13.7.10: Spain in the 15th and 16th centuries- Renaissance

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 88729

Expeditions to the Americas, and the often destructive colonization and evangelization that followed, helped the Spanish monarchs to amass a great fortune based on indigenous labor and natural resources.

1400–1600

The Renaissance in Spain

We often think of globalization as a modern phenomenon, but the confluence of cultures we see today was already growing in the Spanish Empire during the 15th and 16th centuries. For instance, dividing screens from Japan were imported to Mexico, where they were used in colonial Spanish homes. Chocolate and tomatoes from Mexico and Central America made their way to Spain, where they enlivened the cooking of royal chefs. Spain, with its territory reaching from Europe to the Philippines, soon amassed a huge amount of wealth, and consequently became not only a center for art patronage (the commissioning of artworks), but also a place where imported materials, goods and ideas fostered new approaches to art.

Diversity and dominance

For much of the Middle Ages, Spain had been home to three dominant religions: Islam, Christianity, and Judaism. The convivencia, or coexistence, of these groups characterized Spain during this period. The coexistence ultimately ended in 1492, when the Catholic monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella of Castile toppled the last Muslim stronghold in Granada and expelled the Jews from the Iberian Peninsula. However, many Muslims and Jews remained and were converted (some forcibly) to Christianity, at which point they became known as moriscos and conversos.

Ferdinand and Isabella also established the Inquisition, a Catholic institution whose job it was to root out heresy. The officials responsible were highly suspicious of the newly converted, and numerous records attest to the persecutions, imprisonments, and occasional burnings undertaken by the Inquisition. A painting by Pedro Berruguete shows an auto-da-fe (“act of faith”): a ceremony in which someone was accused and then punished by inquisitors. Despite these persecutions, moriscos and conversos retained elements of their previous practices and continued to contribute to the cosmopolitan nature of Spanish society.

1492 was also a remarkable year because it was the moment that Christopher Columbus discovered that the world was much larger than Europeans had previously believed. His expeditions to the Americas, and the often destructive colonization and evangelization that followed, helped the Spanish monarchs to amass a great fortune based on indigenous labor and natural resources. By the mid-sixteenth century, the Spanish controlled an impressive amount of land throughout the Americas, and large urban centers had been established in Peru, Mexico, and Hispaniola (today the Dominican Republic)—to name few—all the result of the conquest of local indigenous populations like the Inka and the Aztec. The Spanish viceroyalties eventually grew to encompass much of the Americas as well as the Philippines, making for a truly diverse and global empire.

Itinerant artists, traveling ideas

During the Renaissance, the Spanish empire also extended throughout Western Europe. The dominant ruling family during this time was that of the Hapsburgs, including the powerful Charles V, who became Holy Roman Emperor after the death of Ferdinand and Isabella in 1516, and was succeeded by his equally influential son Philip II in 1556. Given Spain’s political reach in Europe, it is not surprising that Spanish Renaissance art displays influences from Flanders and Italy. Artists from around Europe traveled to the Iberian Peninsula to seek favor with the Spanish court, and artworks flowing in from other parts of the empire influenced artists already working in Spain.

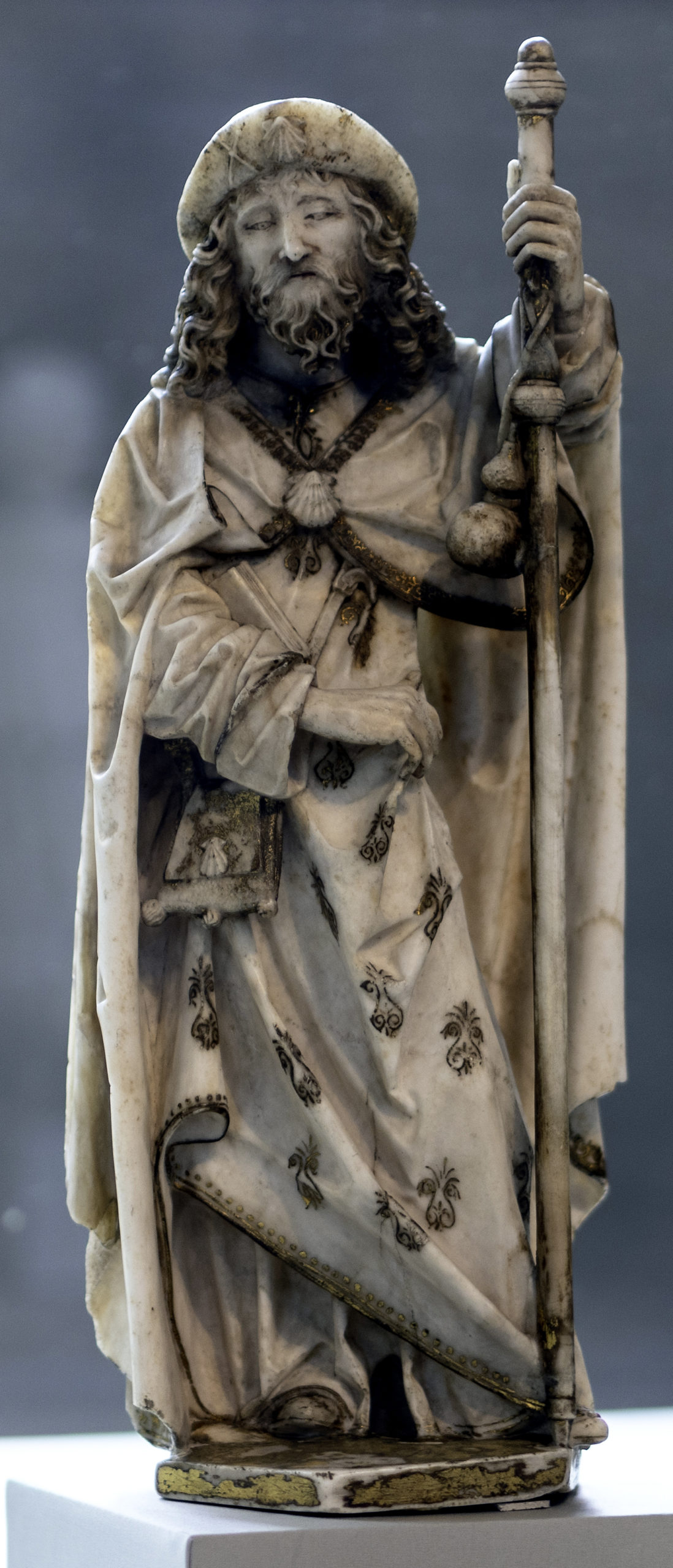

During the fifteenth century, prior to and during the reign of Ferdinand and Isabella, the influence of Flanders was felt most strongly. Artists like Bartolmé Bermejo and Fernando Gallego exemplify what is referred to as the Hispano-Flemish style, or the combination of Spanish and Flemish elements. In Bermejo’s Santo Domingo de Silos, for instance, the saint sits on an elaborate throne wearing golden robes executed in great detail. Like many Flemish paintings of this period, the work is a feast for the eyes with its ornateness, opulence, and attention to detail. The saint’s crumpled drapery also reveals Flemish influences.

Northern Renaissance paintings, tapestries, and other kinds of artworks bought by wealthy Spanish collectors also influenced art in Spain. Prints (for instance, engravings by Northern Renaissance artists such as Albrecht Dürer or Martin Schonguaer) circulated throughout Spain and influenced artists like Bermejo. Some of the most famous Flemish painters traveled to Spain or had their works collected by Spanish patrons. Jan van Eyck journeyed to the Iberian Peninsula in 1428-29. He and Rogier van der Weyden, and many other Flemish painters also regularly sent paintings to patrons in Spain. Spanish royalty collected many well-known paintings at this time (many of which are now on view in the Museo del Prado in Madrid), including Hieronymous Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights, Dürer’s 1498 Self Portrait, and Titian’s Bacchanal of the Andrians, which also influenced courtly tastes and the direction of Spanish art.

Italian artistic ideas and motifs are also noticeable in Spanish painting and sculpture. These influences can be seen in works like Berruguete’s Beheading of the Baptist from c. 1490 in the parish church of Santa Maria del Campo, in which the black-and-white tiled floor recedes into the background, creating illusionistic sense of space, complete with classicizing architectural elements—all of which are hallmarks of the Italian Renaissance. Nevertheless, the complex nature of Spanish art is simultaneously revealed in this painting, because it also includes “Hispano-Flemish” characteristics like the stylized drapery.

Other Italianate influences on Spanish art appear in the paintings of Joan de Joanes and Luis de Morales. Joanes was inspired by Raphael’s lyricism and gracefulness, and sometimes directly quoted from Raphael’s artworks. Luis de Morales painted multiple devotional paintings of Christ and the Virgin Mary, many of which show the artist’s adaptation of Leonardo da Vinci’s sfumato and Mannerist elements, including elongated bodies and faces. Spanish artists like the sculptor Alonso Berruguete (son of Pedro Berruguete) sometimes traveled to Italy for training, but many only encountered Italian art that was displayed in Spain or through prints or copies of Italian artworks.

The Court of Philip II

During the reign of Philip II in the later sixteenth century, Spanish art shifted away from the Hispano-Flemish mode that had been popular earlier. Philip II favored several artists, among them the revered Titian, who sent portraits of the Hapsburg ruler from his studio in Venice. Other court artists, including Alonso Sánchez de Coello and Sofonisba Anguissola, painted portraits of court members, fulfilling Philip II’s desire to visually represent the power of his imperial court. Philip II also sponsored the construction of the Escorial, an immense complex that comprises royal burials (including the body of Charles V), a royal chapel, and a seminary. The plan is rigidly geometrical, and is defined by a giant, symmetrically subdivided square. The classical entrance bay is drawn from Italian Renaissance architecture, and the tower-flanked façade borrows from the French chateau style. The overall impression is austere and foreboding—an expression of Philip II’s fervent religiosity and imperial power. On the interior, numerous artists, some hailing from Italy, were commissioned to produce paintings, frescoes, sculptures, and tapestries to adorn this monumental space.

Drama in wood

We typically associate materials like marble and bronze with Renaissance sculpture—not polychromed (multicolored) wood. Yet in Spain, painted and gilded (gold-covered) wooden sculpture was immensely popular, and sculptors who worked in wood, like Juan de Juni, Alonso Berruguete, and Diego de Pesquera, were well-known in their heyday. After the sculptor crafted the figures, typically another artist would paint the sculpture. This was often done using the time-consuming estofado technique, which involved layering gold or silver leaf onto the wood, then painting over it to create a brilliant surface. Sometimes the artist would remove layers of paint to reveal the metallic materials beneath.

In 1544, Juni completed his Burial of Christ for the lower level of an altarpiece. It is a large figural grouping, carved from wood and painted, and portraying six life-sized individuals grieving over Christ’s dead body on a sepulcher. These figures include Christ’s mother, John the Evangelist, Mary Magdalene, Mary Cleophas, Nicodemus, and Joseph of Arimathea. Though Juni originally hailed from Burgundy, France, here he created classicizing, naturalistic bodies that reflect the adaptation of Italian artistic trends.

A clash of beliefs

Even as Humanist ideas spread throughout Charles V’s Spain, the sixteenth century was also a time of religious controversy and reform. Catholicism found itself threatened by Protestantism, which had been taking hold in northern Europe since Martin Luther’s Reformation in the early decades of the century. In Spain, the Inquisition investigated groups thought to be unorthodox or subversive (such as the moriscos and conversos), including ones too closely aligned with Lutheran thinking.

Many of the artworks during the reign of Philip II responded to the Council of Trent, where Catholic officials re-emphasized the significant role that art could play in moving the faithful to piety—particularly in response to Protestant criticisms. Domenikos Theotokopoulos, better known as El Greco, is a key example of an artist who understood the power that images could have to move souls, and his emphatic religious work was welcomed in Spain.

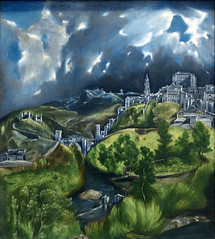

El Greco was trained on the Greek island of Crete, where he painted icons in the Byzantine tradition. He then traveled to Italy, where he absorbed the influences of Tintoretto and others before finding work in Toledo, Spain. El Greco’s The Savior provides a fitting end to this short essay on the artistic influences that shaped visual culture in Renaissance Spain. The painting not only displays the mannerist, mystical tendencies in Spanish art that were absorbed by this Cretan artist, but also speaks to the globalized Spanish Empire: the red glaze on Christ’s tunic comes from the crushed cochineal bug, acquired from Spain’s American colonies and exported to the Iberian Peninsula to be traded around the world. Renaissance Spain was truly eclectic.

Additional Resources:

Pedro Berruguete’s Auto da Fe Presided Over by Santo Domingo de Guzman at the Museo del Prado

Bartolomé Bermejo’s Saint Dominic of Silos enthroned as a Bishop at the Museo del Prado

Images of a Burgundian cope (cape worn by a priest)

Joan de Joanes’s The Burial of St. Stephen at the Museo del Prado

Luis de Morales, The Virgin Nursing the Child at the Museo del Prado

Juan de Juni’s Burial of Christ on Europeana

El Greco’s The Savior on Europeana

15th century

Fifteenth-century Spanish painting, an introduction

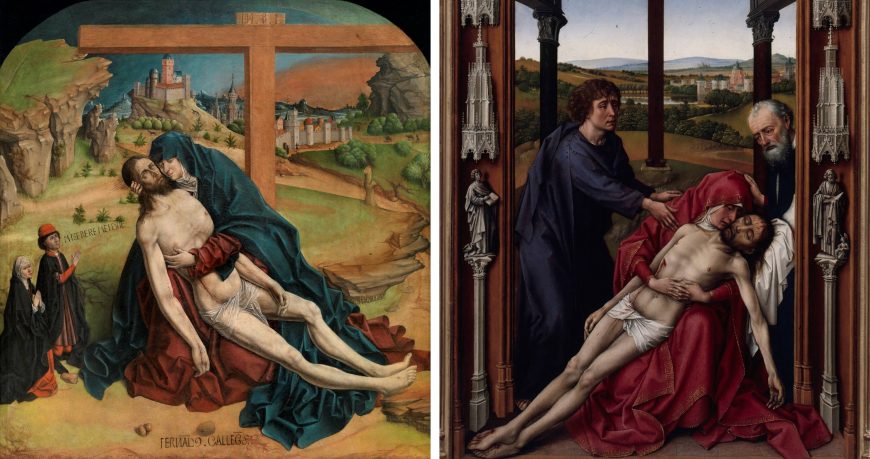

Mary sorrowfully embraces her dead son, his broken body resting across her lap. The cross rises behind them. In this piedad (often referred to with the Italian word Pietà — an image of Mary cradling the dead body of Christ), painted by the Spanish artist Fernando Gallego, the scene of mourning is set against a vast landscape filled with rocky crags rising from the earth, rolling hills, and a fortified medieval town that is supposed to be Jerusalem in the background. To the left of Mary and Jesus, two smaller figures kneel, most likely the painting’s patrons.

Trends in Spanish painting: looking to Northern Europe

Gallego was a Spanish artist who worked largely in the Kingdom of Castile in the latter half of the fifteenth century, and his painting is representative of important trends in fifteenth-century Spanish painting. It reveals Gallego’s interest in the Netherlandish (Northern Renaissance) visual idiom, which a great deal of Spanish artists did in the second half of the fifteenth century. His use of realistic details, crumpled drapery, angular bodies, and detailed landscape all parallel Netherlandish artists. Also, Gallego’s treatment of space, especially the empirical perspective we notice throughout the composition, suggests he drew upon northern visual modes.

Gallego likely adapted Rogier van der Weyden’s Pietà from the Miraflores Altar, which had belonged to King Juan II of Castile and then given to the Miraflores Charterhouse (near Burgos). However, Gallego did not slavishly copy van der Weyden’s painting (or another artist’s replica of it) nor Netherlandish painting techniques more generally. His color palette is more distinctly Spanish, with a greater use of yellows and browns. The less saturated and brilliant color palette is due to omitting the glazing so typical of northern painting. Gallego absorbed northern techniques and paired them with his own native ones, and was one of many Spanish artists who found inspiration and models in Netherlandish painting.

An increased internationalization occurred in the second half of the fifteenth century in the Spanish Kingdoms. Trade routes, political exchanges, and merchant activity all helped to foster greater dialogue among artists, among them Lluís Dalmau, Fernando Gallego, Bartolome Bermejo, Jacomart, Jaume Huguet, and Joan Reixac. In particular, many artists across the Spanish Kingdoms began to demonstrate a marked interest in the Netherlandish mode, revealing the influence of the ars nova (the new art — often used to describe the emerging naturalism of Renaissance art) on Spanish art.

Several reasons for this increased interest exist. First, there was a great influx of paintings, sculptures, tapestries, and other goods to Spain from Flanders. Such items were collected and displayed in homes or included in prominent collections. The second is the rapid spread of northern woodcuts and engravings, such as those by Martin Schongauer, after 1450. One of the first indications that Netherlandish art was transforming Spanish painting is found in contracts, where we find patrons asking for grisaille to be included in paintings (grisaille, or painting in grayscale, was common in Flanders).

In particular, the Kingdom of Castile and the Kingdom of Aragon borrowed models and styles from their northern counterparts, or had Netherlandish artists travel south to work in the Iberian Peninsula. Until the end of the fifteenth century, there were few classicizing influences and little visual interest in all’antica decoration, such as what we find throughout much of the Italian peninsula.

Trends in the Kingdom/Crown of Aragon

The taste for the Netherlandish visual mode was strong in the second half of the fifteenth century, although it had started earlier. King Alfonso the Magnanimous (King of Aragon, Valencia, Sicily, Majorca, Naples, Corsica, and Sardinia, and Count of Barcelona) displayed an early taste for northern art. In 1434, while in the Kingdom of Sicily, he requested Flemish tapestries from Flanders, and he owned paintings by Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden.

In the Kingdom of Aragon, beginning in the 1440s, painters turned more towards northern influences, moving away from the International Gothic style. Few painters, if any, seemed to travel to Flanders, although it is possible that undiscovered archival records will unearth some. One of the first artists from here who did travel north was Bartolome Bermejo in 1474. Netherlandish artists also settled in the Kingdom of Aragon, although not so many as to suggest they were the ones solely responsible for the popularity of a northern visual idiom.

Valencia and Lluís Dalmau

The Kingdom of Valencia (within the Kingdom/Crown of Aragon) was an especially important place for the Netherlandish visual idiom to take root and grow with Spanish artistic preferences. Some artists traveled north to Flanders. One of the earliest to do so was Lluís Dalmau, who was sent in 1431 by King Alfonso. Born and raised in Valencia, Dalmau had been trained in the International Style. In Flanders, he became acquainted with Netherlandish painting techniques and inventions, and he likely observed well-known artworks like the Ghent Altarpiece in St. Bavo’s Cathedral.

Dalmau returned to Spain, settling in Barcelona. One of the first paintings he completed upon his return was his famous Virgin of the Councillors in Barcelona (Catalonia was at this time part of the Crown of Aragon), which is one of the earliest paintings to exhibit the influences of Netherlandish painting. The painting was commissioned by the Barcelona City Council (Casa de la Ciutat) to hang in the chapel at the council palace.

It displays the Virgin and Child seated on an elaborate wooden throne, around whom are members of the city council, kneeling before her. Saints and angels stand behind them. Naturalistic details fill the entire painting. The council members are all portraits taken from life, and here they are shown on the same scale as the Virgin Mary. We also observe other characteristics of northern painting, such as elongated bodies and empirical perspective. Dalmau’s painting also clearly indicates the influence of Jan van Eyck, especially his Madonna and Child with Canon van der Paele and the angels from the Ghent Altarpiece in the Adoration of the Lamb panel.

Besides Dalmau, other Valencian artists, like Joan Pons and the Master of the Porciùncula, show a keen interest in northern techniques and visual idiom. As we see in the work of Van Eyck and other artists in Northern Europe, paintings are filled with a great deal of ornamentation, including gemstones and brocades.

Northern Renaissance artists also traveled to Spain, producing paintings for important Spanish patrons. Jan van Eyck traveled to the Crown of Aragon in 1427. Many Netherlandish artists would even make careers living and working in Spain. Flemish artists like Luis Alimbrot (Louis Allincbrood or Lodewijk Allyncbrood/Hallincbrood), who was in Bruges 1432–37, was active in Valencia 1439–60. His son, Jordi Alimbrot (Joris Allyncbrood), who was born in and worked in Bruges, also settled and worked in Valencia from 1463 onward.

Not all kingdoms of the Crown of Aragon displayed an early and heightened interest in northern visual modes. Majorca was late to illustrate such influences, only beginning to incorporate them in the 1480s (versus the 1440s in Valencia and 1450s in Catalonia).

The Crown of Castile and the patronage of Isabel of Castile

Netherlandish influence was perhaps strongest in the Kingdom of Castile. However, there is no individual artist, like Dalmau, to whom we credit the origins of such influences. In general, there are fewer named and signed works here, which makes it more challenging to assign this role to a specific artist. Still, we tend to think a Spanish painter with first-hand knowledge of Flemish painting worked in Castile, or perhaps even a Netherlandish artist who relocated there.

By the end of the fifteenth century, many prominent Netherlandish artists lived and worked in Castile, brought there by Queen Isabel of Castile, who adored Netherlandish-style paintings. Michael Sittow, Juan de Flandes, and Antonio Inglés were all foreign artists who came to work for Isabel, who also collected Flemish paintings by Deiric Bouts, Hans Memling, and van der Weyden. Among the immigrant artists at her court, the most famous was Juan de Flandes. He was even made court painter. Concurrently with Isabel’s strong interest in northern influenced artwork, we see other areas of Spain developing an interest in stylistic ideas from the Italian peninsula. While Isabel’s court had a strong interest in Italian humanism and philosophy, it had little interest in its visual aesthetics.

The introduction of Italianizing influences

In the final third of the fifteenth century, especially in Valencia, we begin to see Italian influences. Italian artists also began to arrive and work in Spain, among them Nicola Fiorentino, Francesco Pagano, and Paolo da San Leocadio. These Italianate influences are visible in artworks by Spanish artists like Bermejo. Valencia would become important as a crossroads of Spanish, Netherlandish, and Italian painting. Some have credited the interest in Italian art with the arrival of cardinal Rodrigo de Borja, bishop of Valencia and vice-chancellor of the church of Rome. He came to Valencia accompanied by Paolo da San Leocadio and Francesco Pagano.

The term “Hispano-Flemish”

Paintings like Gallego’s and Dalmau’s are often described as “Hispano-Flemish,” which is intended to highlight their indebtedness to Netherlandish painting though they were painted in Spain with Spanish influences as well. The term is ambiguous though, and for this reason, some people prefer the term “late Gothic” or even “final Gothic,” though these too are somewhat inaccurate. Still others will omit the use of stylistic terminology altogether and simply locate these paintings as being done in the Hispanic Kingdoms between the 1440s and early sixteenth century, and under the influence of Campin, van Eyck, and van der Weyden.

Additional resources:

Jonathan Brown, Painting in Spain 1500–1700 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998).

John F. Moffit, The Arts in Spain (London: Thames and Hudson, 1999).

Judith Berg Sobreé, The Artistic Splendor of the Spanish Kingdoms: The Art of Fifteenth-Century Spain (Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 1996).

Alberto Velasco and Francesc Fité, eds., Late Gothic Painting in the Crown of Aragon and Hispanic Kingdoms (Leiden: Brill, 2018).

St. Michael defeats the devil in Renaissance Spain

by DR. LAUREN KILROY-EWBANK and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Master of Belmonte, St Michael Defeating the Devil, 1450-1500, oil and tempera on wood (The Cloisters, The Metropolitan Museum of Art). Speakers: Dr. Lauren Kilroy Ewbank and Dr. Steven Zucker

The Renaissance in Spain, The Morata Master

by DR. LAUREN KILROY-EWBANK and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): The Morata Master, Virgin and Child Enthroned with Scenes from the Life of the Virgin, late fifteenth century, tempera and gold on wood, central panel, below 132.1 x 87.9 cm; central panel, above, 111.1 x 87.6 cm; each side panel 214.6 x 57.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art), this video is part of Smarthistory’s Expanded Renaissance Initiative Speakers: Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank and Dr. Beth Harris

Bartolomé Bermejo, Piedad with Canon Lluís Desplà

Piedad (in Italian: Pietà — the Virgin Mary cradling the dead body of Jesus)

Butterflies flutter beside a lion that sleeps peacefully. Flowers and other greenery spring from the reddish-brown earth, all painted with naturalistic precision. In the center foreground, the Virgin Mary mourns her dead son, holding him. Jesus’ broken body arcs across her lap, blood streaming from his wounds. On the left side, St. Jerome, dressed in red and white, kneels while paging through a book. At his feet we see a lion — a reference to the legend that St. Jerome tamed a lion in the wilderness by healing its paw.

To the right is the Canon Desplà, who lived in Barcelona, Spain during the fifteenth century, dressed in heavy black robes.

The landscape

While our attention is focused on the figures in the foreground who take up half of the composition, behind them is a vast and detailed landscape. It is filled with cities, windmills, mountains, rocky crags, pathways, waterfalls, rivers, and weather phenomena in the sky.

The artist, Bartolomé Bermejo, renders the landscape with exquisite details and a lush color palette, inviting viewers to delight in his naturalistic effects. It is clear that the artist has studied plants, animals, and insects, as he attempts to capture them faithfully. He uses the relatively new medium of oil paint to build up details and textures.

Bermejo’s careful observation of the natural world is paired with his imaginative depiction of Jerusalem in the background where the ancient city looks more like fifteenth-century Europe with its Gothic architecture (note the tall spires, delicate tracery, and rose windows) than an eastern Mediterranean city. Some buildings though, do have small domes, likely the artist’s attempt to reference Jerusalem’s famous domed spaces (such as the Dome of the Rock and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

Pairing convincing naturalism with creative invention made Bermejo one of the most original artists of his day. Piedad with Canon Lluís Desplà is Bermejo’s last known completed work before he mysteriously stopped producing art.

The auburn artist on the move

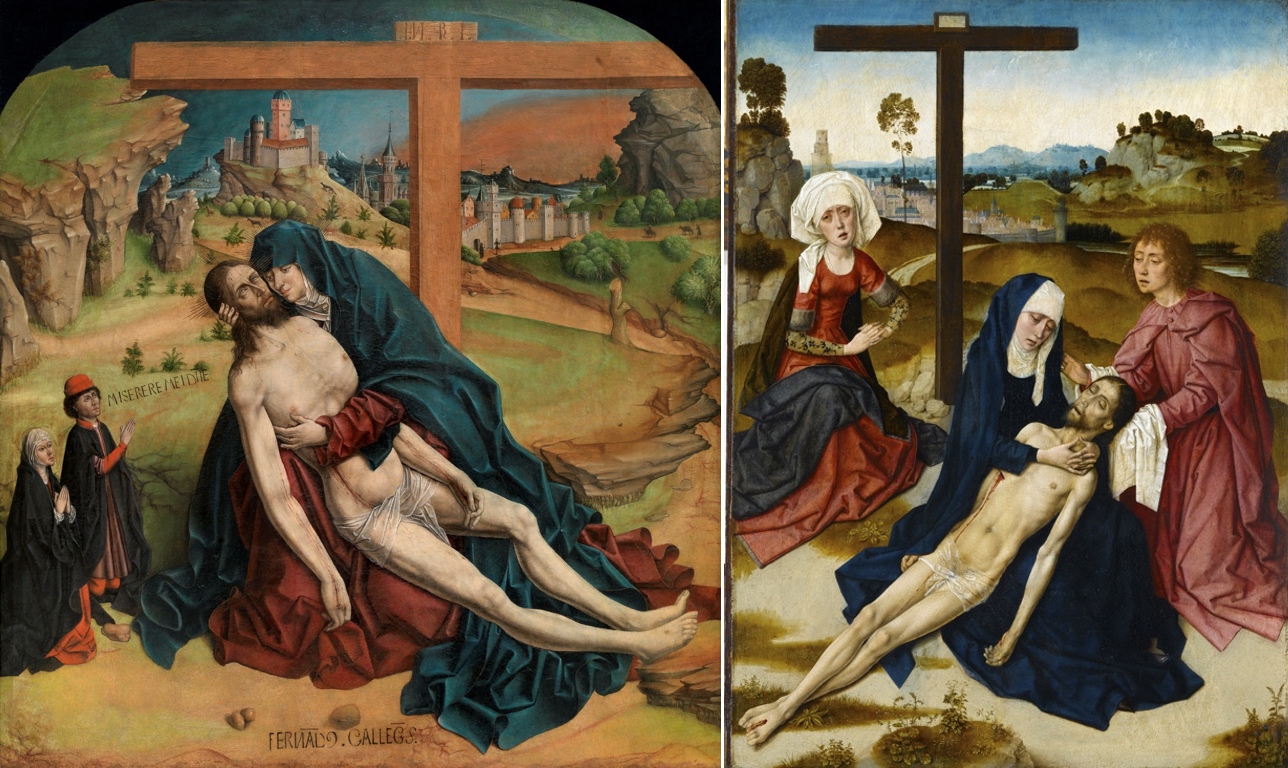

Bartolomé de Cárdenas, often called el Bermejo (which means “auburn” in Spanish), was likely born in the city of Córdoba on the Iberian peninsula around 1440. For much of his career he painted within the Kingdom of Aragón. We have artworks from cities like Valencia, Daroca, Zaragoza, and Barcelona, as well as some textual records that describe aspects of his time in these places. Unfortunately, many details of Bermejo’s life are currently unknown to us.

Bermejo is an example of an itinerant artist — someone who moved around a great deal during his lifetime. He never stayed anywhere for more than ten years. He had a reputation for not completing his work, and was even excommunicated at one point while in Daroca. It is likely that Bermejo was a converso, someone who converted from Judaism to Christianity. While in Daroca, Bermejo married a conversa named Gracia de Palaciano. At this time in Spain, many conversos were suspected of still practicing Judaism. At one point Gracia was called before the Inquisition for not knowing the Nicene Creed (a statement of belief widely used in Christian liturgy). Bermejo’s itinerancy might partially be explained by his being a converso.

Throughout his journeys, Bermejo absorbed and adapted different artistic strategies, including Flemish (Northern Renaissance) ones. It has been suggested that between the 1450s and 1460s, he may have apprenticed in Flanders, today primarily Belgium and the Netherlands, but we have no specific evidence that Bermejo ever traveled there as some other artists of his time did. It is more likely that he was coming into contact with Flemish art through Flemish artists who moved to the Iberian peninsula (Spain and Portugal), and Spanish artists who themselves had also absorbed Flemish artistic ideas. Valencia was well-known as an international and cosmopolitan city, complete with artists from northern Europe as well as merchants selling artworks acquired from there.

Naturalism and observation

Earlier fifteenth century depictions of the Piedad, such as Fernando Gallego’s painting of this subject, reveal a similar interest in panoramic landscapes, and are similarly influenced by Flemish painting.

Scenes of the Pietà or Lamentation by Dieric Bouts and Petrus Christus reveal that Spanish artists like Gallego and Bermejo adapted elements from these Netherlandish painters. However, few artists (Flemish or Spanish) display the same keen observational interest in botanical elements or fauna as Bermejo does.

If we take a close look at the Virgin Mary’s blue mantle for example, we can see Bermejo’s extraordinary technical skills. The edge of the mantle is decorated with complex golden patterns, and he reveals the green lining as a way to portray the different angles and textures of the textile.

The artist also shows more naturalistic folds in the mantle than the more stylized, angular drapery characteristic of Flemish and Spanish painting of the time (this is especially evident in Gallego’s Piedad). The oil glazing that Bermejo uses also permits him to pay close attention to details. There are more than forty types of plants in the painting, providing viewers with great botanical variety.

More than meets the eye

While Bermejo’s observational skills are on full display in this painting, many of the animals and plants also have deeper symbolic meaning. Small red and white blossoms dot the landscape, symbolizing purity (white) and passion (red). White and orange butterflies flutter around the composition, likely symbolizing resurrection. On the right side of the painting are several European goldfinches (symbols of the Passion and Resurrection). A snake slithers away between the rocks, and a mouse flees into the grass. Both are associated with Satan or evil, and the idea here is that evil is being driven away.

A pile of exposed bones rests behind Mary and her son. It is common to see a human skull and crossbones at the base of the cross in images of the Crucifixion, Lamentation, and Pietà. The bones are Adam’s, and it locates the Crucifixion at Golgotha (Calvary), the “place of the skull,” in Jerusalem. Bermejo also uses them to signal his skill, by depicting more bones than we might normally observe in a such a scene, but also including more difficult bones to paint, such as vertebrae.

Different types of weather phenomena take place across the sky, with Bermejo creating various atmospheric effects. On the left, we see thick cumulus clouds and rain pouring down. A blackened sky fills the top portion of the sky, partially obscuring the moon. Closer to the earth in the center of the landscape the clouds begin to clear, and birds fly in straight formation off to the right side of the sky. The rightmost section of the sky is red and golden, and the sun is likely further off to the right. The storms and dark threatening sky refers to the passage in the Gospels about the darkness following Jesus’ death and a possible eclipse. Where the sun should be in the composition, if it were paired with the moon, is the top most portion of the cross. Bermejo may be substituting the top of the cross for the sun to convey the idea that Jesus is the light of the world (the lux mundi), and his death and resurrection allow for entry into the heavenly Jerusalem.

Haloes

Jesus, Mary, and Jerome’s haloes look more like golden metal crowns or additions that we see on late medieval and renaissance Spanish sculpture. They differ from painted haloes that we tend to think of in the late fifteenth century in other areas of Europe, often golden disks surrounding the head. Earlier Spanish artists, like Gallego, similarly include the halo as rays of light.

Canon Desplà and Renaissance Humanism

The Piedad described here was completed in 1490 for a chapel belonging to Canon Lluís Desplà i d’Oms in Barcelona Cathedral. Canon Desplà was an archdeacon, and a learned classical humanist. He had Bermejo include his portrait in the painting likely to both advertise his position and demonstrate his piety and contrition as he kneels forever next to Mary and Jesus. The portrait displays great realism. It shows Desplà in three-quarter profile, bearded and with a contemporary haircut. He wears clothes of his time. Bermejo does not idealize his patron, instead painting the canon with sagging skin under his eyes, and other imperfections around the mouth.

While Bermejo’s depiction of St. Jerome is not a portrait, it has portrait-like qualities. Jerome pages through an open book, the written words legible to the viewer, seeming to read about the Piedad as it occurs before him. Bermejo likely included the scholarly Jerome, with his accompanying feline friend, because of the saint’s association with learning, which would have appealed to humanists such as Desplà.

Bermejo signed his painting on the frame with the words, “Opus.Bartolomei.Vermeio.Cordubensis” (Work of Bartolome Bermejo of Córdoba).[1] The all capital letter inscription is done in a classicizing manner, evoking antique Latin inscriptions. This may reveal Bermejo’s interest in ancient Roman culture, perhaps studying first-hand the Roman monuments found in Iberia. Because Bermejo’s patron was also a humanist antiquarian, the artist’s choice could have been Desplà’s.

Bermejo’s Piedad is an exceptional painting that embodies much of the artistic transformation and innovation taking place across different parts of Europe. His empirical approach to the representation of plants and animals was one shared by other artists of this time, like Leonardo da Vinci, and which he uses to create powerful symbolic messages about Christ’s sacrifice and the hope of salvation.

Notes:

[1] OPVS. BARTHOLOMEI. VERMEIO. CORDVBENSIS. IMPENSA. LODOVICI. DE. SPLA. BARCINONENSIS. ARCHIDIACONI. ABSOLUTUM. XXIII. APRILIS. ANNO. SALVTIS. CHRISTIANA (E). MCCCC. LXXXX

Additional resources:

Read more about Renaissance art in Spain

Read more about fifteenth-century Spanish painting

Prado’s short video on Bermejo, and a series of brief essays related to the exhibition (Spanish and English)

John F. Moffit, The Arts in Spain (London: Thames and Hudson, 1999)

Letizia Treves, et. al. Bartolomé Bermejo, exh. cat. (London and New Haven: National Gallery Company and Yale University Press, 2019)

Alberto Velasco and Francesc Fité, eds., Late Gothic Painting in the Crown of Aragon and Hispanic Kingdoms (Leiden: Brill, 2018)

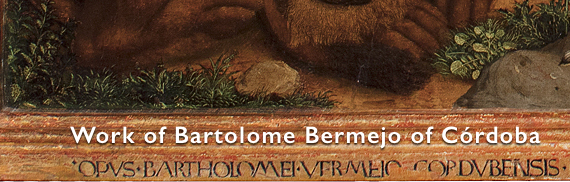

Gil de Siloé

A Renaissance St. James as pilgrim

by DR. LAUREN KILROY-EWBANK and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Gil de Siloé (Burgos, Castile-León, Spain), Saint James the Greater, c. 1489–93, alabaster with traces of paint and gilding, 45.9 x 17.4 x 12.5 cm (The Cloisters, The Metropolitan Museum of Art), an Expanded Renaissance Initiative video, speakers: Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank and Dr. Beth Harris

Additional resources

Gil de Siloé, The Tomb of Juan II of Castile and Isabel of Portugal

If you suddenly found yourself heir to a throne, one that your family members felt belonged to them, what steps would you take to advertise that you are indeed the rightful inheritor? In 1486, Queen Isabel of Castile found herself in just this position. And she needed to communicate to her subjects that she was the rightful heir to the royal throne. One way she did this was to commission the sculptor Gil de Siloé to create an elaborate star-shaped tomb in honor of her parents, to be placed before the main altar in the Carthusian Monastery of Miraflores (near Burgos) in Spain.

The impressive and ornate tomb is made entirely of alabaster, which was admired for its translucency and desired for the ease with which one could carve it. The elaborate tomb was not created solely as a commemorative monument though. Isabel also intended to make a political statement about her right to rule from the throne of Castile, which some of her family members wanted for themselves.

The elaborate tomb tells us a great deal about art and artists in fifteenth-century Spain, political power struggles, patronage concerns, and the importance of alabaster as a medium in the renaissance.

The tomb

The ambitious tomb was a massive monument that was arranged as an eight-pointed, star-shaped platform. On top of the platform rested two life-sized effigies of Juan II of Castile and Isabel of Portugal, the parents of Queen Isabel. Lions rest at their feet. These felines are commonly found on royal or noble tombs of this time. As strong animals, lions symbolized power and also served as protectors. Isabel holds a prayer book, a sign of her piety. Juan II raises his right hand, while his left hand pulls on his robe, allowing Gil de Siloé to flaunt his skill at creating naturalistic folds in clothing. Above them are elaborate canopies and to their side are slim colonnettes, both of which make the two figures appear as if they are on a church facade rather than reclining on a tomb.

Surrounding the royal couple are smaller figures of the four Evangelists, seated at the four cardinal directions. The twelve apostles of Jesus are also atop the platform. One of the original apostles was removed, and is now in the Cloisters Museum of Art in New York City, with a replica on the tomb itself. It is an important reminder that artworks are often modified over time, attesting to their ongoing lives after their moment of creation.

Below the royal effigies are Old Testament figures (no longer in their original arrangement), who literally support the figures above them. Lions also adorn the sides, protecting the Castilian coats of arms. Many of the figures here also rest between delicate colonettes, adding to the architectural quality of the tomb.

The monument is a visual feast for the eyes. The sculptor created a complex surface design with an abundance of details, all done with a delicacy that makes the tomb appear more like a work done in metal than in stone. Elaborate tracery (ornamental stone openwork) animates much of the tomb. The clothing of the life-sized figures has a rich surface design and naturalistic texture, as if Gil de Siloé wanted to capture the sense of silks and brocades in stone.

Other naturalistic details can be found throughout the monument, such as the faces and hair of the royal couple, and the way that fabrics hang on the bodies of the figures. Juan II’s skin shows signs of aging, with slightly sagging jowls, which adds to the portrait-like quality of the effigies. The interest in detailed surface texture and naturalistic details parallels what we find in Spanish and Flemish painting of the time.

Flemish art and artists (in Northern Europe), among them Gil de Siloé, found a home on the Iberian peninsula in the fifteenth century, adding to the complex visual culture we find there. The tomb’s appearance has also been compared to Mudéjar art (Christian art heavily influenced by Islamic art), specifically for its heavy patterning and rhythmic repetition of complex forms.

Stylistically, scholars have labeled this tomb as late Gothic or as Isabelline, although it falls within the era of the early renaissance in northern Europe and Italy—places where we still find the influence of Gothic art as well. The term Isabelline is one more frequently attached to architecture created during the reign of Isabel and Ferdinand of Aragon, her husband. The so-called Isabelline style is one that borrows from Islamic or Mudéjar traditions, northern European styles, some classicizing forms, and even complex silverwork designs. The many ways that we might label the tomb’s style speaks to some of the challenges that art historians face when naming things, especially when these terms were created to describe art in other places.

The material

Often when we think of sculpture from the fifteenth or sixteenth centuries, we think of marble and bronze sculptures, or perhaps wooden ones. Alabaster was also a common medium in which many sculptors created dazzling objects, such as the tomb of Juan II and Isabel of Portugal. Alabaster became popular as a material for altars and tombs beginning in the late Middle Ages in Spain, the Burgundian Netherlands, and England. It was frequently painted and gilded, and there are traces of paint and gold on Siloé’s sculpture. Unpainted, alabaster can range in color from white to pink to yellow, and can have streaks in it as well, as we can clearly see in the figure of St. Luke on the tomb.

Alabaster sculpture has been ignored in art historical scholarship, with preference given to marble sculpture in the renaissance. Marble was the favored stone in Italy, but not as much in other places. Alabaster appealed to people because of the ease with which one could cut and polish it, its greater luster and translucency, and its ability to take paint well with a generous coating of gesso (a mix of an animal glue binder, chalk, and white pigment), although it did not fare well outdoors. It was soft enough that sculptors could use woodworking tools to carve it. Spain has abundant alabaster reserves, which is a main reason for the stone’s popularity in the medieval and renaissance eras. In the fifteenth century, there was no sense that alabaster was inferior to marble.

The artist

Gil de Siloé originally came from northern Europe, most likely the Netherlands. Like some other artists of the fifteenth century, he traveled to Castile, presumably to find work. While in Spain, he was one of the best sculptors of his day. While he sculpted in various media, his alabaster works are among the finest. His skill with the tools of his trade did not go unnoticed; he had a number of important patrons, including Isabel.

The patron and the commission

For this tomb, Gil de Siloé found himself a royal patron in the figure of Queen Isabel of Castile. Isabel had a fondness for northern art, likely due to her father’s interest in it as well. Her official court painter in the late fifteenth century was Juan de Flandes, or John of Flanders, and she had a number of other northern artists work for her during her life, including Gil de Siloé.

After Isabel commissioned her parents’ tomb from Gil de Siloé, he sculpted it between 1489 and 1493. Isabel had good reason to want to showcase her parents in such an elaborate tomb. It commemorates Juan and his second wife (Isabel’s mother), which was important because Isabel’s accession to the throne depended on her legitimate royal lineage. The tomb functions like a large advertisement noting her dynastic claims to the throne for anyone who called them into doubt. Juan II of Castile had also donated his hunting lodge to the Carthusians in 1442, at which point it was transformed into a monastery. Having Gil de Siloé place a tomb in this location reminded people of Juan II’s donation, which Isabel felt would aid her in further legitimizing her rule.

This singular monument reveals so much to us about late fifteenth-century Spanish art and the important role that it could play in political maneuverings. It also helps us to think beyond the borders of what we traditionally think of as “renaissance sculpture.”

Additional resources:

Gil de Siloé’s sculpture of St. James the Greater at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Read more about fifteenth-century Spanish painting on Smarthistory

John F. Moffit, The Arts in Spain (London: Thames and Hudson, 1999).

Judith Berg Sobreé, The Artistic Splendor of the Spanish Kingdoms: The Art of Fifteenth-Century Spain (Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 1996).

Alberto Velasco and Francesc Fité, eds., Late Gothic Painting in the Crown of Aragon and Hispanic Kingdoms (Leiden: Brill, 2018).

16th century

Juan de Flandes

A miraculous appearance for a queen: Juan de Flandes, Christ Appearing to His Mother

by DR. LAUREN KILROY-EWBANK and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Juan de Flandes, Christ Appearing to His Mother, c. 1496, oil on wood, 62.2 x 37.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Test yourself with a quiz!

START

Additional resources

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

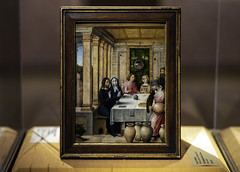

A wedding and a miracle for the queen of Spain

by DR. LAUREN KILROY-EWBANK and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): Juan de Flandes, Marriage at Cana, c. 1500–04, oil on wood panel, 21 x 15.9 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Additional Resources

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Alonso Berruguete

Bringing the figure to life

by DR. LAUREN KILROY-EWBANK and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

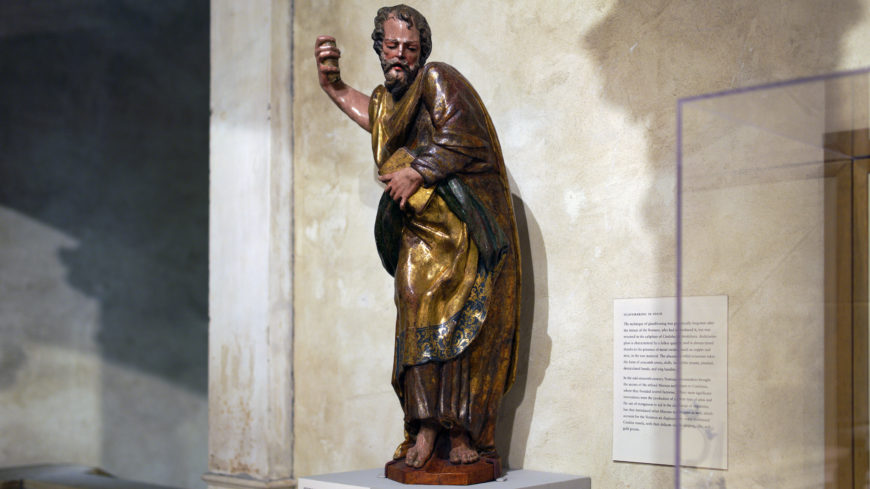

Video \(\PageIndex{6}\): Alonso Berruguete, Apostle or Saint, c. 1520s, polychrome and gilded walnut, 103 x 37 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art), part of Smarthistory’s Expanded Renaissance Initiative

Introduction

Alonso Berruguete was one of the most important artists of renaissance Spain, excelling at painting and sculpture among other things. Today he is well-known for his sculptures, which testify to his remarkable ability to carve marble, alabaster, or wood. This sculpture is polychromed (painted) wood.

As a young artist he traveled to Italy in 1504, where he came into contact with Michelangelo and engaged with his art while in Rome. He spent most of his time in Florence, painting in the mannerist style (Mannerism is a late renaissance style). After his return to Spain in 1518, he was made the king’s court artist, but primarily turned to sculpture for the remainder of his life. He and his workshop made elaborate retablos (altarpieces), which often took up the entirety of the apse of a church and required carpenters, gilders, painters, and sculptors to create such towering and impressive religious artworks.

While we do not know exactly who is depicted in this sculpture of the saint at The Metropolitan Museum of art, it offers a powerful example of Berruguete’s mannerist tendencies, his skill at carving in wood, and his work on religious retablos. It is most likely a sculpture that once rested on the corner of a retablo, indicated by the uncarved and unpainted back.

Berruguete’s life as an artist also reminds us of the mobility of artists in the sixteenth century. They moved around — to train, to study, and to find work. Today we tend to associate artists with a specific region or modern-day nation, but in the sixteenth century (and earlier) artists were often on the move.

Terms and key ideas

- Renaissance Spanish art

- Polychromed wooden sculpture

- Artists on the move

- Mannerist sculpture

Test yourself with a quiz!

START

Additional resources:

Learn more about making a Spanish polychrome sculpture

Read more about the medieval and renaissance altarpiece

Read more about mannerism

See one of Berruguete’s paintings at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence

Watch a video made by the National Gallery of Art about Berruguete

Read about the process of creating one of Berruguete’s retablos

C. D. Dickerson III, Mark P. McDonald, eds., Alonso Berruguete: First Sculptor of Renaissance Spain, exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019)

For the classroom

Take notes while watching the video, using the Berruguete Active Video Note-Taking

Discussion questions \(\PageIndex{1}\)

- Compare Berruguete’s sculpture with Juan Martínez Montañés and Francisco Pacheco’s Christ of Clemency. What does this comparison tell us about polychromed wood sculpture in Spain?

- Compare Berruguete’s sculpture with Giambologna’s Abduction of a Sabine Woman. How are they both mannerist? In what ways do they differ?

- Consider the role of Berruguete’s sculpture as a cultural artifact. Without being able to identify the specific identification of the sculpted figure, what other methods can we use to understand the sculpture’s role in renaissance Spain? Is something lost by not being able to identify the specific individual?

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

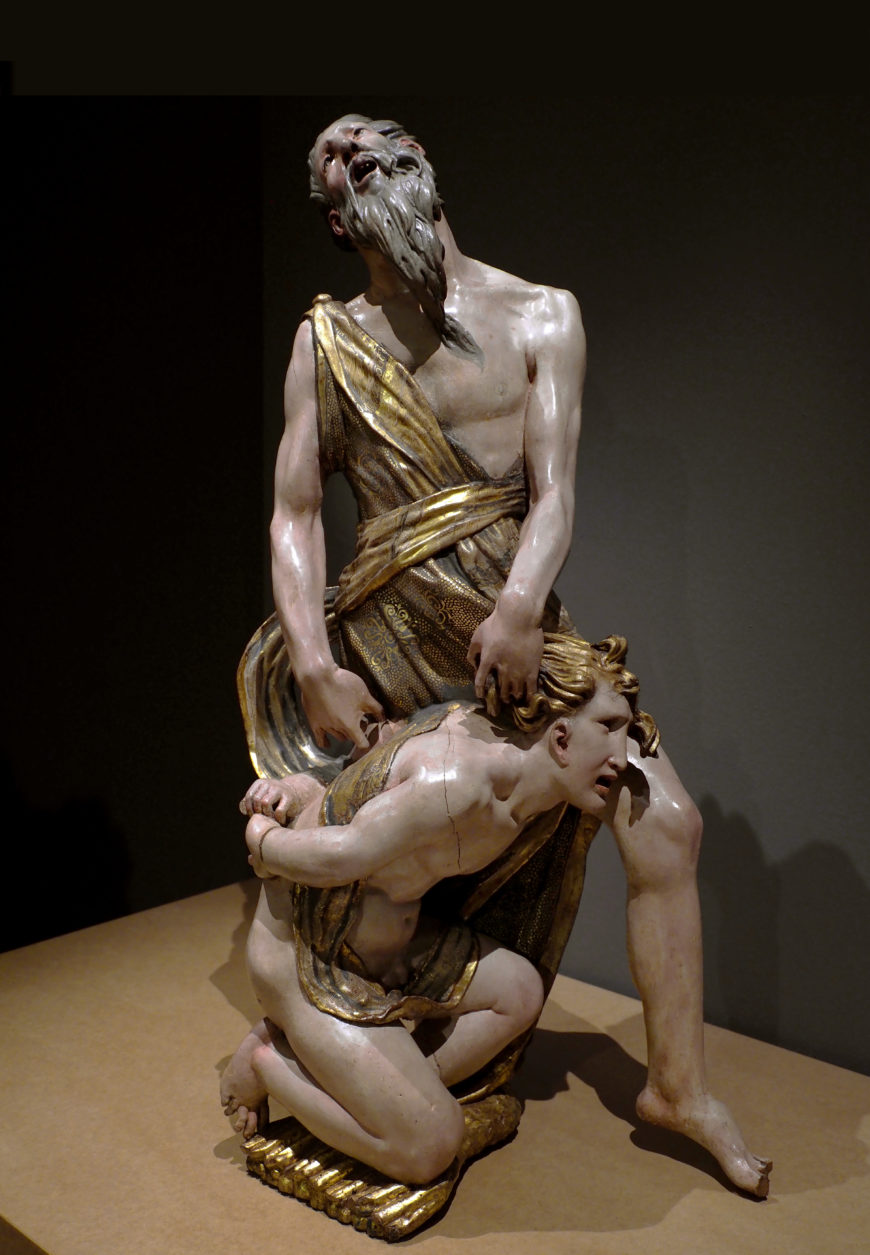

Alonso Berruguete, Abraham and Isaac

Alonso Berruguete is possibly the most famous sculptor that you have never heard of. He began his life in Paredes de Nava, a small town in northern Castile, which was by no means a major artistic center. From these remote beginnings, Berruguete rose to extraordinary success, courting some of the wealthiest and most powerful patrons on the Iberian Peninsula (what is today Spain and Portugal). After his death, Berruguete was eulogized by his peers as among the greatest artists of his time, and sculptures like his Abraham and Isaac were among the works of art for which he was most enthusiastically celebrated. Indeed, Abraham and Isaac was part of the larger-scale sculptural work that cemented Berruguete’s reputation as one of the most exciting sculptors in renaissance Spain.

The Retablo of San Benito el Real

Abraham and Isaac is one small piece of a commission that Berruguete received in 1526 from the Monastery of San Benito el Real in Valladolid, the cultural capital of the region of Castile and León. The commission was for a retablo (a large and elaborate wooden altarpiece) of the kind that was installed in churches all over Spain. Berruguete was at a crucial turning point in his career, having already finished his artistic training and gone to work, however briefly, for King Charles I of Spain (later Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor). By then, Berruguete commanded an impressive workshop of assistants and was ready to take on his most ambitious project yet.

Like other retablos of the period, the Retablo of San Benito el Real is a visually dazzling combination of sculpted, painted, and architectural elements (although it was at one point split apart and no longer exists in its finished state). Scenes from the Christian Bible—some fully painted, others carved in relief and then polychromed—appear framed by richly ornamented columns and pedestals. The life-sized figure of Saint Benedict (San Benito in Spanish) towers at the center of the composition, his hand lifted in blessing. At the top of the retablo is an enormous gilded shell with the Crucifixion rising above it. At the bottom is a series of architectural niches (many of which do not survive), each of which contained biblical figures sculpted in the round. Abraham and Isaac originally stood in one of these niches.

The subject and iconography

The subject of Abraham and Isaac derives from a story in the Old Testament. In the Book of Genesis, God tells Abraham, a shepherd and the first of the patriarchs of Judaism, to offer his only son, Isaac, as a sacrifice to Him. Following God’s instructions, Abraham takes Isaac to a mountaintop, where he prepares an altar with firewood. He binds his son and lays him on the altar, lifting a knife to kill him. Before Abraham can do so however, an angel appears from Heaven and stops him, replacing Isaac with a lamb for the sacrifice. In Abraham’s willingness to take His commands over and against his love for his only child, God sees an expression of Abraham’s faith and rewards that faith with the promise of more sons to come.

Depictions of this scene in renaissance art are overwhelmingly focused on the dramatic actions that drive this story forward: Abraham’s swinging of the knife into the air, or God’s angel tumbling down from the sky in a moment of literal divine intervention. This is the approach taken by contemporaries like Titian, Paolo Veronese, and Andrea del Sarto.

Berruguete’s approach suggests a different set of priorities, heightening instead the intensity of emotions expressed by Abraham and Isaac. The sculpture represents a moment of despair, the faces of both father and son distorted into screams. They do not yet know that salvation is coming. They only know the deed that is to be done—and the tremendous cost of it.

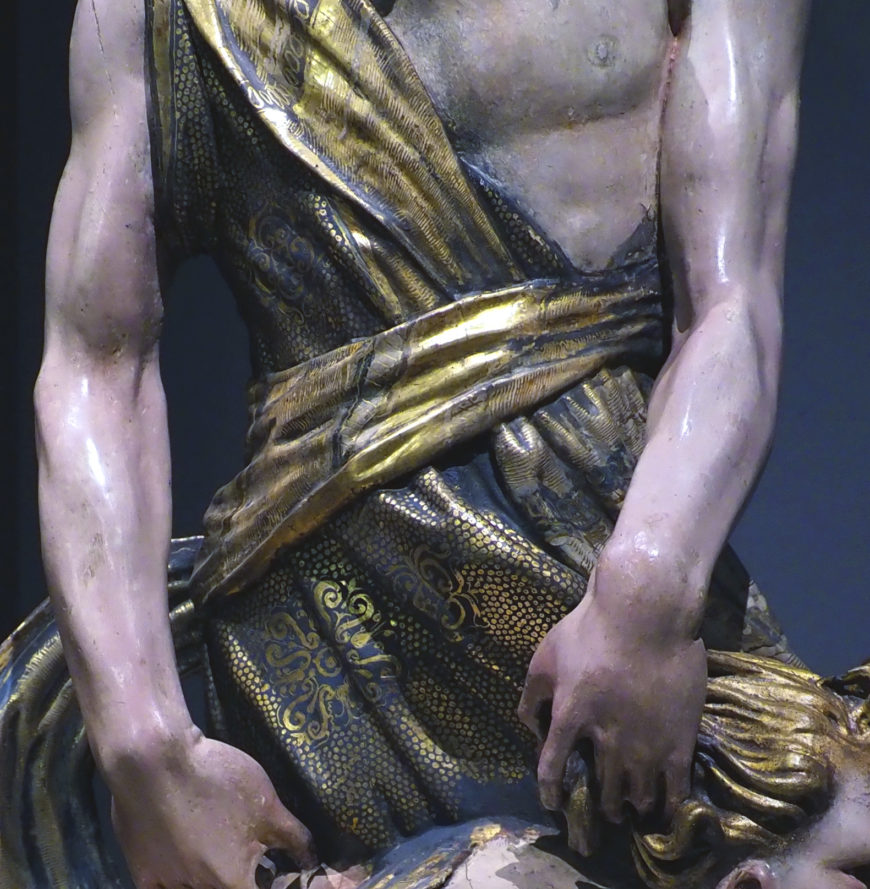

Techniques in polychrome

The affective power of Berruguete’s wooden sculpture is thanks in part to its brilliant polychrome. The draperies that wrap around the body of Abraham and swirl across Isaac’s torso were made using the Spanish estofado technique. Berruguete and his assistants would have begun by covering the finished wooden figures first in gesso (glue mixed with plaster), then in bole (largely made of clay). After dampening the surface with water, gold-leaf was carefully applied, let dry, and polished. Finally, a layer of tempera was painted over the gilding. Once dry, the paint was scratched away to reveal the gold layer underneath, resulting in glittering geometric and floral designs.

But the sculpture gets its lifelikeness especially from the technique used to paint the faces and bodies of Abraham and Isaac, called encarnación. These parts of the sculpture, once covered in gesso, were then coated in lead white paint. From there, the details of skin tone and hair were carefully painted in, with pink glazes used to give the sculpture the warmth and vitality of human life. Each stage of the production of a polychrome sculpture—from carving to estofado and encarnación—would have required a particular skill set. Berruguete’s workshop employed carpenters, gilders, painters, woodcarvers, and other specialists who worked together under his guidance to realize his grand designs.

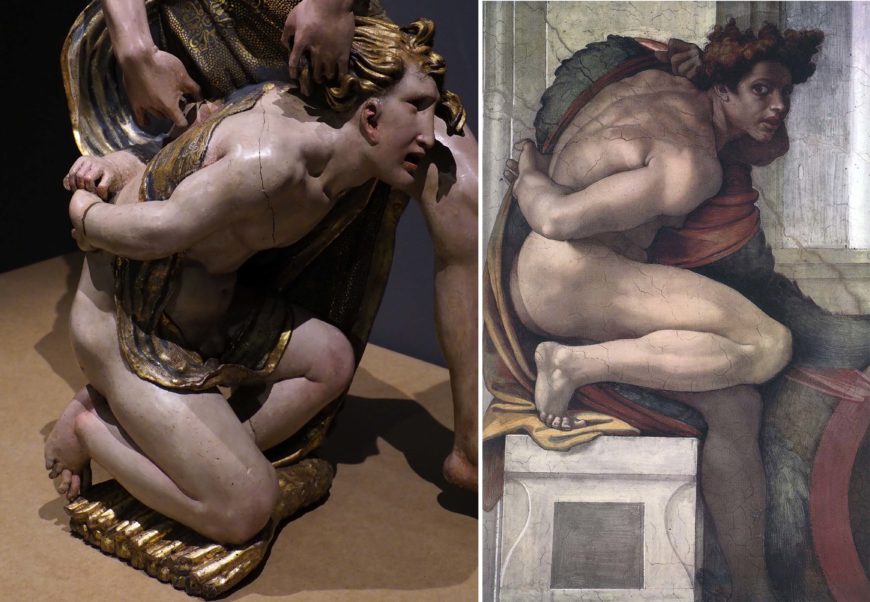

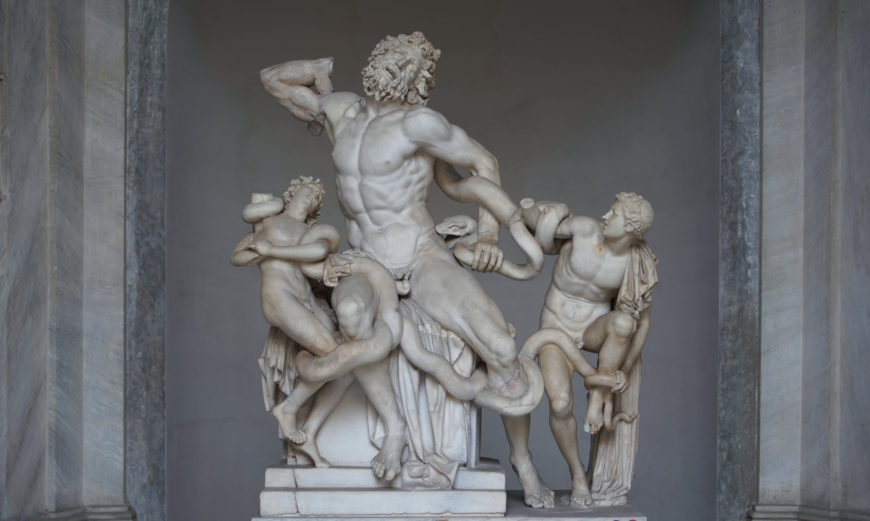

Michelangelo’s Laocoön

Abraham and Isaac also owes much to Berruguete’s training in Italy. Sometime between around 1506 and 1518, Berruguete travelled between Florence, Rome, and other major centers to study art. While there, he came into the orbit of Michelangelo, who at the time was occupied with the painting of the Sistine Chapel ceiling. It was a transformative phase for Berruguete. In these years, he made several drawings and paintings that reflect his careful study of Michelangelo’s work. This study paid off when Berruguete returned to Spain and got to work on sculptural commissions like the Retablo of San Benito el Real. Several of the figures on the retablo owe their poses to the sibyls and prophets on Michelangelo’s ceiling, including those depicted in Abraham and Isaac. With his torso bent over and his arms twisted behind his back, Berruguete’s Isaac is a close copy of one of the many nudes in Michelangelo’s famous fresco.

Berruguete’s travels in Italy also coincided with an important moment in the history of renaissance art. In 1506, an ancient marble was excavated in Rome: Laocoön, a Hellenistic work depicting a scene from Virgil’s Aeneid. In this scene, a Trojan priest and his two sons are consumed by giant snakes that emerged from the sea. As a striking portrayal of human agony, the sculpture was a sensation. None other than Michelangelo was tasked with its restoration.

There can be no doubt that Berruguete saw this sculpture and appreciated what it could teach him about the expressive power of art. In its basic composition, Berruguete’s Abraham and Isaac perhaps more closely resembles a sculpture like Donatello’s take on the same subject, made for the Florentine Duomo in 1421, but its extreme pathos was drawn from Laöcoon, a work whose influence can be felt all over the twisting bodies and contorted faces that came to characterize Berruguete’s sculpted output, such as the saint or apostle now in The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Berruguete’s Tomb of Cardinal Juan Pardo de Tavera and El Greco’s Laocoön

Berruguete’s ability to convey intense emotion in his sculptures remained one of the hallmarks of his oeuvre through the end of his life. His last great work was a marble tomb of the Cardinal Juan Pardo de Tavera, the archbishop of Toledo, for the Hospital de San Juan Bautista. Even here Berruguete demonstrates his ability to capture the depth of human feeling. The tomb depicts the cardinal at the moment of his death. His eyelids fall heavily over his eyes, and his cheeks appear sunken and hollow. Nestled against this fading face is another one—a shrieking figure on the crozier tucked against the cardinal’s cheek. Here, we see the echoes of Abraham and Isaac’s screaming visages.

Tavera’s marble tomb remains in Toledo, where Berruguete spent the final decades of his life and career. He cannot have known that less than twenty years later Toledo would nurture another luminary of Spanish art: Doménikos Theotokópoulos (an artist who was originally from Crete), now best known as “El Greco.” Berruguete’s brilliance was not lost on the rising painter. In marginal notes that he made in his copy of Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, El Greco praised Berruguete’s accomplishments in painting, sculpture, and architecture. Almost exactly a century after Berruguete saw Laocoön in Italy, El Greco made a painting of the very same subject. It is hard to imagine that he did so without the legacy of the Spanish renaissance master in mind.

Notes:

- D. Dickerson III and Mark McDonald, eds., Alonso Berruguete: First Sculptor of Renaissance Spain (Washington: National Gallery of Art; Dallas: Meadows Museum, SMU; Madrid and New York: Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica/Center for Spain in America; New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2019)

Additional resources

Watch a short video about Berruguete from the National Gallery of Art’s exhibition, Alonso Berruguete: First Sculptor of Renaissance Spain

Read “Berruguete in Process: The Retablo of San Benito” from the National Gallery of Art

Learn more about how to make a Spanish polychrome sculpture from the J. Paul Getty Museum

Watch a short video in ASL about El Greco’s Laocoön from the National Gallery of Art

Manuel Arias Martínez, ed., Son of the Laocoön. Alonso Berruguete and Pagan Antiquity (Madrid: Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica, 2018)

Lynn Catterson, “Michelangelo’s ‘Laocoön?’,” Artibus et Historiae 26, no. 52 (2005), pp. 29–56

Sepulchre of Cardenal Tavera by Factum Foundation

Alejo Fernández, The Virgin of the Navigators

Floating on a cloud above a harbor, the Virgin Mary’s graceful figure stretches upwards. Her resplendent brocade dress, blond curls, and the golden rays encircling her head transform her into a beacon of light. The pink rays of dawn cut through the clouds at the top, suggesting Mary is like the sun rising to light another day. Though she towers over the diminutive figures kneeling around her, she opens her arms in a welcoming gesture.

Mary tips her head downward, looking demurely toward her mortal companions and the sea below. As if the breeze from the sea could reach the clouds, her blue pallium (or cloak) billows outward, enveloping the faithful kneeling below her as though to offer comfort and protection. The artist, Spanish painter Alejo Fernández, shows Mary in hieratic scale (larger than the worshippers below) to denote her importance as the holy mother of Jesus and as a co-redeemer (or co-redemtrix) in the salvation of humankind.

Fernández made only the central panel with the Virgin Mary; other artists made the smaller flanking panels showing saints.

If we read The Virgin of the Navigators (or The Virgin of the Seafarers) closely, we can learn an enormous amount about Spain’s role in late fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century exploration, trade and commerce, conquest and colonization, and slavery.

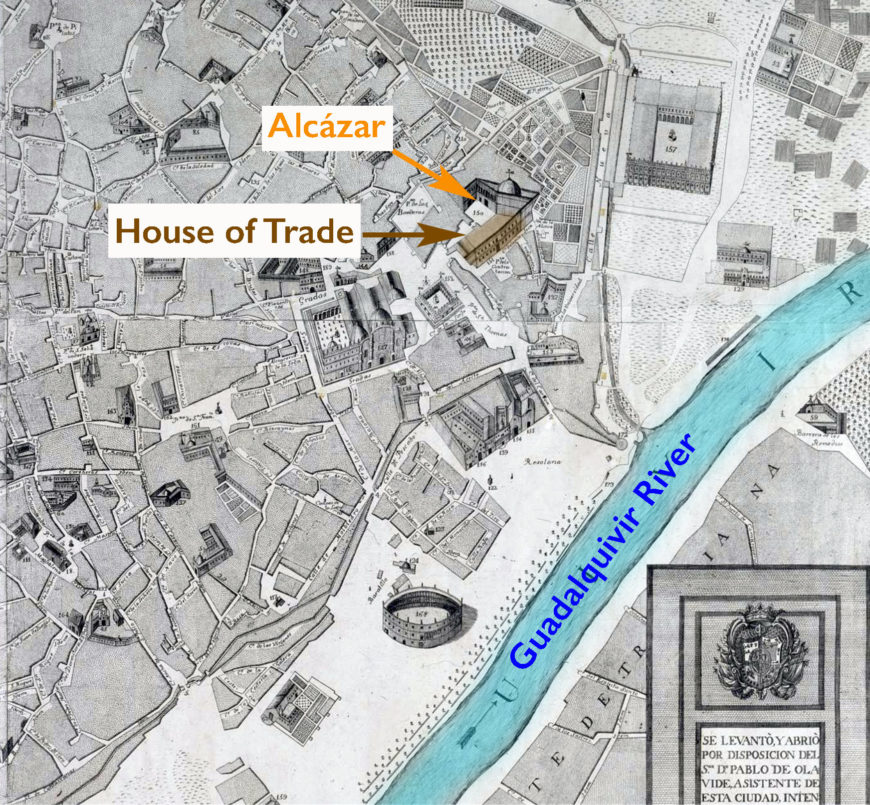

Seville as a port city and the House of Trade

To understand the painting’s complex subject matter, it is important to know who commissioned it (the patrons) and where it was originally located.

The Virgin of the Navigators is the central panel of an altarpiece designed for a chapel in Seville’s House of Trade (in the Alcázar, a royal palace). The House of Trade (Casa de Contratación in Spanish) was established in 1503 by the Spanish Catholic monarchs, Isabel and Ferdinand, and played an important role in commercial activities between Spain and the Americas. Anything imported from—or exported to—Spain’s new American colonies passed through the House of Trade. Ships sailing to the Americas left from and returned to Seville (by way of the Guadalquivir, a navigable river), making the city an important hub of mercantile activity and international trade.

Members of the House of Trade commissioned the painting from Fernández, a renowned artist of the time who was highly regarded for his portraits and religious canvases. Fernández’s painting highlights the roles that Spanish rulers and the Catholic Church played in acquiring new territories, resources, and people, as well as their role in conquest, colonization, and commerce. The Virgin blesses these exploits, acting as a protectress to individuals associated with the House of Trade. Her luxurious dress—a brocade made of silk fabric and gold thread—also points to the Casa’s commercial activities. Brocades were costly import items, most likely imported from Italy (possibly Florence) or even further abroad. Clothing Mary in a costly dress emphasizes her importance and connects her to the commercial activities of the painting’s patrons.

The Virgin of Mercy in 1492

We see Mary with her arms open wide and her mantle wrapped around devotees. She is the Virgin of Mercy (in Spanish, Virgen de la Merced; in Italian, Madonna della Misericordia)—a subject that originated in the thirteenth century. Appearing this way, Mary is a symbol of protection, and images often include portraits of specific individuals or groups sheltered within her mantle (so wonderfully captured by the German name for this subject, Schutzmantelmadonna—“sheltering-cloak Madonna”). To have oneself portrayed alongside the merciful Mary was an effective way to demonstrate one’s piety and importance while garnering hope for her protection.

Some Marian subjects, including the Virgin of Mercy, increasingly communicated the idea that the holy mother (Mary) defends Christians from enemies. Mary had already developed these associations on the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal today) as Christian rulers tried to take territory from Muslim rulers (who had controlled regions of the Peninsula beginning in 711 C.E.). In 1492, Isabel and Ferdinand defeated the last Muslim stronghold on the Peninsula, in Granada. Muslims who were unwilling to convert were expelled, as were Jews. Campaigns against Muslims (in the Maghreb in North Africa and Ottoman Turks who ruled from Constantinople) continued into the sixteenth century. Stories of Mary’s divine intervention on behalf of Christians on and off the battlefield flourished.

1492 was also the year that Christopher Columbus, the Genovese explorer funded by Isabel and Ferdinand, journeyed across the Atlantic in search of a route to India. He would eventually land in the Caribbean, and his voyages would initiate the invasion and colonization of the Americas. The European discovery that millions of non-Christian Amerindian peoples lived in lands previously unknown to them also increased the fervent Christian belief that Christ’s Second Coming and the end of days was imminent.

Adding to the urgent need to prepare for the end of days were the religious transformations that resulted from the Protestant Reformation. According to tradition, in 1517, Augustinian monk Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses to a church door in Wittenberg, demanding the reform of the Catholic Church. His action sparked a violent rift between Catholics and those who became Protestants, and theological and military battles ensued. Adding further chaos to this moment, King Henry VIII broke from the Catholic Church to form the Church of England after the pope refused to grant him a marriage annulment from his first wife (a Spanish Catholic). With these events in mind, Fernández’s Virgin of Mercy had special appeal as a protectress at a time when the Catholic faith was under threat.

Men (and women) of empire

In the painting, Mary offers solace and protection to those individuals directly involved in colonization and evangelization of the Americas. Many of them would have been in Seville, where Fernández worked, and it is possible that, as a well-known portraitist, he was able to paint some of their likenesses based on his observations of them in the city.

Let’s look first at the three men kneeling on the cloud in the foreground on the right side. The man at the right, who wears light leggings and a brilliant red cape, and is thought to be Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés whose actions led to the overthrow of the Mexica Empire in Central Mexico. The man at the left of this group, who wears a beige military-style outfit, is not firmly identified, but is almost certainly another conquistador. The man at the center, and slightly behind, with red hair and a longer beard, is likely King Charles I of Spain (who became the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V). These three men were directly involved in the conquest and colonization of the Americas (Charles was also actively fighting Protestants in northern Europe).

If we turn to the group in the foreground on Mary’s other side (our left), we see seven men and two women (these women remain unidentified, but likely represent members of the Spanish court).[1] The man with a cane is often identified as Amerigo Vespucci, the Florentine explorer who also gave his name to the Americas.[2]

The young man in red is likely Martín Alonso Pinzón, who along with his brother had accompanied Columbus on his first voyage and continued to participate in Spain’s imperial exploratory enterprises. The white-haired man on the left with the luxurious fur-trimmed gold colored robe has been identified as Columbus.

For a man known to have dressed very simply, Columbus’s expensive clothes seem out of character. Some scholars have suggested this finery explicitly connected him to the magus-king (one of the Magi—the kings who traveled from afar to offer gifts to the newborn Christ). In many images of the Adoration of the Magi, the magus-king wears similarly expensive clothing. The Magi also symbolized the extension of Christianity to all peoples because they journeyed from a far corner of the world. By the 1530s, this expansion of Christianity into new lands was actively occurring. Columbus himself was a Cristo ferens, or Christ bearer, bringing the gospel across the Atlantic (in fact his Spanish name—Cristóbal—echoes the Cristo in Cristo ferens).

Justifying conquest and evangelization

Behind the men and women associated with carrying out Spain’s imperial mission are smaller figures, who fade into the recesses of Mary’s cloak. Fernández painted them with darker skin, and did not differentiate their appearance—despite his being a celebrated portraitist. We can just make out that men kneel on the left, women on the right. They all wear simple white cloaks draped across their torsos. With the Spanish colonial mission in full swing by the 1530s, these figures undoubtedly represent the huge number of Amerindian peoples actively being converted to Christianity. Fernández has homogenized the diverse groups of Indigenous peoples, choosing not to differentiate them; the group symbolizes all Native peoples. The impression is that they have been brought under the protective mantle of Christianity (figuratively and literally), justifying the violence of conquest and colonization.

The Native people’s clothing also relates to Spain’s evangelization efforts. The simple white cloths are similar to those worn during baptism, the Christian purification rite that initiates someone into the faith. From a Christian perspective, millions of Native peoples in the Americas needed to be converted to prepare and save their souls before Christ’s Second Coming.

Navigating the empire

In the bottom third of the painting, we leave the divine realm and wade into the earthly realm. A windy harbor is filled with the ships that made overseas exploration and expansion possible. Fernández has painted exquisite details that allow us to identify the types of ships. In the center is a nao (or carrack), with a wide, deep hull that could carry lots of people and cargo. Its size and maneuverability made it an ideal vessel for exploration and navigating wide-ranging trade routes. In the 1530s, you would have observed them leaving Seville as they embarked on journeys along the African coast to Asia or across the Atlantic. Columbus’s ship, the Santa María, was a nao, as were the ships of other famous European explorers such as Vasco da Gama and Ferdinand Magellan.

Also in the harbor are caravels, a galley, and other boats. Caravels were smaller and swifter than nao. Galleys, or the many oared ships that had a long history in the Mediterranean, were used as battleships and trade vessels in the Mediterranean and around the coast of Europe and Africa. All these ships would have been frequently observed in the Seville harbor because of the city’s key role in maritime trade, exploration, and colonial expansion. The Virgin of the Navigators makes good on her name: she protects those whose lifeblood is the sea.

Seville and the history of slavery

As Fernández began painting The Virgin of the Navigators, conquistador Francisco Pizarro and his men were making advances on the Inka Empire in South America, which was fragile at that moment because rival brothers desired the throne. News from the Americas—such as Pizarro’s eventual defeat of the Inka ruler Atahualpa—passed through Seville, with much of it filtered directly through the House of Trade.

Seville and the House of Trade also played an important role in the history of slavery. As the Portuguese explored the west African coast in the 15th century, they started to enslave people and bring them back to Iberia. By 1462, Portuguese slave traders had established themselves in Seville, and the city became a central location in the selling and distribution of enslaved Africans, and had a sizable enslaved population itself. The House of Trade was directly involved in the slave trade, managing the ships and money generated from it. Fernández himself had at least several enslaved Black and Native individuals who were involved in his workshop.

The transatlantic slave trade began shortly before Fernández created The Virgin of the Navigators. In the Spanish and Portuguese Americas, in areas of extensive or total depopulation of Indigenous people (their numbers were greatly reduced by diseases introduced by Europeans from which they were not immune, and by cruel labor practices) enslaved Africans were brought in and forced to harvest precious resources, develop the land, and build. In 1526, the first Portuguese ship brought enslaved Africans to Brazil, initiating four centuries of slavery in the Americas. The Portuguese were quickly joined by the Spanish, French, British, and Dutch (among others) who participated in the horrifying brutality of the transatlantic slave trade.

Connecting seas

Ocean travel is what connects these far-off places and peoples together. The ability to navigate the ocean made Columbus’s fateful voyage possible, and led to the construction of ships that would carry enslaved peoples to the Americas. Navigation of the seas allowed certain European kingdoms, polities, and regions to amass impressive wealth, to develop trade relationships across vast distances, and to come into contact with cultures very different from their own (often with devastating consequences). Accurate cartography and navigation had become essential, and great advances were made by the 1530s. The House of Trade—members of which had commissioned Fernández’s painting—also established a school devoted to the vital skills needed by those individuals called to sea. It is perhaps fitting then that Fernández would transform his Madonna into a Virgin of the Navigators, offering those individuals who worked in the House of Trade a holy protectress, someone to champion their livelihood, along with Spain’s imperial ambitions and colonial desires.

Notes:

[1] It is possible that one of the women is Isabel of Portugal, Charles’s wife.

[2] This figure has also been identified as Doctor Sancho de Matienzo, the initial head of the House of Trade (who had died by 1521).

Additional resources

The Portuguese in Africa on the Metropolitan’s Heilbrunn Timeline

Visual Culture of the Atlantic World on the Metropolitan’s Heilbrunn Timeline

Herman L. Bennett, African Kings and Black Slaves: Sovereignty and Dispossession in the Early Modern Atlantic (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019).

Jonathan Brown, Painting in Spain 1500–1700 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998).

Linda B. Hall, Teresa Eckmann, Mary, Mother and Warrior: The Virgin in Spain and the Americas (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004).

John F. Moffit, The Arts in Spain (London: Thames and Hudson, 1999).

Carla Rahn Phillips, “Visualizing Imperium: The Virgin of the Seafarers and Spain’s Self-Image in the Early Sixteenth Century,” Renaissance Quarterly 58 (2005), pp. 815–856.

Amy G. Remensnyder, La Conquistadora: The Virgin Mary at War and Peace in the Old and New Worlds (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

Enriqueta Vila Vilar, Adolfo Luis González Rodríguez, Antonio Acosta Rodríguez, La Casa de la Contratación y la navegación entre España y las Indias (Seville: Universidad de Sevilla, 2003).

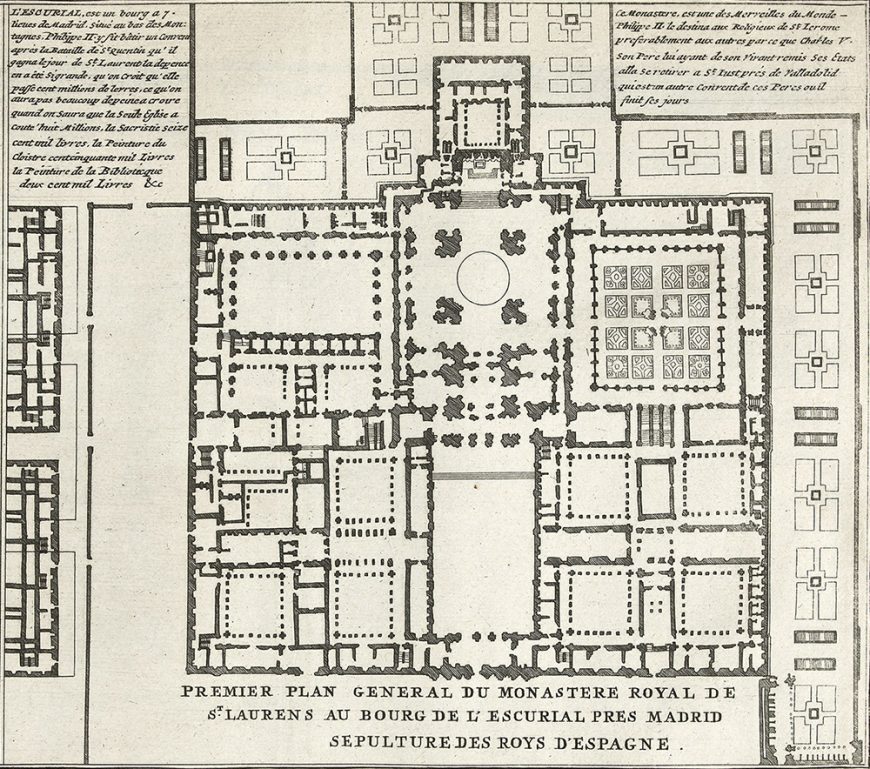

El Escorial, Spain

Located near Madrid, San Lorenzo de El Escorial is an imposing architectural complex that is arguably the most ambitious monument constructed during the Renaissance in Spain. Construction started in 1563 after King Philip II of Spain decided to commission a funerary monument for his father, the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V. But Philip II desired an even more complicated structure that would also function as a palace and monastery. By the time construction ended in 1584, the complex included not only these, but a church and college as well. A library was also added in 1592. The project was so complex that it took more than a decade to complete, and approximately a thousand people worked on it during its peak construction period.

A new Spanish severity

El Escorial is often described as severe or somber in appearance, with a symmetrically organized plan and a largely unornamented exterior. In its day, this was remarkable because it broke with architectural styles popular on the Iberian Peninsula, including the highly decorative Plateresque style, which was influenced by the ornate designs of silverwork.

The facade of the University of Salamanca, for instance, is a veritable feast for the eyes, with floral imagery, twisting vines, and medallions decorating the surface. El Escorial has none of this elaborate ornamentation.

The massive complex has four storeys, with large, rectangular towers at each corner. There are eleven courtyards, as well as three smaller “service” courts, and several gardens. Classical orders of columns punctuate the exterior, with massive, simple Doric columns on the façade. While there is little decorative or figural ornamentation, the west façade that marks the entrance to the Courtyard of the Kings (Patio de los Reyes) displays St. Lawrence (San Lorenzo) above the royal coat of arms, and the basilica’s facade includes six Old Testament kings towering above the first level.

The grid plan

The original layout of the complex was on a grid (sometimes referred to as a gridiron) plan laid out by Juan Bautista de Toledo, a student of Michelangelo who aided in the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. A grid plan suggests order and balance, clarity and unity. At El Escorial, some suggest that the grid plan possibly relates to the grill upon which St. Lawrence (San Lorenzo in Spanish) was martyred. Most Spanish cities on the Iberian Peninsula did not use the grid plan, in large part because they were older cities whose streets were already laid out. However, Philip II issued edicts in the sixteenth century that affected the construction of towns and cities in the Spanish viceroyalties that specified grid plans. This suggests a broader trend in Spain and its territories during the Renaissance of a return to cities laid out clearly and consistently—a nod to ancient Roman building practices.

A second architect, Juan de Herrera, completed the project after Toledo’s death in 1567. Herrera reportedly met with Philip II often to consult on the project, and the king appointed him as his royal architect towards the end of the 1570s. Herrera is known for his “severe” classicism, which was influenced by the Italian architectural forms of architects such as Sebastiano Serlio, Giacomo da Vignola, and Giulio Romano, whose work he observed on his travels to Italy. His design for El Escorial may have been especially influenced by Romano’s Palazzo Te in Mantua, which also incorporated classicizing architectural elements. El Escorial’s severe style is sometimes referred to as “Herreresque” in honor of Herrera.

Art at El Escorial

While the exterior is restrained in its decoration, many areas of the interior are elaborately decorated. Inside the basilica, more depictions of kings and saints await visitors. Frescoes adorn many of the surfaces, such as the walls of the library. Despite its highly decorative qualities, El Escorial’s interior is harmonious, with the ornamentation carefully planned to create a visually unified space.

Artists from different parts of Europe were hired to adorn the interior. Federico Zuccaro and Pellegrino Tibaldi were two Italian painters paid to complete frescoes and other paintings. Tibaldi’s Martyrdom of St. Lawrence on the main altarpiece in the basilica showcases the influence of Michelangelo, with its grandiose figures displaying well-defined musculature. We also find works by Claudio Coello, Luca Giordano, and El Greco. The latter produced The Martyrdom of St. Maurice for El Escorial in 1582, but Philip II apparently rejected it on claims that the the foreground figures were the focus of the composition.

During Philip II’s reign, El Escorial came to house many artworks, including some by Titian and others by Flemish painters like Hieronymous Bosch. The king eventually owned roughly twenty-six paintings by Bosch, many of which hung in El Escorial, including the artist’s famous Garden of Earthly Delights. Works that formed part of the royal collection at El Escorial eventually entered the Prado Museum’s collection.

A symbol of Imperial Spain

Philip encouraged those visiting him at court to journey to El Escorial. One particularly fascinating example dates to 1584 when Japanese nobles and their Portuguese Jesuit guide visited Philip II in Madrid, at which point the Spanish king brought them to El Escorial to delight in his project and hopefully impress them with its magnificence. Apparently it worked, as one record states that the Japanese nobles claimed it was “so magnificent a thing, whose like we have never seen or expected to see.”[1] One can imagine that the severe classicizing style combined with a grid plan helped to establish Philip II as akin to the great Roman emperors of the past, as well as a formidable imperial ruler with refined taste during the Renaissance.

[1] Henry Kamen, The Escorial: Art and Power in the Renaissance (New Haven: Yale University Press, 84).

Additional resources:

El Greco

El Greco, Burial of the Count Orgaz

A miracle at a burial