2.4: The Art of Rhetoric

- Page ID

- 20612

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)What is Rhetoric?

In its simplest form, RHETORIC is the art of persuasion. Every time we write, we engage in debate or argument. Through writing and speaking, we try to persuade and influence our readers, either directly or indirectly. We work to get them to change their minds, to do something, or to begin thinking in new ways. Put simply, to be effective, every writer needs to know, and be able to use, principles of rhetoric.

Writing is about making choices, and knowing the principles of rhetoric allows a writer to make informed choices about various aspects of the writing process. Every act of writing takes place in a specific RHETORICAL SITUATION, which is a situation or circumstance in which someone (a writer or speaker) must persuade an audience to do something, to change their minds, to influence them, etc. This "rhetorical situation" is the same concept that L. Lennie Erwin terms "the writing situation" in his discussion on how writing is different from speaking (see "The Difference between Speaking and Writing").

The three most basic, yet important components of a rhetorical situation are:

- The purpose of writing or rhetorical aim (the goal the writer is trying to achieve or argument the writer is trying to make)

- The intended audience

- The writer/speaker

These three elements of the rhetorical situation are in a constant and dynamic interrelation. All three are also necessary for communication through writing (or speaking) to take place. For example, if the writer is taken out of this equation, the text will not be created. Similarly, eliminating the text itself will leave the reader and writer, but without any means of conveying ideas between them, and so on.

Other components of the rhetorical situation include:

- the medium (the form of communication)

- the allotted time for the message (how much time does writer have? appropriate time to persuade?)

- the political, social, or cultural implications, place, etc.

All writing (or speaking) that is persuasive comes from a source of urgency or EXIGENCE –– a need to communicate the message.

NOTE

Please note that the term “rhetoric” also is used to mean someone speaking bombastic thoughts that are empty of meaning. The online Oxford dictionary defines rhetoric also as “language designed to have a persuasive or impressive effect on its audience, but often regarded as lacking in sincerity or meaningful content” and the example they give is, “all we have from the Opposition is empty rhetoric.” Such a meaning is unfortunately derived from the emphasis of rhetoric on presentation and delivery. In this course, we will focus on rhetoric as a means of effective communication as we aspire to become skilled rhetoricians ourselves.

The following video focuses on the use of rhetoric from the viewpoint as a writer. As you watch, consider how the same elements hold true from the viewpoint of a reader.

The Rhetorical Situation

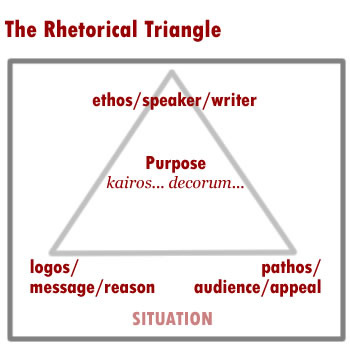

When composing an essay, every writer must take into account the conditions under which the writing is produced and will be read. It is customary to represent the three key elements of the rhetorical situation as a triangle of writer, reader, and text, or, as they are represented on this image, as "communicator," "audience," and "message."

Figure 2.4.1: The Rhetorical Triangle

Source: St. Edward's University

Changing the characteristics of any of the elements depicted in the figure above will change the other elements as well. For example, with a change in the beliefs and values of the audience, the message will also change to accommodate those new beliefs.

What does this understanding of rhetoric have to do with academic and research writing? Everything, really. If you have ever had trouble with a writing assignment, chances are it was because you could not figure out the assignment’s purpose. Or perhaps you did not understand very well who was your reader. It is hard to commit to purposeless writing done for no one in particular, which is how many students incorrectly approach academic writing.

Rhetorical Appeals

In order to persuade their readers, writers must use three types of proofs, or rhetorical appeals. They are logos, or logical appeal; pathos, or emotional appeal; and ethos, or ethical appeal, or appeal based on the character and credibility of the author. An additional appeal, called kairos, refers to whether a message is "of its time period." It is easy to notice that modern words “logical,” “pathetic,” and “ethical” are derived from those Greek words. In his work Rhetoric, Aristotle writes that the three appeals must be used together in every piece of persuasive discourse. An argument based on the appeal to logic, or emotions alone will not be an effective one.

Pathos

Pathos can best be described as the use of emotional appeal to sway another's opinion in a rhetorical argument. Emotion itself should require no definition, but it should be noted that effective 'pathetic' appeal (the use of pathos) is often used in ways that can cause anger or sorrow in the minds and hearts of the audience.

Pathos is often the rhetorical vehicle of public service announcements. A number of anti-smoking and passive smoking related commercials use pathos heavily. One of the more memorable videos shows an elderly man rising from the couch to meet his young grandson who, followed by his mother, is taking his first steps toward the grandfather. As the old man coaxes the young child forward, the grandfather begins to disappear. As the child walks through him the mother says "I wish your grandpa could see you now." The audience is left to assume that the grandfather has died, as the voice-over informs us that cigarette smoke kills so many people a year, with a closing statement, "be there for the ones you love." This commercial uses powerful words (like "love") and images to get at the emotions of the viewer, encouraging them to quit smoking. The goal is for the audience to become so "enlightened" and emotionally moved that the smoking viewers will never touch another cigarette.

Ethos

Ethos can be seen as the credibility that authors, writers, and speakers have when they present themselves in front of an audience. If, on the first day of class, your professor walked in, kind of bent over and looking like they had been out all night and picking their nose, how would you perceive that instructor? What would your view of the class he takes be? How confident would you be that this person knows what they are talking about?

Ethos encompasses a large number of different things which can include what a person wears, says, the words they use, their tone of voice, their credentials, their experience, their relationship with the audience, verbal and nonverbal behavior, criminal records, etc. At times, it can be as important to know who the person presenting the material is, as what they are saying about a topic.

Many companies, especially those big enough to afford famous spokespeople, will use celebrities in their ad campaigns to promote the sale of their products. Certain soft drink companies have used the likes of Ray Charles, Madonna, and Britney Spears to sell their products, and have been successful in doing so. The thing you need to ask yourself is: what do these celebrities add to the product other than their fame? Or is it their relationship with the audience that is the selling point?

Often times ads for medical products or even chewing gum might say that four out of five doctors/dentists recommend a certain product. Some commercials may even show a doctor in a white lab coat approving whatever is for sale. Now, provided that the person you are viewing is an actual doctor, this might be an example of a good ethos argument. On the other hand, if an automotive company uses a famous sports figure to endorse a product, we might wonder what that person knows about this product. The campaign and celebrity are not being used to inform the consumer, but rather to catch their attention with what is actually a faulty example of ethos.

How does this apply to writing? To begin, if you are going to cite an article about racial equality published by the Ku Klux Klan, or a Neo-Nazi organization, this might send up a red flag that this particular article might be written from a biased viewpoint. You need to research an author's background to re-assure yourself that what they are writing is unbiased. Also, if you are trying to present a formal project, you may want to increase your positive ethos by using appropriate terminology. Writing that "abortions are all whack and stuff" is probably not the best way to convince your audience of your point of view. It may happen that you as a writer adopt different voices for different assignments, but your word choice and your approach to the assignment should reflect what it is you want to say.

Logos

Logos is most easily defined as the logical appeal of an argument. Say that you are writing a paper on COVID-19 and you say "COVID-19 is just like the flu, so we should take the same measures as the flu." This statement is illogical because the virus itself, it's characteristics, and the overall situation is not like that of the flu. The statement has an illogical comparison. The COVID-19 virus is in a different family of viruses (corona viruses) than are the various influenza viruses, such as H1N1. COVID-19 displays a wide variety of symptoms (or no symptoms) and is much more contagious precisely because it can be transmitted without any symptoms. In addition, we have immunizations against the flu virus, which we do not yet have for the COVID-19 virus.

Kairos

"Kairos" is an important, but sometimes illusive, rhetorical term. The word itself means "time," and time is central to the concept, which means the "right time" or the "ideal moment" for communicating. Kairos is basically about the context of the moment: what's relevant to the audience at any particular time? Some rhetoricians describe kairos as a fourth "appeal" because rhetors frequently appeal to the urgency of a particular time or moment to engage an audience.

Timing, as they sometimes say, is everything. Rhetoric is about finding the best "available means" of persuasion "at any given moment" or "in any given case." Past, present, and future ("forensic," "epideictic," and "demonstrative" as the video, below, on labels them) are definitely part of the picture here, as well.

Video: How to use rhetoric to get what you want by Camille A. Langston. All Rights Reserved. Standard YouTube license.

Summary: Chart

The chart below summarizes the key points relating to the rhetorical appeals:

Rhetorical Appeal |

Abbreviated Definition |

Reflective Questions |

|

Appeal to credibility You may want to think of ethos as related to "ethics," or the moral principles of the writer: ethos is the author's way of establishing trust with his or her reader. |

|

|

|

Appeal to emotion You may want to think of pathos as "empathy," which pertains to the experience of or sensitivity toward emotion. |

|

|

|

Appeal to logic You may want to think of logos as "logic," because |

|

|

|

Appeal to timeliness You may want to think of kairos as the type of persuasion that pertains to "the right place and the right time." |

|

How the Appeals Work Together to Persuade

Understanding how logos, pathos, and ethos should work together is very important for writers who use research. Often, research writing assignments are written in a way that seems to emphasize logical proofs over emotional or ethical ones. Such logical proofs in research papers typically consist of factual information, statistics, examples, and other similar evidence. According to this view, writers of academic papers need to be unbiased and objective, and using logical proofs will help them to be that way.

Because of this emphasis on logical proofs, you may be less familiar with the kinds of pathetic and ethical proofs available to you. Pathetic appeals, or appeals to emotions of the audience were considered by ancient rhetoricians as important as logical proofs. Yet, writers are sometimes not easily convinced to use pathetic appeals in their writing. As modern rhetoricians and authors of the influential book Classical Rhetoric for the Modern Student (1998), Edward P.J. Corbett and Robert Connors said, “People are rather sheepish about acknowledging that their opinions can be affected by their emotions” (86). According to Corbett, many of us think that there may be something wrong about using emotions in argument. But, I agree with Connors, pathetic proofs are not only admissible in argument, but necessary (86-89). The most basic way of evoking appropriate emotional responses in your audience, according to Corbett, is the use of vivid descriptions (94). This is demonstrated at the beginning of many newspaper and magazine feature articles.

Using ethical appeals, or appeals based on the character of the writer, involves establishing and maintaining your credibility in the eyes of your readers. In other words, when writing, think about how you are presenting yourself to your audience. Do you give your readers enough reasons to trust you and your argument, or do you give them reasons to doubt your authority and your credibility? Consider all the times when your decision about the merits of a given argument was affected by the person or people making the argument. For example, when watching television news, are you predisposed against certain cable networks and more inclined toward others because you trust them more?

So, how can writers establish credible personas for their audiences? One way to do that is through external research. Conducting research and using it well in your writing help you with the factual proofs (logos), but it also shows your readers that you, as the author, have done your homework and know what you are talking about. This knowledge, the sense of your authority that using logos creates among your readers, will help you be a more effective writer.

The logical, pathetic, and ethical appeals work in a dynamic combination with one another. It is sometimes hard to separate one kind of proof from another and the methods by which the writer achieves the desired rhetorical effect. If your research contains data that is likely to cause your readers to be emotional, it can enhance the pathetic aspect of your argument. The key to using the three appeals is to use them in combination with each other and in moderation. It is impossible to construct a successful argument by relying too much on one or two appeals while neglecting the others.

Using Rhetorical Appeals in Your Own Writing

Identifying these appeals in persuasive writing is a valuable skill to learn; understanding how to use these appeals in your persuasive writing can prove to be an even more powerful ability to develop. To begin, several ways to appeal to logic exist. Consider the structure and quality of your argument. Digital strategist and rhetorician, Daniel T. Richards, asks writers to consider these questions: “Does your conclusion follow from your premises? Will your audience be able to follow the progression? Does your argument provide sufficient evidence for your audience to be convinced?” To improve the quality of your argument, consider:

- Referring to facts and figures.

- Citing relevant, current statistics.

- Providing examples.

- Including and addressing an opposing view.

- Using visual representations.

In addition, as Lane, McKee, and McIntyre recommend in their article regarding logos: maintain consistency in your argument, and avoid fallacious, or faulty, appeals to logic. For example, in “Fallacious Logos,” they provide an overview of several false appeals to logic, including the false dilemma, which assumes that there are only two options when there are more.

Writers may employ several methods to appeal to pathos. Read “Pathos” to explore several suggestions which include:

- Referring to other emotionally compelling stories.

- Citing stark, startling statistics that will invoke a specific emotion in audience members.

- Showing empathy and/or understanding for an opposing view.

- Using humor, if appropriate.

However, in your efforts to appeal to the audience’s emotions, avoid relying on faulty appeals. For example, “Fallacious Pathos” points out that using emotional words that evidence does not support leads to the argument by emotive language fallacy.

In pondering how to effectively employ rhetorical devices and aptly avoid fallacies, writers tend to miss the relationship among the rhetorical appeals. Consequently, there is something very right about such arguments as the one advanced by Richards, who argues that “your argument could be sound. It could even be emotionally compelling. But if your audience doesn’t trust you, if they don’t think you have their interest at heart, it won’t matter” (“The 3 Rhetorical Appeals”). Enhance the effectiveness of appeals to pathos and logos with appeals to ethos.

To demonstrate your credibility, try:

- Referring to relevant work and/or life experience.

- Citing your relevant awards, certificates, and/or degrees.

- Providing evidence from relevant, current, and credible sources.

- Carefully proofreading your work, and asking a few other people to so as well.

Additionally, follow McKee and McIntyre’s advice in “Fallacious Ethos.” McKee and McIntyre provide specific examples of fallacious ethos.

Conversely, appeals to kairos can help you make use of the particular moment (Pantelides, McIntyre, and McKee). Ask yourself if you can capitalize on any of the audience’s fast-approaching moments to create a sense of urgency. However, avoid false appeals to kairos. Read “Fallacious Appeals to Kairos” to learn more about this topic.

Good writers write to win. As such, rhetorical appeals underlie much of the successful persuasive writing in society, whether in the form of written arguments, television commercials, or educational campaigns. As previously discussed, some thoughtful, strategic anti-smoking campaigns have reduced smoking-related diseases and death. Additionally, Ariel Chernin, advertising researcher, observes that a large body of literature proves that food marketing affects children’s food preferences. Similarly, appealing to logos, pathos, ethos, and kairos in your persuasive writing can help you achieve your goals. Approaching rhetorical appeals from the inside out—from the perspective of the writer—one can note their effectiveness in persuasive writing, and one can write to win.

Contributors

- Adapted from What is Rhetoric by WikiBooks, CC-BY-SA

- Adapted from Methods of Discovery by Pavel Zemliansky, provided by Three Rivers Digication, CC-NC-SA 3.0.

- Adapted from The Writing Commons. byThe Writing Commons, CC-NC-ND

- Adapted from RhetPrimer by Alissa Messer, CC-BY-SA

This page most recently updated on June 5, 2020.