There are various ways to discuss style. We can divide style into high, medium, and low styles. We can also divide style into the Anglo-Saxon and the Latinate styles. There are also other ways to categorize different styles. But we will look at these two ways.

High, medium, and low styles

For the most part, in writing texts, you want to use common expressions, rather than coming up with something elegant or complicated. We might call this writing in a low style. In some situations, you may want to choose this “low style.” It is sometimes also called the “plain” style. This would mean you sometimes even include slang, and your sentences are shorter. Your writing would sound more like spoken language than written language. You would not use much figurative language or many images. You would sound matter of fact. Most newspaper writing is done in the “plain” or “low” style.

You also may want to try to write in a high style. Think of a fashionable woman walking down Fifth Avenue in New York City dressed in the height of fashion. She has on a diamond and ruby-encrusted necklace. She has a Kate Spade purse, a Hermes silk scarf, and her skirt is long, folded and flared, swishing above her Malono Blahnik heels. This is like high style. It is not the jeans and white T-shirt of low style. Writing in a high style means you use words that are more obscure, or even archaic. You are extravagant with your word choices, and perhaps you adorn your content with a wealth of images and metaphors. Your sentences are probably longer and often have many clauses. You might even have alliteration and sound patterning. You choose uncommon or hard-working verbs, and you really put the dictionary to use.

The beginning of the Declaration of Independence, we might say, is probably closer to a high style.

When in the Course of human events it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation. (Jefferson)

If it were a low to medium style, it might look more like this:

As time goes by, sometimes one group of people find it necessary to separate themselves from another country that they are part of. According to the laws of nature, they are most certainly allowed to do this. But when they separate themselves, in order to stay in good favor among the other people who live on earth, they should state why they are separating.

A lower style would be somewhere even more casual, or simple. Something like:

Sometimes folks in one country have to break away from the others. This is probably fine if they do, but if they do this, they should tell why. Just to be fair and keep a good reputation.

We don’t have to divide styles into high, medium, and low. Perhaps a more useful way to discuss them is to use the two categories of “spare/simple” and “adorned.” Some people also describe these styles as “Anglo-Saxon” and “Latinate.” The “Anglo-Saxon” style would roughly correspond to the “spare/simple” style and the “Latinate” style would roughly correspond to the “adorned” style.

The Anglo-Saxon, or “spare” style means that you use words that come from Germanic, or Old Norse, or Old English roots. These words are almost always shorter than Latinate words. These words are the most basic building blocks of the English language. Anglo-Saxon words are mostly simple words. For example, in an unadorned and folksy way, you bid a “hearty welcome” to your guests. If you were to give your guests a “cordial reception,” you would be shifting to a more Latinate style. The roots of the words “heart” and “welcome” are Anglo-Saxon. The roots of “cordial” and “reception” are Latinate (or Greek, which tends to be the same thing, for our purposes). Here is a brief list of Anglo-Saxon words and their Latinate “equivalents”:

| Anglo-Saxon |

Latinate |

| Choke |

Asphyxiate |

| Forsaken |

Relinquished |

| Drunk |

Inebriated |

| Answer |

Response |

| Ask |

Inquire |

| Thing |

Item |

| Aware |

Cognizant |

| Before |

Prior |

| Belly |

Abdomen |

| Murder |

Homicide |

| Angry |

Apoplectic |

Notice that Anglo-Saxon words tend to be shorter. Notice that the Latinate words tend to be words that are also technical terms. For example, a medical doctor will describe almost everything relating to your body in exclusively Latinate (Greek) terms; she will call your “tummy” (Anglo-Saxon) your “abdomen” (Latinate).

You also notice that when writing has more Latinate words, it usually sounds loftier, more educated and erudite and even hoity-toity. But an Anglo-Saxon style tends to sound more folksy, down-to-earth, and often, more truthful.

Here is an example of a mix of the two styles. This is Lincoln’s “Gettysburg Address.” Many of the key Anglo-Saxon words are in red, and the key Latinate words are marked in blue.

Fourscore and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation or any nation so conceived and so dedicated can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting-place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this. But in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead who struggled here have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here… (Lincoln)

Notice, among other things, that Lincoln tends to use two words for one idea, such as “fitting and proper” and “so conceived and so dedicated” and “little note nor long remember.” And when he gets to his idea of what we cannot do, he uses three negative forms of similar verbs, “dedicate” and “consecrate” and “hallow” in the line: “We cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground.”

Considerations of style

Variation in word choice

This brings us to the topic of word choice, which is sometimes called diction. Making a good choice of how to vary the expression when you are repeating the same thing is a matter of long immersion in the language of English. Your word choices are often the most revealing of your style. You can write:

He has deceived you, he has lied to you—he is even now prevaricating.

Or you could write,

He is lying, I tell you, he is lying. And he lies in every word!

These are different ways to speak, and depend on the audience, and the context, and your purpose as well.

As mentioned above, it is good to repeat yourself prudently. But when you do, you can use different words. You are basically resaying what you want to say in a few different ways. This is because your reader needs to be kept on topic. They need to be reminded again and again of your main point.

Figurative language

Above we talked about metaphor, in explaining style and tone. Metaphor is also a part of figurative language. The figurative language (the making-to-be-seen-vividly language) that you use to describe the abstract (that which cannot be seen) is sometimes the most important choice you make in writing situations.

When you want to talk about “happiness,” do you tell your audience that happiness is, as Charles Schulz had it, “a warm puppy”? Everybody can see a warm puppy. Or do you state something more on the lines of what Confucius said, that “happiness” (an abstract concept) is “to study” and “to meet friends.” Or do you just use the word “happiness” and not worry about being sure that your audience has the same definition of happiness that you have?

We have a saying that “seeing is believing.” You want your reader to see what you are writing, so you use words to make image-productions (figurative language) that bring it before the audience’s mental eyes vividly. As Horace wrote, “Less vividly is the mind stirred by what finds entrance through the ears than by what is brought before the trusty eyes, and what the spectator can see for himself” (465).

Remember that these figures, or image-productions, are basic to writing. You do well to create word-visualizations when you write creatively, as well as when you write for more informative purposes.

For example, are you writing a history paper trying to inform about George Washington? You could organize the paper around a visual of the puzzle and begin,

There were many pieces that came together to make up the life of George Washington. The first piece of the puzzle was that he was a general. Another piece of the puzzle was that he was a manager.

Using the visual of the puzzle might keep your audience following your argument better. They will keep waiting for that next puzzle piece that starts each paragraph.

Or what if you were to write a news story about a protest? What was the protest like? Could you start by writing, “The protest on the lawn of the president’s house last Saturday was more like a gathering of lost doves than a feast of dragons.” Then you could go on to show how quiet the protest was. For some audiences, the images of doves and dragons might work to quickly get them to the feeling of what it was like to be at the protest.

Even in a scientific paper, you might want to think about word-visualizations (image productions, figurative language). The famous psychologist John B. Watson wrote that, “The behaviorist, in his efforts to get a unitary scheme of animal response, recognizes no dividing line between man and brute” (158). Ask yourself why he used “dividing line” rather than “difference” or “demarcation” or “separation marking”?

What about the famous computer scientist, Alan Turing’s opening lines of his article “Computing Machinery and Intelligence”? He wrote:

I propose to consider the question, “Can machines think?”; This should begin with definitions of the meaning of the terms “machine” and “think”?...The new form of the problem can be described in terms of a game which we call the “imitation game” (Turing 433).

Now ask yourself: how carefully Turing is choosing his words? And why does he choose a more physical, visable, see-able, concept “game” to describe the answer to a question about the “mind” which nobody can see, and “thinking” which nobody can see?

And finally, notice how scientists Tversky and Kahneman, writing about how we make decisions, start one of their most famous papers by giving three concrete examples that we can all see and relate to, and visualize easily: an election result, a guilty defendant, and a dollar. They write,

Most important decisions are based on beliefs concerning the likelihood of uncertain events such as the outcome of an election, the guilt of a defendant, or the future value of the dollar (1).

Metaphor is saying something by means of something else, as we described above. Usually what you are saying is something abstract, something you cannot see, and what you are using to say it is something concrete, something you can see. Metaphor is like simile. The only difference between a simile and a metaphor is that a simile includes the word “as.” So, for example, a metaphor is “I am a dove.” A simile is “I am like a dove.” Another example is the 80's song by Pat Benatar: "Love is a battlefield." A simile for the same would be "Love is like a battlefield."

There are many different technical terms besides image-production, metaphor, and simile (or allegory and analogy) used to describe this same thing: you need to make what you are saying visual (mentally see-able) to people. The star is twinkling in the sky. How can I say that more visually? How about “like a diamond in the sky”? But that is almost a cliché; most audiences would not think it is fresh. I have to come up with something more striking. This is not easy, and some people are just naturally good at it—they think in metaphor.

So how can I describe that twinkling star? Maybe scientifically, “the star, a pulsing astronomical scintillation.”

You can also think of these “image-productions” as symbols. What does the American flag symbolize? A flag is something you can see, and, in this case, it stands for abstract ideas like love of country, freedom, and democracy.

Parallelism, rhythm, and repetition

One of the rules of finding a good style that fits you, your subject matter, and your audience, is to think about nature. Thus, it is good to know that the natural rhythm of the English language is to have one syllable that is emphasized, followed by another that is not, followed by another that is; or, to start with a syllable that is not emphasized, and then have one that is, and then one that is not, and so on. So, it is one-two, one-two pattern, or one-two, one-two.

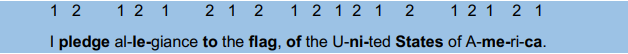

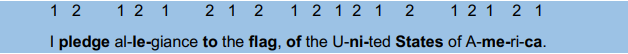

For example, the American pledge of allegiance is not a poem. It is prose. And it begins with a non-emphasized syllable. If we write in the counting, and make bold the emphasized syllables, we have:

Notice that the natural rhythm of non-emphasized syllable followed by emphasized syllabue only breaks down twice: right after “flag” and then it corrects immediately, and right after the “of” the precedes the word “America.”

When people make choices of wording as they write, they often exploit this natural pattern of English. For example, what if you wrote,

He is run-ning quick-ly.

Because “quickly” ends with a non-emphasized syllable, it trails a bit more than

He is running fast.

In the sentence “He is running fast,” the word “fast” is somewhat more emphasized, and thus the sentence ends on a strong beat (to use a metaphor from music). To choose “He is running quickly” over “He is running fast” has the subtle effect of slightly making your sentence more soft, or less direct.

Let’s look at an example. In the last paragraph of Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart” Poe writes, “I foamed --I raved --I swore!” How would this sound in terms of impact on the mental hearing, if he had written, “I foamed --I raved --I anathematized!”? Poe did not repeat three verbs exactly; he did not write “I foamed, I foamed, I foamed,” although he did repeat the pronoun “I” three times. But he did repeat the sound pattern—the pronoun “I,” followed by the one-syllable verb. And later on in that final paragraph he plays with this same exact sound pattern, by varying the middle section a bit: “They heard! --they suspected! --they knew!”

Poe, like most writers who really want to hit people hard and fast with their meaning clearly, choses almost all short, one-syllable words. If you fit this idea in with the knowledge we discussed above, that English is a language that naturally tends to have one emphasized syllable followed by another non-emphasized syllable, followed by an emphasized syllable, and so on, you notice that Poe is very much depending on verbs and nouns.

I gasped for breath.

I paced the floor.

This constant use of the short words, with nouns and verbs (the verbs above are “to gasp” and “to pace”) filling in the spaces where the emphasized syllable is, tends to have the effect of highlighting some of the longer, less compact words when they do appear at times. For example, when he writes of his “violent gesticulations” in that last paragraph of “The Tell-Tale Heart,” the word “gesticulations” is sort of flailing about waving its many syllables around, just as Poe is waving his hands about in the story. For he doesn’t write “violent hand-wavings.”

When writing headings and titles, pay attention to the sounds and rhythms. And when writing anything that you want people to really remember well, keep these truths about the English language in mind. For example, are you writing a memoir? How are you going to describe the treehouse that you built, and someone burnt it down and killed a dog in it? “My treehouse burnt down that year, and the neighbor’s dog died in the fire.” Or “Somebody burned down my treehouse. The neighbor’s dog was tied up in the treehouse at the time. And so he perished in the flames.”

Person

“Call me Ishmael.” This is the first line of the novel Moby Dick. How would this book feel, to start, if it began, “He was called Ishmael”? This is a choice of persons. “Call me Ishmael” is in the second person. One person addresses another directly. “He was called Ishmael” is third person. One person talks to another person about a third person.

Do you want to write in the first person, using “I”? Or do you want to write in the third person, talking always about “them,” and “he” and “she”? Do you ever want to address your audience (second person)? Would you do it by writing,

What do you think, friend, about the judicial branch?

This is second person. Or would you write,

One wonders what others think about the judicial branch?

This is third person.

Chart: person: Singular / Plural

| |

Singular |

Plural |

| First Person |

I, me, my, mine |

We, us, our |

| Second person |

You, your |

You, yours |

| Third person |

he / she / it, him/her/it, his/her/its |

They, them, their |

In nature, when you are standing facing someone and speaking to them, you say “you” to the person. And when you are talking to yourself, you are in your own mind saying “I.” And when you are talking about someone else, to another person, you are saying “he” or “she” or “it,” referring to that third person. Notice that if you mentally visualize each of these three situations, these situations are about distance, familiarity, and remoteness. Your choice of persons makes a difference in your style.

Verb and noun choice

This brings us to nouns and verbs. Nursery rhymes are almost completely made up of nouns and verbs. In music, when we sing and are given a choice of where to emphasize the word, we always choose a noun or verb naturally, over an adjective or a helping verb, or an article, and the like. This is because our brains simply know that the adjectives, helping verbs, and articles, are not as important as the verbs and nouns.

A sentence has meaning if there is a subject (noun) and a verb. The rest is extra. For example,

Silly enthusiastic Joe bright

is not a sentence. It needs a verb to be a sentence.

Remember what we discussed above, about making things visible. In nature, we see objects. And the objects are doing or being something. Thus, for the most part, it is better to have your writing heavily dependent on verbs and nouns. They are more visible than adjectives. Good writers use adjectives and adverbs sparingly. This is true in writing about anything, including science. For example, read the following opening lines from Albert Einstein’s “On the electrodynamics of moving bodies”:

It is well known that Maxwell’s electrodynamics—as usually understood at present—when applied to moving bodies, leads to asymmetries that do not seem to attach to the phenomena. Let us recall, for example, the electrodynamic interaction between a magnet and a conductor (140).

What if we added in adjectives and adverbs:

It is certainly well known that Maxwell’s interesting electrodynamics—as usually understood at present---when applied to moving bodies, leads to complicated asymmetries that do not seem to attach to the phenomena. Let us briefly recall, for example, the electrodynamic interaction between a chosen magnet and a certain conductor.

You begin to see how unnecessary they are.

You can not only break down sentences into parts of speech, but you can even go the level of watching your vowels and consonants to create a certain style flow.

Sentence style

This brings us to sentences. A word alone is not much. But once you put it into a sentence, it is joined into a marvelous number of relationships that we can call “syntax.” This makes the rules of a sentence, especially the rules relating to the verb, the sun around which everything in the sentence turns.

Let’s take an example. You can write

The cat wore a hat

You have a subject “the cat” and a verb “wore” and an object “hat.” What if you were to write this instead?:

The hat wore a cat.

Now, following the rules, “hat” is the subject and the cat must be somewhere on the hat. So this is different. But to return to the first example:

The cat wore a hat.

How did the cat wear the hat?

The cat wore the hat stubbornly.

But what if we want to really emphasize the cat’s stubbornness? We could write, with a slightly different meaning

Stubbornly, the cat wore the hat.

And what if we wrote

The cat wore the hat, stubborn.

Now we have some purposeful ambiguity here. If a modifier is before a word it modifies, it can only modify (or, give more information about) that word. So if it said “The stubborn hat wore the hat” we have no choice about using “stubborn” to modify “cat.” But, put where it is in the above example, “stubborn” might also modify “hat.” According to the natural meanings of “cat” and “hat” it is more likely that most people would assume “stubborn” here modifies “cat” and not “hat”, but the possibility is at least there.

A sentence is, simply, a complete thought. We also say a sentence has to have a subject and a verb. But more than these, a sentence is “an organization of items in the world” and “a structure of logical relationships” (Fish 14). Your sentencing choices are a big part of your style.

Allusion

Let’s say you are writing about your bosses mistreating the employees, and you write,

It seems like we are just like flies to wanton boys to the bosses.

In so doing, you are alluding to the line from King Lear, by Shakespeare, where he says,

As flies to wanton boys are we to th’ gods:

They kill us for their sport (Act 4, Scene 1).

By using the words from Shakespeare, you are not just enriching your writing by putting the strong and vivid image of boys swatting flies into it. You are also pulling in some of the sense, or feeling, or pathos and tragedy of Shakespeare’s play into your own writing. This, of course, assumes that your audience is familiar with Shakespeare’s play.

For example, if someone is worried that they are late, they might not just say very blandly,

I’m going to get into trouble if I am late.

They might say, more vividly,

I’m going to turn into a pumpkin if I am late.

And this is alluding to the story of Cinderella. Or a student released from the final class on the last day of school might sing out, “I am free at last! I am free at last!” alluding to Martin Luther King Jr’s “I have a dream” speech.

Thus, some rules of allusion are:

- You probably should not allude to things that at least some of your audience is not familiar with.

- By allusion, you are using another writer’s words as a short-cut to achieve the image or feeling you are aiming at.

- Allusion is not plagiarism, and you do not have to put quotation marks around the words in your text that are taken directly from another text in order to allude to it. This is because the citation is already in the minds of the audience. They know you didn’t “steal” it. They know you didn’t intend to pass off the other writer’s words as your own.

- People tend to allude to popular songs of the day by the most popular singers as well as things from popular culture, such as lines from very famous TV shows or movies.

- Be careful with allusions. You have to know your audience well to use them. Sometimes, a style that is rich in allusions is used to “keep the rabble out”—that is, to make those who don’t “get” the allusions feel excluded.

- Making the choice to use allusions is all about audience knowledge. In American English culture, we don’t use many allusions, or depend on them much for communication. But in some cultures, such as many African tribes, almost every sentence is an allusion to an existing text or memorized maxim that is commonly known in the community. This is also true for many Arabic-language cultures, as well as many cultures in Asia.

Repetition

Does it bother you to see a thousand trees repeated in a forest? Probably not. A tree is repeated a thousand times, but there is enough variation to keep it beautiful. Something similar to this can be seen in writing. One does well to repeat one's argument in a number of forms, so that the audience's various capabilities are engaged.

People learn in different ways. Some like a story. Some like a clear statement of fact backed up by research. Repeating the same argument in different forms is an effective way to convey meaning, just as judiciously repeating a word keeps it lodged in the mind of the audience. Take a look at how Browning uses the word “smile” here in “My last duchess,” for an example of repeating something for effect:

Oh, sir, she smiled, no doubt,

Whene’er I passed her; but who passed without

Much the same smile? This grew; I gave commands;

Then all smiles stopped together.

Style, final thoughts

Respectfulness

Your tone, in general, should be calm, moderate, and generous, unless some circumstances of the writing situation demand otherwise. You should not call your supervisor “dude,” or anything casual or slangy. You should err on the side of formality in business situations, unless you know something more casual is acceptable.

How to work on your style

The best way to work on your style is by reading other writers and by doing imitation exercises using their work.

Take the example of a musician. He does not play his own music, usually. He plays a lot of music he likes, and then over time, his style becomes a sort of blend of all the different music he has played and listened to over the years. All good writers read a lot, and this influences their style.

Good writers also find the styles of writers they like, and imitate them, borrowing from them, pretending to be them, until their own unique style gets more developed. By modeling yourself on other writers, you can also expand your capabilities. For example, do you usually write very short sentences, so that you sound almost elementary? Don’t be afraid to keep writing like this. Many of the best writers do. But if you want to have the ability to write long sentences as well, try imitating something.