7.1: A beginner's guide to the Renaissance

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 147791

Expanding the Renaissance: a new Smarthistory initiative

If you google the word “Renaissance,” on the image tab, you’ll find yourself exclusively in Italy. Smarthistory would like to do something about that.

The Expanding Renaissance Initiative (ERI), is a new Andrew W. Mellon-funded project from Smarthistory to expand the boundaries of art history in the classroom—in this case specifically the early modern period. Our plan is to work towards art histories that do not present European art as superior and help to weaken the binary western/non-western paradigm. The ERI is aligned with recent scholarship on what has been called “the global renaissance,” and while we embrace the term “global,” the ERI aims to do more than simply globalize, but to highlight overlooked subjects, materials, artists, groups, and locales.

Disrupting the narrative

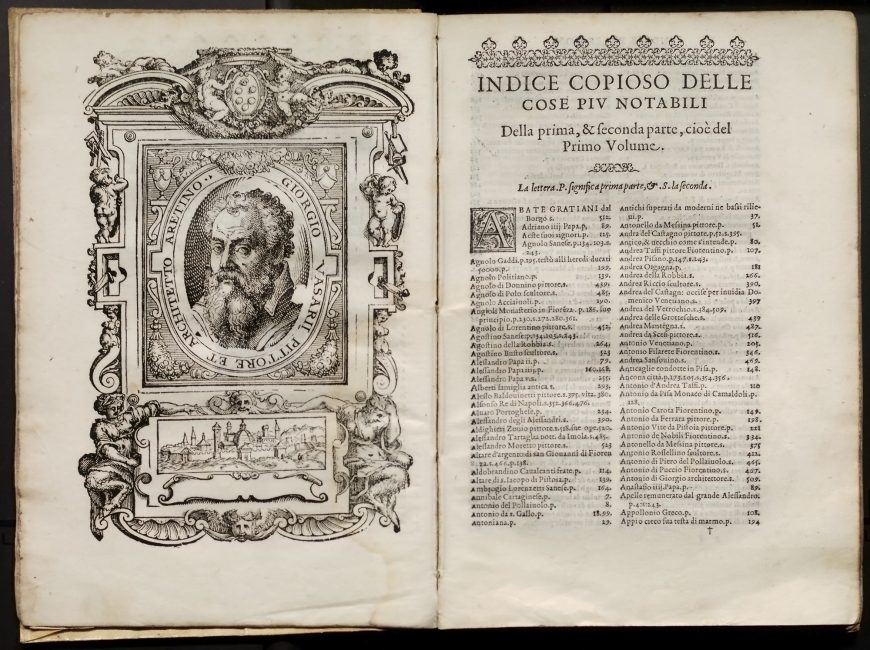

The most common narrative of the renaissance in art history focuses mainly on three periods of Florentine art in Italy as presented by Giorgio Vasari, who wrote the Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (first published in 1550). Vasari lived in Florence and so naturally celebrated Florentine artists as the best artists of that time. The problem is that many of the artists he praised are the very same artists that continue to receive the most attention in art history today (for example, Giotto, Masaccio, Michelangelo, Raphael). We too often neglect other artists, places, stories, and trends that can reveal a more complex and nuanced era.

While one of our goals is to decenter Italy as the area with the most important artists and art, we are not saying that there isn’t important and remarkable art from the Italian Peninsula that speaks to a relationship to the broader world. The point here is simply to note that even as we attempt to shift conversations in the classroom about the renaissance to account for greater cultural pluralism and interactions, it seems important to be mindful of, and examine, other areas as well.

The canon of renaissance art is slow to change. As of 2019, there exists no single textbook that addresses all of European renaissance art. Curiously, the Iberian peninsula (Spain and Portugal) and Ibero-American world remain entirely absent from any current textbook centered on the renaissance era. Even textbooks aimed at “The General Survey” include either nothing or very little about the Iberian Peninsula in chapters on the renaissance—ironically, El Greco (the Greek), has served to represent all of Spain.

The ERI foregrounds an expanded renaissance world, examining issues of global trade, cultural entanglements, colonization, itinerancy, empire, and gender and racial dynamics between roughly 1330 and 1650, in part to recognize the visual cultures and peoples of Africa, Asia, and the Americas as vital contributors (both willing and unwilling) to renaissance art and culture.

Women artists, indigenous artists, artwork made of understudied materials such as cochineal, carved gemstones, ceramics, painted alabaster, textiles, featherworks, ceramics, and sculpture made of terracotta, wood, and corn-pith — all speak to the vibrancy and challenges of this broader renaissance. Rather than focusing primarily on only “high art,” new content will highlight “key players in this new, globally connected practice of art history.”[1] The majority of such works are non-canonical, often forms that belong to large, influential genres and so are critically important to our understanding of the global renaissance. These works reveal fascinating stories about the renaissance world that would otherwise be lost to us.

The global renaissance?

Since the 2002 publication of Jerry Brotton’s The Renaissance Bazaar spurred greater interest in “The Global Renaissance,” there have been scholarly disputes about the usefulness of the idea of a global renaissance, and the best ways to approach it. Scholars have argued the extent to which cross-cultural contact occurred and the extent to which it transformed people’s lives and artistic production. However, even as interest in the global renaissance has grown, publications and exhibitions have, for the most part, remained Italo-centric, favoring especially Venice’s relationship with “the East.”

Recently, art historian Lia Markey has found that the global renaissance has not “significantly affect[ed] or alter[ed] teaching, the conception of the canon, or the permanent museum display.”[2] Still, many scholars continue to push the limits of the renaissance to “decenter the insularity of the Vasarian Renaissance,” as a way to challenge traditional narratives, ask new questions, and confront entrenched biases about renaissance art, and the field of art history more broadly.

A number of questions need to be asked: must all renaissance art history trumpet the achievements of famed artists such as Masaccio, Donatello, Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael, and Titian; or the Northern artists van Eyck, Dürer, Holbein, etc.? Can scholars allow themselves the freedom to center other narratives that reveal important facets of this period without always celebrating European male artistic genius? In what ways can a globalized renaissance art history directly confront ongoing issues of bias, discrimination, or racism in the field of art history? In the words of Claire Farago, “the geographical, cultural, chronological, and conceptual boundaries of the Renaissance as it is usually defined need to be redrawn” [3]. And not just in scholarship, museums, or renaissance art courses, but in general survey classes and beyond the borders of the Academy as well.

Visual entanglements

In 1604, the poet Bernardo de Balbuena wrote about Mexico City that “In thee Spain and China meet, Italy is linked with Japan, and now, finally, a world united in order and agreement.”[4] He wrote that Mexico City, capital of the viceroyalty of New Spain, had become a cosmopolitan linchpin between Asia and Europe, prospering as a result of a global trade system. Recent museum exhibitions (Made in the Americas: The New World Discovers Asia (MFA, Boston), Contested Visions in the Spanish Colonial World (LACMA) and Painted in Mexico, 1700–90: Pinxit Mexici (LACMA, The Met)) have focused on this transcultural exchange, offering visually captivating objects that attest to the impact of cultural interchange.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Folding Screen with the Siege of Belgrade (front) and Hunting Scene (reverse), c. 1697-1701, Mexico, oil on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl, 229.9 x 275.8 cm (Brooklyn Museum)

Clearly, global trade had made Mexico City a cosmopolitan center, but at what cost? Many publications and exhibitions use the words “exchange” and “cross-cultural exchange,” in a celebratory sense that seeks to unseat the idea that global travel and communication belong only to the 20th and 21st centuries, but can these terms adequately encapsulate the impact on the many peoples and cultures then coming into contact? Exchanges were not necessarily mutually beneficial, many were forced and fraught with violence. How then do we treat objects that result from violence? How do we discuss and categorize them? Should we use the stylistic categories we use for European art such as the renaissance, even if it marginalizes work that often exists in-between such categories? How do we not merely westernize world art history? We believe that the ERI has the potential to address some of these questions, to ignite conversations, and offer a model for how we can shift problematic, yet deeply ingrained classroom narratives.

Our aim is to reframe the renaissance to help students to discover that there is more that is important than Michelangelo’s David and Leonardo’s Mona Lisa. We hope to prompt further reflection on Sanjay Subrahmanyan’s suggestion that it is “good to think globally in order to redefine the possible objects of historical study.”[5] We also hope to prompt consideration of what is at stake in such a reframing, and what it means to decolonize renaissance art history, addressing the issue of not only content coverage, but also who gets to stand “behind the podium” to advance our knowledge of what is or isn’t renaissance art (this issue has been raised by Dr. Ananda Cohen-Aponte (@drnandico) on Twitter, in a discussion of #pocarthistory).

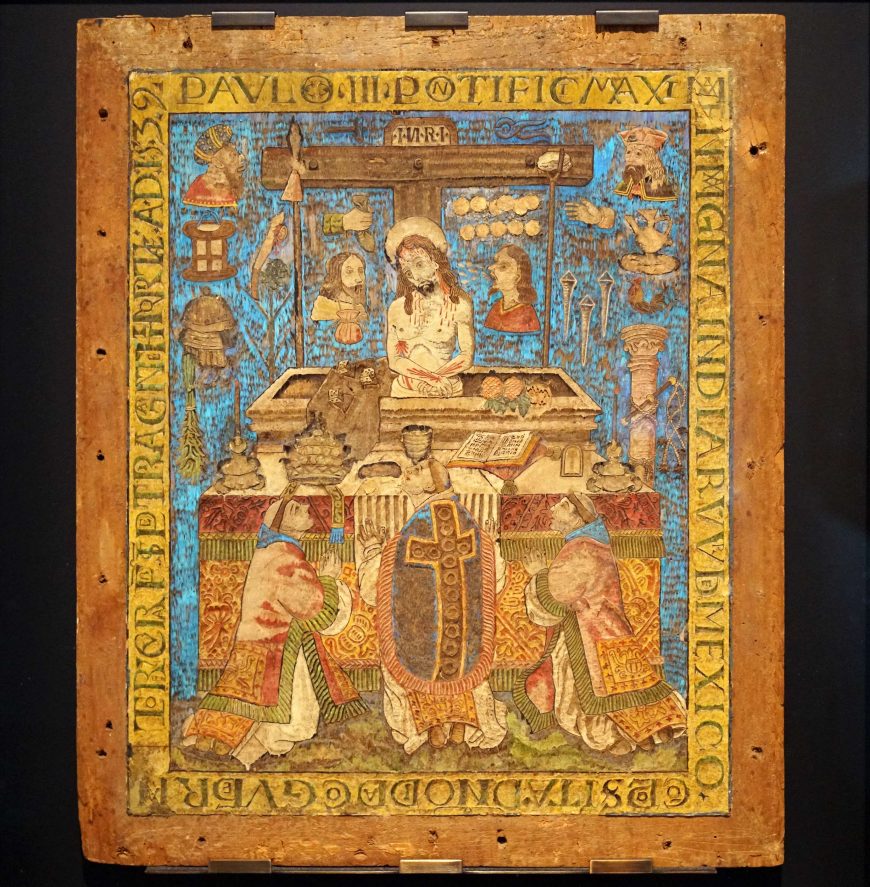

Many of the objects we intend to focus on speak to the mobility of things, people, and ideas in the early modern period, while also demonstrating the visual entanglements occurring as a result of globalization, colonization, and more. Networks of trade-connected ports, and markets functioned as nodes where objects were gathered, stored, and dispersed. Much of this globalization was the result of European colonization. And so armies were often followed by Christian missionaries who brought with them objects that played an important role in the development of transcultural art forms.

There were, of course, also countless artists who worked in these newly colonized regions, though their names often remain unknown to us. These artists drew on their own artistic traditions and cultural ideas while producing art and architecture. Some objects have visible artistic entanglements, while others do not. It is important that we address how colonized peoples borrowed, adapted, and rejected European forms, subject matter, and ideas (often forced on them), and what these choices might mean for our understanding of renaissance art. The black-and-white murals at the convento of San Agustín, Acolman, Mexico (c. 1560–90), painted by currently unknown indigenous artists, demonstrate a visual entanglement of artistic traditions from Central Mexico, Flanders, Italy, and Spain. They speak to the flexibility and the mobility of forms as they infiltrated colonized regions around the world. The murals of Acolman complicate the narrow definition of renaissance art we have clung to for too long.

The words we use

Intercultural objects like the murals at Acolman encourage us to critique commonly used terminology. We frequently hear phrases and terms like “Old World” and “New World” to describe Europe and the Americas, or the “Age of Discovery” or “Age of Exploration” to describe the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. But who do these terms privilege? To say “the New World” privileges the perspective of Europeans—after all, the Americas were only “new” to them. “Old World” suggests a place more ancient, with more history, and it ignores the complex, unique, and varied histories of many indigenous peoples across the Americas, as if they only really matter once Europe arrives to make them “new.” Similarly, it may have been an era of discovery for Europeans, but it was often a period of trauma for the many peoples around the globe who were “discovered.” The essays or videos created for the ERI speak to these issues and offer different objects for study, such as a Nahua featherwork or a Philippine ivory sculpture, as well as different perspectives about the renaissance more generally.

What’s coming with the ERI

This initiative will unfold over several years and will include essays about cabinets of curiosities and collecting practices of the Medici family, Theodore de Bry’s early engravings of the Americas, portraits of the female author Christine de Pizan, and the relationship between Spanish and Flemish painters in the fifteenth century.

We will also offer materials that reframe canonical artworks, examining them from different vantage points. For example, we are planning an essay that examines Hans Holbein’s The Ambassadors, specifically considering what the painting tells us about the globalized world at the time of its creation. Another essay will examine Gentile da Fabriano’s Adoration of the Magi through a similar lens, investigating what the psuedo-Arabic, painted silks and brocades, lapis lazuli, turbaned figures, and non-European animals tell us about this era.

An art history survey class could foreground how the period between 1400 and 1650 “was intensely, often violently, cross-cultural.”[6] Using materials largely drawn from Smarthistory, students could engage with and contextualize Netherlandish painter Hugo van der Goes’s Portinari Altarpiece and Florentine artists responses to it, Dürer’s Rhinoceros woodcut, a Medici blue-and-white porcelain, a Mexican featherwork and convento mural program, Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala’s 1200-page illustrated letter to the Spanish king, a Benin brass plaque of an oba, or a Sapi ivory salt-cellar sold to the Portuguese. Teachers will find materials that help introduce these materials into existing curriculum. Our hope is that the ERI will energize discussions of what renaissance art is, making it more relevant to our twenty-first century students.

2. Lia Markey, “Global Renaissance Art: Classroom, Academy, Museum, Canon,” in The Globalization of Renaissance Art: A Critical Review, edited by Daniel Savoy (Leiden: Koninklijke Brill), p. 260.

3. Claire Farago, “The Concept of the Renaissance Today: What is at Stake?” in Renaissance Theory, edited by James Elkins, Robert Williams (New York: Routledge, 2008), p. 71.

4. Bernardo de Balbuena: La grandeza mexicana y compendio apologético en alabanza de la poesía (Mexico City: Porrúa, 1975).

6. Dana Leibsohn, “Introduction: Geographies of Sight,” in Seeing Across Cultures in the Early Modern World, ed. Dana Leibsohn and Jeanette Favrot Peterson (London: Routledge, 2012), p. 2.

Additional resources:

Check out the expanded renaissance world short course on Smarthistory

Jerry Brotton, The Renaissance Bazaar (Oxford University Press, 2002)

Jeanette Peterson, “Renaissance: A Kaleidoscopic View from the Spanish Americas,” in Renaissance Theory, ed. James Elkins and Robert Williams (New York & London: Routledge, 2008)

Ananda Cohen-Aponte, “Decolonizing the Global Renaissance: A View from the Andes,” in The Globalization of Renaissance Art: A Critical Review, ed. Daniel Savoy (Leiden: Brill, 2017)

Dana Leibsohn, “Introduction: Geographies of Sight,” in Seeing Across Cultures in the Early Modern World, ed. Dana Leibsohn and Jeanette Favrot Peterson (London: Routledge, 2012)

The Medieval and Renaissance Altarpiece

by DR. DONNA L. SADLER

The altar and the sacrament of the Eucharist

Every architectural space has a gravitational center, one that may be spatial or symbolic or both; for the medieval church, the altar fulfilled that role. This essay will explore what transpired at the altar during this period as well as its decoration, which was intended to edify and illuminate the worshippers gathered in the church.

The Christian religion centers upon Jesus Christ, who is believed to be the incarnation of the son of God born to the Virgin Mary.

During his ministry, Christ performed miracles and attracted a large following, which ultimately led to his persecution and crucifixion by the Romans. Upon his death, he was resurrected, promising redemption for humankind at the end of time.

The mystery of Christ’s death and resurrection are symbolically recreated during the Mass (the central act of worship) with the celebration of the Eucharist — a reminder of Christ’s sacrifice where bread and wine wielded by the priest miraculously embodies the body and blood of Jesus Christ, the Christian Savior.

The altar came to symbolize the tomb of Christ. It became the stage for the sacrament of the Eucharist, and gradually over the course of the Early Christian period began to be ornamented by a cross, candles, a cloth (representing the shroud that covered the body of Christ), and eventually, an altarpiece (a work of art set above and behind an altar).

In Rogier van der Weyden’s Altarpiece of the Seven Sacraments, one sees Christ’s sacrifice and the contemporary celebration of the Mass joined. The Crucifixion of Christ is in the foreground of the central panel of the triptych with St. John the Evangelist and the Virgin Mary at the foot of the cross, while directly behind, a priest celebrates the Eucharist before a decorated altarpiece upon an altar.

Though altarpieces were not necessary for the Mass, they became a standard feature of altars throughout Europe from the thirteenth century, if not earlier. One of the factors that may have influenced the creation of altarpieces at that time was the shift from a more cube-shaped altar to a wider format, a change that invited the display of works of art upon the rectangular altar table.

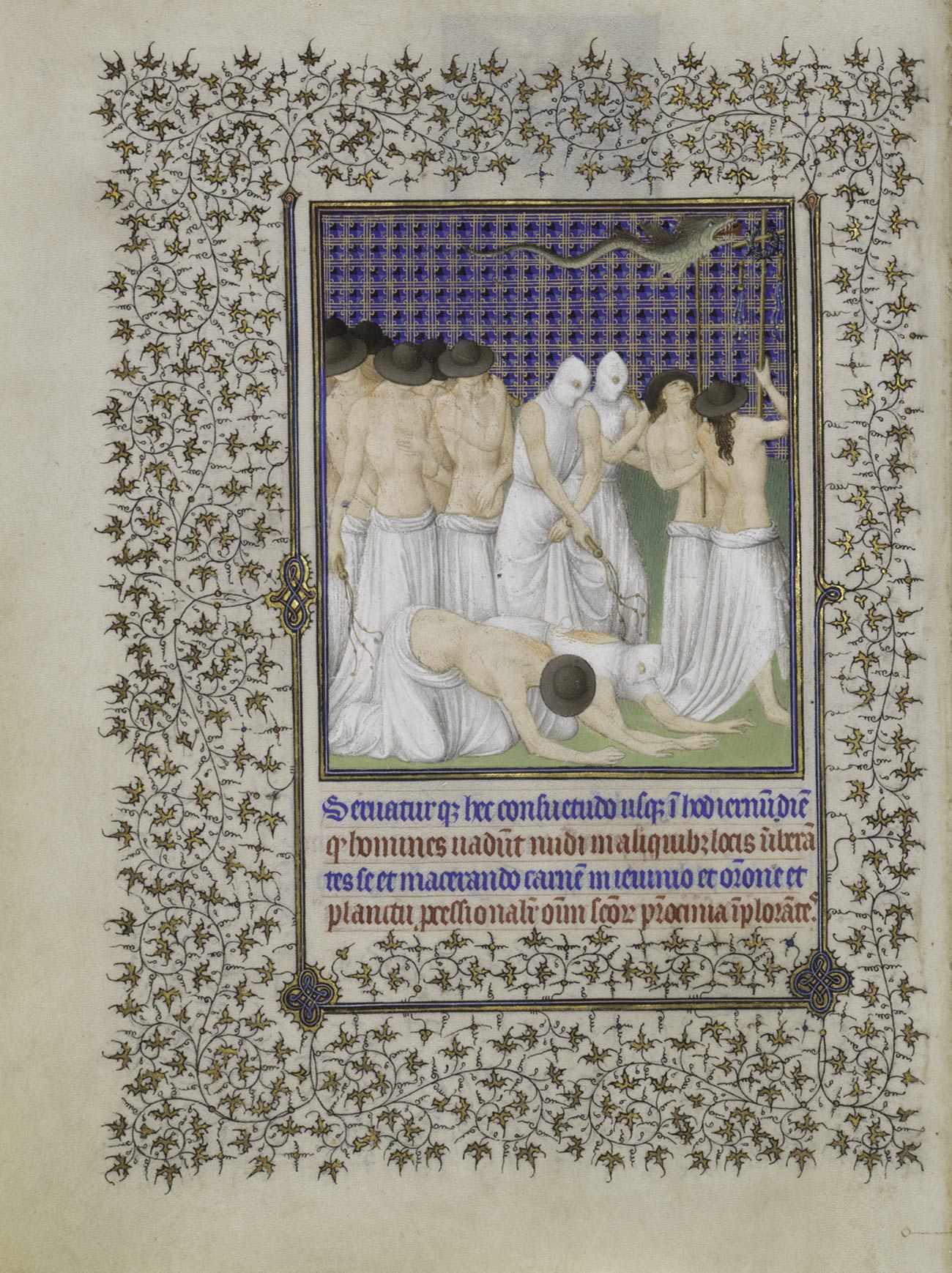

Though the shape and medium of the altarpiece varied from country to country, the sensual experience of viewing it during the medieval period did not: chanting, the ringing of bells, burning candles, wafting incense, the mesmerizing sound of the incantation of the liturgy, and the sight of the colorful, carved story of Christ’s last days on earth and his resurrection would have stimulated all the senses of the worshipers. In a way, to see an altarpiece was to touch it—faith was experiential in that the boundaries between the five senses were not so rigorously drawn in the Middle Ages. For example, worshipers were expected to visually consume the Host (the bread symbolizing Christ’s body) during Mass, as full communion was reserved for Easter only.

Saints and relics

Since the fifth century, saints’ relics (fragments of venerated holy persons) were embedded in the altar, so it is not surprising that altarpieces were often dedicated to saints and the miracles they performed. Italy in particular favored portraits of saints flanked by scenes from their lives, as seen, for example, in the image of St. Francis of Assisi by Bonaventura Berlinghieri in the Church of San Francesco in Pescia.

The Virgin Mary and the Incarnation of Christ were also frequently portrayed, though the Passion of Christ (and his resurrection) most frequently provided the backdrop for the mystery of Transubstantiation celebrated on the altar. The image could be painted or sculpted out of wood, metal, stone, or marble; relief sculpture was typically painted in bright colors and often gilded.

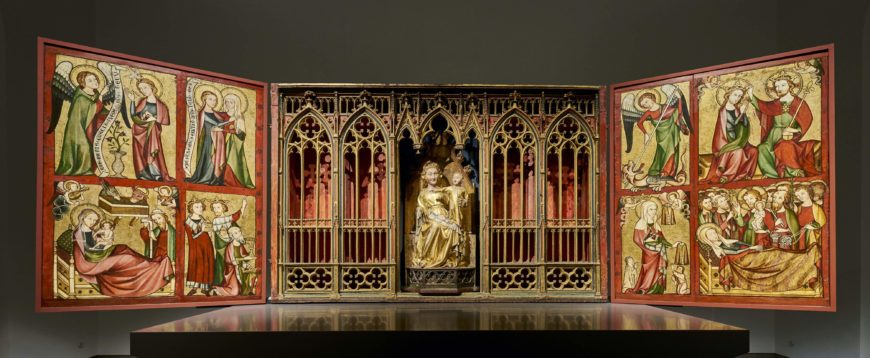

Germany, the Low Countries, and Scandinavia were most often associated with polyptychs (many-paneled works) that have several stages of closing and opening, in which a hierarchy of different media from painting to sculpture engaged the worshiper in a dance of concealment and revelation that culminated in a vision of the divine.

For example, the altarpiece from Altenberg contained a statue of the Virgin and Christ Child which was flanked by double-hinged wings that were opened in stages so that the first opening revealed painted panels of the Annunciation, Nativity, Death and Coronation of the Virgin (image above). The second opening disclosed the Visitation, Adoration of the Magi, and the patron saints of the Altenberg cloister, Michael and Elizabeth of Hungary. When the wings were fully closed, the Madonna and Child were hidden and painted scenes from the Passion were visible.

Variations

English parish churches had a predilection for rood screens, which were a type of carved barrier separating the nave (the main, central space of the church) from the chancel. Altarpieces carved out of alabaster became common in fourteenth-century England, featuring scenes from the life of Christ; these were often imported by other European countries.

The abbey of St.-Denis in France boasted a series of rectangular stone altarpieces that featured the lives of saints interwoven with the most important episodes of Christ’s life and death. For example, the life of St. Eustache unfolds to either side of the Crucifixion on one of the altarpieces, the latter of which participated in the liturgical activities of the church and often reflected the stained-glass subject matter of the individual chapels in which they were found.

Gothic beauty

In the later medieval period in France (15th–16th centuries), elaborate polyptychs with spiky pinnacles and late Gothic tracery formed the backdrop for densely populated narratives of the Passion and resurrection of Christ. In the seven-paneled altarpiece from the church of St.-Martin in Ambierle, the painted outer wings represent the patrons with their respective patron saints and above, the Annunciation to the Virgin by the archangel Gabriel of the birth of Christ. On the outer sides of these wings, painted in grisaille are the donors’ coats of arms.

Turrets (towers) crowned by triangular gables and divided by vertical pinnacles with spiky crockets create the framework of the polychromed and gilded wood carving of the inner three panels that house the story of Christ’s torture and triumph over death against tracery patterns that mimic stained glass windows found in Gothic churches.

To the left, one finds the Betrayal of Christ, the Flagellation, and the Crowning with the Crown of Thorns — scenes that led up to the death of Christ. The Crucifixion occupies the elevated central portion of the altarpiece, and the Descent from the Cross, the Entombment, and Resurrection are represented on the right side of the altarpiece.

There is an immediacy to the treatment of the narrative that invites the worshiper’s immersion in the story: anecdotal detail abounds, the small scale and large number of the figures encourage the eye to consume and possess what it sees in a fashion similar to a child’s absorption before a dollhouse. The scenes on the altarpiece are made imminently accessible by the use of contemporary garb, highly detailed architectural settings, and exaggerated gestures and facial expressions.

One feels compelled to enter into the drama of the story in a visceral way—feeling the sorrow of the Virgin as she swoons at her son’s death. This palpable quality of empathy that propels the viewer into the Passion of Christ makes the historical past fall away: we experience the pathos of Christ’s death in the present moment.

According to medieval theories of vision, memory was a physical process based on embodied visions. According to one twelfth-century thinker, they imprinted themselves upon the eyes of the heart. The altarpiece guided the faithful to a state of mind conducive to prayer, promoted communication with the saints, and served as a mnemonic device for meditation, and could even assist in achieving communion with the divine.

The altar had evolved into a table that was alive with color, often with precious stones, with relics, the chalice (which held the wine) and paten (which held the Host) consecrated to the blood and body of Christ, and finally, a carved and/or painted retable: this was the spectacle of the holy.

As Jean-Claude Schmitt put it:

this was an ensemble of sacred objects, engaged in a dialectic movement of revealing and concealing that encouraged individual piety and collective adherence to the mystery of the ritual.J.-C. Schmitt , “Les reliques et les images,” in Les reliques: Objets, cultes, symbols (Turnhout: 1999)

The story embodied on the altarpiece offered an object lesson in the human suffering experienced by Christ. The worshiper’s immersion in the death and resurrection of Christ was also an engagement with the tenets of Christianity, poignantly transcribed upon the sculpted, polychromed altarpieces.

Additional resources

Hans Belting, Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image before the Era of Art, trans. Edmond Jephcott (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994).

Paul Binski, “The 13th-Century English Altarpiece,” in Norwegian Medieval Altar Frontals and Related Materials. Institutum Romanum Norvegiae, Acta ad archaeologiam et atrium historiam pertinentia 11, pp. 47–57 (Rome: Bretschneider, 1995).

Shirley Neilsen Blum, Early Netherlandish Triptychs: A Study in Patronage (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1969).

Marco Ciatti, “The Typology, Meaning, and Use of Some Panel Paintings from the Duecento and Trecento,” in Italian Panel Painting of the Duecento and Trecento, ed. Victor M. Schmidt, 15–29. Studies in the History of Art 61. Center for the Advanced Study in the Visual Arts. Symposium Papers 38 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002).

Donald L. Ehresmann, “Some Observations on the Role of Liturgy in the Early Winged Altarpiece,” Art Bulletin 64/3 (1982), pp. 359–69.

Julian Gardner, “Altars, Altarpieces, and Art History: Legislation and Usage,” in Italian Altarpieces 1250–1500: Function and Design, ed. Eve Borsook and Fiorella Superbi Gioffredi, 5–39 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994).

Peter Humfrey and Martin Kemp, eds., The Altarpiece in the Renaissance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

Lynn F. Jacobs, “The Inverted ‘T’-Shape in Early Netherlandish Altarpieces: Studies in the Relation between Painting and Sculpture” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 54/1 (1991), pp. 33–65.

Lynn F. Jacobs, Early Netherlandish Carved Altarpieces, 1380–1550: Medieval Tastes and Mass Marketing (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Justin E.A. Kroesen and Victor M. Schmidt, eds., The Altar and its Environment, 1150–1400 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2009).

Barbara G. Lane, The Altar and the Altarpiece: Sacramental Themes in Early Netherlandish Painting (New York: Harper & Row, 1984).

Henning Laugerud, “To See with the Eyes of the Soul, Memory and Visual Culture in Medieval Europe,” in ARV, Nordic Yearbook of Folklore Studies 66 (Uppsala: Swedish Science Press, 2010), pp. 43–68.

Éric Palazzo, “Art and the Senses: Art and Liturgy in the Middle Ages,” in A Cultural History of the Senses in the Middle Ages, ed. Richard Newhauser, pp. 175–94 (London, New Delhi, Sidney: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014).

Donna L. Sadler, Touching the Passion—Seeing Late Medieval Altarpieces through the Eyes of Faith (Leiden: Brill, 2018).

Beth Williamson, “Altarpieces, Liturgy, and Devotion,” Speculum 79 (2004): 341–406.

Beth Williamson, “Sensory Experience in Medieval Devotion: Sound and Vision, Invisibility and Silence,” Speculum 88 1 (2013), pp. 1–43.

Kim Woods, “The Netherlandish Carved Altarpiece c. 1500: Type and Function,” in Humfrey and Kemp, The Altarpiece in the Renaissance, pp. 76–89.

Kim Woods, “Some Sixteenth-Century Antwerp Carved Wooden Altar-Pieces in England,” Burlington Magazine 141/1152 (1999), pp.144–55.

Do you speak Renaissance? Carlo Crivelli, Madonna and Child

by DR. LAUREN KILROY-EWBANK and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Carlo Crivelli, Madonna and Child, c. 1480, tempera and gold on wood, 37.8 x 25.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art).

A conversation between Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank and Dr. Steven Zucker.

Test yourself with a quiz!

QUIZ NEEDED HERE

Additional resources:

This painting at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Paintings by Crivelli at The National Gallery

Ronald Lightbown, Carlo Crivelli (Yale University Press, 2004)

Ornament and Illusion: Carlo Crivelli of Venice (Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, 2015)

Why commission artwork during the renaissance?

by DR. LAUREN KILROY-EWBANK and DR. HEATHER GRAHAM

What’s in it for me?

Why would someone patronize art in the renaissance? Giovanni Rucellai, a major patron of art and architecture in fifteenth-century Florence, paid Leon Battista Alberti to construct the Palazzo Rucellai and the façade of Santa Maria Novella, both high–profile and extremely costly undertakings. In his personal memoir, he talks about his motivations for these and other commissions, noting that “All the above-mentioned things have given and give me the greatest satisfaction and pleasure, because in part they serve the honor of God as well as the honor of the city and the commemoration of myself.” [1]

Aside from bringing honor to one’s faith, city, and self, patronizing art was also fun. Earning and spending money felt good, especially the spending part. As Rucellai goes on, “I really think that it is even more pleasurable to spend than to earn….” [2]

The ancient Roman world (with which much of renaissance Europe was endlessly fascinated) also provided motivation for patronage. The liberal expenditure on art and architecture by ancient Roman patricians was celebrated in the literature of antiquity and survived—even if in fragmentary form—to dazzle the eyes of renaissance viewers. The Roman Emperor Augustus, who so famously said that he found Rome a city of brick and transformed it into a city of marble, provided the ultimate noble model of patronage.

Self-fashioning

Commissioning an artwork often meant giving detailed directions to the artist, even what to include in the work, and this helped patrons fashion their identities. While the identity of Bronzino’s Florentine sitter in a Portrait of a Young Man is unknown, the artist shows him standing confidently in the composition’s center, looking out at us while dressed in expensive black satin, slashed sleeves, and a codpiece complete with golden aglets. He holds his fingers between the pages of a poetry book, which rests atop a table carved with grotesque faces. The book and the table were undoubtedly intended to convey the man’s sophistication and learning while his clothing and upright posture showed his wealth and nobility.

The renaissance was also a time when increasingly wealthy middle-class merchants and others aspired to increase their social recognition and began to commission portraits, as we see in double portraits like Jan van Eyck’s The Arnolfini Portrait showing the Italian merchant Giovanni de Nicolao di Arnolfini with his wife in Bruges (in present-day Belgium). Petrus Christus’s Portrait of a Carthusian reveals the increasing prominence of religious figures, with clergy, monks, and nuns sitting for portraits, many of which were likely made to celebrate the entry of wealthy individuals into religious orders.

Wealth, power, and status

In a seventeenth-century fresco by the artist Ottavio Vannini, Michelangelo, the artist, is shown presenting the powerful Florentine, Lorenzo the Magnificent de’ Medici, with a sculpture of a faun. Lorenzo sits at the center of the image, facing frontally like a ruler, while Michelangelo stands off to the side, bowing respectfully towards him. While today the name Michelangelo is better known, in the fresco the Medici patron is shown as more important than the artist.

Paying for something lavish and monumental, such as Sant’Andrea in Mantua (commissioned by Ludovico Gonzaga, ruler of the Italian city-state of Mantua and built by Alberti) or El Escorial (commissioned by Philip II, King of Spain, outside of Madrid), was a powerful statement about a patron’s wealth and status. Philip II was deeply involved in the planning of the massive complex that became El Escorial (a monastery, palace, and church). The complex was built in an austere, classicizing style that was intended to showcase Philip’s imperial power by looking to ancient Roman architectural forms.

Spiritual comfort and salvation

Some patrons paid for art to serve a larger purpose, perhaps to fulfill a devotional or religious need, as the Isenheim Altarpiece did for people suffering from the painful disease of ergotism. Others commissioned art to expiate the patron’s sins for such things as usury, as Jodocus Vijd desired when he paid a large sum of money for the Ghent Altarpiece.

Inspiring civic duty and responsibility

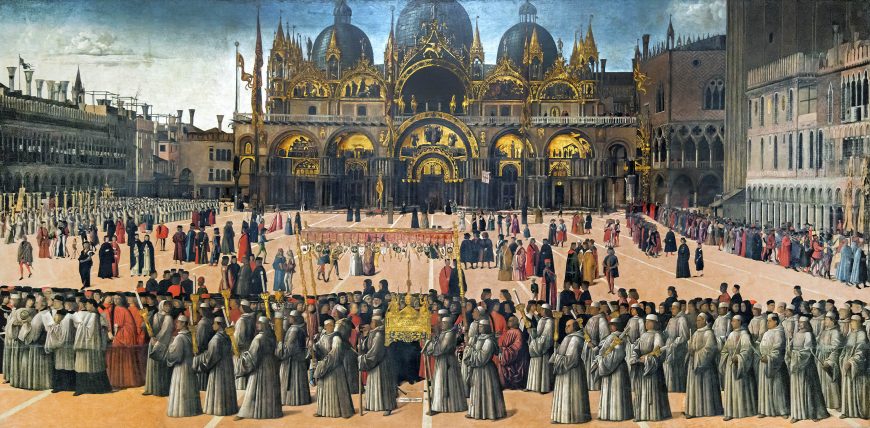

Commissioning artworks also helped to inspire civic responsibility or to demonstrate that members of a particular community performed their duties properly. The Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista, one of many Venetian devotional confraternities, paid Gentile Bellini to depict the procession of the relic of the True Cross through St. Mark’s square. This commission highlights the importance of the miraculous object as well as the civic duty of the city’s citizens, who are shown in the painting’s foreground, with the Scuola members carrying a canopy above the relic.

Patrons in art

Patrons often had themselves incorporated into paintings and sculptures to remind viewers of who had paid for the work of art as well as to show themselves participating in the narrative. We call these “donor portraits.” Lluis Dalmau’s Virgin of the Councillors, for instance, shows the Virgin Mary enthroned, holding the baby Jesus and surrounded by saints in a luxurious Gothic interior. Kneeling before the saints, at the edge of the throne, are five men, all of whom were members of the Barcelona City Council (Casa de la Ciutat), who had paid Dalmau to create the painting to hang in the chapel at the council palace. The portrait collapses sacred and secular time, placing the men as perpetually revering Mary and showcasing their piety to anyone observing the painting.

Even in instances where patrons were not overtly depicted in artworks, artists would sometimes be directed to include heraldic symbols, visual puns, or other motifs to allude to the patron. The coat of arms of the wealthy Mendoza family rests above main entrance to the Palacio del Infantado (in Guadalajara, Spain) amidst the decorative plateresque elements, and advertising to any passersby who had paid for and lived in the striking palace.

Patrons as influencers

Patrons also set fashions for style and subject matter. Importing artists and artworks from distant lands could show off one’s sophistication and introduce new styles, techniques, and subjects to local audiences. Artists and art traveled widely during this period, and exchanges across Europe and beyond were common. Because of the wealth and glamour of northern European court culture, it was fashionable for the wealthy elite of Italy and Spain to import both Netherlandish art and artists. Queen Isabel of Castile, whose father had favored Flemish painters such as Rogier van der Weyden, had a number of artists, including Juan de Flandes, Michel Sittow, and Gil de Siloe, at her court to create lavish works that would speak to her power and magnificence.

Likewise, Tomasso Portinari, who worked for the Medici bank in Bruges, hired the northern artist Hugo van der Goes to paint a massive altarpiece of the Nativity for his home town of Florence, Italy. When put on display in the hospital church of Santa Maria Nuova in 1483, it created a sensation. Italian artists, in awe of the accomplishments of the northern master, quickly responded to what they saw. Portinari not only showcased his own cosmopolitan sophistication, he also helped shape the direction of Florentine art by introducing this spectacular image to local artists.

Why patrons matter

Art communicated ideas about patrons. Status, wealth, social, and religious identities all played out across paintings, prints, sculptures, and buildings. At the same time, the careers of artists were shaped with the aid of powerful patrons. Likewise, artistic styles emerged or developed as a result of patrons hiring artists or buying artworks and by transporting them to new locations. The history of art has been shaped not only by artists, but also by the patrons whose choices in sponsorship determined what art was created, who created it, who saw it, and what art was made of. Until the modern era, the stories that have been told in art are the stories that reflect the interests of the rich and powerful, the privileged few—mostly men—who were in positions to patronize art. In a nutshell, patronage mattered.

Notes:

[1] Giovanni Rucellai, Giovanni Rucellai ed il suo Zibaldone, ed. Alessandro Perosa. 2 vols. (London: The Warburg Institute, University of London, 1960), 1:121

[2] Rucellai, Zibaldone, 1:121

Additional resources

Read more about Isabella d’Este and her patronage

Learn more about patronage in fifteenth-century Burgundy

Explore renaissance Spain further, and learn more about the patronage of Queen Isabel of Castile

Learn more about Patrons and Artists in Late 15th-Century Florence from the National Gallery of Art

Read about patronage at the later Valois court on the Heilbrunn Timeline

Art from the Court of Burgundy: The Patronage of Philip the Bold and John the Fearless 1364–1419 (Dijon, 2004)

Michael Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy: A Primer in the Social History of Pictorial Style, 2d ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988)

Rafael Domínguez Casas, “The Artistic Patronage of Isabel the Catholic: Medieval or Modern?,” in Queen Isabel I of Castile: Power, Patronage, Persona, edited by Barbara F. Weissberger (Boydell & Brewer, 2008), pp. 123–48

Alison Cole, Virtue and Magnificence: Art of the Italian Renaissance Courts (New York: H. N. Abrams, 1995)

Tracy E. Cooper, “Mecenatismo or Clientelismo? The Character of Renaissance Patronage,” in The Search for a Patron in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, edited by David G. Wilkins and Rebecca L. Wilkins (Medieval and Renaissance Studies 12. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen, 1996), pp. 19–32

Mary Hollingsworth, Patronage in Renaissance Italy: From 1400 to the Early Sixteenth Century (London: Thistle, 2014)

Robrecht Janssen, Jan van der Stock, and Daan van Heesch, Netherlandish Art and Luxury Goods in Renaissance Spain: Studies in Honor of Professor Jan Karel Steppe (1918–2009) (Belgium: Harvey Miller Publishers, 2018)

Dale Kent, Cosimo De’ Medici and the Florentine Renaissance: The Patron’s Oeuvre (New Haven: Yale UP, 2000)

Catherine E. King and Margaret L King, Renaissance Women Patrons: Wives and Widows in Italy, C. 1300–1550 (Manchester: Manchester UP, 1998)

Sherry C. M. Lindquist, Agency, Visuality and Society and the Charterhouse of Champmol (Aldershot and Burlington, 2008)

Michelle O’Malley, The Business of Art: Contracts and the Commissioning Process in Renaissance Italy (New Haven: Yale UP, 2005)

Sheryl Reiss, “A Taxonomy of Art Patronage in Renaissance Italy,” in A Companion to Renaissance and Baroque Art, ed. Babette Bohn and James M. Saslow (Chichester, West Sussex UK: John Wiley & Sons, 2013), pp. 23–43

Hugo Van der Velden, The Donor’s Image: Gerard Loyet and the votive portraits of Charles the Bold (Turnhout, 2000)

Jessica Weiss, “Juan de Flandes and His Financial Success in Castile,” Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 11:1 (Winter 2019) DOI: 10.5092/jhna.2019.11.1.2

Types of renaissance patronage

by DR. LAUREN KILROY-EWBANK and DR. HEATHER GRAHAM

When the banker’s guild of Florence commissioned a massive bronze statue of St. Matthew for Orsanmichele—a former grain house turned shrine at the heart of the city—they clearly had their own magnificence in mind. Not only did they hire the highly in-demand sculptor, Lorenzo Ghiberti, to create it, but they also stipulated in the work’s contract that it must be as big or bigger than the sculptor’s creation for a rival guild in the same location. They also wanted it to be cast from no more than two pieces (a difficult feat!). Ghiberti’s fame, the statue’s scale, and the technical proficiency required to cast it were all reflections of the banker’s guild’s own status.

Why is it important to know about patrons?

While today we often focus on the artist who made an artwork, in the renaissance it was the patron—the person or group of people paying for the image—who was considered the primary force behind a work’s creation. We often forget that for most of history artists did not simply create art for art’s sake. Information about patrons provides a window into the complex process involved in the production of art and architecture. Patrons often dictated the cost, materials, size, location, and subject matter of works of art.

Knowing about patronage also demonstrates the various ways that people used art to communicate ideas about themselves, how styles or subjects were popularized, and how artists’ careers were fostered. Patrons were far more socially and economically powerful than the artists who served them. A work of art was considered a reflection of the patron’s status, and much of the credit for the ingenuity or skill with which an art object was created was given to the savvy patron who hired well. Still, an artist’s social status and reputation could also benefit from the support of a powerful patron.

Defining our terms

A closer look at terminology helps us to understand how patronage was understood in the renaissance. The English term “patron” comes from the Latin word patronus, meaning protector of clients or dependents, specifically freedmen. The term patronus, in turn, is related to pater, meaning father. Like the father of a family, or the protector of dependents, a patron was responsible for the conception and realization of a work of art. The relationship of patronage of art and architecture to ideas about fatherhood reflects the patriarchal order of renaissance society. As the wealthy Florentine banker Giovanni Rucellai once noted: “Men have two roles to perform in life: to procreate and to build.” [1] Just as men held primary social and political power, attitudes towards artistic patronage also saw it as a masculine pursuit.

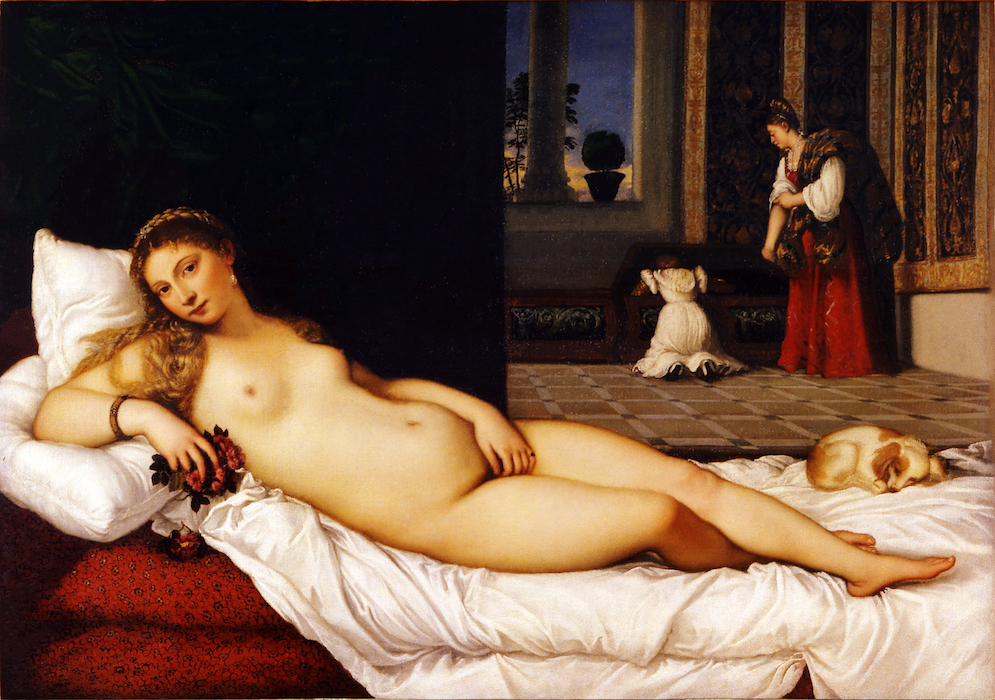

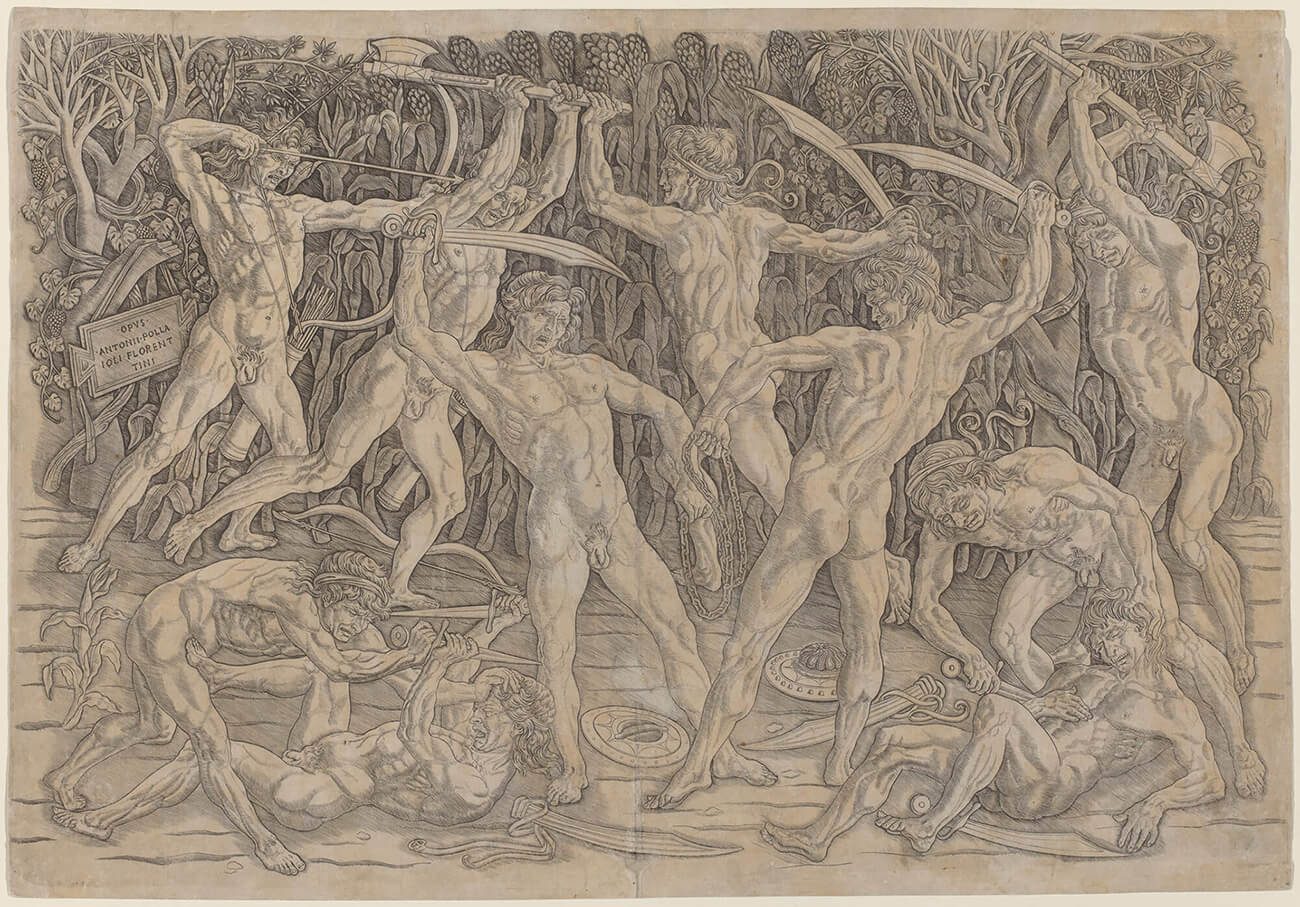

While both men and women commissioned art, the cost and public nature of the art market meant that most women were not in a social or financial position to act as patrons. Not only did men commission far more art than women, but also they tended to commission art that was more expensive, like sculpture and architecture, and more daring in subject matter, like mythological scenes and nudes. While laws pertaining to women’s financial independence varied across Europe, the vast majority of women had limited funds at their disposal for freely commissioning art.

Even women at the top of the social hierarchy, like the Marchioness of Mantua, Isabella d’Este, who was one of the most prolific female patrons of the renaissance, commanded far smaller sums than their male peers. With few exceptions, women’s patronage, in keeping with their primarily domestic and maternal roles in society, was often limited to religious painting and imagery that celebrated their husbands and sons.

How do we study patronage?

To study patronage we have to consider the broader context for the creation of art. Economics, politics, social and cultural formations, and psychology—these areas (among others) all inform the way we understand why people hired artists to make specific types of images and structures. To study these choices we look at two main types of evidence: written and visual. Written documents might include contracts, letters, diary entries, and inventories. Visual documentation includes donor portraits (images where the features of the patron are included in the work), inscriptions, coats of arms, and other imagery that represents the family or the community of the person or people paying.

Rogier van der Weyden’s famous Deposition, painted for the archer’s guild of Leuven for a public setting, includes miniature crossbows at the upper corners of the composition as a direct allusion to the patrons. This inclusion helps us to understand the multiple motivations for commissioning this work—it was intended both to honor God and to commemorate those who paid for it.

Ghiberti’s St Matthew and van der Weyden’s Deposition are both public works of art commissioned by groups of patrons. We can roughly break renaissance patronage into two main categories:

- Public: Although the boundaries between public and private were fluid, in general a public work of art was intended for display outside the home to a broad, public audience. This includes art in churches, town squares, and public buildings, and imagery like prints that circulated in multiples.

- Private: “Private” art was limited in audience and generally displayed in the home. Of course, some homes were more private than others. The home of a wealthy merchant or a ruler might serve (as the U.S. White House does today) as a semi-public space where business was conducted and a wider audience was reached.

The works discussed above are also both examples of religious imagery. There are two main types of renaissance art that one might pay for:

- Religious: This includes imagery for both public and private use that relates to a particular faith. Christianity was the predominant faith throughout Europe during the renaissance.

- Secular: This means non-religious imagery and includes portraiture, scenes taken from history or literature, and mythological subjects.

Of course, like the difference between public and private, there was much overlap between religious and secular. Funerary or memorial imagery is a good example: a portrait (secular) of the deceased might be placed within a tomb monument that includes the Virgin and Christ Child (religious) as well as forms and figures borrowed from ancient (secular) art. Michelangelo’s tomb for Pope Julis II (completed 1545), for example, includes a full body portrait of the deceased and numerous religious figures, all placed within a sculpted framework borrowing forms from ancient Roman sarcophagi and buildings.

While all renaissance patrons of art enjoyed a certain amount of wealth and social privilege, patronage could be a personal or a collective endeavour. Both the St. Matthew and the Deposition were commissioned by groups of men who were members of powerful guilds, or the corporate entities that dominated renaissance public life. Other types of patrons included rulers, nobles, members of the clergy, merchants, confraternities, nuns, and monks. It is important for us to keep in mind these different types of patronage because they help us understand the motivations of the patron as well as the possible functions of the artwork itself.

Notes:

[1] Giovanni Rucellai, Giovanni Rucellai ed il suo Zibaldone, ed. Alessandro Perosa. 2 vols. (London: The Warburg Institute, University of London, 1960), 2:13

Additional resources

Why commission artwork during the Renaissance

Learn more about patronage in fifteenth-century Burgundy

Explore renaissance Spain further, and learn more about the patronage of Queen Isabel of Castile

Learn more about Patrons and Artists in Late 15th-Century Florence from the National Gallery of Art

Read about patronage at the later Valois court on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Art from the Court of Burgundy: The Patronage of Philip the Bold and John the Fearless 1364–1419 (Dijon, 2004)

Michael Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy: A Primer in the Social History of Pictorial Style, 2d ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988)

Rafael Domínguez Casas, “The Artistic Patronage of Isabel the Catholic: Medieval or Modern?,” in Queen Isabel I of Castile: Power, Patronage, Persona, edited by Barbara F. Weissberger (Boydell & Brewer, 2008), pp. 123–48

Alison Cole, Virtue and Magnificence: Art of the Italian Renaissance Courts (New York: H. N. Abrams, 1995)

Tracy E. Cooper, “Mecenatismo or Clientelismo? The Character of Renaissance Patronage,” in The Search for a Patron in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, edited by David G. Wilkins and Rebecca L. Wilkins (Medieval and Renaissance Studies 12. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen, 1996), pp. 19–32

Mary Hollingsworth, Patronage in Renaissance Italy: From 1400 to the Early Sixteenth Century (London: Thistle, 2014)

Robrecht Janssen, Jan van der Stock, and Daan van Heesch, Netherlandish Art and Luxury Goods in Renaissance Spain: Studies in Honor of Professor Jan Karel Steppe (1918–2009) (Belgium: Harvey Miller Publishers, 2018)

Dale Kent, Cosimo De’ Medici and the Florentine Renaissance: The Patron’s Oeuvre (New Haven: Yale UP, 2000)

Catherine E. King and Margaret L King, Renaissance Women Patrons: Wives and Widows in Italy, C. 1300–1550 (Manchester: Manchester UP, 1998)

Sherry C. M. Lindquist, Agency, Visuality and Society and the Charterhouse of Champmol (Aldershot and Burlington, 2008)

Michelle O’Malley, The Business of Art: Contracts and the Commissioning Process in Renaissance Italy (New Haven: Yale UP, 2005)

Sheryl Reiss, “A Taxonomy of Art Patronage in Renaissance Italy,” in A Companion to Renaissance and Baroque Art, ed. Babette Bohn and James M. Saslow (Chichester, West Sussex UK: John Wiley & Sons, 2013), pp. 23–43

Hugo Van der Velden, The Donor’s Image: Gerard Loyet and the votive portraits of Charles the Bold (Turnhout, 2000)

Female artists in the renaissance

by DR. DEANNA MACDONALD

Recovering forgotten “masters”

When Renaissance painter Plautilla Nelli got her first solo exhibit at Florence’s Uffizi Gallery in 2017, some art historians asked . . . Plautilla who??

Despite being a celebrated artist in sixteenth-century Florence, Nelli had been forgotten by art history to the point that even scholars of Renaissance art knew nothing of her. How was this possible?

In a word, gender.

Nelli’s obscurity was the cumulative effect of historical gender imbalances that limited women in the Renaissance and modern art worlds. While the past cannot be changed, gender balance in contemporary scholarship and curatorial practice is bringing women Renaissance artists to light.

The Renaissance glass ceiling: then and now

As the Guerrilla Girls have highlighted, the art world has been male dominated. Nevertheless, women have always been artists, even famed artists. So why were many forgotten?

The brief answer is: many reasons. For instance, the academic study of art history evolved through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and the men who wrote it developed a canon of great artists and narratives that connected great art and masculinity. Male artists were the subjects of most books and research, and museums highlighted these well-known male artists. Art by women was often overlooked or considered as exceptions, and thus was more likely to fall into obscurity, disrepair, or museum storage. In some cases, art by an under-appreciated female artist was attributed to a better-known male artist.

Scholars are now pulling Renaissance women artists from obscurity, discovering how they succeeded in the gendered societies in which they worked.

Education was a key point. Much of Renaissance art revolves around learning – about classical antiquity, philosophy, anatomy, or mathematics, not to mention the skills learned as an apprentice in a professional art studio. But gender norms of the time meant women’s education rarely exceeded what was needed to be wives and mothers. With almost no opportunities for apprenticeships with master/male artists, women were at a disadvantage.

Yet, talented women did become artists under certain circumstances, such as:

- nuns in learned monasteries (e.g., Sister Plautilla Nelli is unusually well-documented. Though nuns were manuscript illuminators and painters since the middle ages, only a few names (e.g. Herard of Landsburg, St. Catherina of Bologna, Guda) are recorded.

- noble women with exceptional educations (e.g., Sofonisba Anguissola, Lucia Anguissola, but also most of the nuns above); or

- most commonly, women born into a family of artists (e.g., Levina Teerlinc, Catarina van Hemessen, Artemisia Gentileschi, Elisabetta Sirani, Lavinia Fontana)

In all cases, the public personae of women artists were closely tied to gendered ideas that expected a respectable woman to be virtuous, pious, and obedient to God and her father/husband. If an artist failed to meet these standards, it could mean the end of her career (such as the brief career of sculptor Properzia de’Rossi).

The nun artist: Plautilla Nelli (1524–1588)

“Nun Art” was considered to be exceptionally spiritual and the holy images of Sister Plautilla Nelli’s studio, such as this image of “St. Catherine with Lily,” were especially sought after by the Florentine elite. Nelli’s contemporary Giorgio Vasari notes that, “in the houses of gentlemen throughout Florence, there are so many [of Nelli’s] pictures, that it would be tedious to attempt to speak of them all.”

So how did this nun learn to paint like an angel? Like many daughters of wealthy families, 14-year-old Plautilla Nelli was placed in a convent. This was a cost-saving choice, as a convent dowry was less than a marriage dowry. Luckily for Nelli, her convent, Santa Caterina da Siena in Florence, encouraged its nuns not only to pray but also to learn and draw.

It is unclear how she learned to paint but Nelli became a prolific artist, overseeing a convent studio with perhaps as many as eight female nun followers. Her success was such that Vasari included Nelli as one of only four women among over 100 artists in his 1550 Lives of the Artists. Vasari notes that she is a “nun and now Prioress” who is “beginning little by little to draw and imitate in colour pictures and painting by excellent masters.” Vasari also notes that she could have been one of the greatest painters in the world if only she could have studied mathematics and anatomy as male artists did (something forbidden to women and especially a nun). [1]

Despite these gendered limitations, Nelli produced large-scale devotional paintings and manuscript illuminations for church and private commissions. Today, about twenty extant paintings by Nelli are known, including the largest and earliest known painting of the Last Supper by a woman.

Forgotten in storage for much of the twentieth century, Nelli’s Last Supper was restored with the help of the Advancing Women in the Arts Foundation (AWA) and in 2019 became part of the permanent display in the Museo di Santa Maria Novella in Florence.

Educated lady: Sofonisba Anguissola (1532–1625)

Sofonisba Anguissola’s self-portraits display the often contradictory virtues expected of a young noblewoman and of an artist. She presents herself as both modest maiden and virtuoso artist, as in this miniature portrait, probably made for a prospective patron. The medallion is inscribed in Latin: “The maiden Sofonisba Anguissola, depicted by her own hand, from a mirror, at Cremona.”

It was this talent, along with a spotless reputation and an exceptional education (facilitated by her impoverished but forward-thinking, nobleman father), that would help Anguissola become a painter at the court of King Philip II of Spain. Yet as men were court painters and Anguissola was a woman, she was given a title more appropriate to her gender: lady-in-waiting to Philip’s queen, Elizabeth of Valois.

These types of gendered adjustments allowed the Cremona-born artist to work at the highest level in the male world of court art. But these same adjustments may also have contributed to misattributions of Anguissola’s works. For instance, Anguissola’s 1565 Portrait of Philip II was mistakenly attributed to “court artist” Juan Pantoja de la Cruz from at least the seventeenth century, despite the fact that it strongly resembled her other known works. Only after scientific examinations in the 1990s was the work reattributed to Anguissola. Today the number of known works by Anguissola continues to rise, helped in part by a major exhibit at the Museo del Prado in 2019.

Artist’s daughter: Levina Teerlinc (1510?–1576)

Bruges-born artist Levina Teerlinc was among the highest paid and most prolific artists at the Tudor court in England for about thirty years but today only five or six works can tentatively be attributed to her hand. These all measure under a few centimeters.

Miniatures, or tiny detailed portraits, were a popular format made and given as keepsakes and gifts that could be viewed privately or worn as a pendant or brooch. In a pre-photography world, miniature portraits allowed individuals to distribute their own image to other people in an intimate format. And few wanted more portraits than the nobles of the Tudor court, in part because portraits offered highly curated images reflecting contemporary styles and status. The Portrait Miniature of Lady Katherine Grey is typical of Teerlinc’s work. With meticulous and flattering detail, she paints the fashionable cousin of, and once a possible successor to, Queen Elizabeth I.

Teerlinc was a master miniaturist and manuscript illuminator. She was trained in the studio of her father, celebrated Flemish painter Simon Bening. When she arrived in England with her husband around 1546, Levina Teerlinc took up the role of “royal paintrix,” first at the court of Henry VIII and successively for Edward VI, Mary I, and Elizabeth I. Part of the royal household, she painted not only aristocratic portraits but numerous other works today only known from court inventories. Her high status at court is reflected in her annual salary: a remarkable forty pounds a year, which was four times the average annual earnings for a skilled tradesman and ten pounds more than the salary of her male predecessor as court artist, Hans Holbein.

A 21st-century renaissance

Michelangelo, Leonardo, and the famed male artists of the Renaissance deservedly remain central figures in art history. But they are only half the story. Despite obstacles, women were exceptional artists in the Renaissance. Today’s task is to continue to recover them from the dusty back shelves, storage rooms, and the past indifference of art history.

Notes:

- Giorgio Vasari, The Lives of the Artists, trans. Julia Conway Bondanella and Peter Bondanella (London: Oxford University Press, 1991), 342.

Additional resources:

Read more about Plautilla Nelli on Advancing Women Artists

Watch a video about the restoration of Nelli’s Last Supper

Learn more about Sofonisba Anguissola’s Boy at the Spanish Court at the San Diego Museum of Art

Fausta Navarro, Plautilla Nelli: arte e devozione sulle orme di Savonarola = Plautilla Nelli: Art and Devotion in Savonarola’s Footsteps (Livorno : Sillabe, 2017)

Sheila Barker, Women Artists in Early Modern Italy: Careers, Fame, and Collectors (London: Harvey Miller Publishers, an imprint of Brepols Publishers, 2016)

Leticia Ruiz Gómez, A Tale of Two Women Painters: Sofonisba Anguissola and Lavinia Fontana (Madrid: Museo del Prado exhibit catalogue, 2019)

The National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington DC. n.d. “Artist profiles.”

Images of African Kingship, Real and Imagined

by DR. KRISTEN COLLINS and DR. BRYAN C. KEENE

The exhibition Balthazar: A Black African King in Medieval and Renaissance Art examines the figure of the Black king, an artistic invention arrived at by Europeans painting during the 1400s.

Nativity (or crèche) scenes from the Middle Ages to today often include three kings (or magi) bringing gifts to the infant Jesus. Often, these scenes include a Black king, sometimes referred to by the name Balthazar (his two traveling companions are known as Caspar and Melchior).

European Christian tradition often referred to Balthazar as coming from Africa, and maps from the time reveal a combination of fantasy, desire, and lived encounters with Africa and African people.

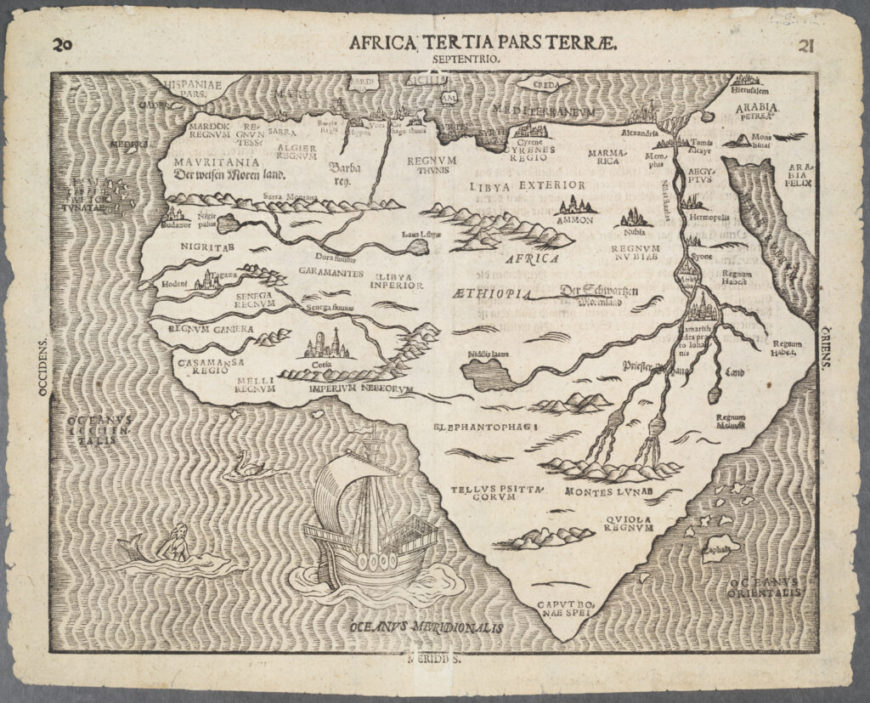

In 1597, German Protestant scholar and cartographer Heinrich Bünting designed a map of Africa marked by both real and imagined kingdoms. In West Africa, we encounter the realm of the Muslim king Mansa Musa of Mali, who was famous for wealth and piety.

Mediterranean North Africa features numerous cultures, including kingdoms in Tunis and Egypt (visible on the map above). In East Africa, near the horn of the continent, we read the name of the legendary Christian king Prester John, who was said to reign in Ethiopia or India—reflecting Europeans’ imprecise understanding of world geography at the time. Beginning in the 1440s, Portuguese sailors embarked on searches for Prester John and his mythical kingdom, violently enslaving non-Christian Black Africans along the way.

The mythical Prester John and images of Balthazar reveal European fantasies about Africa and the wealth of kingdoms there. Below we look at three rulers from premodern Africa, each of whom had a major impact on the politics, economy, religion, and culture of the time. We also wish to acknowledge the presence of free Africans living in Europe during this period.

The continent of Africa is vast and was home to more kingdoms than premodern Europeans imagined, and to more than we’re exploring here. While histories of Afro-European contact have traditionally focused on the three faiths of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, Africa was home to many other literate and oral religions and traditions.

Mansa Musa: The Wealthiest Person in the History of the World

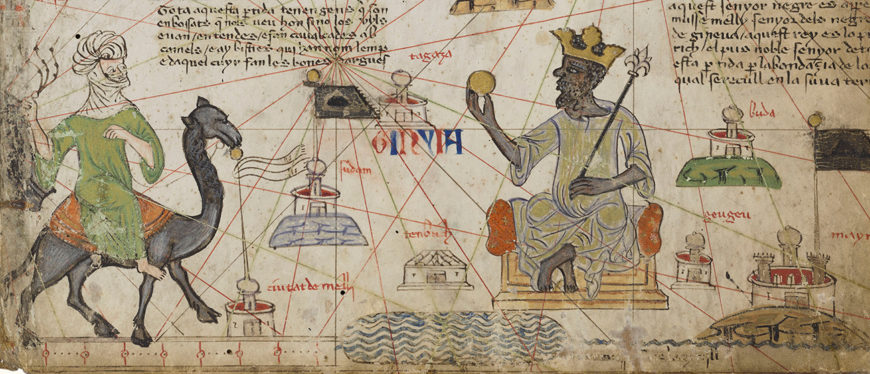

The map of Africa, Europe, and Asia above was created by the Spanish Jewish cartographer Abraham Cresques. It contains a rare medieval depiction of Mansa Musa, who ruled the West African Mali Empire, a territory the covered parts of present-day Mauritania and Mali, from 1312 to 1337. Mansa Musa’s holdings in gold were so great that to this day he is unsurpassed in personal wealth.

A pious Muslim who embraced charitable almsgiving as one of the five pillars of Islam, Mansa Musa made the hajj (pilgrimage) to Mecca with an entourage reportedly consisting of 60,000 subjects, 80 camels, and thousands of pounds of gold dust. His donations to the poor and diplomatic gifts along the way pumped so much gold into the economy of the Mediterranean that it devalued gold currency in the wealthy European mercantile cities such as Florence for decades.

The 14th-century Arab scholar Ibn Fadl Allah al-Umari lived in Cairo at the time and later reported on the ruler in his encyclopedia: “This man flooded Cairo with his gifts. He left no court emir nor holder of a royal office without the gift of a load of gold. The people here profited greatly from him and from his entourage in buying, selling, giving, and taking. They traded gold until these lessened its value in Egypt, making its price fall…”

Sultan Qaitbay: Mediterranean Diplomacy with Muslim African Rulers

Italian artists from Florence to Venice traveled frequently throughout the Mediterranean to broker political, religious, and mercantile partnerships with their Muslim neighbors. One powerful individual in the 1400s was the Mamluk sultan of Egypt called Qaitbay, who reigned from 1468 to 1496.

An anonymous Venetian painter depicted a reception scene in Damascus, Syria, between Europeans and representatives of the sultan, whose escutcheon is emblazoned on the gates of the city in the painting. “Glory to our Sultan, the master, the king of kings, the wise, the ruler, the just al-Ashraf Abu al-Nasr Qaitbay, the Sultan of Islam,” reads the gilded inscription, proclaiming the sovereignty of Qaitbay. His dominions stretched from the Nile basin of the southeastern Mediterranean to Israel, Syria, and Saudi Arabia.

Like Mansa Musa, Qaitay made a pilgrimage to Mecca and as an act of piety, he commissioned brass candlesticks for the shrine of the Prophet Muhammad in Medina. Architectural monuments built under his reign are still major destinations for curious travelers and the faithful alike.

Qaitbay’s diplomatic relationships included the wealthy Medici merchants in Florence, who received rare and valuable gifts from the Sultan. The most notorious gift that the sultan sent to the Tuscan city-state was a giraffe, which was memorialized in works of art, including a fresco of The Adoration of the Magi by Ghirlandaio in the church of Santa Maria Novella. The arrival of the giraffe with a retinue of Egyptian delegates may have evoked the pageantry of gift-giving reenacted in the annual magi processions in Florence, commemorated each January 6 on epiphany day.

For Qaitbay, such relationships with the Italian courts could lead to financial and military support against their shared rival in the northeastern Mediterranean: the Ottoman Turks. European princes and popes also feared Ottoman expansion and thus maintained ties with the Mamluks. Trade goods from Egypt—including metalwork, manuscripts (from Coptic Christian and Muslim communities), and glassware—had a great impact on European art at the time.

Zar’a Ya’eqob and the Medieval Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia

Ethiopia has a long history as a powerful Christian kingdom, as an empire, and later, as a nation. By the end of the third century, the four great powers of the ancient world were considered to be Rome, Persia, China, and the African kingdom of Axum—which occupied parts of present-day Eritrea and northern Ethiopia.

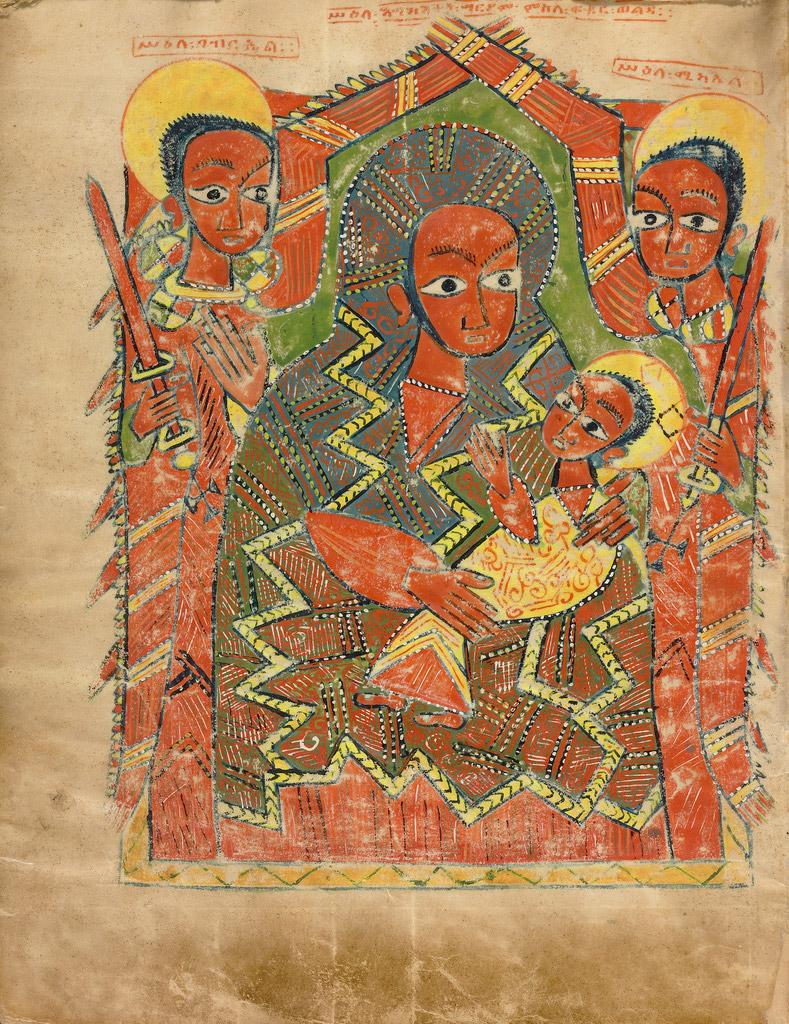

The later kingdom of Ethiopia, an early adopter of Christianity, developed a vibrant artistic tradition that included rock-hewn churches, illuminated manuscripts, and liturgical crosses. In the 15th century, successive Ethiopian nägäst (rulers) sent church delegations to Italy in an attempt to forge alliances, both religious and military, with Rome.

The 15th-century Ethiopian emperor Zar’a Ya’eqob was known for his strength and diplomacy. Zar’a Ya’eqob, who reigned from 1434 to 1468, resolved a major internal theological strife, a debate over the observance of the Sabbath (holy day of worship) that had been waged for over a century prior to his rule. It was also during his reign that the 1441 delegation joined the Council of Florence, one of the great church gatherings of that century. In Florence, his subjects were perplexed at Europeans’ continued identification of Zar’a Ya’eqob with the legendary priest-king Prester John.

At home, Zar’a Ya’eqob reportedly had an honor guard that stood to either side of his throne, holding drawn swords. The opening image of a Gospel book made at the Gunda Gunde monastery shows the Virgin Mary and Christ child similarly flanked by the archangels Michael and Gabriel. The Ethiopian kingdom had been Christian since the fourth century, but Zar’a Ya’eqob had Muslim subjects as well. The emperor’s wife, Eleni, was a Muslim convert and she continued to rule and exert significant influence after Zar’a Ya’eqob’s death.

Servant or King? Constructing Balthazar

This study for Balthazar helped Peter Paul Rubens refine the figure of the king for a large painting of The Adoration of the Magi, commissioned by the town council of Antwerp, in Flanders (northern Belgium). The biblical story of three kings traveling from afar with gifts for the Christ child resonated in Catholic Antwerp, Rubens’s home city and a center of international commerce. The cult of the magi so captured the imagination of local inhabitants that many children were named Balthazar, Melchior, or Caspar after the kings. This oil sketch was painted on repurposed ledger paper; the marks of mercantile transactions are visible through the figure’s robe, face, and turban.

The immediacy and vibrancy of Rubens’s figure, with his parted mouth and gaze directed to the side, suggest an individual captured in a moment of speech and motion. Was this depiction inspired by an actual person, and if so, whom?

Rubens often drew from life (a practice used by other artists, including Andrea Mantegna, whose Adoration of the Magi was featured in the exhibition together with the oil study). One of Rubens’s patrons in Antwerp had Black African servants in his household, and Rubens made other studies using them as models. The Flemish city of Antwerp was a major center for the slave trade. Much research remains to be done on the status of forcibly Christianized Black Africans living there, specifically their positions and rights within domestic settings.

We also know that Rubens used an earlier print of Mulay Ahmad, the Hafsid Muslim ruler of Tunis, as inspiration for other works, such as The Three Magi Reunited. The Tunisian turban in Rubens’s head study casts the biblical character of Balthazar as a sixteenth-century North African king.

Thus Rubens’s Balthazar may be an amalgam of an unidentified sitter, likely a servant or enslaved person, and a nearly contemporary ruler. The artist’s image speaks to the intersections of power, faith, and race in commercial Antwerp at the height of its global reach.

African Europeans in the Courts of Europe

Europeans came to know African people in many different ways. While rulers made their way into the imagination of European artists, Africans living in Europe also became part of the art being produced at the time.

A significant number of Africans or members of the African diaspora in Europe occupied positions in the courts or noble households. Little documented, their histories can be guessed at from the evidence in archival documents and in art. Portrait of an African Man was long speculated to have been a painting of Christophle le More, a Black man, formerly a slave and groom, who went on to become an archer for the bodyguard of Emperor Charles V.

This painting by Jan Jansz Mostaert has long been celebrated as the only surviving European portrait of a Black man during this early period. Unlike images of Balthazar or other biblical figures, he wears the attire of a Flemish courtier. Moreover, he does not appear as a member of an entourage, but in the context of an individualized portrait. Who was this man?

Unlike the institution of slavery that became codified in the Americas at the time, it was possible for enslaved people in Europe to gain their freedom and to possess social mobility, working in positions as disparate as the elite bodyguard of the Holy Roman Emperor or as gondaliers in Venice.

Recent research has discouraged the identification of this sitter with Christophle, which leaves us only with the frustrating hints provided by his costume, such as the pilgrimage badge in his cap (to Our Lady of Halle, near Brussels), his gloves appropriate for a court setting, or for the embroidered bag at his waist, perhaps a gift from a wealthy patron.

Although his identity is unknown, he nevertheless offers a potent reminder of the lived experiences of Africans in medieval and Renaissance Europe.

This essay first appeared in the iris (CC BY 4.0)

Additional resources

Read Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe (PDF).

Introduction to gender in renaissance Italy

Ideal representatives of masculinity and femininity

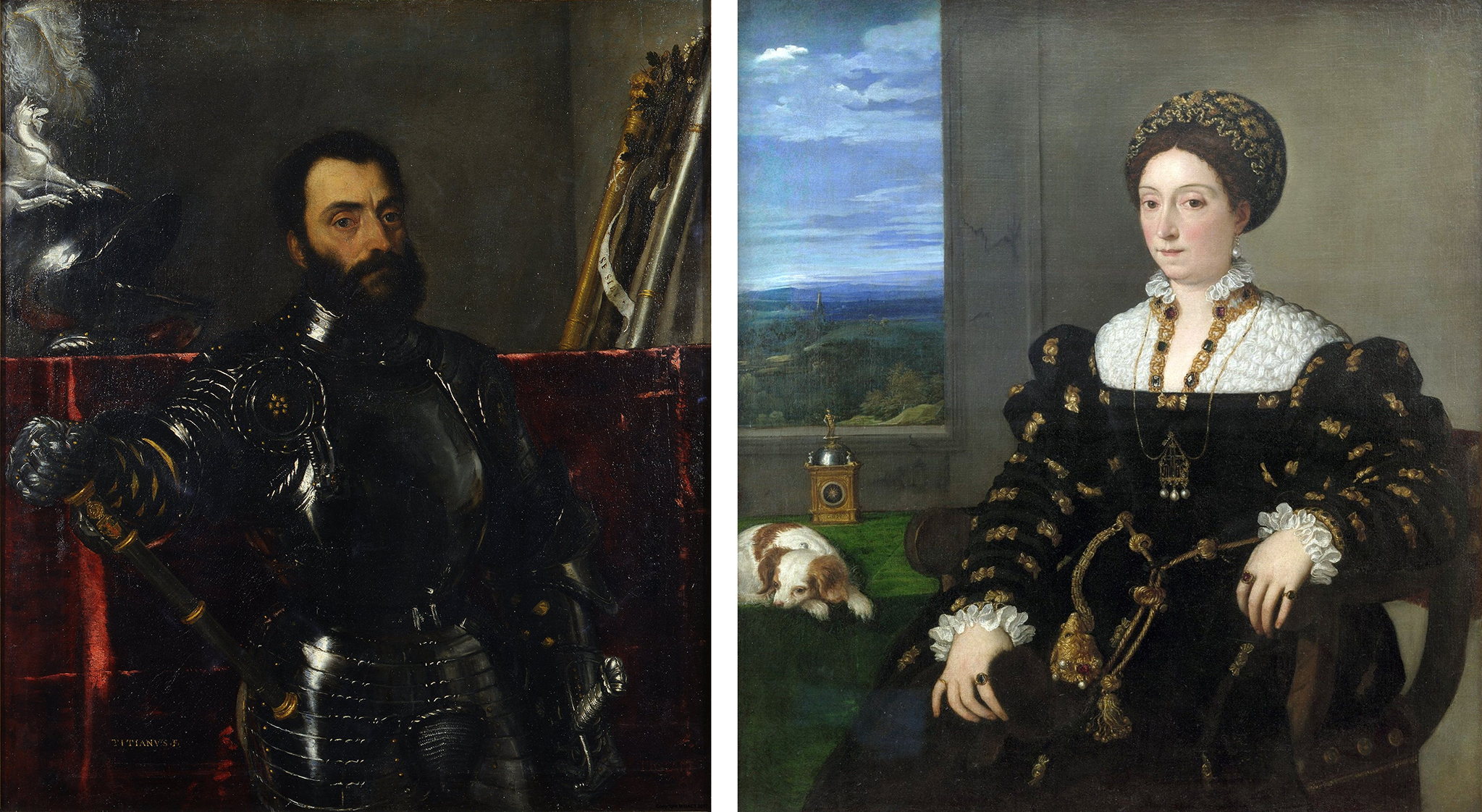

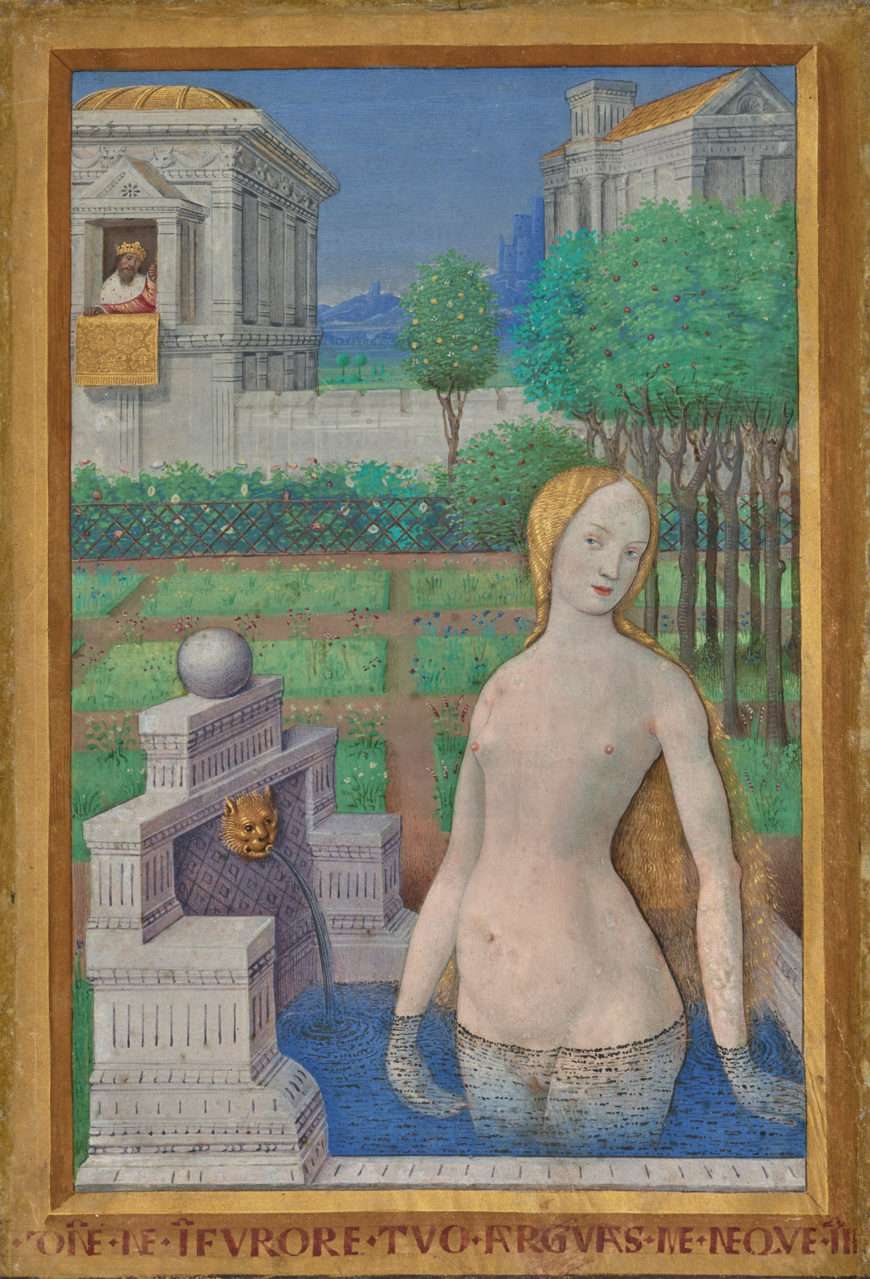

In a pair of portraits painted by the Venetian artist Titian, the Duke and Duchess of Urbino are presented as ideal representatives of their sexes. Duke Francesco Maria della Rovere, the great mercenary captain, stands upright, his body encased in shining armor. His right arm juts outward from his body, seemingly breaking through the picture plane, as his hand rests upon the war baton he carries as a reminder of his military authority as commander of Venetian troops. Francesco Maria’s prominent codpiece and piercing stare emphasize his aggressive masculinity, while his dark beard and ruddy complexion mark him as a mature man of action. The objects behind him communicate his valor and political commitments: two other war batons bearing the Papal Keys and the Florentine lily lean against a wall (the lily has faded over time) next to an oak branch marking his della Rovere lineage (the della Roveres were a powerful noble family of Italy).

His wife, the Duchess Eleonora Gonzaga, makes the perfect, demure counterpoint to her virile husband. While he stands erect and linear, she sits, swathed in copious folds of costly fabric that suggest the rounded forms of her body. While he is active, she is passive, her containment within the domestic sphere affirmed by the window to her right. Eleonora’s bodily comportment is a far remove from her husband’s thrusting fist that intrudes upon the audience’s space. The small dog and the costly clock that rests upon the table beside her remind us of her loyalty and patience in reservedly awaiting her husband whose military pursuits often kept him abroad.

Internal virtues, including gender characteristics, were believed to be communicated through outward appearance. The author Pietro Aretino noted in sonnets dedicated to Titian’s portraits that Francesco Maria’s “place between his eyebrows inspires terror, his spirit in his eyes, his pride in his forehead, in which place honor and wise counsel sit. In his armored chest and ready arm valor burns….” For Eleonora, “Prudence guards her honor and counsels in beautiful silence: the internal virtues adorn her brow with every wonder.” [1] Like the portraits, Aretino’s sonnets highlight Francesco Maria’s active and awe-inspiring masculinity and Eleanora’s passive feminine charms.

Titian’s portraits help us to understand ideas that people in the past had about gender. While sex is determined by biological markers such as genitalia and other genetic differences between male or female, gender refers to the social role that a person plays based upon individual and collective ideas about identity as it relates to being a man or a woman. Different cultures define masculinity and femininity differently. These social roles are constructed by multiple factors including medical understandings of the body and mind, as well as cultural and religious ideas about the sexes.

The feminine ideal

Have you seen that [Virgin] Annunciation that is in the cathedral, at the altar of Sant’ Ansano, next to the sacristy?…She seems to me to strike the most beautiful attitude, the most reverent and modest imaginable. Notice that she does not look at the angel but is almost frightened. She knew that it was an angel…What would she have done had it been a man! Take this as an example you maidens!—Bernardino de Siena [2]

When the popular fifteenth-century preacher, Bernardino da Siena, wanted to impress upon his female listeners the importance of proper feminine behavior, he pointed them to the model of the Virgin Mary as painted by the Sienese artist, Simone Martini. At the moment the archangel Gabriel announces to Mary that she would bear the son of God, Mary’s reaction is exemplary: she pulls her cloak tightly around her and recoils from the angelic intrusion in her private space. So important in this patriarchal world was the regulation of women to the domestic sphere, that even an emissary of God should be considered with caution. A renaissance woman’s primary virtues were chastity and motherhood; her domain was the private world of the home. As noted by the scholar and artistic theorist Leon Battista Alberti in his treatise On the Family (1435), “It would hardly win us respect if our wife busied herself among the men in the marketplace, out in the public eye.” [3]

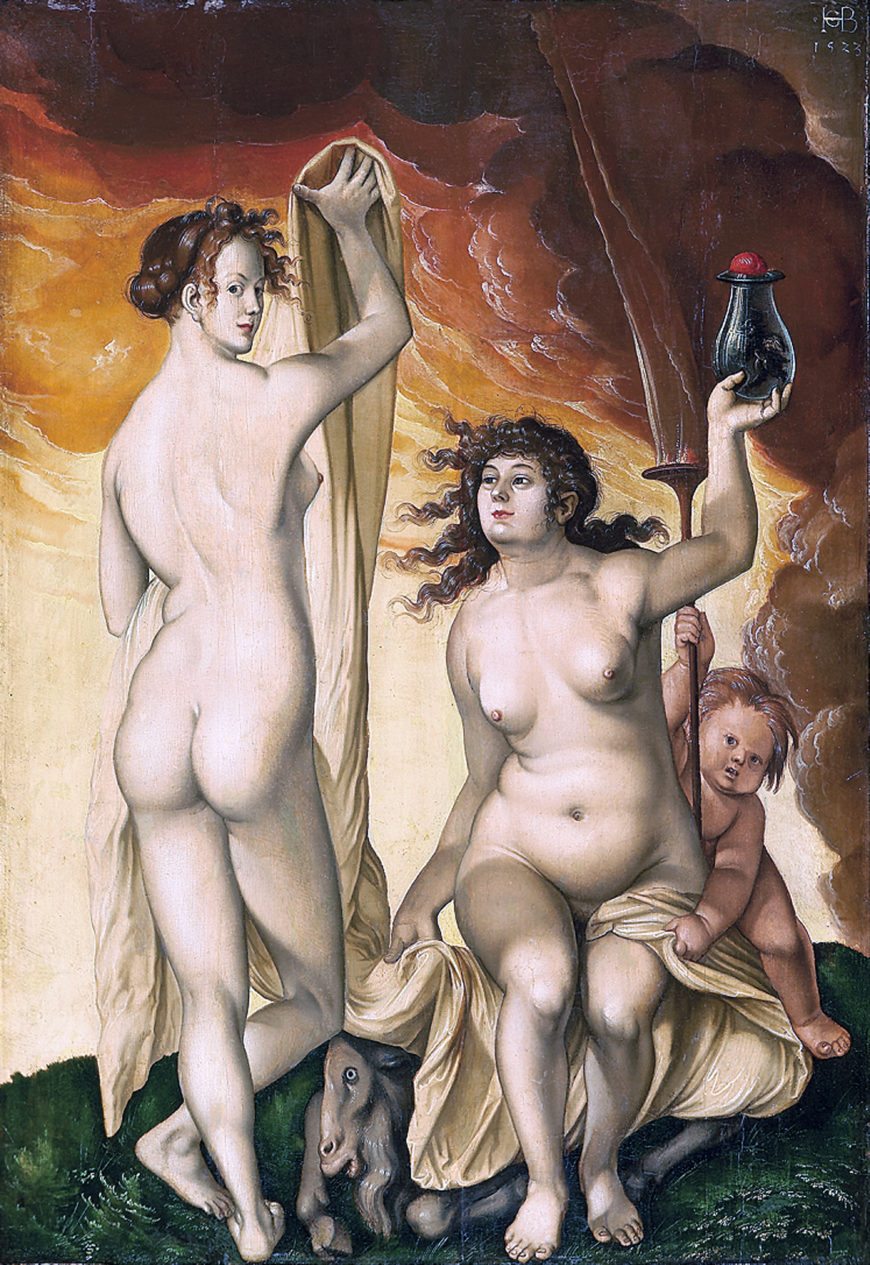

While gender roles were nuanced across European cultures, throughout the continent women’s relegation to the domestic sphere was rooted in Christian tradition that placed blame for humanity’s fall from grace upon Eve, the first woman. Eve was the temptress who led the first man, Adam, into breaking God’s law, sentencing humankind to toil and death. Every woman thereafter was thought to live in the shadow of Eve’s sin, justly sentenced to the pains of childbirth, the labors of motherhood, and submission to her husband.

The four humors

Women’s subordinate role in renaissance culture was also tied to medical understanding of the human body inherited from ancient Greek and Roman traditions. Perhaps most influential was the ancient theory of the four humors. Originating in ancient Greece, humoral theory was thoroughly developed by the Roman doctor, Galen, whose writings were important to the medieval and renaissance world. According to Galen, it was the proper balance of four fluids called humors—blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile—generated through the processes of digestion that determined physical and psychological health. Each humor was associated with particular mental characteristics, making a person’s psychobiology a product of his or her unique humoral composition, a model further nuanced by qualities of temperature and moisture also assigned to the various humors.

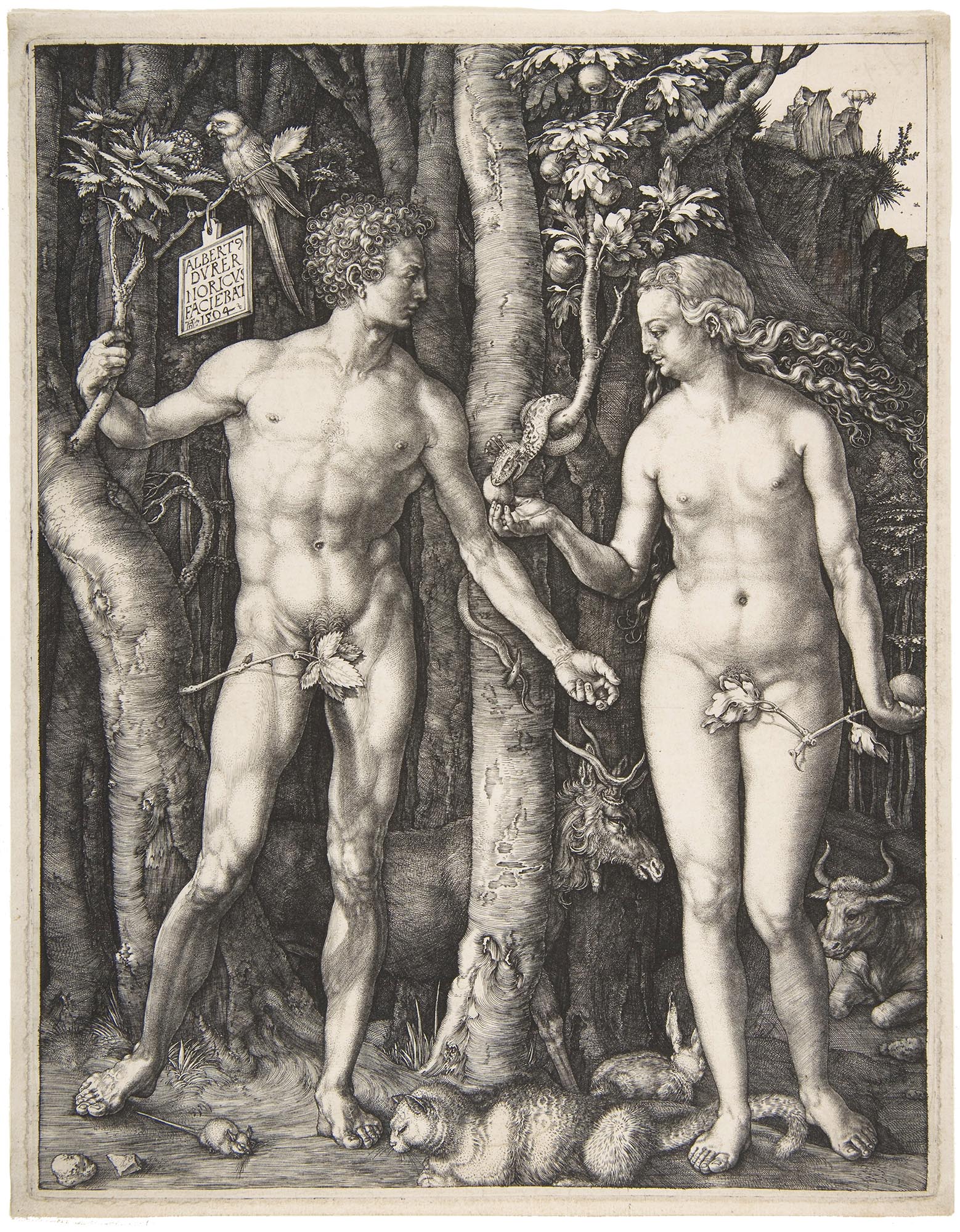

German artist Albrecht Dürer’s engraving of Adam and Eve includes numerous symbols associated with the four humors: a rabbit (blood), an ox (phlegm), a cat (yellow bile), and an elk (black bile). This image captures the moment just before the first man and woman broke God’s law. All of the animals—all of the humors—are shown at rest, symbolizing humanity’s perfect internal balance before the Fall from Grace.

Generally speaking, men and women were understood to be humoral opposites. Men were physiologically characterized by superior humors associated with heat and dryness, women by inferior humors associated with cold and wetness. These perceived differences were used to justify men’s and women’s social roles: a man’s hot-dryness gave him the constancy necessary for public social and political life; a women’s cold-wetness made her inconstant, accounted for her timidity, and explained menstruation and the pains of childbirth. As Alberti also noted in his writings on the family, “Women are almost all timid by nature, soft, slow, and therefore more useful when they sit still and watch over things.” [4]

Women’s assumed physiological inferiority to men also contributed to how they were thought to experience emotions. Women’s cold-wet humoral nature made them more susceptible to emotions and less capable of managing their emotional behaviors in socially appropriate ways. In works of art like Guido Mazzoni’s terracotta Lamentation tableau created for the Duke of Ferrara, biblical characters perform their sorrow over Christ’s death in ways that reflect expectations for gendered emotional experience: the women are collectively far more violent than the men in their expressions of grief.

Titian’s composed and contained Duchess Eleonora perfectly reflects the gendered ideal for a renaissance woman. Her youthful beauty, her curvaceous form suggesting the fertility of motherhood, and her careful containment within the domestic realm all communicate renaissance expectations of and ideals for femininity. It is rare in renaissance art to encounter women whose features do not reflect standards of youthful beauty and the relationship to women’s primarily maternal role that they embody.

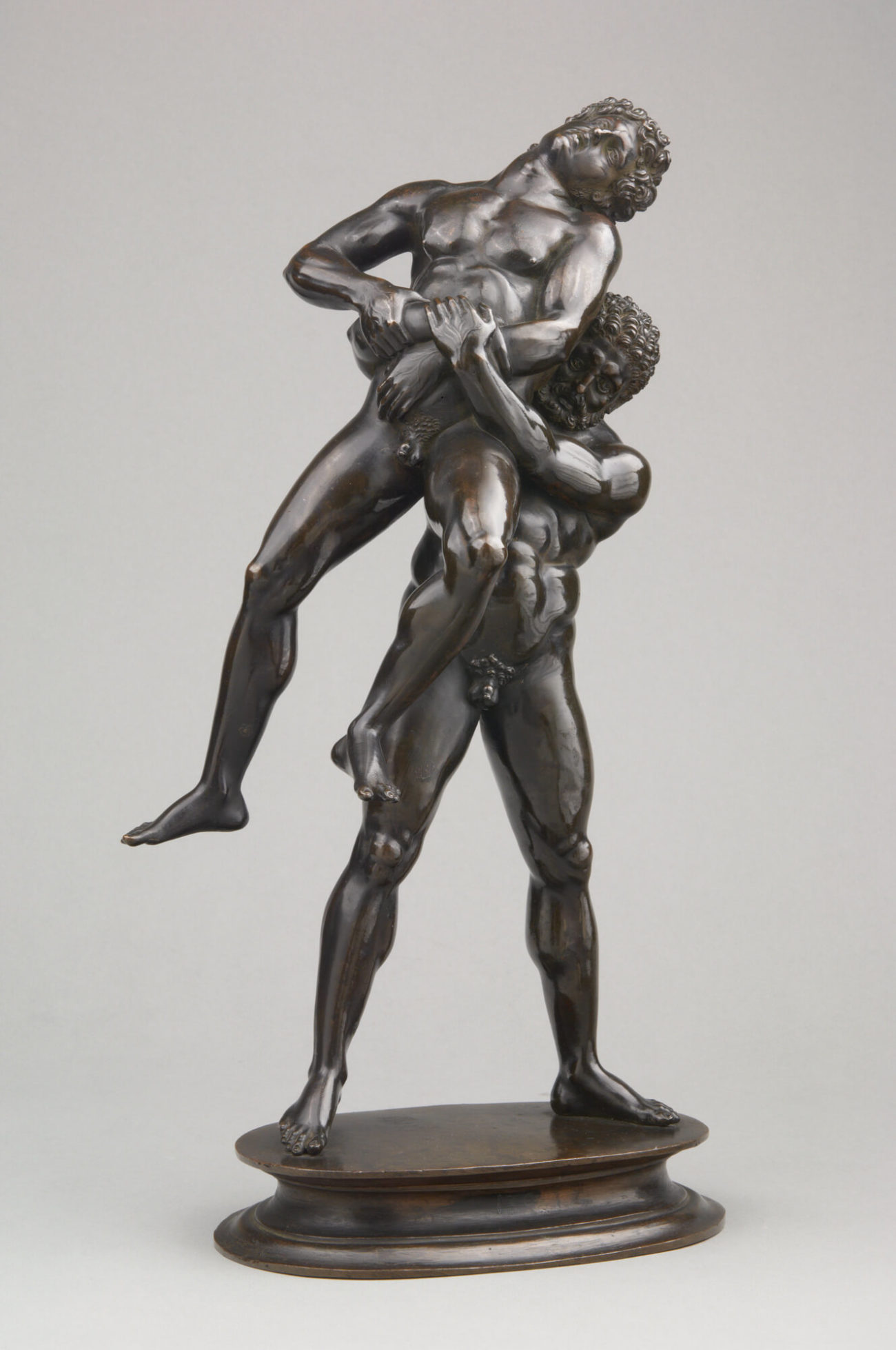

The masculine ideal

Fortune is a woman and if you wish to keep her under it is necessary to beat and ill use her; and it is seen she allows herself to be mastered by the adventurous rather than by those who go to work more coldly. She is, therefore, always woman-like, a lover of young men, because they are less cautious, more violent, and with more audacity to command her.

Machiavelli, The Prince [5]