8: Early Film Music

- Page ID

- 371196

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)What is Film Music?

Since it's likely that you are familiar with certain modern film scores, the focus of this module is understand how film music (as it exists now) came to be. As James Buhler's text on film music states: "Film Music is any music used in a film." (Buhler et al, 2010, p. 4) This includes everything from a newly written score, pre-existent music of any kind, music heard by the characters in a film, and music on the score which is not experienced by the characters.

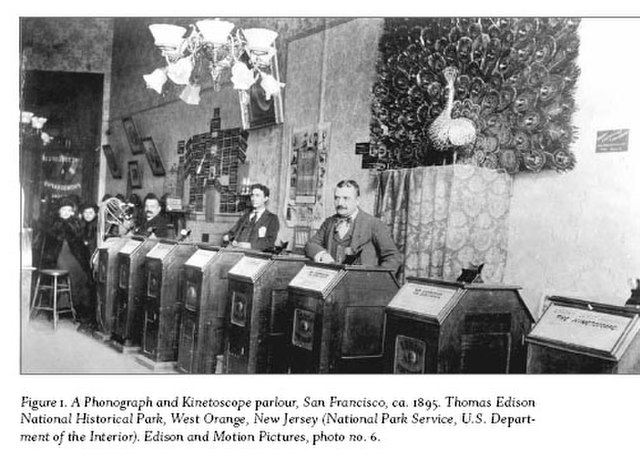

A useful place to start is with the development of film technology. In around 1894, inventor Thomas Edison unveiled a machine called the Kinetoscope, "a peephole viewer for a single person to observe moving pictures without sound." (Hickman 2016, 65) These were gathered into parlors where people would pay money to watch short films. You might have seen something like this on Main Street in Disneyland:

The films created for the Kinetoscope were short without much plot. They were centered on single ideas--a bodybuilder flexing, a couple kissing, a dance--rather than narratives, or stories. Edison soon developed the Kinetophone, which was a machine that could play music on a phonograph while visual images played. The films were mostly of people dancing to popular tunes, and did not focus on dialogue or narrative.

The Kinetoscope/Kinetophone were quickly overshadowed by technology that could show a film to a group of people at once by using a projector. The Lumière brothers in France invented a machine that could record, print film, and project images. Their Cinématographe was fairly light and portable. One of the very first films ever shown to a public audience was footage of a train arriving at a station. Here, we recommend that you go to YouTube or Vimeo to watch the short film that premiered in December of 1895: Arrival of a Train at Ciotat. Here is a poster advertising the Lumière's invention (the original painting was by Marcellin Auzole 1862-1942):

These early films consisted only of moving images. No sound was encoded with the visual. But that didn't mean that early film audiences sat in silence and watched the earliest movies. Live accompaniment--by solo pianists or guitarists, or even small ensembles--was part of the film-going experience. Edison eventually got on board with the whole projector idea, and by 1896 he had one of his own, called the Vitascope. Here's an ad for this Vitascope system:

(Notice the full orchestra playing for the film.)

As film became less of a novelty where you might see something you'd see in real life (like a train arriving at a station or someone sneezing), people began to develop narrative films, that is, films that told a story. The development of narrative films has come to be associated with two men, one American and one French. Edwin Porter was responsible for what is considered the first narrative film in America, The Great Train Robbery. (Hickman 2016, p. 68) Georges Méliès attended the Lumières' premiere, and--unsatisfied with the short non-narrative subjects--he built his own studio and started making movies. In total, he would make more than five hundred films. The most famous of these is A Trip to the Moon. We recommend watching this film or clips from it. It is usually available on Youtube or Vimeo for free.

In the early days, music for these films was often improvised by the musicians in individual theaters, meaning that seeing the same film in two different theaters could be a wildly different experience. Your understanding of the plot, the emotional connection you felt to characters or events, and even your ability to suspend disbelief and immerse yourself in the story were dependent, in part, on who was improvising the accompanying music. The musician or musicians' understanding of plot, characters, and events influenced what they played, as did their individual skills. An observant musician, who easily grasped the emotional beats of a film and who was able to apply a high level of playing skill to the task, would certainly give the audience a more satisfying viewing experience than an inattentive player with poor timing and limited skills. And what if your cinema pianist was just having a bad day at the job! Theater accompaniment could be a mixed bag.

In the next section, we're going to talk about some of the ways films were scored in the early days. This will include some of the ways that the conventions of film music--the language of film music--came to be established.

The Early Days

Film as a genre is over a century old, and music has always been part of the film-going experience, but modern film scores as we understand them--sometimes featuring newly written music, pre-existent music, or a combination of both--took a few decades to develop. We need to understand why that is and how it happened.

It’s an often-told anecdote that music was part of film from the beginning in part because something was needed to cover the noise of the projector. The earliest machines that allowed for the projection of film onto large blank spaces were hand cranked and noisy. In his book on film music, Kurt London said: “This painful noise disturbed visual enjoyment to no small extent. Instinctively cinema proprietors had recourse to music, and it was the right way, using an agreeable sound to neutralize one less agreeable.” (London, 28)

In time, the projectors would move from spaces where the audience sat to projection rooms with soundproofing. But by then, music was part of the film experience, fulfilling many important functions beyond just masking noise. Right now, let’s talk about the different ways a silent film might have music.

Improvisation

A musician (or musicians) improvised music along with a film. These improvisations might have been entirely new music, or the musical selections might have been drawn from pre-existent pieces. In the early 1920s, some enterprising folks like composer and conductor Erno Rapée published collections of music for cinema pianists. His Motion Picture Moods (1924) was a valuable resource for a solo musician who wanted a quick and easy way to sight-read music that had been categorized into “fifty-two moods and situations,” according to the title page. Some of these moods and situations included: “battle,” “gruesome,” “Misterioso,” and “sadness,” and included a host of dance forms and national songs (organized by nation or ethnic group). It had the added benefit of being a “Rapid-Reference” collection, and this was achieved by a handy list on the outer margin of each page, which would quickly send you to the next mood or situation you needed to accompany.

If you’re interested in seeing more of Motion Picture Moods, the Silent Film Sound and Music Archive has the entire book beautifully scanned at their website.

Cue Sheets

Now, Rapée’s book was a great resource, but it also required that the musician in the cinema quickly (and correctly) interpret the visuals on screen. There was no way to control what they chose. Enter cue sheets! The cue sheet was a list of musical cues (either pre-existent or newly written) suggested for scenes in a specific film. The idea for such a thing is usually credited to Max Winkler (although others assembled cue sheets as well), clerk at Carl Fischer, Inc. a music publisher based in New York.

In his account of the development of cue sheets, Winkler explained that one of the important credos of the film industry was this: “On the silent screen music must take the place of the spoken word.” (Cooke 6) When you think of it like that, it really drives home how important it was to get the music right. Winkler described the situation before cue sheets:

“Only in a few isolated theaters in big cities was any effort made to coordinate the goings-on on the screen with the sounds in the musical pit. Thousands of musicians never had a chance to see a picture before they were called upon to play music for it! There they were sitting in the dark, watching the screen, trying to follow the rapidly unfolding events with their music: sad music, funny music, slow music—sinister, agitated, stormy, dramatic, funereal, pursuit, and amorous music. They had to improvise, playing whatever repertoire came to their worried minds, or whatever they made up themselves on the spur of a short moment. It was a terrible predicament—and so, usually, was the music.” (Cooke 6-7)

To fix this, Winkler proposed making a list to go with a film (and selling the sheet music from Carl Fischer, of course). He drew this example up for an imaginary movie: (Cooke 8)

MUSIC CUE SHEET

for

The Magic Valley

Selected and compiled by M. Winkler

Cue

- Opening—play Minuet No. 2 in G by Beethoven for ninety seconds until title on screen “Follow me dear.”

- Play—“Dramatic Andante” by Vely for two minutes and ten seconds. Note: Play soft during scene where mother enters. Play Cue No. 2 until scene “hero leaving room.”

- Play—“Love Theme” by Lorenze-for one minute and twenty seconds. Note: Play soft and slow during conversations until title on screen “There they go.”

- Play—“Stampede” by Simon for fifty-five seconds. Note: Play fast and decrease or increase speed of gallop in accordance with action on the screen.

In 1912 Winkler wrote to Universal Film Company and shared his idea for the cue sheet. Soon, he was being shown screenings of films before they were distributed, and he was suggesting pre-existent pieces for the various scenes and moods. You can imagine that many musical cliches were forged in this process—some of which we still live with today. Orchestras who played in movie houses were concerned about repeating music, so once you used, say, Brahms’ Lullaby for a movie, it was out as a choice for a few months after. This meant that new music was going to have to help meet the demand. Composers were hired to write the cues music that the rapid distribution of films required. Still unable to meet the extremely high demand, they took to arranging works that weren’t under copyright. As Winkler puts it: “We began to murder the works of Beethoven, Mozart, Grieg, J.S. Bach, Verdi…” (Cooke 11). Simply put, it was a frenzy. And the sudden popularity of cue sheets died out suddenly as well, with the advent of sound film. More on that later.

Compilation scores

This is a somewhat glorified version of the cue sheet, but one that was not tied to a publishing house. Instead, the “most ambitious musical accompaniments for silent films were those offered by the huge picture palaces in major cities.” (Cooke 16) These theaters had enormous orchestras and many musicians at their disposal. Also, the practice of creating scores in this manner roughly coincided with Hollywood epic films like the controversial Birth of a Nation. When Birth of a Nation premiered in 1915, Joseph Carl Breil’s “compilation score” replaced the classical pieces chosen by Carli Elinor. These types of scores, facilitated by the music directors at major theaters, used pre-existent music and newly written music. According to a 1920 article in American Organist, music directors took great pains to choose music that would support the dramatic action without pulling focus from the action on screen. They would cut, arrange, and time out musical selections to fit a film. They might also require that certain aspects—like opening titles—be projected at a faster or slower rate to fit the musical selections. This was a time-consuming art form. (Cooke 19) In extreme cases (like Birth of a Nation), a group of musicians might actually travel along with a film, like a tour. (New Grove, "Film Music," 549)

In the 1980 New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (a well-respected music encyclopedia) article on “Film Music” talks about these scores and their influence:

“The music director studied the film with his librarian, selecting music and arranging the cues for changes of scene. He was helped by a suggestion list (sent with the film); the pieces recommended were obtainable in arrangements for all sizes of orchestra from 50 players (in the larger theaters) down to five (the usual size of the band that relieved the orchestra for brief intervals). The silent film thus acquainted millions of people with ‘classical’ music, even if in modified form, and created lucrative employment for many performing musicians.” (New Grove, "Film Music" 549)

Things would begin to change with “talkies,” or motion pictures with synchronized sound. This happened in 1927. For now, let's get a little deeper into scoring methods for silent films.