Testament prophets below a crucifixion scene (that does not survive). The base with the prophets can still be visited in its original place, as can the portal to the church of the Charterhouse, which still has life-size statues in deep relief of Philip and his wife Margaret praying to the Virgin and Child and supported by donor saints. The Charterhouse of Champmol was intended to secure Philip’s memory and prayers for his soul after he died, but it was also a political monument, serving to remind his family and peers of his wealth and power.

A turn towards Flanders

During the fifteenth century the main site of ducal patronage moved towards the Burgundian territories in the Low Countries. After the assassination of John the Fearless in the presence of the French king in 1419, the third duke, Philip the Good, shifted his attention away from the intrigues of Paris and France, focusing instead on consolidating and expanding his territories in the Netherlands. The most famous artworks made in the court of Philip the Good are the paintings of Jan van Eyck, who Philip retained in his services.

Unfortunately, although we know van Eyck made portraits of Philip and his wife, Isabella of Portugal, there is no surviving work known to be commisssioned by Philip. As the art historian Craig Harbison has suggested, van Eyck might have been most often enlisted by the duke to decorate the courtly environment, either by painting walls or even designing stages and centerpieces for courtly ceremonies such as weddings, funerals, and tournaments. One of the most spectacular types of ceremonies would have been “Joyous Entries”: civic processions in which the duke and his entourage were guided through and around a town lined with pageantry, plays, and tableaux vivants. These events marked a town’s acceptance of their new or current ruler.

Knights of the Golden Fleece

Philip the Good and Charles the Bold knew their titles (Dukes) were inferior to those of their neighbors (including the Holy Roman Emperor and the King of France), and they both sought crowns from the Holy Roman Emperor. Both also had ambitions to launch crusades against the Ottoman Empire. Even though these later two dukes never went on crusade, they often publicly fashioned themselves as defenders of Christendom. These two rulers therefore favored tapestries and manuscripts that depicted the lives and actions of chivalric heroes, particularly those of Alexander the Great (who conquered the east) and Saint George (a Christian warrior). In 1454, Philip the Good even hosted a grand banquet, the famous “Feast of the Pheasant.” This spectacle was intended to encourage the members of the chivalric order Philip founded, the Knights of the Golden Fleece, to vow to support a crusade. The tables were decorated with statues, and automata (moving statues), and accompanied by music. An elephant (most probably a mechanical one) with an actor dressed as a woman personifying the church was led before the guests, and the Knights had to make their oath before a live pheasant decorated with pearls and a gold necklace (perhaps like that worn by members of the Golden Fleece).

Splendor and ambition

Not everyone in Burgundy shared these chivalric values. The refusal of the Netherlandish towns to fully support and fund Charles’s wars played a major part in his downfall and death at the Battle of Nancy in 1477. This event marked the beginning of the end for the Burgundian state, but its art and ceremony would remain a strong influence on the Habsburg dynasty that subsequently took control over the Burgundian Netherlands. The towns that had provided the crafts, stages, hosts, and audience for the Burgundian courts would also continue to develop their own civic visual and ceremonial cultures. The remarkable splendor and influence of the short-lived Burgundian court stemmed from its feverish and often violent ambition as a wealthy but precarious power in western Europe.

Additional resources:

Burgundian Netherlands: Private Life, and Burgundian Netherlands: Court Life and Patronage from The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Art from the Court of Burgundy: The Patronage of Philip the Bold and John the Fearless 1364-1419, Dijon, 2004.

Karl der Kühne (1433-1477). Kunst, Krieg und Hofkultur, Susan Marti, Gabriele Keck, Till H. Borchert (eds.), Bern, 2008.

Wim Blockmans and Walter Prevenier, The Promised Lands: The Low Countries Under Burgundian Rule, 1369-1530, Elizabeth Fackelman and Edward Peters (trans.), Philadelphia, 1999 (This is the shortest and most easily assessable introduction to the period).

Wim Blockmans and Walter Prevenier, The Burgundian Netherlands, Cambridge, 1986.

Sherry C. M. Lindquist, Agency, Visuality and Society and the Charterhouse of Champmol, Aldershot and Burlington, 2008

Biblical Storytelling: Illustrating a Fifteenth-Century Netherlandish Altarpiece

by THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Video from The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Norfolk Triptych and how it was made

by MUSEUM BOIJMANS VAN BEUNINGEN

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): The Norfolk Triptych, c. 1415-20, oil on panel, 33.1 x 16.35 x 2.85 cm (Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam).

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Layer By Layer, reconstruction by art historian and painting restorer Charlotte Caspers. Produced by Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam. Video from ARTtube.

Burgundian and adjacent territories

Ruled by a succession of very wealthy Dukes, Burgundy (today parts of France, Germany, Luxembourg, Belgium and the Netherlands) produced some of the most important art of the 15th century.

1400 - 1500 (Northern Renaissance)

Fit for a duke: Broederlam’s Crucifixion Altarpiece

An altarpiece fit for a duke

The two beautiful paintings above, by Melchior Broederlam, were made for the exterior of an altarpiece. Inside was an elaborately carved wooden triptych (below).

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\)

The interior was sculpted by Jacques de Baerze (it was common to combine sculpture and painting in a single altarpiece — see this later example by Rogier van der Weyden). Together, the paintings (by Broederlam) and sculpture (by de Baerze) are known as the Crucifixion Altarpiece.

The Crucifixion Altarpiece of Champmol was commissioned by the Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Bold, for the monastery he founded known as the Chartreuse de Champmol (charterhouse/monastery of Champmol), outside of Dijon, France.[1] At the time, Dijon was the capital of the Duchy of Burgundy and the Duke — Philip the Bold — was one of the wealthiest individuals in western Europe.

The richly decorated monastery at Champmol was intended to be the final resting place for the duke and his family and so it housed the tomb carved for him.

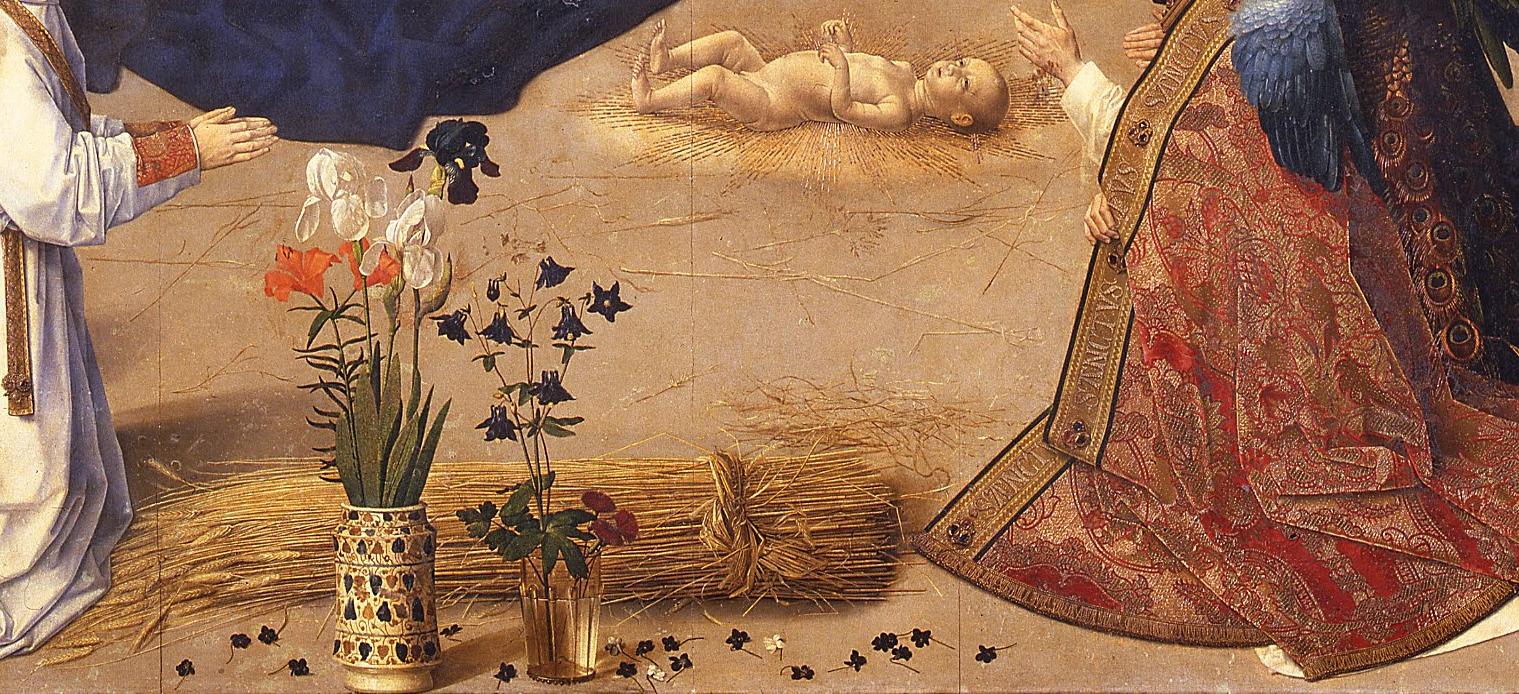

The Crucifixion Altarpiece illustrates the life of Christ from the time of his immaculate conception to that of his burial. (While Christ’s conception was immaculate — free from sin — the term Immaculate Conception is usually used to refer to Mary’s conception by her mother, Anne, rendering Mary the suitable mother for the child of God). The story begins on the exterior with Broederlam’s imagery which shows the early life of Christ: the Annunciation, the Visitation, the Presentation in the Temple, and the Flight into Egypt. The narrative continues when the altarpiece is open, beginning with the Adoration of the Magi, then the Crucifixion of Christ (the central and largest of the scenes), and the final representation of Christ’s Entombment.

International Gothic

Broederlam’s two painted panels are an exquisite example of the International Gothic style which developed in the courts of Europe in the 15th century. The International Gothic style often features rich colors, gold, and carefully observed naturalistic details placed within a somewhat illogical space. The figures and architecture of the International Gothic style are commonly given a delicacy and elegance that can be seen here.

The visual delight of Broederlam’s panels

It is safe to say that Broederlam’s two panels are visually complex. Not only did he delight in the International Gothic style of the period, but he also painted with an eye toward naturalism and capturing of minute detail.

Broederlam balanced the pictorial elements in each panel, arranging architecture, landscape, and figures so they are in visual harmony with one another. For example, in both panels, the architectural structures are placed to the left, while the landscape occupies the right side of the composition. As a result, when the panels are side by side, there is an alteration of architecture and landscape.

Similarly, in both panels, the landscape rises to the right with rocky, undulating hills, each surmounted by a walled town. Also in both panels, an angel fills the space in the panel’s rectangular projection. Tying all these elements together is Broederlam’s repeated use of red, blue, and pink, keeping the viewer’s eye moving from one scene to the next and creating continuity amongst the individual events.

Annunciation and Visitation

At the left side of the left panel, the Annunciation to the Virgin depicts the moment when the angel Gabriel announces to Mary that she will bear the son of God (Luke 1:26-38 and Matthew 1:18-22). The event takes place within an elaborate architectural space. To the right, Mary, dressed in her traditional blue robe, sits in her chamber before a lectern on which we see a book of hours.

However, Mary is not reading the book. instead, she turns her head to the right, as if caught by surprise, and raises her hand in acknowledgement of the angel Gabriel who has just alighted in the left foreground. Gabriel’s banderole pronounces Mary’s new role as mother of the Savior. The Holy Spirit enters Mary through the golden rays that issue from God the Father’s mouth in the upper left corner. Two elements emphasize that the conception of Christ was immaculate (without sin): the vase of white lilies in front of Gabriel is a traditional symbol of the Virgin’s purity as is the walled garden behind Gabriel, known as the hortus conclusus.

The next event, the Visitation, depicts the moment when the Virgin Mary, again dressed in blue, encounters Elizabeth, the mother of John the Baptist. According to tradition, both women were pregnant when they encountered each other. As John the Baptist recognized Christ as the Savior, he “leapt with joy” in his mother’s womb (Luke 1:42-45). The two women stand before a rocky landscape crowned by a fortified town. Small trees and bushes dot the landscape and a solitary bird flies through the sky, silhouetted against the gold leaf background.

Within this panel, color ties the two events together. Mary is seen twice in her traditional blue garment, the red of Elizabeth’s dress corresponds with that of Gabriel’s robe, and both relate to the red and blue that surround God the Father in the upper left corner.

The Presentation in the Temple and the Flight into Egypt

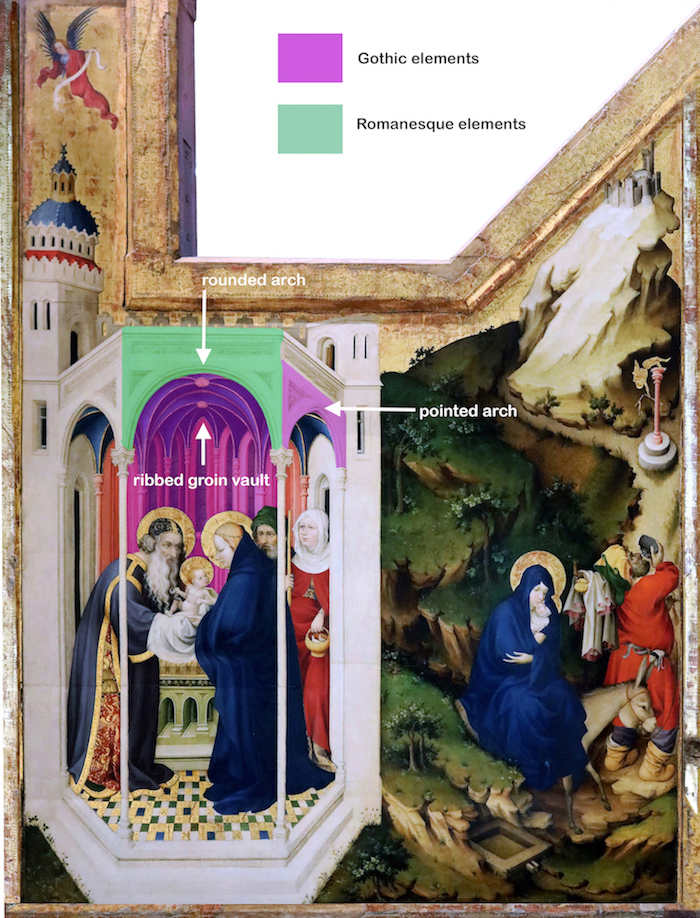

On the right-side panel, the Presentation in the Temple illustrates the moment when Christ is presented to the priest (Luke 2:22-40). The Virgin Mary presents the Christ Child by holding him above a golden altar inside an elegant temple that combines elements of Romanesque and Gothic architecture.

Here, the Romanesque rounded arches contrast with the ribbed groin vault and pointed arch windows, both of which are characteristic of Gothic architecture. Broederlam also used this combination in the Annunciation, where the pink Romanesque church is juxtaposed against the more Gothic structure of the open loggia where the Virgin Mary sits. This pairing of the two styles of architecture has been interpreted as representing the Old and New Testaments. [2] Like the inclusion of a book of hours in the Annunciation scene, the style of the architecture dates to the period of the painting (not to biblical times) — possibly a deliberate choice to make the narratives feel more relevant and relatable.

In both scenes, Broederlam used intuitive perspective, where the buildings recede at opposite angles away from the front of the picture plane and the floors tilt forward, rather than recede back into space. By using this method, Broederlam created relatively three-dimensional spaces for his figures to inhabit. [3]

The final event represented on the panels is the Flight into Egypt—a journey undertaken by the Holy Family to flee the murderous intentions of King Herod (Matthew 2:13-23). In this scene, the Virgin and Christ Child sit on the back of a donkey as they undertake their arduous journey. The Virgin’s blue mantle is wrapped around the young infant in a gesture of motherly protection.

Leading the way is Joseph, Mary’s husband, and as if to emphasize the difficulty of the journey, Joseph drinks heavily from a water bag. The rocky path on which they are about to embark leads up to a fortified city. Halfway up the path, a golden idol falls from a pink column, signaling the transition to the new Christian era brought about by the birth of Christ.

The eternal resting place of the duke

Filled with brilliant color, elegant figures, and charming detail, Melchior Broederlam’s panels for the Crucifixion Altarpiece are visual delights in the purest sense. The style of these painted panels matches that of the carved, gilded interior and together they created a stylistically unified narrative of the life of Christ. The devotional content and lavish representation are perfectly suited for the Duke and his eternal resting place in Dijon.

Notes

[1] Charles Minott, “The Meaning of the Baerze-Broederlam Altarpiece,” in A Tribute to Robert A. Koch. Studies in the Northern Renaissance (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994), p. 132.

[2] James Snyder, Northern Renaissance Art. Painting, Sculpture, the Graphic Arts from 1350 to 1575 (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc., 2005), p. 54; Minott, p. 138.

[3] Anne Hagopian van Buren, “Broederlam, Melchior.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 28, 2017. Comparison has long been made between Broederlam’s composition and that of the Italian artist Ambrogio Lorenzetti, who painted the same subject for the Cathedral in Siena in 1342.

Additional resources:

Original Corpus of Christ from the Crucifixion Altarpiece, removed during the French Revolution (Art Institute of Chicago)

Hagopian van Buren, Anne. “Broederlam, Melchior.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press.

Minott, Charles. “The Meaning of the Baerze-Broederlam Altarpiece.” In A Tribute to Robert A. Koch. Studies in the Northern Renaissance. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994, pp. 131-141.

Snyder, James. Northern Renaissance Art. Painting, Sculpture, the Graphic Arts from 1350 to 1575. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc., 2005.

Claus Sluter and Claus de Werve

Claus Sluter (with Claus de Werwe), The Well of Moses

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

This work is located on the grounds of the former Chartreuse de Champmol, a Carthusian monastery in Dijon, France, established by Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. The prophets depicted include: Moses, David, Jeremiah, Zachariah, Daniel, and Isaiah.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Claus Sluter (with Claus de Werve), Mourners

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{6}\): Claus Sluter (with Claus de Werve), Mourners, Tomb of Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, 1410 (Museum of Fine Arts, Dijon)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Herman, Paul, and Jean de Limbourg

Limbourg brothers, Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry

Some background: the Limbourg Brothers

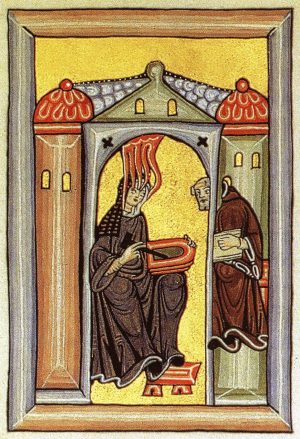

Known collectively as the Limbourg brothers, Paul, Jean and Herman de Limbourg were all highly skilled miniature painters active at the end of the 14th century and the beginning of 15th century. Together, they created some of the most beautiful illuminated books of the Late Gothic period.

The brothers hailed from the city of Nijmegen, currently part of the Netherlands. They came from an artistic family—their father was a wood sculptor, and their maternal uncle was an established painter who worked for Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. From the mid-1400s until the mid-1800s, the brothers’ legacy was lost in the mists of time until a dedicated bibliophile, Henri d’Orleans, duke of Amale, acquired one of their works, the Très Riches Heures, in 1856. This set off a flurry of study around the manuscript and its creators.

Though the exact birth years of the brothers are not known, it is believed that all three died in a wave of plague that hit Europe in 1416. All were likely under 30 years of age, which, though young to the contemporary mind, was a pretty standard life expectancy in the middle ages. Regardless, during their relatively brief lives, they were able to produce a number of complex and remarkable works.

The artistic lives of these brothers (at least Jean and Herman), began when they were sent at a young age to apprentice at a Parisian goldsmith. Apprenticeships—typical for craftsman in the middle ages—generally lasted around seven years. However, these were turbulent times and after only two years the boys were sent back home when a plague epidemic hit Paris in 1399. En route to return home to Nijmegen, they were captured in Brussels, which was experiencing conflict during this period. Jean and Herman were held in a prison for ransom. As their newly widowed mother did not have the funds to pay the ransom, the boys were held for approximately six months. Eventually Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy—patron of their uncle Jean—paid half the ransom. Painters and goldsmiths from their hometown contributed the other half. Some scholars believe that upon their release the young men traveled to Italy (though this is highly speculative).

A Moralized Bible

After their release, Philip the Bold commissioned the three brothers to create a miniature bible over a four-year period. Scholars assume this is the Bible Moralisée (Moralized Bible) which currently resides in the Bibliothèque National de France (Ms Fr166)—though this is a matter of some debate.

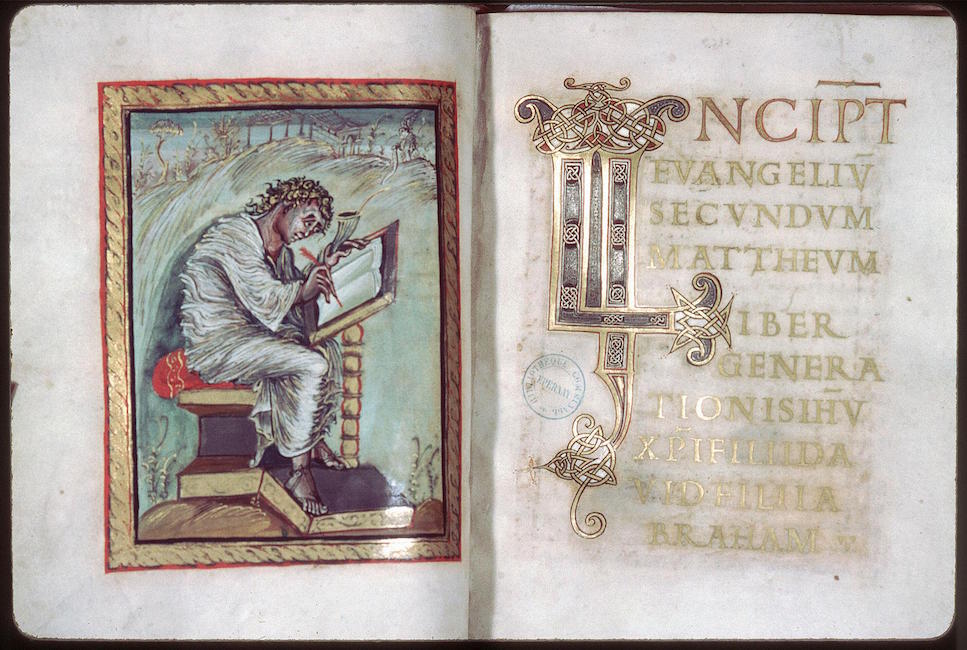

Bible moralisée, or moralized bibles, are a small group of illustrated bibles that were made in thirteenth-century France and Spain. These books are among the most expensive medieval manuscripts ever made because they contain an unusually large number of illustrations. They books were generally commissioned by members of royal families, as no one else would have been able to afford such luxury. Bible moralisée contain two texts: the biblical text and the commentary text, which is sometimes called a gloss. These commentary texts interpreted the biblical text for the thirteenth century reader. Commentary authors often created comparisons between people and events in the biblical world and people and events in the medieval world.

Their patron: the Duke of Berry

When Philip the Bold died in 1404, the future was uncertain for both the brothers and their uncle, but eventually Philip’s brother—Jean de France, duc de Berry (John, Duke of Berry)—took on the still teenaged boys. They would go on to create the Belles Heures de Jean de France, Duc de Berry, or the “Beautiful Hours of the Duke of Berry,” for him. The story of the Limbourg Brothers is integrally tied to the wealthy and powerful Duke of Berry—a major patron of the arts and avid collector, and the manuscripts they produced for him.

The Belles Heures

The Belles Heures is a Book of Hours— a very popular book to possess during the late medieval period. A Book of Hours is essentially a prayer book (with prayers and readings for set times throughout a day), and it they typically featured the “Hours of the Virgin” (a set of psalms with lessons and prayers), a calendar, a standard series of readings from the Gospels, the Office for the Dead, the Penitential Psalms, and hymns (or some variation thereof). They were miniature works of art made for private use, and generally contained a number of intricate illuminations painstakingly created on vellum (calfskin). A book of hours was for personal, devotional use—it was not an official liturgical volume. Typically, these books of hours were quite petite.

The Limbourg brothers finished work on the “Belles Heures” around 1409—this was to be their only complete work. The Duke of Berry then commissioned another devotional book in 1411 or 1412, which would become the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (The Very Rich Hours of the Duke of Berry)—probably the best-known example of Gothic illumination.

Though the two manuscripts (the Belles Heures and the Très Riches Heures) were created in fairly close succession, stylistic differences are apparent, and it seems clear that at least one of the brothers (likely Paul as he was the eldest and the master of the workshop), spent some time in Italy studying Renaissance masters such as Pietro Lorenzetti. Whatever the case, there is a change in style—particularly in the way landscapes are depicted and in the decorative borders. This, along with its fine, extant condition, is part of what makes the Très Riches Heures one of the finest examples of Gothic illumination and the International Gothic Style.

The Tres Riches Heures

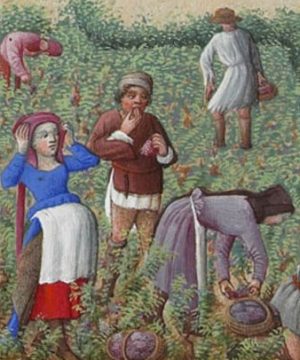

In the Très Riches Heures, there are a number of full-page images—including calendar pages. The calendar pages often show agricultural scenes where happy peasants till the fields and harvest. In the background are castles and landscapes that were specific holdings of the Duke of Berry. Likewise we also see the inside the palace. For example, in January (in full at the top of the page, and detail above) we see an image of the Duke himself, sitting at the head of the table while all around presents are exchanged. Likely, the Limbourgs themselves would have been part of this ritual exchange—the man in the mid-ground with the gray floppy cap may be a self-portrait of Paul. The table, resplendent in damask and laden with expensive goods, represents the wealth and taste of the Duke. A variety of heraldic motifs relating to the Duke can also be found, such as the gold fleur-de-lys (in the blue circles above the Duke for example). In the background we see tapestries with a scene of knights emerging from a castle ready to go into battle.

Meanwhile, the February page takes us outside into the frigid winter air. Wan light falls across a snow covered landscape where in the background we see a town blanketed in snow, along with a peasant and a donkey gamely taking the road towards it. In the middle ground we see another peasant diligently chopping wood, while another hurries towards shelter. In the foreground we see the farm as well peasants warming themselves in a small wooden house. he tunics of both the men are pulled so high, assumedly in an effort to warm their chilled legs, that their nether regions are exposed—something that might strike modern viewers as incongruous to a religious book. At least the lady of the house decorously only warms her ankles! However, nudity in medieval manuscripts, while not prolific, was also not unusual. In fact, there are several other examples that can be found in the “Très Riches Heures.”

Something else that might strike the modern viewer as curious is the incorporation of the zodiac into this book of hours. For every calendar page, the corresponding astrological sign is shown at the top of the page in a lunette or tympanum. This is in part because the stars were integrally tied to the agricultural calendar. Also, medieval medical practioners believed that people’s health issues were related to what constellation they were born under. Even the church calendar used the Zodiac to calculate feast days. For the month of May (below), we see the astrological signs of the bull and the twins, accompanying the chariot of the sun.

The International Gothic style

The International Gothic style emphasized decorative patterns. This is obvious on the clothing worn by the figures, but even natural forms—like trees—create decorative patterns. Gold leaf, always popular in manuscripts, was also used in abundance. Figures are elegant and elongated. These images are also highly detailed and show an abundant interest in accurately portraying plants and animals. Though the Très Riches Heures, is incomplete, it remains a shining example of the International Gothic style, along with such art works as The Annunciation by Simone Martini and Gentile Fabriano’s Adoration of the Magi.

Video \(\PageIndex{7}\)

Herman, Paul, and Jean de Limbourg, The Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry

by THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART

Video \(\PageIndex{8}\): Herman, Paul, and Jean de Limbourg, The Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry, 1405–1408/1409, tempera, gold, and ink on vellum, 9 3/8 x 13 7/16″ / 23.8 x 34.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art). Video from The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Campin and his workshop

Robert Campin, Christ and the Virgin

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{9}\): Robert Campin (also called the Master of Flémalle), Christ and the Virgin, c. 1430-35, oil and gold on panel, 11-1/4 x 17-15/16 inches (28.6 x 45.6 cm) (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Workshop of Robert Campin, Annunciation Triptych (Merode Altarpiece)

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{10}\): Workshop of Robert Campin, Annunciation Triptych (Merode Altarpiece), 1425-28, tempera and oil on panel (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Additional resources:

This painting at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

More on this painting from Dr. Allen Farber

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Jan van Eyck

Jan Van Eyck, The Ghent Altarpiece

Video \(\PageIndex{11}\): Jan van Eyck, The Ghent Altarpiece (closed), completed 1432, oil on wood, 11’ 5” x 7’ 6” (Saint Bavo Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium)

Video \(\PageIndex{12}\): Jan van Eyck, The Ghent Altarpiece (open), completed 1432, oil on wood, 11’ 5” x 7’ 6” (Saint Bavo Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium)

“All art constantly aspires to the condition of music”

– Walter Pater

A troubled past

When he wrote that statement, I doubt that Walter Pater had in mind the veritable rock opera that is the Ghent Altarpiece, now housed in the Cathedral of St. Bavo, Ghent (in present-day Belgium). From its singing, costumed, organ-pumping chorister angels to its gospel-choir legions of saints, soldiers, prophets and martyrs, to its central panel depicting the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb—is there any other fifteenth-century altarpiece that even comes close in spirit to the 1970s theatrical excesses of rock operas like Jesus Christ Superstar?

Since that time, the altarpiece has seldom failed to be in some process of constant condition monitoring (as T.S. Eliot would say “like a patient etherized upon a table”) or some kind of reconstruction or conservation—a kind of cultural-historical exercise in trying to perfect the past. The latest campaign of study, restoration and renewal has gone on since 2009, much of it carried out in front of the crowds at Saint Bavo’s Cathedral.

Video \(\PageIndex{13}\)

Astonishingly, given its many trials and tribulations, the altarpiece has weathered well. Only one of the original 12 panels (8 of which are part of the hinged shutter apparatus, and therefore painted on both sides), has been lost. In 1934 the panels depicting St. John the Baptist, and another depicting the Just Judges were stolen from the church. The John the Baptist panel was recovered. The Just Judges panel (on the lower left when the altarpiece is open—see image at the top of the page) was replaced with a modern copy during the 1945 restoration. The other panels have all survived, although there is some lingering disagreement about whether they are now reassembled in their original configuration, given the many times the altarpiece has been taken apart.

A pixilated present

The Getty Foundation in Los Angeles has funded the recent campaign to conserve the Ghent Altarpiece, an effort being led by Belgium’s Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage. A painstaking photographic enlargement is captured in 100 million pixels on the “Closer to Van Eyck” website. There, one can probe the impenetrably gorgeous enamel-like surface of van Eyck’s greatest masterpiece, and gaze astonished at his virtuosic accomplishments.

A moveable feast

Video \(\PageIndex{14}\)

The altarpiece itself is a visual “moveable feast,” made up of 12 panels that fold against themselves (see the video above). It is like frozen theatre, and when open, reveals a spiritual guidebook to divine revelation.

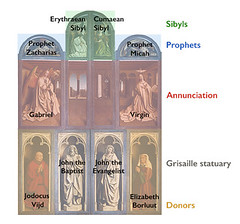

In its basic configuration, the rather austere, largely monochromatic outer panels (above)—which show the kneeling patrons and statues of prophets and glimpses into orderly rooms; are grounded in the material and sensible terrestrial world, in which Gabriel appears to Mary at the moment of the Annunciation. But when the altarpiece is opened, we travel, accompanied by prophets on foot and princes on horseback, saints and martyrs and more angels, to the brilliantly-colored heart of the scene depicting the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb (below). It is as if the makers of the Wizard of Oz derived their inspiration for a black-and-white Kansas and a technicolor Oz, from Ghent.

Byzantine influences

The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb (above) is presided over by the figure of God (the bearded Jesus with crown and scepter, below).* This figure can also be read as Christ Pantokrator (one of the many names for God in the Jewish tradition and, in the Bible, an appellation used only by John the Baptist to describe God), flanked by separate panels of John the Baptist to the right and the Virgin Mary to the left (below). The combination of these three figures reminds us of a Byzantine image type—the Deësis (from the Greek, “prayer”), which shows the intercession of the Virgin Mary and St. John the Baptist for the salvation of our souls, the heavenly interview at the moment of the Last Judgement (an example of a Byzantine Deësis, Byzantine art refers to art from the Byzantine or Eastern Roman empire).

In The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb (left detail), the sacrifice of the lamb, symbol of Christ’s slaughter for our salvation, is similarly Byzantine in origin.

The inner panels are painted in the bold and dynamic naturalistic style for which the artist Jan van Eyck is justifiably famous. In all of its positions, the Ghent Altarpiece is a vision of the visionary. It alludes not only to sight but to sound—musical angels accompanying the elaborate orchestration of the whole. Its appeal to the senses threatens to overwhelm the intellectual apprehension of its content.

The artists

According to an inscription, written on two silver strips mounted on the rear of the two donor panels, and only discovered in 1823, the altarpiece was painted by the brothers Jan and Hubert van Eyck:

The painter Hubert van Eyck, than whom none was greater, began this work. Jan [his brother], second in art, completed it at the request of Joos [Jodocus] Vijd on the sixth of May [1432]. He begs you by means of this verse to take care of what came into being.

Because Jan van Eyck is seen as the far more famous of the two brothers, the reference to Jan as “second in art” has raised a few eyebrows among art historians, eager to assign the lion’s share of the work to young Jan. My own undergraduate professor postulated that what the inscription means is that Hubert was responsible for the actual construction of the altarpiece, which was later largely painted by Jan—a not unusual sequence of events in a fifteenth-century workshop (building polyptych, or many-paneled, altarpieces required construction knowledge, and painting them required an entirely different expertise). Hubert died in 1426, and the altarpiece was finished in 1432, so Jan probably took over the contract Hubert signed with the patron of the work, Judocos Vijd (sometimes spelled “Vijdt”), which also would have made Jan literally “second in art.”

We know Jan to have been an exquisite painter of miniatures who worked for the Dukes of Burgundy, and there are many aspects of the work here consistent with the detailed work of a manuscript illuminator, but there are also some important differences, particularly in scale. The relatively large size of the panels pushed Jan to new heights of virtuosity as a master of light; directional light, saturation, the softest scale of illuminations in the gradation of shadow, the construction of space through light and shade, symphonies of reflection and refraction alive in a world of textured surfaces—literally, the light of the world. Here, for the first time on such a scale, is a picture of the completely natural world saturated by the light of God—the perfect intermingling of divine illumination with the created world—and all described in paint. Van Eyck creates a world within the painting as substantial and real as the world outside the painting. Say what you will about Brunelleschi and Masaccio and linear perspective in Florence, without the subtlety of oil paint, their works look like mathematical equations beside the painted world of the Ghent Altarpiece.

The patrons

Like most Renaissance patrons, Jodocus Vijd was a wealthy merchant who sought to expiate the sin of being too fond of money by spending some of it on creating a monument to God. An influential citizen of Ghent, Vijd commissioned the altarpiece for the Church dedicated to St. John the Baptist (now the Cathedral of St. Bavo) in his home city as a means of saving his soul while simultaneously celebrating his wealth. Vijd was warden of the Church of St. John and assistant Burgomeister of Ghent, and he had a rich aristocratic wife, so he had plenty of money to commission the van Eyck brothers. It is uncertain the extent to which he influenced the iconography of the overall work, but he obviously spared no expense.

The distinctive faces of Jodocus Vijd and Elizabeth Borluut (the husband and wife patrons) are each shown in three-quarter view (left and below). They kneel in the traditional donor positions, with their hands clasped in prayer, facing each other and gazing vaguely toward the central panels. Undoubtedly, contemporaries would have recognized them taking pride of place in such an important civic church, and although the immediacy of their presence would fade with time, their identities as the donors of the work remain intact.

The altarpiece, closed

It is best to start in the smallest and most constricted stage of the altarpiece in its closed position. The kneeling donors are depicted on the outer extremes, separated by simulated statues of two standing saints painted in grisaille (shades of grey)—St. John the Baptist and St. John the Evangelist (above).

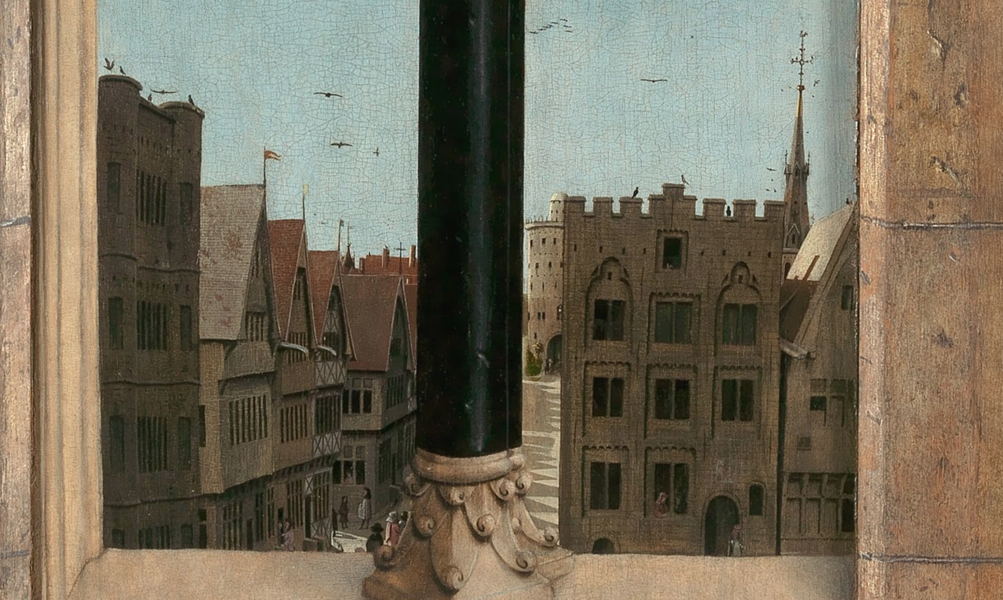

In the register above is a depiction of the Annunciation—this is the moment when the archangel Gabriel announces to Mary that she will be the mother of Christ (above). Figures of the angel and Mary are found on the outer edges of the panels. The Holy Spirit hovers over Mary. The two contiguous scenes between them are pure genre scenes (scenes of everyday life). Beside Gabriel, a window opens onto a view of buildings in Ghent (left), beside the Virgin, a recessed niche holds a silver tray, a small hanging silver pitcher and a linen towel neatly hanging from a rack (below). These items are consistent with iconography of the period that uses domestic objects as a means of expressing the purity of the Virgin. We are drawn most deeply into the center of the altarpiece (achieved without mathematically calculated perspective—you can tell because the floor appears to tilt upward), toward the mystery within.

At the top of the Gabriel panel, beneath a shallow rounded arch, is the Old Testament prophet Zacharias, father of John the Baptist; and above the Virgin, we see the Old Testament prophet Micah, who predicted the birth of the Messiah in Bethlehem. The two central panels in this upper register depict the Erythraean and Cumaean Sibyls (sibyls are female figures from ancient Greece and Rome who prophesied the future). These four figures are all messengers of the incarnation and sacrifice of Christ (Michelangelo painted these prophets and sibyls in the Sistine Chapel, and more).

The altarpiece, open

Opened, the altarpiece is divided into two horizontal registers. The Deësis (the Virgin Mary, Christ/God,* and St. John the Baptist) panels are flanked on either side by choirs of heavenly angels and, on the outermost panels at each side, Adam and Eve. God’s first human creatures are therefore the parenthetical figures of this upper register and the figures that necessitate the salvation scene below). Their literal marginalization—at the edges of the altarpiece—is indicative of their state of sin. Eve holds the forbidden fruit and covers her genitals. Opposite her, Adam assumes the classical pose of the so-called “modest Venus,” one arm across his chest, the other covering his genitals (a rather peculiar pose for a male figure to assume).

Adam and Eve’s sin in the garden of Eden (the Fall of Man) is, of course, the reason for all that occurs below in the panel known as the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb—the full salvation play, complete with sacrificial lamb, a symbolic representation of Christ (from Gospel of John: “The next day John saw Jesus coming toward him, and said, ‘Behold! The Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world!'”—John 1:29).

From the outer edges of the lower panels, crowds converge towards the altar in the center, presenting a unified field across the five panels, overcoming the Gothic division of the frame. From the left come figures known as the Just Judges and the Soldiers of Christ, on horseback, arrayed in glittering armor and armed with swords of Justice, followed by the Judges wearing opulent and various finery.

From the right come the saints and the prophets, chief among them the giant (and apocryphal) St. Christopher (below), the male saints suitably dressed in simple tunics and robes in sober earth tones. These crowds approach the central panel. Where are they all going? They’re going to witness the sacrifice of the Mystic Lamb.

The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb

The key panel of the altarpiece, the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb (detail above), depicts a large meadow, dotted with flowers, at the center of which are two key structures—in the foreground is a lovely octagonal stone fountain, with a tall central pedestal from which spring multiple cascades of water. In the background, on a direct axis with the fountain, is an altar with a lamb standing on it. The head of the strangely alert lamb is surrounded by a glowing nimbus (a halo, here depicted as golden rays). In the sky above, the dove of the Holy Spirit descends in its own pulsating nimbus of light from which radiate long, golden spires that touch the angels and the ground. Behind the altar, in the distance, are trees and one tall tower, punctuated by windows (left). Still further back on the blue horizon are distant mountains; the setting is a paradisaical landscape for the re-enactment of the sacrifice of Christ. What is the relationship between the altar, the sacrifice of the lamb, and the foreground fountain?

The Mystic Lamb is the Lamb of God—the sacrificial lamb—a symbol of Christ and Christ’s death. The lamb on the altar is equivalent to the crucifixion of Christ, made explicit by the juxtaposition of the lamb with the cross held by the angel. Other angels behind the altar hold the instruments of the Passion (the events surrounding Christ’s death): the column to which Christ was tied during the flagellation, the sponge on a stick used to touch his lips with vinegar (increasing his thirst), the nails and the lance that pierced his flesh. Angels in front of the altar swing censors containing incense (below). This is also a reference to the sacrament of the Eucharist, where the bread and wine, offered by the priest during Mass, become the body and blood of Christ.

The Lamb bleeds from a wound in his side, and this stream of blood flows directly into a chalice set on the altar cloth (the full inscription on the altar cloth reads, “Ecce Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis,” which translates, “Here is the Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world”). The flowing of the blood, visually linked to the spouts of water in the foreground fountain, is probably an allusion to Christ as the “living water” of God.

The fountain is therefore the Fountain of Life—a reference to the promise of eternal life made possible by Christ’s sacrifice. This reference to Christ as the “living water” occurs in the Gospel of John. In that story, Christ meets the Woman of Samaria at the well. When the woman questions Christ’s presence there, “Jesus answered and said unto her, If thou knewest the gift of God, and who it is that saith to thee, Give me to drink; thou wouldest have asked of him, and he would have given thee living water.” (John 4:14).

Inscribed on the fountain, in Latin (below), we see a verse from the Book of Revelation, “Then the angel showed me the river of the water of life, clear as crystal, proceeding from the throne of God and of the Lamb.” (Revelation, 22:1). In the symbolic context of the Lamb, the fountain is therefore the wellspring of eternal life and salvation.

Clustered around the fountain are yet more distinct processional groups worshiping the Lamb. These are commonly identified as patriarchs and prophets from the Old Testament and male and female saints and church figures. If you’re wondering what the Old Testament figures are doing in paradise, in the Byzantine tradition, Christ’s death is followed by his Harrowing of Hell (which takes place during the three days before his resurrection). In this episode (while “dead” to the world), Christ breaks open the doors of Hell. He frees and saves pagan writers (like Homer), prophets of the Old Testament (like Moses), and Adam and Eve—all of whose deaths preceded Christ’s birth and who could not otherwise have experienced eternal salvation through his resurrection.

Together, these scenes, which relate to the Gospel of John and the Book of Revelation, invite the viewer to share in the promise of salvation. These days, of course, we are invited to contemplate the altarpiece itself as a material survivor of time, war, reparation and restoration, and the painting has its own cult of dedicatees who worship it as an iconic work of art.

The sum of its parts (some thoughts on van Eyck’s sources and influences)

The iconography of the Ghent Altarpiece may be read in a myriad of ways, and it would be impossible to do justice to all of them here. But there is one more message that is, I think, important. The central panels of the open position may be read downward vertically; through the seated Christ/God* figure, to the descent of the dove of the Holy Spirit, to the Lamb on the altar. The symbolism of the Trinity (in Christian theology, God, the Holy Spirit and Christ are manifestations of one being) is important because it was a doctrine that was frequently challenged in the western Church. Again, the Gospel of John is often cited as most strongly defending and defining the divine nature of Jesus, and supporting the Trinitarian belief that the Holy Spirit shares the same being as Jesus and God. In the thirteenth century, a philosopher named Henry of Ghent, from Ghent of course, waded into the Trinitarian question through his work on the metaphysics of Being, and his work on the Metaphysics of the Trinity. It was not unusual for works of fifteenth-century art to engage with contemporary theological and philosophical debate.

The iconography of the Ghent Altarpiece suggests that the artists (or patron) drew on very particular sources, perhaps even Henry of Ghent, although this is merely speculation. Certainly, aspects of the iconography of the Ghent Altarpiece are peculiarly indebted to Byzantine art, which we know Jan van Eyck had studied. His genius was in the commingling of the timelessly iconic with the naturalistic play of light across the temporal textures of the world, transforming the material into the miraculous.

*The central figure of the top register of the open altarpiece has been identified as both Christ and God the Father. Some scholars has asserted that this ambiguity may have been purposeful.

Additional resources:

Getty Foundation Ghent Altarpiece initiative

A Smarthistory video on a Byzantine Deësis mosaic from Hagia Sophia

The Ghent Altarpiece from the Web Gallery of Art

The Ghent Altarpiece from The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Jan van Eyck, Portrait of a Man in a Red Turban (Self-Portrait?)

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{15}\): Jan van Eyck, Portrait of a Man in a Red Turban (Self-Portrait?), 1433, oil on oak panel, 26 x 19 cm (The National Gallery, London)

Jan van Eyck, The Madonna in the Church

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{16}\): Jan van Eyck, The Madonna in the Church, c. 1438, oil on oak, 31 x 14 cm (Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Jan Van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{17}\): Jan Van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait,1434, tempera and oil on oak panel, 82.2 x 60 cm (National Gallery, London)

Video \(\PageIndex{18}\)

Using infrared reflectography, Rachel Billinge explains aspects of the artist’s meticulous underdrawing for the work and some of the fascinating secrets it reveals.

Additional resources:

This painting at The National Gallery

The many questions surrounding Jan Van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait (from ARTstor)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

The question of pregnancy in Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait

But is she pregnant?

Jan van Eyck’s equally enigmatic and iconic Arnolfini Portrait often prompts art history newcomers and experts alike to ask: is the female figure pregnant? Questions about the presence of pregnancy in the portrait are so common that the London National Gallery’s website addresses the issue on the second line of the painting’s official explanatory text.

Is the woman in the Arnolfini Portrait pregnant? The short answer is no. The illusion is caused because the figure collects her extensive skirts and presses the excess fabric to her abdomen where it springs outwards and creates a domelike silhouette. Her hand position is regularly read by modern viewers as a universal acknowledgment of pregnancy, but in the Renaissance this gesture would have been understood instead as a sign of adherence to female decorum. Young Renaissance women were encouraged to keep their hands demurely clasped around their girdles when in public, as this was seen as polite and unobtrusive.

The issue of pregnancy in the Arnolfini Portrait is a complex one: the figure is not literally pregnant, because painting or sculpting pregnancy violated the period’s artistic customs—yet pregnancy is nevertheless present in the picture. Both pregnancy symbolism and expectation are at play within the painting.

Objects alluding to future pregnancy pepper the composition, from the ripened fruit arranged on the windowsill, to the wooden statuette of Saint Margaret, the patron saint of childbirth, who is shown overcoming the dragon of heresy on the bedframe. Though it’s impossible to sever the question concerning pregnancy from this painting, we can answer it by examining both Renaissance pregnancy and dress practices.

Renaissance pregnancy

The highly-gendered Renaissance world produced widely disparate male and female lived experiences. While a man generally married in his third or fourth decade, allowing him ample time to grow his business or estate, women became brides ideally between the ages of thirteen and seventeen. Women, therefore, were expected to and did spend the majority of their married lives with child.

Arnolfini’s wife is not pregnant in the picture, but period norms assumed she soon would be. Art historian Diane Wolfthal agrees that although the woman is not pictured pregnant, “the panel alludes to the proper goal of sexual relations through the wife’s protruding belly…her gesture…brings attention to her womb,”[1] and argues that the few period viewers who came into contact with the Arnolfini Portrait would have understood and recognized this signaling.

Although married Renaissance women spent the majority of their premenopausal lives with child, pregnancy itself was rarely represented. Artists working across a myriad of media shied away from depicting pregnancy, most likely because the condition was thought to be indecorous.

During the Renaissance, when a woman entered into her third trimester, she generally remained at home in a ritual called confinement. Further, depicting pregnancy admitted a direct link to human sexuality. Though procreative intercourse between heterosexual married couples was the only church-sanctioned form of sexuality in the Renaissance, to portray a married woman pregnant was generally seen as improper.

Rare exceptions exist, such as Raphael’s inscrutable Donna Gravida, or Portrait of an Unknown Lady attributed to Marcus Gheeraerts II, or the peasant woman toiling away in the fields in the September page of the Limbourg brothers’ Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry.

But even paintings depicting the Visitation—a moment in the Gospel of Luke when Mary and Elizabeth meet and both are pregnant (Mary with Christ, and Elizabeth with St. John the Baptist)—the two biblical heroines are rarely depicted as obviously gestational, though again, there are a few exceptions (for example, Rogier van der Weyden’s Visitation).

Another medium that offers a glimpse into Renaissance pregnancy and childbirth are birth trays, which were popular gifts for new mothers that would include jars and bowls containing soup and sweets.

Renaissance dress and gender norms

While the Arnolfini Portrait foregrounds many domestic objects, dress takes center stage. Both outfits in the portrait are ludicrously expensive and detailed, but the woman’s clothing outshines her husband’s. This excessive disparity in color and yardage is perfectly in line with Renaissance fashion and gender difference. Men’s outfits tended to be tailored from darker fabrics to signal the wearer’s sobriety and lack of vanity. In contrast, Renaissance women’s bodies in both images and reality were potent sites of material display. An exemplary upper-class wife was required to demonstrate her husband’s wealth (through his ability to keep her adorned in the latest fashion trends) as well as the couple’s potential fertility.