6.8: Prewriting Strategies

- Page ID

- 58325

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Describe and use prewriting strategies (such as journaling, mapping, questioning, sketching)

Prewriting has no set structure or organization; it is usually just a collection of ideas that may find themselves in your paper over time. Prewriting is also a great way to get past writer’s block—that period of time when you find you have no ideas or don’t know how to put your thoughts together. There is no right or wrong way to approach prewriting, but there are some strategies that can get you thinking. You already learned about brainstorming and freewriting, but there are other helpful techniques to get you started that include journaling, mapping, questioning, and sketching.

Journaling

Many people write in personal journals (or online blogs). Writers not only record events in journals, but also reflect and record thoughts, observations, questions, and feelings. They are safe spaces to record your experience of the world.

Use a journal to write about an experience you had, different reactions you have observed to the same situation, a current item in the news, an ethical problem at work, an incident with one of your children, a memorable childhood experience of your own, etc. Try to probe the why or how of the situation.

Journals can help you develop ideas for writing. When you review your journal entries, you may find that you keep coming back to a particular topic, or that you have written a lot about one topic in a specific entry, or that you’re really passionate about an issue. Those are the topics, then, about which you obviously have something to say. Those are the topics you might develop further in a piece of writing.

Here’s one sample journal entry. Read through it and look for ideas that the writer might develop further in a piece of writing:

The hot issue here has been rising gas prices. People in our town are mostly commuters who work in the state capitol and have to drive about 30 miles each way to and from work. One local gas station has been working with the gas company to establish a gas cooperative, where folks who joined would pay a bit less per gallon. I don’t know whether I like this idea – it’s like joining one of those stores where you have to pay to shop there. You’ve got to buy a lot to recoup your membership fee. I wonder if this is a ploy of the gas company???? Others were talking about starting a petition to the local commuter bus service, to add more routes and times, as the current service isn’t enough to address workers’ schedules and needs. Still others are talking about initiating a light rail system, but this is an alternative that will take a lot of years and won’t address the situation immediately. I remember the gas crunch a number of years ago and remember that we simply started to carpool. In the Washington, DC area, with its huge traffic problems and large number of commuters, carpooling is so accepted that there are designated parking and pickup places along the highway, and it’s apparently accepted for strangers to pull over, let those waiting know where they’re headed, and offer rides. I’m not certain I’d go that far . . .

Mapping Strategy

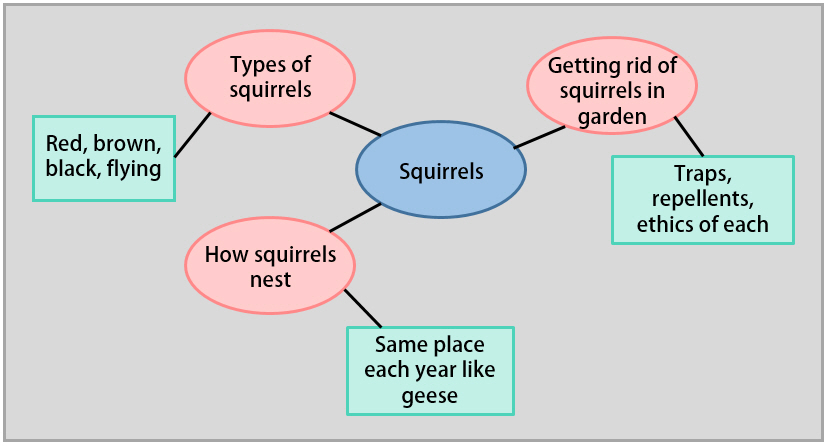

Mapping or diagramming is similar to freewriting, but the outcome often looks more like a list of related ideas. This strategy is quite similar to brainstorming where the listed ideas may or may not be connected with arrows or lines. You should set a time limit of 5 to 10 minutes and jot down all the ideas you have about the topic. Instead of writing sentences, you are quickly jotting down ideas, perhaps showing connections and building a map of your thoughts. Here are some online tools that can help with this process:

Mapping and diagramming may help you create information on a topic, and/or organize information from a list or freewriting entries, as a map provides a visual for the types of information you’ve generated about a topic. For example:

Questioning Strategy

This is a basic strategy, useful at many levels, that helps you jot down the basic important information about a topic. Starting by asking the questions who? what? when? where? why? and how? For example, below are answers created for the topic: What is the impact of traditional ecological knowledge on environmental management?

- Who? The Dene and Kissi tribes from two different ecosystems were impacted by European colonizers and their fire management policies.

- What? Consider the impact of fire on the peoples in both environments.

- Where? Canadian policies and historical data compared to African policies and historical data.

- When? As far back as the last ice age, there is evidence of how fire has impacted the land. I will focus on the impact of colonization and the policies that affected the land management practices of the indigenous peoples. I will also consider the current implications of controlling and preventing fires.

- Why? This information is important because the knowledge from the indigenous peoples and their traditional practices provides important insights into how to improve current fire practices.

- How? Look at historical and current records, such as Lewis, Wuerthner, Fairhead and Leach . . .

Notice how this series of questions and answers is more developed than this topic would be if you were thinking about it for the first time. This author has done a bit of preliminary reading on the subject between the two prewriting activities. This helps illustrate how prewriting can be useful to return to, even after later stages of the writing process.

If you have a broad topic you want to write about, but don’t quite know how to narrow it, you can also ask defining questions to help you develop your main idea for writing. For example, if you want to write about school taxes, you could ask:

- Why do only property owners (and not renters) in New York State pay school taxes?

- What percent of overall school funding comes from school taxes?

- Do other states fund schools in the same way?

- Does the state lottery system, initially designed to fund schools, actually support schools?

- Is there a limit to paying school taxes when one gets older and no longer has children in school?

Once you have your questions, you can work with the list to group related questions, and then decide whether your writing can logically deal with a number of the questions together or only one. Use questioning to help develop a focus for your writing.

Sketching Strategy

A picture is worth a thousand words. Your first thinking is done in pictures. So, if you are a visual learner and like to sketch out your thoughts, grab a pen and paper and draw what you are thinking. This strategy is especially effective if you are trying to conceptualize an idea or clarify relationships between parts of an idea.

Sketching involves drawing out your ideas using a pen and paper. One strategy that can be useful for planning comparison and contrast type papers is a Venn diagram. A Venn diagram is a strategy that uses two (or more) overlapping circles to show relationships between sets of ideas. The information written where two circles overlap is common to both ideas. The information written outside the overlapping area is information distinct to only one of the ideas.

Explore the sketch of a Venn diagram created for the topic: What is the impact of traditional ecological knowledge on environmental management?

Notice how this Venn Diagram is even more developed than the same topic explored previously. This author has done even deeper research on the subject, demonstrated by the citations given after some facts here. Again, this helps illustrate how prewriting can be useful to return to, even after later stages of the writing process.

Of course, this is not a comprehensive list of prewriting strategies. You may find that some of these are helpful for certain types of writing projects, or you may prefer other strategies such as making lists, bulleting key points, or writing out pros and cons. Whichever strategy you choose, be sure to save your prewriting work. You may want to revisit this stage of the writing process again to make sure that you captured all your thoughts in your outline or first draft. You may also want to do more prewriting in the middle of your writing project if you need some help overcoming writer’s block.

Contributors and Attributions

- Revision and Adaptation. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Mapping. Provided by: Excelsior OWL. Located at: https://owl.excelsior.edu/writing-process/prewriting-strategies/prewriting-strategies-mapping/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Prewriting. Provided by: Lethbridge College. Located at: www.lethbridgecollege.net/elearningcafe/index.php/writing/the-writing-process/prewriting. Project: eLearning Cafe. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Freewriting. Provided by: Excelsior OWL. Located at: https://owl.excelsior.edu/writing-process/prewriting-strategies/prewriting-strategies-freewriting/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Journaling. Provided by: Excelsior OWL. Located at: https://owl.excelsior.edu/writing-process/prewriting-strategies/prewriting-strategies-journaling/. License: CC BY: Attribution