13: Proposals

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

- Utilize audience analysis to plan, write, and revise a proposal.

- Explain the proposal process and various proposal types.

- Format and organize a written proposal.

- Adapt the style and content of a proposal based on the type of proposal and audience analysis.

In a technical writing course, the proposal is an opportunity for you to present an idea to a specific, named audience about an idea you have that company, organization, center, or other business. Whatever topic you choose, you must be able to conduct thorough research that you will integrate into your final report.

To begin planning a proposal, remember the basic definition: a proposal is an offer or bid to complete a project for someone. Proposals may contain other elements—technical background, recommendations, results of surveys, information about feasibility, and so on. But what makes a proposal a proposal is that it asks the audience to approve, fund, or grant permission to do the proposed project.

A proposal should contain information that would enable the audience of that proposal to decide whether to approve the project, to approve or hire you to do the work, or both. To write a successful proposal, put yourself in the place of your audience—the recipient of the proposal—and think about what sorts of information that person would need in order to feel confident having you complete the project. Consider the example of a proposal written to a supervisor at a solar power company suggesting the creation of a policy manual for residential solar panel installers. The proposal’s audience may be an executive, whose knowledge of the technicalities may be very broad. Let’s imagine the executive approves the proposal and requests completion of the manual, which will be produced well after the proposal. The manual’s audience is the technicians, who may have more specialized knowledge than the executive. The content and language used for these two different audiences will need to be adjusted to fit the writing situation.

It is easy to confuse proposals with other kinds of documents in technical writing. Imagine that you have a terrific idea for installing some new technology where you work, and you write up a document explaining how it works, showing the benefits, and then urging management to install it. Is that a proposal? All by itself, this would not be a complete proposal. It would be more like a feasibility report, which studies the merits of a project and then recommends for or against it. However, all it would take to make this document a proposal would be to add elements that ask management for approval for you to go ahead with the project. Additionally, for some technical writing classes offered in college, one of those elements may be scholarly research. Certainly, some writers of proposals must sell the projects they propose, but in all cases, proposals must sell the writer (or the writer’s organization) as the one to complete the project.

Types of Proposals

Consider the situations in which proposals occur. A company may send out a public announcement requesting proposals for a specific project. This public announcement—called a request for proposals (RFP)—could be issued through websites, emails, social media, newspapers, or trade journals. Firms or individuals interested in the project would then write proposals in which they summarize their qualifications, project schedules and costs, and discuss their approach to the project. The recipient of all these proposals would then evaluate them, select the best candidate, and then work up a contract.

But proposals also come about much less formally. Imagine that you are interested in doing a project at work (for example, investigating the merits of bringing in some new technology to increase productivity). Imagine that you met with your supervisor and tried to convince him or her of this. They might respond by saying, “Write me a proposal and I’ll present it to upper management.” This is more like the kind of proposal you will write in a technical writing course.

Most proposals can be divided into several categories:

- Internal, external: A proposal to someone within your organization (a business, a government agency, etc.) is an internal proposal. With internal proposals, you may not have to include certain sections (such as qualifications) or as much information in them. An external proposal is one written from one separate, independent organization or individual to another such entity. A typical example is an independent consultant proposing to do a project for another firm. This kind of proposal may be solicited or unsolicited, as explained below.

- Solicited, unsolicited: A solicited proposal is one in which the recipient has requested the proposal. Typically, a company will send out requests for proposals (RFPs) through the mail or publish them in some news source. But proposals can be solicited on a very local level: for example, you could be explaining to your boss what a great thing it would be to install a new technology in the office; your boss might get interested and ask you to write up a proposal that offered to do a formal study of the idea. Unsolicited proposals are those in which the recipient has not requested proposals. With unsolicited proposals, you sometimes must convince the recipient that a problem or need exists before you can begin the main part of the proposal.

Scenarios for Proposals

Many of you may have never given much thought to producing a technical report based on a viable proposal. Here are some sample proposal ideas to ponder:

- Imagine that a company has a problem or wants to make some sort of improvement. The company sends out a request for proposals; you receive one and respond with a proposal. You offer to come in, investigate, interview, make recommendations—and present it all in the form of a report.

- An organization wants a seminar in your expertise. You write a proposal to give the seminar—included in the package deal is a guide or handbook that the people attending the seminar will receive.

- An agency has just started using a new online data system, but the user’s manual is technically complex and difficult to read. You receive a request for proposals from this agency to write a simplified guide or startup guide.

- Imagine that a nonprofit organization focused on a particular issue wants a consultant to write a handbook or guide for its membership. This document will present information on the issue in a way that the members can understand.

Not all research topics are appropriate for technical writing. Topics that are based on values and beliefs do not fall into the category of technical writing. Historical and literary topics do not qualify.

Sections in a Proposal

You have the following options for the format and packaging of your proposal. It does not matter which you use as long as you use the memorandum format for internal proposals and the business-letter format for external proposals.

- Cover letter or memo with a separate proposal: In this format, you write a brief "cover" letter or memo and attach the proposal properly after it. The cover letter or memo briefly announces that a proposal follows and outlines the contents of it. In fact, the contents of the cover letter or memo are pretty much the same as the introduction (discussed in the previous section). Notice, however, that the introduction to the proposal proper that follows the cover letter or memo repeats much of what preceded. This is because the letter or memo may get detached from the proposal or the recipient may not even bother to look at the letter or memo and just dive right into the proposal itself.

- Consolidated business-letter or memo proposal: In this format, you consolidate the entire proposal with a standard business letter or memo. You include headings and other special formatting elements as if it were a report.

The following provides a review of the sections you will commonly find in proposals. Do not assume that each one of them has to be in the actual proposal you write, nor that they have to be in the order they are presented here. Refer to the assignment sheet provided by your instructor and consider other kinds of information unique to your topic that should be included in your particular proposal.

Introduction. Plan the introduction to your proposal carefully. Make sure it does all of the following things (but not necessarily in this order) that apply to your particular proposal:

- Indicate that the content of the memo is a proposal for a specific project.

- Develop at least one brief motivating statement that will encourage the recipient to read on and to consider approving the project (especially if it is an unsolicited or competitive proposal).

- Give an overview of the contents of the proposal.

Background on the problem, opportunity, or situation. Often occurring just after the introduction, the background section discusses what has brought about the need for the project—what problem, what opportunity exists for improving things, what the basic situation is. For example, management of a chain of daycare centers may need to ensure that all employees know CPR because of new state mandates requiring it, or an owner of Pine Timberland in eastern Oregon may want to get the land producing saleable timber without destroying the environment.

While the named audience of the proposal may know the problem very well, writing the background section is useful in demonstrating your particular view of the problem. Also, if the proposal is unsolicited, a background section is almost a requirement—you will probably need to convince the audience that the problem or opportunity exists and that it should be addressed.

Benefits and feasibility of the proposed project. Most proposals briefly discuss the advantages or benefits of completing the proposed project. This acts as a type of argument in favor of approving the project. Also, some proposals discuss the likelihood of the project’s success. In an unsolicited proposal, this section is especially important—you are trying to “sell” the audience on the project.

Description of the proposed work (results of the project). Most proposals must describe the finished product of the proposed project. In a technical writing course, that means describing the written document you propose to write, its audience and purpose; providing an outline; and discussing such things as its length, graphics, binding, and so forth. In the scenario you define, there may be other work such as conducting training seminars or providing an ongoing service. At this early stage, you might not know all that it will take to complete your project, but you should at least have an idea of some of the steps required.

Method, procedure, theory. In some proposals, you will need to explain how you will go about completing the proposed work. This acts as an additional persuasive element; it shows the audience you have a sound, thoughtful approach to the project. Also, it serves to demonstrate that you have the knowledge of the field to complete the project.

Schedule. Most proposals contain a section that shows not only the projected completion date but also key milestones for the project. If you are doing a large project spreading over many months, the timeline would also show dates on which you would deliver progress reports. If you cannot cite specific dates, cite amounts of time for each phase of the project.

Costs, resources required. Most proposals also contain a section detailing the costs of the project, whether internal or external. With external projects, you may need to list your hourly rates, projected hours, costs of equipment and supplies, and so forth, and then calculate the total cost of the complete project. Internal projects, of course, are not free, so you should still list the project costs: hours you will need to complete the project, equipment and supplies you will be using, assistance from other people in the organization, and so on.

Conclusions. The final paragraph or section of the proposal should bring readers back to a focus on the positive aspects of the project. In the final section, you can urge them to contact you to work out the details of the project, remind them of the benefits of doing the project, and maybe make one last argument for you or your organization as the right choice for the project.

Special project-specific sections. Remember that the preceding sections are typical or common in written proposals, not absolute requirements. Always ask yourself what else might your audience need to understand the project, the need for it, the benefits arising from it, your role in it, and your qualifications to do it. What else do they need to see in order to approve the project and to approve you to do it?

Organization of Proposals

As for the organization of the content of a proposal, remember that it is essentially a sales or promotional kind of thing. Here are the basic steps it goes through:

- Introduce the proposal, telling the readers its purpose and contents.

- Present the background – the problem, opportunity, or situation that brings about the proposed project. Get the reader concerned about the problem, excited about the opportunity, or interested in the situation.

- State what you propose to do about the problem, how you plan to help the readers take advantage of the opportunity, how you intend to help them with the situation.

- Discuss the benefits of doing the proposed project, the advantages that come from approving it.

- Describe exactly what the completed project would consist of, what it would look like, how it would work – describe the results of the project.

- Discuss the method and theory or approach behind that method – enable readers to understand how you'll go about the proposed work.

- Provide a schedule, including major milestones or checkpoints in the project.

- List your qualifications for the project; provide a mini-resume of the background you have that makes you right for the project.

- Now (and only now), list the costs of the project, the resources you'll need to do the project.

- Conclude with a review of the benefits of doing the project (in case the shock from the costs section was too much), and urge the audience to get in touch or to accept the proposal.

Notice the overall logic of the movement through these sections: you get them concerned about a problem or interested in an opportunity, then you get them excited about how you'll fix the problem or do the project, then you show them what good qualifications you have – then hit them with the costs, but then come right back to the good points about the project.

Format of Proposals

You have the following options for the format and packaging of your proposal. It does not matter which you use as long as you use the memorandum format for internal proposals and the business-letter format for external proposals.

The examples below layout the differences and similarities of a cover letter or memo.

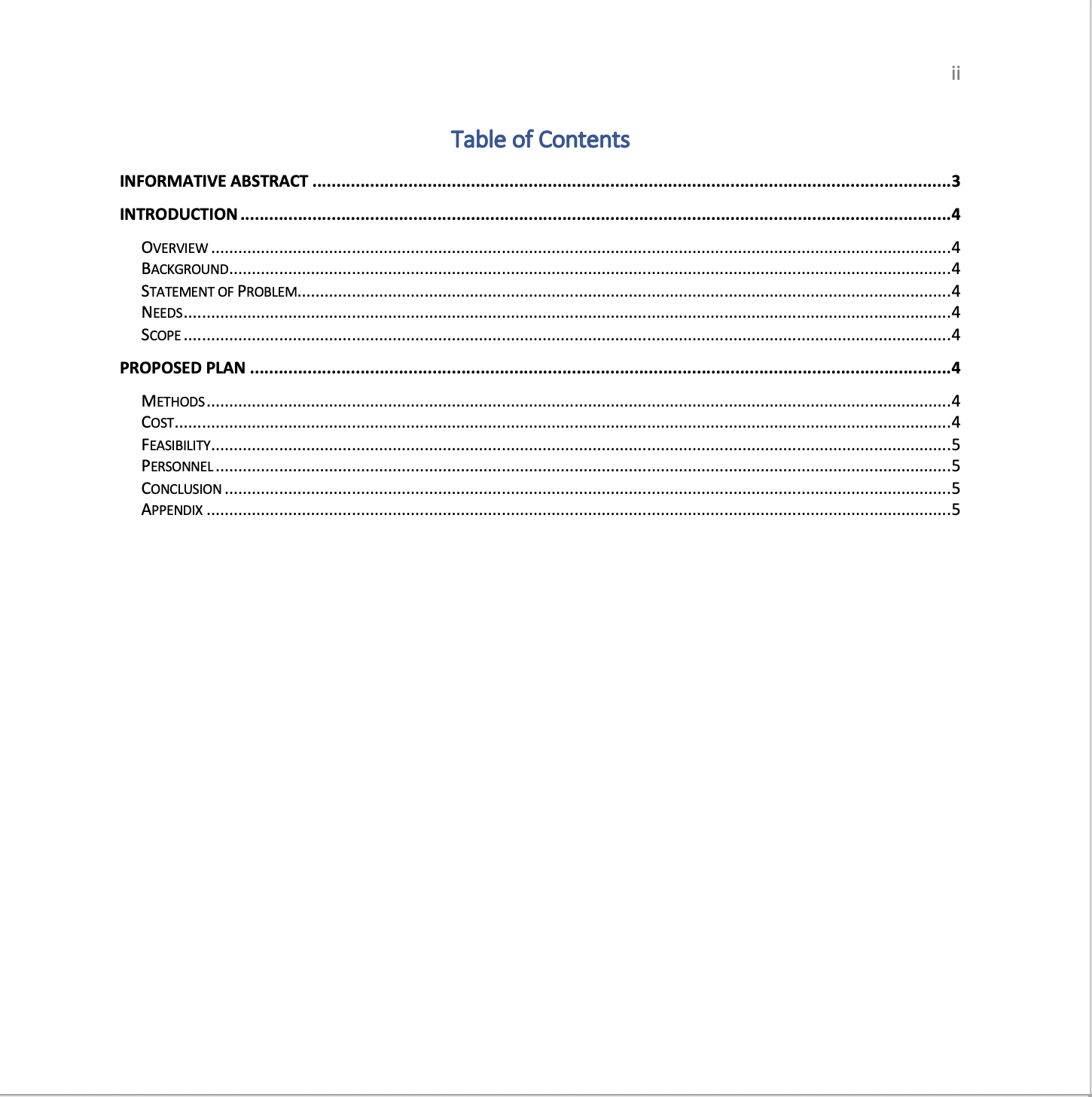

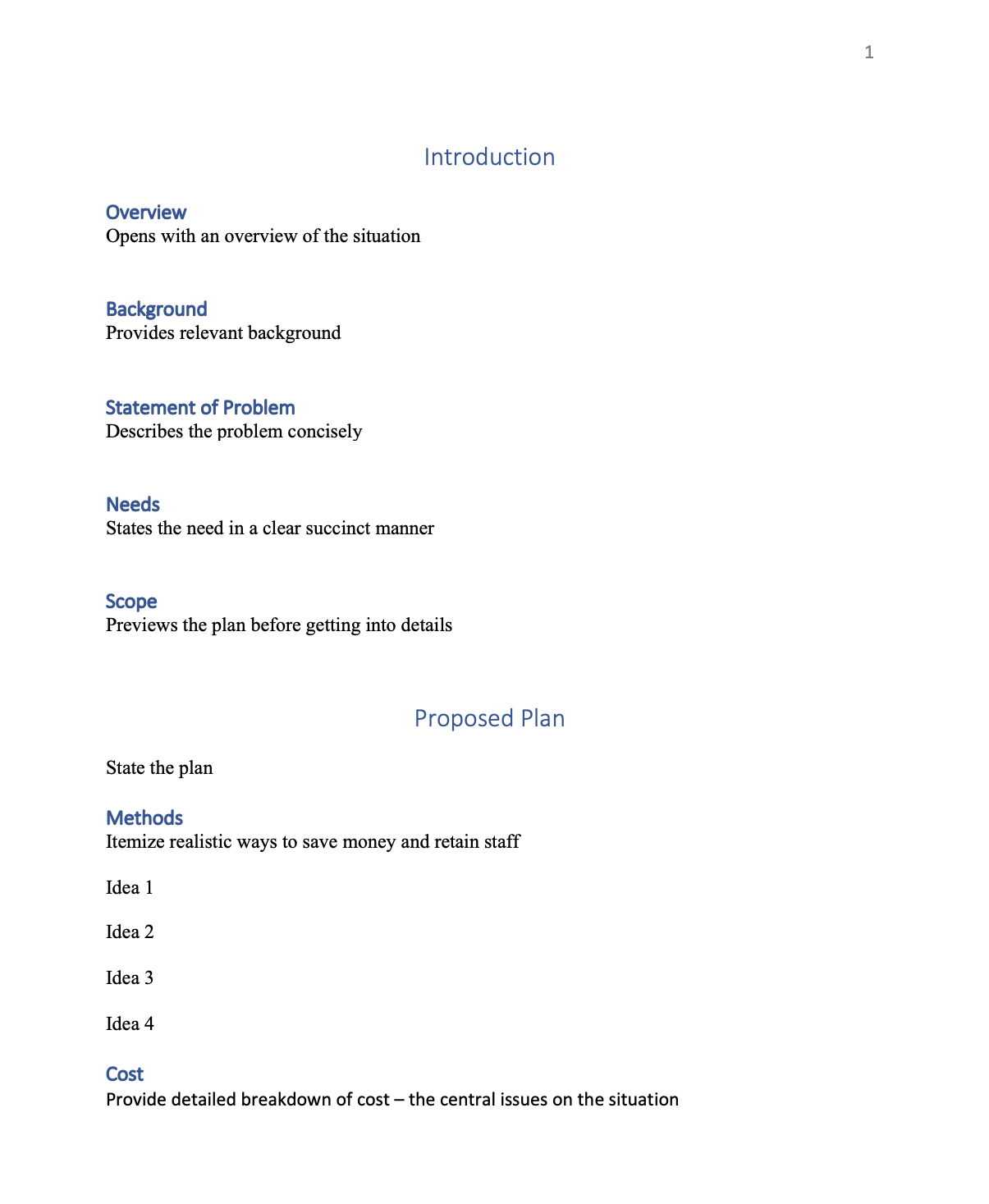

Sample formal Proposal layout

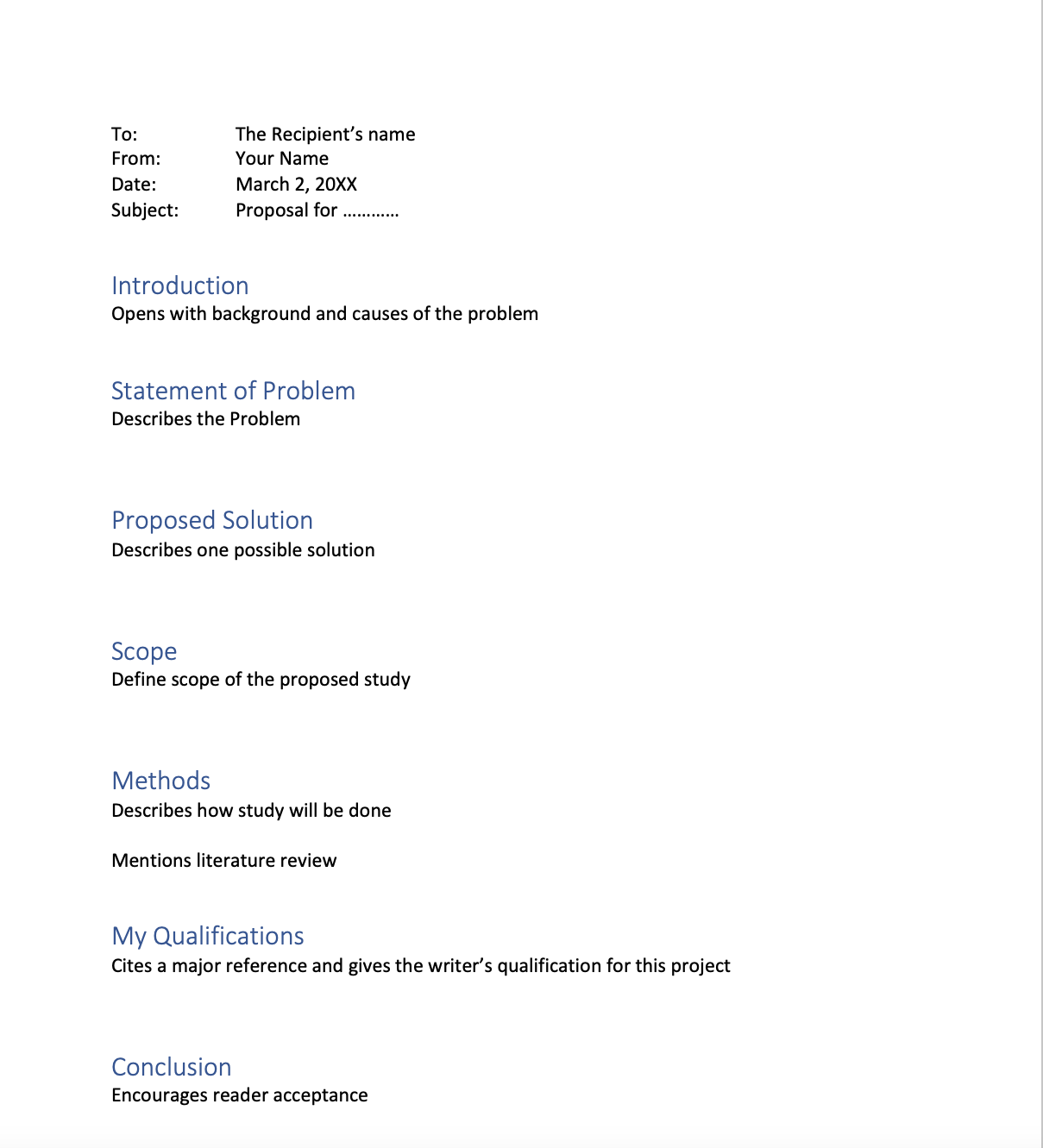

Sample Research Proposal

Hopefully, when the time comes for you to create a proposal, the steps in this chapter will help you create one that will engage your audience and get your idea or product accepted. As a reminder, a proposal should contain information that would enable the audience of that proposal to decide whether to approve the project, to approve or hire you to do the work or both. Make sure to always read the requirements for the proposal; especially, if it is going to an external client. Do research on your audience, so you know how to gear the proposal to them for acceptance. The content in this chapter will help you prepare proposals for various audiences.

As you reread and revise your proposal, keep the following tips in mind:

- Use the right format. Remember, the memo format is for internal proposals; the business-letter format is for proposals written from one external organization to another. (Whether you use a cover memo or cover letter is your choice.)

- Write a good introduction as discussed in the preceding, and identify exactly what you are proposing to do.

- Make sure that a report – a written document – is somehow involved in the project you are proposing to do. Remember that in a technical writing course we are trying to do two things: write a proposal and plan a term-report project.

- Organize the sections in a logical, natural order. For example, don't hit the audience with schedules and costs before you've gotten them interested in the project.

- Break out the costs section into specifics; include hourly rates and other such details. Don't just hit them with a whopping big final cost.

- For internal projects, don't omit the section on costs and qualifications: there will be costs, just not direct ones. For example, how much time will you need, will there be printing, binding costs? Include your qualifications – imagine your proposal will go to somebody in the organization who doesn't know you.

- Address the proposal to the real or realistic audience – not your instructor. (You can use your instructor's name as the CEO or supervisor of the organization you are sending the proposal to.)

- Watch out for generating technobabble. Yes, some of your proposal readers may know the technical side of your project – but others may not. Challenge yourself to bring difficult technical concepts down to a level that nonspecialists can understand.

- Include all the information listed in "Special assignment requirements". If it doesn't logically or naturally fit in the proposal itself, put it in a memo to your instructor.

This chapter was derived by Annemarie Hamlin, Chris Rubio, and Michele DeSilva, Central Oregon Community College, from Online Technical Writing by David McMurrey – CC: BY 4.0 and David McMurrey, Saylor.org and Saylor English 210 Technical Writing, used under a CC BY license. "Proposal" is licensed under CC BY 4.0 by Lise-Pauline Barnett.