8.3: Expertise and authorship

- Page ID

- 186013

By now you understand that a "good" source is credible, and that one of the things that makes something credible is having a credible author. You likely also understand that a credible author is someone who is an expert in the field that they are writing about. But how do you define "expertise"?

Take a moment and think of three or four people you might consider "experts." Now think about why you decided those people were experts.

Expertise is subjective, meaning based on personal feelings, opinions, or experiences. In short, expertise is left up to the eye of the beholder. Here are some examples:

For many people, one of the defining factors is education level. You definitely want a lawyer who went to an accredited law school and passed the bar. Similarly, you assume a doctor gives expert advice because they have a degree in medicine, passed the right exams, and are board-certified. You might even think that a doctor who has been practicing for 20 years is a better doctor, or more of an expert, than someone who just graduated. So that is an expert, right?

But what if expertise could be defined several different ways? Isn't a star athlete or prima ballerina an expert in their field? They may not have a formal degree, but are likely to be highly trained.

Skim this article by Fernand Gobet and Morgan Ereku on defining expertise(opens in new window) which challenges the idea that years of experience or education are the only ways to obtain expertise on a topic. Ultimately, it concludes that an expert is "somebody who obtains results that are vastly superior to those obtained by the majority of the population.” This may be a great definition when talking about experts, but it doesn't help too much in defining who is an expert we can trust and who isn't.

Often the key is context. What it takes to be an expert or authority on a topic really depends on the topic! If you want an expert on dancing, you are likely going to seek out an experienced, professional dancer. If you want medical advice, you are likely going to seek out a doctor (or google your symptoms, freak out, then seek a doctor who will tell you that it is a sore throat, not cancer). You would likely not ask the doctor to be an expert on the latest dance moves (unless they were moonlighting as a ballroom champion). Neither would you quote a lawyer on how hot air balloons work.

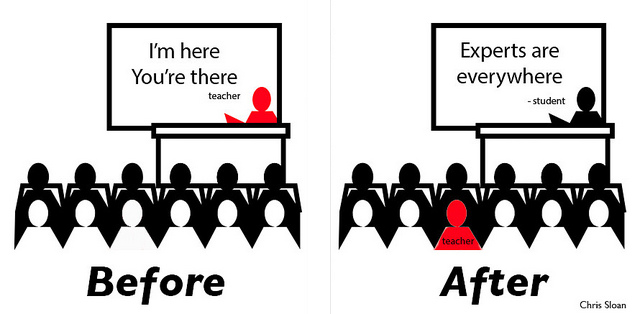

I (your instructor) bring expertise about critical thinking and academic research to our classroom. You bring expertise to our classroom, too, about other topics and disciplines.

"The fool doth think he is wise, but the wise man knows himself to be a fool."

- William Shakespeare

Overconfidence isn't expertise. Sometimes, people will believe themselves to be experts when they don't actually have the expertise that the general public would want in order to think of them as an authority on the subject. They may or may not have good research, but they may not have the expertise to tell the difference. A good example might be a mother who believes that they are an expert on a medical condition that their child has, when in reality they are experts on their own child's experience. They may actually gain the knowledge and expertise of an authority through educating themselves intensely, but proximity alone does not give expertise.

Check out this video from McMaster Libraries on authority & expertise.

Different ideas/beliefs doesn't mean lack of expertise in others. Another issue is that sometimes people disagree about whether or not someone is an expert. Sometimes people dismiss the expertise of people presenting ideas that are contrary to their current beliefs, simply because it doesn't match up with what they think it should be. People also tend to accept information without question that lines up with their way of thinking. This is called confirmation bias (opens in new window)and is something everyone does, even when aware of the phenomenon.

Always remember that as a researcher you are looking for facts, not information that agrees with your opinion! Of course, your opinion might align with the facts, but practice removing your opinion from the equation when you research.

Take a few minutes and think about your topic. How would you define an expert in that field? What sorts of credentials, experience, ability, or education would you want your experts to have? Do you have an opinion on your topic? Can you separate your opinion from your research?

Image credit: Chris Sloan(opens in new window)