1.8: William Wordsworth

- Page ID

- 138843

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

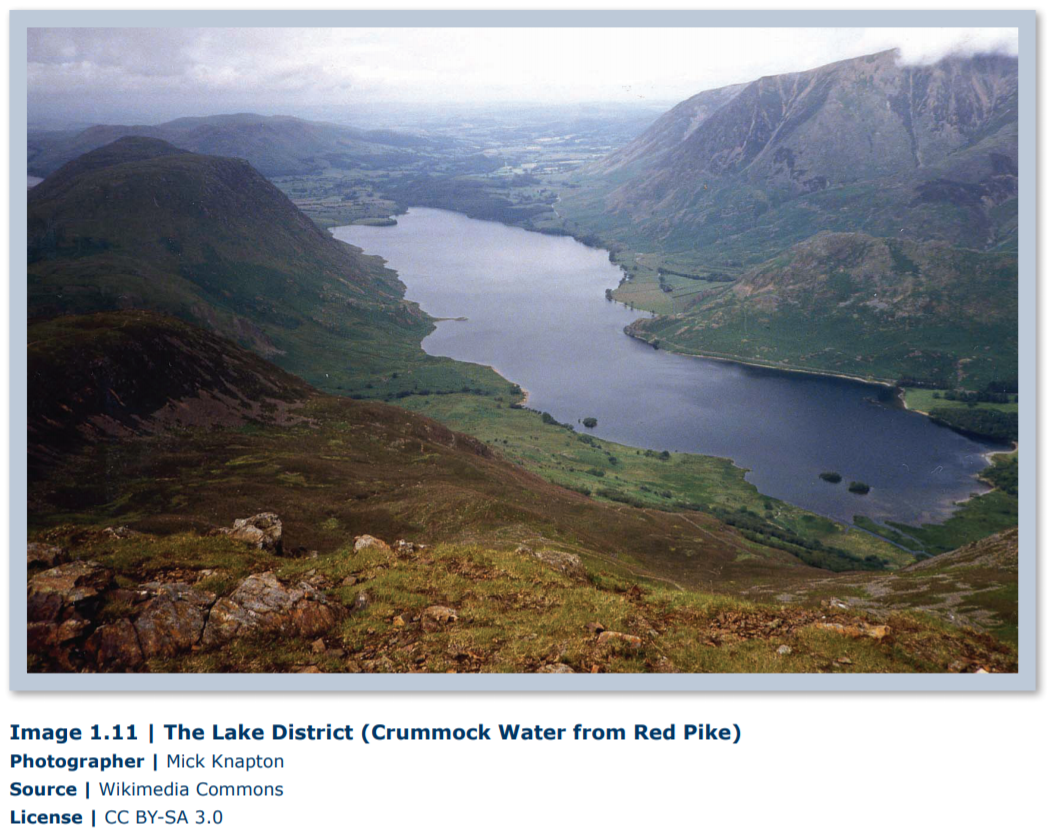

Unlike Blake, William Wordsworth was born into the upper middle to upper class. When he was orphaned in 1778, he was cared for by his aunt and uncle. He studied at Hawkshead Grammar School, near Windermere in the Lake District. His formal education ended with a short term at St. John’s College, Cambridge. But from his early childhood, Nature was his teacher; human nature was his subject.

In 1791, Wordsworth traveled to France to learn the French language, with an eye to making a living as a tutor in French. He became caught up in the French Revolution and had an affair with Annette Vallon, who bore him a daughter, Caroline, in 1792. His personal relationship with Annette Vallon turned just as the revolution did, in that Annette was a monarchist. Pro-revolutionary as he was, Wordsworth became afraid for his life, and as he could not make a living in France, he returned to England, effectively abandoning Annette Vallon and their daughter.

The Reign of Terror made it impossible for him to return to them until 1802, at which time he reached an agreement with Annette Vallon before marrying Mary Hutchinson. An inheritance made him financially independent, and he set up house in his beloved Lake District with his wife, his sister Dorothy, and his growing family. This contentment was earned at great emotional price, though. After leaving France and Annette Vallon, Wordsworth suffered a sort of nervous or emotional breakdown. And the crisis of that time—and indeed for the rest of his life—was his desire to recover his original self, to let “the child be father to the man” (“My Heart Leaps Up”).

In his poetry, Wordsworth tries to understand the human mind, especially during intense moments or states of excitement. All humans, regardless of class, experience emotions; and Wordsworth believed that in states of excitement, humans reach a level of dignity, power, and authenticity that is poetic. He described this revolutionary view not only of poetry but also of humanity in his Preface to the Lyrical Ballads, a collection of poems co-authored with his friend Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

This Preface declared a revolt against the poetry that went before. Wordsworth’s poetry would use the real language spoken by real men. He defines good poetry as the “spontaneous overflow of powerful emotions recollected in tranquility.” Spontaneity secures sincerity, transparency, and naturalness. Overflow secures power and strength of emotion. Recollection in tranquility secures truth and authenticity. The subject of his poetry was incidents and situations from common life. The language of his poetry was that which was really used by men. Over both this language and these incidents, Wordsworth throws the coloring of the imagination which makes common things uncommon, makes natural things seem supernatural. He thereby highlights the power of the imagination—that all humans possess and share equally.

“Strange Fits of Passion Have I Known”

Strange fits of passion I have known,

And I will dare to tell,

But in the lover’s ear alone,

What once to me befel.

When she I lov’d, was strong and gay

And like a rose in June,

I to her cottage bent my way,

Beneath the evening moon.

Upon the moon I fix’d my eye,

All over the wide lea;

My horse trudg’d on, and we drew nigh

Those paths so dear to me.

And now we reach’d the orchard plot,

And, as we climb’d the hill,

Towards the roof of Lucy’s cot

The moon descended still.

In one of those sweet dreams I slept,

Kind Nature’s gentlest boon!

And, all the while, my eyes I kept

On the descending moon.

My horse mov’d on; hoof after hoof

He rais’d and never stopp’d:

When down behind the cottage roof

At once the planet dropp’d.

What fond and wayward thoughts will slide

Into a Lover’s head—

“O mercy!” to myself I cried,

“If Lucy should be dead!”

“She Dwelt Among Untrodden Ways”

She dwelt among the untrodden ways

Beside the springs of Dove,

A Maid whom there were none to praise,

And very few to love.

A Violet by a mossy stone

Half-hidden from the eye!

—Fair as a star, when only one

Is shining in the sky.

She lived unknown, and few could know

When Lucy ceased to be;

But she is in her Grave, and, oh,

The difference to me!

“I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud”

I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o’er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host of golden daffodils:

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

Continuous as the stars that shine

And twinkle on the milky way,

They stretched in never-ending line

Along the margin of a bay:

Ten thousand saw I at a glance,

Tossing their heads in sprightly dance.

The waves beside them danced, but they

Outdid the sparkling waves in glee:—

A poet could not but be gay

In such a jocund company;

I gazed—and gazed—but little thought

What wealth the show to me had brought.

For oft, when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude;

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

“Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Immortality”

My heart leaps up when I behold

A rainbow in the sky:

So was it when my life began;

So is it now I am a man;

So be it when I shall grow old,

Or let me die!

The Child is father of the Man;

I could wish my days to be

Bound each to each by natural piety.

Wordsworth, “My Heart Leaps Up”

I

There was a time when meadow, grove, and stream,

The earth, and every common sight,

To me did seem

Apparelled in celestial light,

The glory and the freshness of a dream.

It is not now as it hath been of yore;—

Turn wheresoe’er I may,

By night or day,

The things which I have seen I now can see no more.

II

The Rainbow comes and goes,

And lovely is the Rose,

The Moon doth with delight

Look round her when the heavens are bare;

Waters on a starry night

Are beautiful and fair;

The sunshine is a glorious birth;

But yet I know, where’er I go,

That there hath past away a glory from the earth.

III

Now, while the birds thus sing a joyous song,

And while the young lambs bound

As to the tabor’s sound,

To me alone there came a thought of grief:

A timely utterance gave that thought relief,

And I again am strong:

The cataracts blow their trumpets from the steep;

No more shall grief of mine the season wrong; I hear the

Echoes through the mountains throng,

The Winds come to me from the fields of sleep,

And all the earth is gay;

Land and sea

Give themselves up to jollity,

And with the heart of May

Doth every Beast keep holiday;—

Thou Child of Joy,

Shout round me, let me hear thy shouts, thou happy

Shepherd-boy!

IV

Ye blessed Creatures, I have heard the call

Ye to each other make; I see

The heavens laugh with you in your jubilee;

My heart is at your festival,

My head hath its coronal,

The fulness of your bliss, I feel— I feel it all.

Oh evil day! if I were sullen

While the Earth herself is adorning,

This sweet May-morning,

And the Children are culling

On every side,

In a thousand valleys far and wide,

Fresh flowers; while the sun shines warm,

And the Babe leaps up on his Mother’s arm:—

I hear, I hear, with joy I hear!

— But there’s a Tree, of many, one,

A single Field which I have looked upon,

Both of them speak of something that is gone:

The Pansy at my feet

Doth the same tale repeat:

Whither is fled the visionary gleam?

Where is it now, the glory and the dream?

V

Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting:

The Soul that rises with us, our life’s Star,

Hath had elsewhere its setting,

And cometh from afar:

Not in entire forgetfulness,

And not in utter nakedness,

But trailing clouds of glory do we come

From God, who is our home:

Heaven lies about us in our infancy!

Shades of the prison-house begin to close

Upon the growing Boy,

But He beholds the light, and whence it flows,

He sees it in his joy;

The Youth, who daily farther from the east

Must travel, still is Nature’s Priest,

And by the vision splendid

Is on his way attended;

At length the Man perceives it die away,

And fade into the light of common day.

VI

Earth fills her lap with pleasures of her own;

Yearnings she hath in her own natural kind,

And, even with something of a Mother’s mind,

And no unworthy aim,

The homely Nurse doth all she can

To make her Foster-child, her Inmate Man,

Forget the glories he hath known,

And that imperial palace whence he came.

VII

Behold the Child among his new-born blisses, A six years’

Darling of a pigmy size!

See, where ‘mid work of his own hand he lies,

Fretted by sallies of his mother’s kisses,

With light upon him from his father’s eyes!

See, at his feet, some little plan or chart,

Some fragment from his dream of human life,

Shaped by himself with newly-learned art;

A wedding or a festival,

A mourning or a funeral;

And this hath now his heart,

And unto this he frames his song:

Then will he fit his tongue

To dialogues of business, love, or strife;

But it will not be long

Ere this be thrown aside,

And with new joy and pride

The little Actor cons another part;

Filling from time to time his “humorous stage”

With all the Persons, down to palsied Age,

That Life brings with her in her equipage;

As if his whole vocation

Were endless imitation.

VIII

Thou, whose exterior semblance doth belie

Thy Soul’s immensity;

Thou best Philosopher, who yet dost keep

Thy heritage, thou Eye among the blind,

That, deaf and silent, read’st the eternal deep,

Haunted for ever by the eternal mind, —

Mighty Prophet! Seer blest!

On whom those truths do rest,

Which we are toiling all our lives to find,

In darkness lost, the darkness of the grave;

Thou, over whom thy Immortality

Broods like the Day, a Master o’er a Slave,

A Presence which is not to be put by;

To whom the grave

Is but a lonely bed without the sense or sight

Of day or the warm light,

A place of thought where we in waiting lie;

Thou little Child, yet glorious in the might

Of heaven-born freedom on thy being’s height,

Why with such earnest pains dost thou provoke

The years to bring the inevitable yoke,

Thus blindly with thy blessedness at strife?

Full soon thy Soul shall have her earthly freight,

And custom lie upon thee with a weight,

Heavy as frost, and deep almost as life!

IX

O joy! that in our embers

Is something that doth live,

That nature yet remembers What was so fugitive!

The thought of our past years in me doth breed

Perpetual benediction: not indeed

For that which is most worthy to be blest;

Delight and liberty, the simple creed

Of Childhood, whether busy or at rest,

With new-fledged hope still fluttering in his breast: —

Not for these I raise

The song of thanks and praise;

But for those obstinate questionings

Of sense and outward things,

Fallings from us, vanishings;

Blank misgivings of a Creature

Moving about in worlds not realised,

High instincts before which our mortal Nature

Did tremble like a guilty Thing surprised:

But for those first affections,

Those shadowy recollections,

Which, be they what they may,

Are yet the fountain-light of all our day,

Are yet a master-light of all our seeing;

Uphold us, cherish, and have power to make

Our noisy years seem moments in the being

Of the eternal Silence: truths that wake,

To perish never;

Which neither listlessness, nor mad endeavor,

Nor Man nor Boy,

Nor all that is at enmity with joy,

Can utterly abolish or destroy!

Hence in a season of calm weather

Though inland far we be,

Our Souls have sight of that immortal sea

Which brought us hither,

Can in a moment travel thither,

And see the Children sport upon the shore,

And hear the mighty waters rolling evermore.

X

Then sing, ye Birds, sing, sing a joyous song!

And let the young Lambs bound

As to the tabor’s sound!

We in thought will join your throng,

Ye that pipe and ye that play,

Ye that through your hearts today

Feel the gladness of the May!

What though the radiance which was once so bright

Be now for ever taken from my sight,

Though nothing can bring back the hour

Of splendour in the grass, of glory in the flower;

We will grieve not, rather find

Strength in what remains behind;

In the primal sympathy

Which having been must ever be;

In the soothing thoughts that spring

Out of human suffering;

In the faith that looks through death,

In years that bring the philosophic mind.

XI

And O, ye Fountains, Meadows, Hills, and Groves,

Forebode not any severing of our loves!

Yet in my heart of hearts I feel your might;

I only have relinquished one delight

To live beneath your more habitual sway.

I love the Brooks which down their channels fret,

Even more than when I tripped lightly as they;

The innocent brightness of a new-born Day

Is lovely yet;

The Clouds that gather round the setting sun

Do take a sober colouring from an eye

That hath kept watch o’er man’s mortality;

Another race hath been, and other palms are won.

Thanks to the human heart by which we live,

Thanks to its tenderness, its joys, and fears,

To me the meanest flower that blows can give

Thoughts that do often lie too deep for tears.