5.1: History, Beliefs, Rituals, Legends

- Page ID

- 236850

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

The Anishinaabe

The Ojibwe, also known as Chippewa, refer to themselves in their original language as the Anishinaabe, or “the people.” The term Ojibwe comes from what other tribes called the Anishinaabe people, and means “puckered”, which refers to the toes of the moccasins that the Anishinaabe people made and wore. The term Chippewa is just a variation of the pronunciation of the word Ojibwe.

Numbering more than more than 170,000 in the United States and more than 160,00 in Canada, the Ojibwe people are a network of independent bands or tribes, knit together by a shared language, culture, and traditional clan system, and inhabiting the Western Great Lakes region of Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, North Dakota, Ontario, and Manitoba. The Anishinaabe are culturally related to other peoples of the Northeast Woodlands and linguistically related to other peoples of the Algonkian language family.[1]

History and Belief

According to oral history, the people who eventually became known as the Anishinaabe originated on the east coast of North America, and because of a series of prophecies, they traveled by various routes to the western Great Lakes area, both north and south of the lakes. These prophecies came to be known as the Seven Fires. The Seven Fires Prophecies make for vivid and interesting listening: Seven Fires Prophecies

The religious beliefs and activities of the Anishinaabe can vary from place to place, and clan to clan, but are all based on a profound respect for life and the gifts of life.

Beliefs include:

- understanding the manidoog (sometimes spelled manitous), the spirits, or “mysteries.” The manidoog are the sources of life and existence. All things have spirit–plants, animals, the earth, as well as people.

- gratitude to the Giche Manidoo, “Great Spirit” or “Great Mystery.” The Anishinaabe are basically monotheistic, although some also refer to Mother Earth as worthy of reverence. Mother Earth is considered both the physical manifestation of all physical creation, and also of the Great Spirit Gitche Manidoo who created it.

- praying to the spirits is important, asking for health, expressing gratitude, looking for assistance in troubles, rejoicing, naming children, and much more. Prayer takes many forms, but is often accompanied by one or more of these– smoke, drums, singing and dance.

- Elders are respected for their wisdom and knowledge. The clan system revers these wise ones, and various behaviors indicating respect are part of daily life.

- Women are respected as bearers of life, and protectors of water.

- A key value includes walking in harmony with the world, connected to all parts of the land, with no separation between sacred and secular.

As with many indigenous peoples, the immigrant Europeans tried to impose their lifestyle, beliefs, and manners on the tribes of the Americas. With the Ojibwe, this took the form of removing them from their land, forcing them into individual land ownership and farming instead of communal land ownership and hunting/gardening, and various forms of forced assimilation. For decades Ojibwe children were removed from their homes and send to “boarding schools” in order to lose their native identities, languages and practices. Learning about these schools, and the graveyards now being discovered across Canada and the US is crucial to understanding some of the suffering still being experienced in Ojibwe culture.

A story: Catholic Boarding School in Wisconsin

One woman’s story of her mother’s experience in a school, and the impact on her life, the life of her children, and her legacy. The Atlantic is a subscription publication, but allows for a few free articles a month.

Death by Civilization: the traumatic legacy of native boarding schools

The tribe local to the the author’s home is the Fond du Lac Band of Ojibwe, and is primarily located in Cloquet, Minnesota. Before white settlers arrived here, the band lived in an area in Duluth now key to commercial shipping, and with access to both the large natural harbor and to Lake Superior, called Gichigami. More in depth stories about the lives and history of the people who originally lived at this western end of Lake Superior can be found here: Onigamiinising Dibaajimowinan

The Fond du Lac Band is one of six Chippewa Indian Bands that make up the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe. The Fond du Lac Reservation was established by the La Pointe Treaty of 1854. Archaeologists, however, maintain that ancestors of the present day Chippewa (Ojibwe) have resided in the Great Lakes area since 800 A.D. Today, our Band includes over 4,200 members. The Ojibwe name for the Fond du Lac Reservation is “Nagaajiwanaang”, which means “where the water stops”.[2]

Local life of the Anishinaabe is seen in many places around the city, including at American Indian Community Housing Organization, at art galleries in the area, both at the University of Minnesota and at the AICHO Galleries, in the Lake Superior Ojibwe Gallery, and in many public parks, as increasingly the debt owed to the Anishinaabe is becoming clearer. Local colleges offer language and history courses, and local authors bring materials to local readers. Onigamiising is a set of essays on life in Duluth as an Ojibwe.

Lyz Jaakola is an Ojibwe member of the Fond du Lac Band and well known musician in the area. Hear her comments on the ongoing struggle for health in the community, and her composition for healing.

Healing Music: Lyz Jaakola

Location

Whether one accepts the oral tradition of the Seven Fires or not, both Ojibwe oral history and a number of archaeological finds indicate that these people moved from the east coast to the upper midwest over several centuries. It is well documented that by the time the French fur traders and various explorers arrived in the Great Lakes area in the early 1600s, the Ojibwe were well established as far west as Sault Ste. Marie, Madeleine Island at the northern tip of Wisconsin, and into Minnesota.

One of the larger tribes in North America, the Ojibwe live in both the United States and Canada and occupy land primarily around the western Great Lakes, tribes being located in Minnesota, North Dakota, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Ontario. The Ojibwe tribes who moved into the plains area of North Dakota and north into Canada are known as the Saulteaux.

Lifestyle

The Ojibwe have historically lived in heavily forested areas, rich with lakes, rivers, and swamps. Activities in their originally semi-nomadic lives have included:

- hunting, usually for bear, deer, moose and various birds

- fishing, by spear, hook, and in all seasons, including ice fishing in the winter

- maple sugar and syrup production

- harvesting wild rice, the “food that grows on water”, which was prophesied for them long before their arrival in the Great Lakes area

- gathering, but also some gardening

These activities continue in modern life, with increasing attention being paid to former treaties that guarantee that these activities may continue on tribal lands.

Example–Wild ricing in northern Minnesota

Manoominikewag

Ritual

Various rituals relating to spirituality have developed over the centuries among the Anishinaabe. These may include:

- smudging–usually using one of 4 herbs–tobacco, sage, cedar and sweetgrass-smoke is created to surround and cover a place, a person, a thing, or a situation for purity, cleansing, hope

- sweat lodges–small constructions with heated rocks to are constructed and used by people in a way that causes deep sweats. Adding to this prayers and ritual on the interior provides healing, direction, or other ways of connecting with the spirit

- vision quests–a time of fasting and solitude arranged so that young people might find their purpose, direction

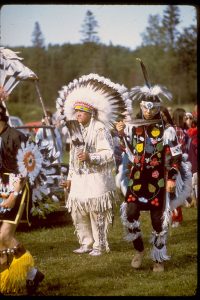

- pow-wows–held for many reasons, these times of dance, eating, and ceremony are a community event for rejoicing, naming of children, supporting sobriety, community health

- drumming circles–the drums speak through the drummers. The drummers allow the voice of the spirit to come to the people through the drums

- sacred pipes–not Peace Pipes, which is a European phrase, but a carefully held and prepared pipe is used for prayer; as the smoke rises , so do the prayers

- Midewiwin (Medicine Lodge)–composed of healers and spiritual leaders, this is a fairly guarded set of knowledge that allows those trained in this knowledge to support the community in body and soul

- gift exchanges–connecting with community through giving

- clan identity–there are up to 29 acknowledged clans within the Anishinaabe people: a little more information can be found here

About the Clans

And, of course, there are many narratives, stories, shared detail from the elders of the community.

The Anishinaabe Creation story

“White Earth Wild Rice Harvest- Manoominikewag.” White Earth Land Recovery Project, 14 Sept. 2013, youtu.be/Zs8UyGlL3iU.

“The Ojibwe People.” Minnesota Historical Society, 2021, www.mnhs.org/fortsnelling/learn/native-americans/ojibwe-people.

“‘Strong Woman’s Song’ by Lyz Jaakola.” YouTube, 20 Oct. 2020, youtu.be/g7zRxLCd9Lk.

Fond Du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, 2021, www.fdlrez.com/.

Pember, Mary Annette. “Death by Civilization.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 8 Mar. 2019, www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2019/03/traumatic-legacy-indian-boarding-schools/584293/.

“The Ojibway Creation Story: Fire and Water: Ojibway Teachings and Today’s Duties.’” Ojibwe Creation Stories, University of Toronto Libraries, 2021, exhibits.library.utoronto.ca/items/show/2505.

“Anishinaabe Ojibwe Ways.” The Pluralism Project, Harvard University, 2021, pluralism.org/anishinaabe-ojibwe-ways.

“Anishinaabe (NA): The Ojibwe PEOPLE’S DICTIONARY.” Anishinaabe (Na) | The Ojibwe People’s Dictionary, University of Minnesota, 2021, ojibwe.lib.umn.edu/main-entry/anishinaabe-na.

“Anishinaabe Timeline.” American Indian Resource Center, Bemidji State University, 2021, www.bemidjistate.edu/airc/community-resources/anishinaabe-timeline/.

White Earth Nation, 2021, whiteearth.com/.

Peacock, Thomas D., and Marlene Wisuri. Ojibwe WAASA Inaabidaa = We Look in All Directions. Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2011.

- with help from The Pluralism Project: Harvard University https://pluralism.org/anishinaabe-ojibwe-ways ↵