1.2: Sacred Texts

- Page ID

- 236834

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

Start by reading this article from the New York Times: What is the Meaning of Sacred Texts? https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/11/b...armstrong.html

Karen Armstrong, author and former nun, writes, “Our English word ‘Scripture’ implies a written text, but most Scriptures began as texts that were composed and transmitted orally,” she writes. “Indeed, in some traditions, the sound of the inspired words would always be more important than their semantic meaning. Scripture was usually sung, chanted or declaimed in a way that separated it from mundane speech, so that words — a product of the brain’s left hemisphere — were fused with the more indefinable emotions of the right.”

The author of the article regarding Armstrong’s book about scriptures, Nicholas Kristoff, says,

“Armstrong argues that this approach [literal reading] misunderstands how Scripture works. It’s like complaining about Shakespeare bending history, or protesting that a great song isn’t factual. That resonates. Anyone who has been to a Catholic Mass or a Pentecostal service, or experienced the recitation of the Quran or a Tibetan Buddhist chant, knows that they couldn’t fully be captured by a transcript any more than a song can be by its lyrics. “

Armstrong states, in a way that helps the reader understand the difference between something being insightful and something being factual,

“Because it does not conform to modern scientific and historical norms, many people dismiss Scripture as incredible and patently ‘untrue,’ but they do not apply the same criteria to a novel, which yields profound and valuable insights by means of fiction,”

Armstrong writes:

“A work of art, be it a novel, a poem, or a Scripture, must be read according to the laws of its genre.”

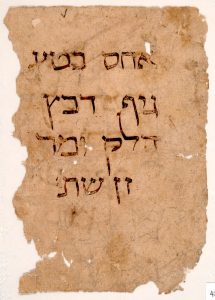

Many faiths have a rich history of revered and honored texts, be they the word of God as revealed to prophets, oral stories retold by one generation to another over centuries, or the sayings of a Teacher written down (eventually) into books. Looking at the history and context of these writings is useful as one explores the origins and developments of the world’s major faiths. It is also important to understand that a number of religious expressions have used and continue to use oral tradition in passing on teachings, rituals, stories and rules. In some places, oral tradition has never been and possibly never will be written down in any formal way. In some other places what is written down for a culture or group or tribe may come after centuries of oral expression, passing on stories, ideas, rituals and other values. And all writing must be set into its context–when was it written, for whom was it written, why was it written, what function did it serve? All of these questions help us understand the role of any sacred text.

Read a bit of good basic information about sacred texts and their development, style, and content here at Britannica: Scripture: Religious Literature (https://www.britannica.com/topic/scripture . In this you will find:

- A broad definition

- Characteristics of sacred writings

- How western or non-western writings differ

The use of sacred texts helps make tangible the beliefs and history of a faith tradition. This can be useful in approaching any particular faith. It can also, in some ways, freeze a faith tradition in time. Cultural, historic, and geographic context matters, as one considers what has gone into making a text what it is. Reading any text as if it were written today is to miss both the real meaning, but also to miss the possible richness found in its words and images and stories. In most faith traditions, the interpretation of the written word matters a great deal, and years of study is needed in order to help understand what is involved in something that seems, at first, to be simple.

Let’s use an example of how this interpretation might work. We will look at a portion of writing from the Hebrew prophet Isaiah. Isaiah lived in 8th century BCE. He was a prophet after whom the book of Isaiah is named. His call to prophecy in mid-8th century BCE coincided with the beginnings of the expansion of the Assyrian empire, which was just to the east of Israel, and which threatened Israel. Isaiah proclaimed, in poetry, prose and story, and certainly in this following parable, warnings from Yahweh to the people of Israel, whom he claimed were abandoning their faith and ethics. We are going to look at a story from the prophet Isaiah, chapter 5, verses 1-7.

If you do not know the agricultural importance of a vineyard to the people of Israel, nor what work goes into cultivating vines, then a story about a failed vineyard is a little hard to follow. What’s the fuss here, and why is the owner of the vineyard complaining? But if one starts to understand that parts of the country of Israel are arid, and only small numbers and types of crops thrive in some of those places, one starts to have a little more context. And then when the total disappointment of a failed crop clearly means that the owner has no income, that this is a true catastrophe, then we have even more context.

Still, this narrative is not just a story of a failed grape crop. This story is making a point to the reader. We must realize that this is no ordinary vineyard owner, but is Yahweh, the God of Israel. And these are not really vines, but are instead the people of Israel who are producing “sour grapes”, unfit for eating or for making wine. Then when we look at when this story is written, we see that the people of Israel at this time are trying to become a nation like any other surrounding them, and as a people they are not following the basic commandments of their faith, nor following Yahweh as commanded in the covenant that they have with their God.

Surrounding nations are taking notice that Israel has some decent water resources, has access to the ocean and ports, and that it is a prime crossroads for trade routes. The people of Israel are not faithful to their religious origins, however, and the guidance and protection of Yahweh seems to mean little to them any more–ambition and power are seeming to be more attractive to the people at the time of this prophet. So Yahweh, seen in the story as the owner of this poorly producing vineyard, is going to allow the vines–those people– to reap the consequences of their current behavior and see how they like those consequences. Yahweh symbolically throws hands in the air and lets the surrounding nations deliver those consequences, once the protection of Yahweh is gone. One can, with a bit more historic and cultural context, then, read the parable of the Vineyard owner in the Hebrew prophet Isaiah, chapter 5: 1-7

The Song of the Unfruitful Vineyard (NRSV)

5 Let me sing for my beloved my love-song concerning his vineyard:

My beloved had a vineyard

on a very fertile hill.

2 He dug it and cleared it of stones,

and planted it with choice vines;

he built a watchtower in the midst of it,

and hewed out a wine vat in it;

he expected it to yield grapes,

but it yielded wild grapes.

3 And now, inhabitants of Jerusalem

and people of Judah,

judge between me

and my vineyard.

4 What more was there to do for my vineyard

that I have not done in it?

When I expected it to yield grapes,

why did it yield wild grapes?

5 And now I will tell you

what I will do to my vineyard.

I will remove its hedge,

and it shall be devoured;

I will break down its wall,

and it shall be trampled down.

6 I will make it a waste;

it shall not be pruned or hoed,

and it shall be overgrown with briers and thorns;

I will also command the clouds

that they rain no rain upon it.

7 For the vineyard of the Lord of hosts

is the house of Israel,

and the people of Judah

are his pleasant planting;

he expected justice,

but saw bloodshed;

righteousness,

but heard a cry!

Analysis

When a reader starts to approach a Sacred Text, is is important that they do a little research. The reader should always ask:

- Who wrote this? (was it a priest? a scholar? a storyteller? a prophet?)

- When was it written? (can you find a reliable date?)

- Where was this written? (location, location, location matters)

- Who was the audience? ( common people? religious leaders?)

- What form does this take? (Sayings? story? poetry? instructions?)

When the reader knows a bit more about the who, what, where, when and why of any Sacred Text, then the material can being to sing.

Take a look at the Sacred Texts website for the British Library. In it are articles, videos, data and reflection from experts in the fields of sacred writings. British Library: Sacred Texts

- First, note the various traditions being considered in the site

- Second, be aware that there are more traditions not considered here then there are present for study.

- Third, look for other sites that may have resources available. One such, which just offers the texts with no commentary, is Internet Sacred Text Archive

There are many, many texts found in the religions of the world, some of which will seem familiar, and some of which you may never have heard.

They are a fascinating mix of advice, historical style writings, rules, mythology, ritual, guidance and encouragement. Each unit in the text will have links to original writings for that faith tradition, translated into English. Almost none of the sacred texts in the world were written in English, however, so one must be aware that there are nuances not found in the translation!

“You are what you believe in. You become that which you believe you can become”

―“If you realize that all things change, there is nothing you will try to hold on to. If you are not afraid of dying, there is nothing you cannot achieve.”

―“Whoever destroys a single life is as guilty as though he had destroyed the entire world and whoever rescues a single life earns as much merit as though he had rescued the entire world.”

–Mishnah Sanhedrin 4:5; Yerushalmi Talmud 4:9“He who knows and knows that he knows is a wise man – follow him; he who knows not and knows not that he knows not is a fool – shun him”

―

Sacred Texts in so many traditions were created as something resembling what we would call fiction. They are written as literature, meant to educate, elevate, inspire and support us, but not to give us rigid interpretations of preconceived views nor absolutely accurate historical narrative, and so reading them thus is a mistake.

Example: A Mission

Reading Sacred Texts is tricky. Check some advice on how this is being done in modern times! Read about the impact that early Mesopotamian culture had on Jewish, Christian and Muslim writings, and how it makes clear that scriptures change with time and culture and human interpretation. “An especially gifted scribe would sometimes be required to address current preoccupations by transforming and adapting the ancient traditions. He was even allowed to insert new material into the stories and Wisdom literature of the past. This introduces us to an important theme in the history of scripture. Today we tend to regard a scriptural canon as irrevocably closed and its texts sacrosanct, but we shall find that in all cultures, scripture was essentially a work in progress, constantly changing to meet new conditions. This was certainly the case in ancient Mesopotamia. An exceptionally advanced scribe was allowed—indeed expected—to improvise, and this enabled Mesopotamian culture to survive the demise of the original Sumerian dynasties and inform the later Akkadian and Babylonian regimes by grafting the new onto the old.”

It is a mistake that people make fairly regularly, however, and this style of reading sacred texts allows the literalist to condemn or attack others for not reading and accepting these sacred words in the same way that they, as literalists, choose to interpret them. Fundamentalists in various religions can cite passages from the Apostle Paul to oppose same-sex marriage or the ordination of women, they can quote the Torah to displace Palestinians from land in Israel, or they can point to narrow, out of context passages in the Quran to justify violence against those that they want to attack for other reasons — but all of that behavior and reading is an abuse and misuse of those Sacred Texts, and does not reflect the role that they have always been intended to play. We must know the genre, the original audience, the writer, and the intent of these writings in order to gain the wisdom that they have on offer for all readers. This is true whether those readers are believers or whether the readers approach the texts purely as interested students of this material.

“Discovering Sacred Texts.” The British Library, The British Library, 27 May 2015,

www.bl.uk/sacred-texts.

Internet Sacred Text Archive Home, www.sacred-texts.com/.

“Scripture.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., www.britannica.com/topic/scripture.

Kristof, Nicholas. “What Is the Meaning of Sacred Texts?” The New York Times, The New York Times, 11 Nov. 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/11/11/books/review/the-lost-art-of-scripture-karen-armstrong.html.

Armstrong, Karen. The Lost Art of Scripture: Rescuing the Sacred Texts. Anchor Books, 2020.

Bhagavad Gita Free PDF – University of Macau. Translated by Lars Martin Fosse, University of Macau, library.um.edu.mo/ebooks/b17771201.pdf.

The Analects of Confucius. Translated by Robert Eno, University of Indiana, chinatxt.sitehost.iu.edu/Analects_of_Confucius_(Eno-2015).pdf.

“Dao De Jing (Eno) – Indiana University Early Chinese Thought[B\/E\/P374 Fall 2010(R Eno The Dao De Jing Introduction If You Walk into Borders Books or: Course Hero.” Translated by Robert Eno, Dao De Jing (Eno) – Indiana University Early Chinese Thought[B\/E\/P374 Fall 2010(R Eno The Dao De Jing Introduction

New Revised Standard Version (NRSV)New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright © 1989 the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Clayson, Jane, and Anna Bauman. “A Mission To Reinterpret The World’s Sacred Texts.” A Mission To Reinterpret The World’s Sacred Texts | On Point, WBUR, 4 Dec. 2019, www.wbur.org/onpoint/2019/12/04/karen-armstrong-lost-art-scripture.