13.7.9: Northern Europe in the 16th century- Renaissance and Mannerism

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 88728

Northern Europe: 16th century

The Renaissance north of the Alps.

1500 - 1600 (Northern Renaissance and after)

An introduction to the Northern Renaissance in the sixteenth century

While the Renaissance was happening in Italy, great artistic and social changes occurred in Germany and the Low Countries.

A bias in favor of Italian art among earlier generalizations of scholars made Italy the focus of artistic invention and the Northern Renaissance a less sophisticated imitation of the real thing. One might debate whether the North experienced a Renaissance, but the artistic, institutional, and intellectual changes are evident.

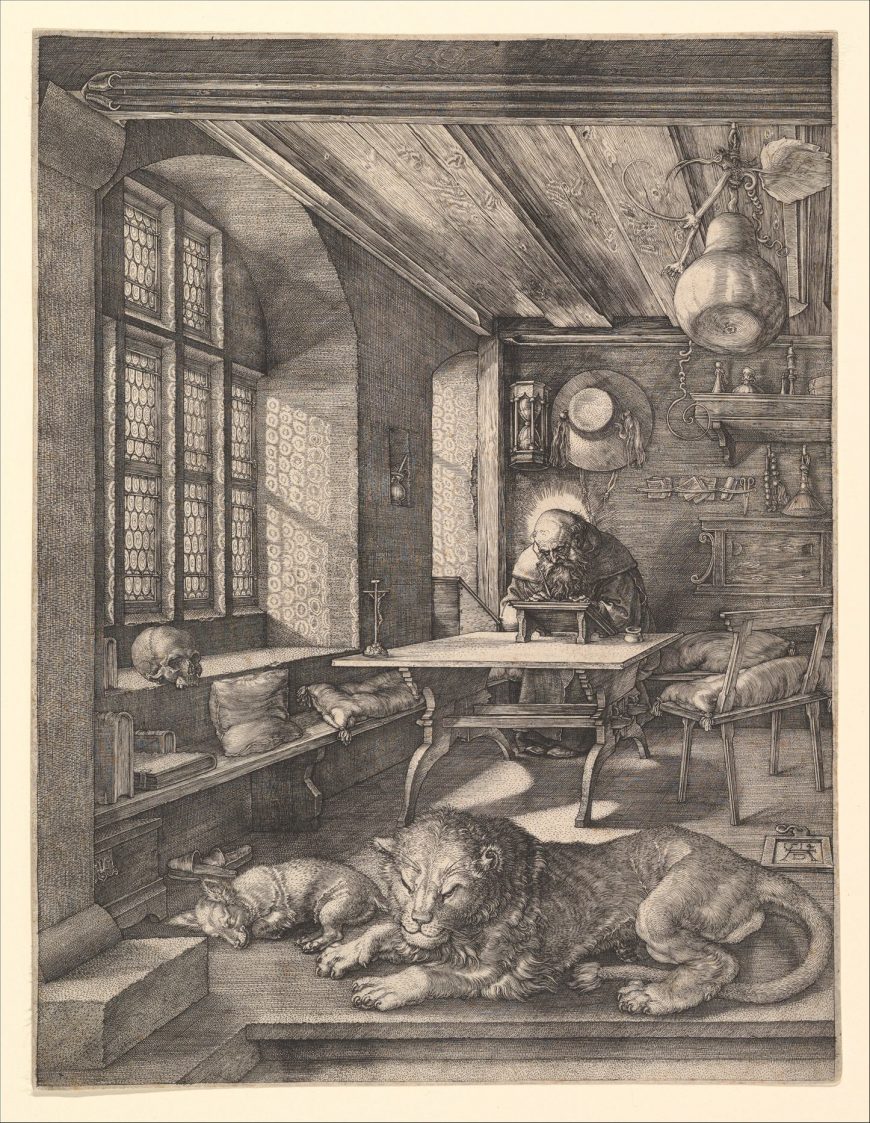

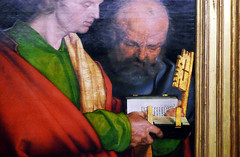

The 16th century: Dürer

Albrecht Dürer is the indisputable rock star of the German Renaissance. In addition to being a successful painter, Dürer built his reputation on his prints, both woodcut and engravings. Because prints can be made in multiples, he had an unusually broad audience. Mechanically reproducible media such as woodcuts and engraving not only helped Dürer disperse his ideas, they also made it possible for Northern artists to see Italian art without traveling.

Dürer likely had his first exposure to Italian art in Germany, in woodcut or engraved copies of Italian works. Looking at an Italian work of art in Germany may seem unremarkable to us. However, until prints were available all works of art were one of a kind, and the only way to see a new work of art was to travel. Prints were typically far less expensive than paintings and much lighter and therefore more portable. The switch from one-of-a-kind works of art to prints is in some ways comparable to the switch from buying or borrowing picture books to searching for images on Google.

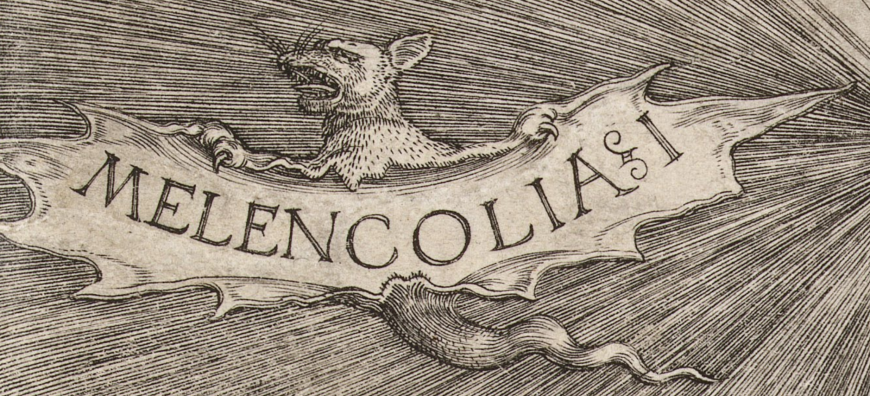

Dürer, Melencholia I

Among Dürer’s best-loved works is the engraving Melencholia I, 1514, which depicts the personification of melancholy, the temperament associated with artistic inspiration. The picture of the brooding figure, whose face resembles Dürer’s famous self portraits, may be male or female. Some scholars believe Dürer’s self portraits are androgenous. Though the face may be Dürer’s, the garment looks feminine.

Whatever the gender, the figure experiences the dreadful feeling of writer’s block. Surrounded by all the tools needed to create—a compass, a plane, nails—s/he sits still, head in hand, and does nothing. The wings are a painful reminder of our limitations. Gifted with intelligence, imagination, and the desire to soar, the figure’s small wings cannot lift such a weighty and substantial body. Bound up with the idea of frustrated creativity is the notion of creativity itself—which took on its present meaning during the Renaissance.

The space is like a fun house, never offering the viewer an opportunity to become oriented. Are we inside or outside? Where does the ladder start? Where does it lead to? The rhombohedron blocks the horizon, and all of the edges point out of the image, a seeming play of the logical system of horizon and orthogonal that create a unified space.

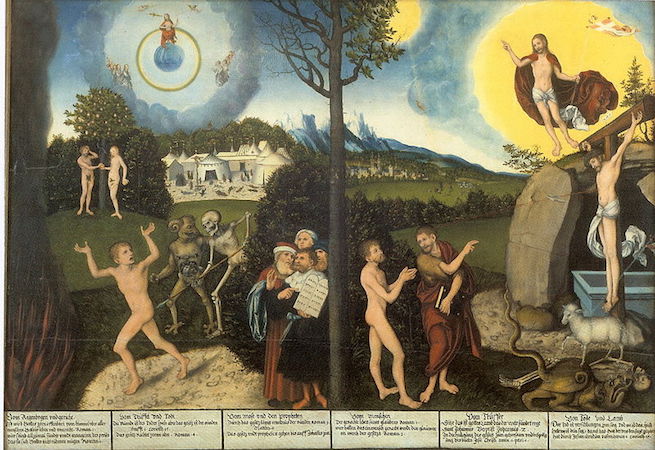

The printing press (images + text)

Perhaps the most influential aspect of the Northern Renaissance is the combination of printed image with text together in books. The printing press was invented in Germany around 1450. Until the printing press, books were laboriously copied and illustrated by hand, one at a time.

The combination of printed words and images created an explosion of information (rather like the change from typewriters to computers). The printing of books such as Luther’s translation of scripture and illustrated polemical pamphlets accelerated the Protestant Reformation, a movement that re-aligned religious and national boundaries, and ultimately would motivate migration to the New World.

Additional resources:

For instructors: related lesson plan on Art History Teaching Resources

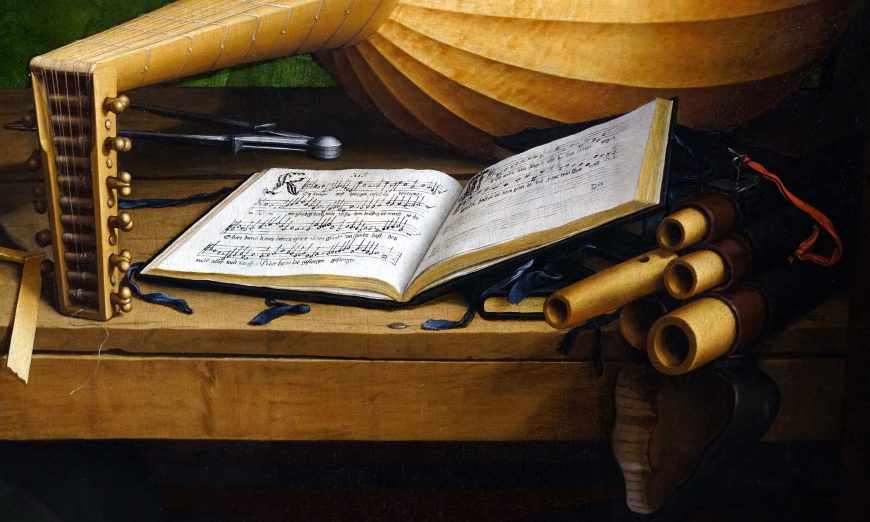

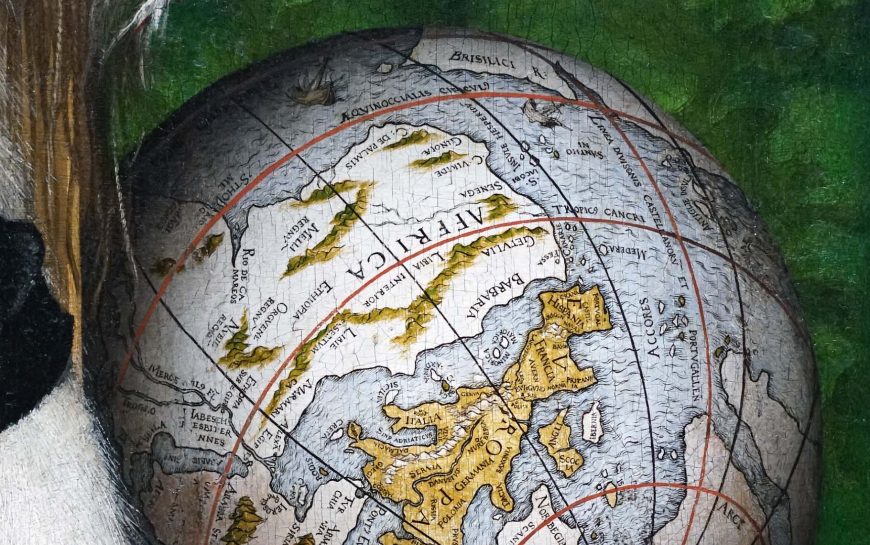

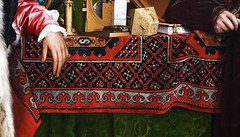

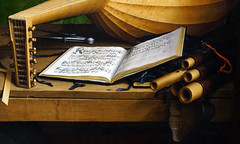

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Inventing “America” for Europe: Theodore de Bry

Theodore de Bry’s Collected travels in the east Indies and west Indies

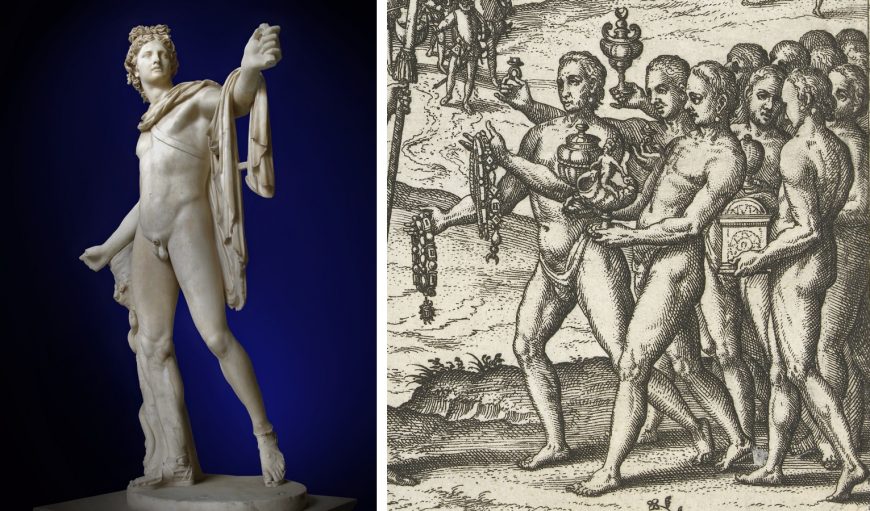

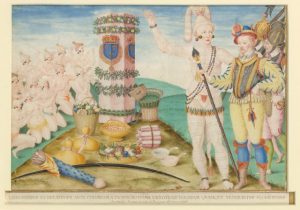

In the center of this image we see a finely-dressed Christopher Columbus with two soldiers. Columbus stands confidently, his left foot forward with his pike planted firmly in the ground, signaling his claim over the land. Behind him to the left, three Spaniards raise a cross in the landscape, symbolizing a declaration of the land for both the Spanish monarchs and for the Christian God.

Unclothed Taínos, the indigenous peoples of Hispaniola, walk toward Columbus bringing gifts of necklaces and other precious objects. Further in the background, on the right side of the print, other Taínos, with arms raised and twisting bodies, flee in fear from the Spanish ships anchored offshore.

This print from 1592, by the engraver Theodore de Bry, presents Columbus and his men as the harbingers of European civilization and faith, and juxtaposes them with Tainos, who are presented as uncivilized, unclothed, and pagan. This print, along with hundreds of others de Bry made for his 27 volume series, published over more than forty years, Collected travels in the east Indies and west Indies (1590–1634), affirm and assert a sense of European superiority, as well as invent for Europeans what America—both its land and its people—was like.

Though de Bry is most famous for his engravings of European voyages to the Americas (and Africa, and Asia), he never actually traveled across the Atlantic. It is not surprising then that de Bry’s depiction of the indigenous peoples of the Americas was a combination of the work of other artists who had accompanied Europeans to the Americas (artists were often brought on journeys in order to document the lands and peoples of the Americas for a European audience) as well as his own artistic inventions. For instance, he adapted (without credit) some of the images created by Johannes Stradanus, a well-known illustrator who created early images of the Americas. In his Collected travels in the east Indies and west Indies, de Bry republished (and translated into multiple languages) the accounts of others who had spent time traveling around the globe, and created more than 600 engravings to illustrate the volumes. The engraving above of Columbus and the Taínos comes from volume 4 of the Collected travels in the east Indies and west Indies. This volume reprinted the accounts of the Milanese traveler Girolamo Benzoni, who himself had drawn on the accounts of Columbus in his own writings.

The volumes of the Collected travels in the east Indies and west Indies that treat the voyages across the Atlantic to the Americas are known as the Grands Voyages, while the Petit Voyages (small voyages), were those to Africa and Asia.

Documenting America

De Bry’s copperplate engravings were among the first images that Europeans encountered about the peoples, places, and things of the Americas, even if he began making them almost a century after Columbus’s initial voyage. In the engraving with Columbus on the shoreline, the barely clothed Taínos resemble Greco-Roman sculptures, especially their poses and musculature. De Bry apparently had no interest in documenting the actual appearance of the Taínos.

De Bry’s Collected travels belongs to the genre of travel literature, which had been popular since the Middle Ages. Accounts of the Americas became wildly popular after Columbus’s first voyage. For example, Columbus’s 1493 letter to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabel (who had helped finance the voyage) was published in seventeen editions by 1497, and often included woodcuts depicting select moments of his voyage.

De Bry and his audiences

De Bry was a Protestant, and fled Liège (today in Belgium) where he was born to avoid persecution. He made his way to Frankfurt, which is where he started work on Grands Voyages. After his death in 1598, his family continued his work and finished the remaining volumes in 1634. Interestingly, different versions of the Grands Voyages catered to different Christian confessional groups. The volumes in German were geared towards Protestants, while those in Latin appealed to Catholics. De Bry created images that he could market to either audience, but he made changes to the texts to appeal more to either Catholics or Protestants. Psalms that Calvinists felt encapsulated their beliefs or longer passages criticizing Catholic beliefs or colonial practices were omitted from Latin versions, which were often filled in with more engravings duplicated from other parts of the text.

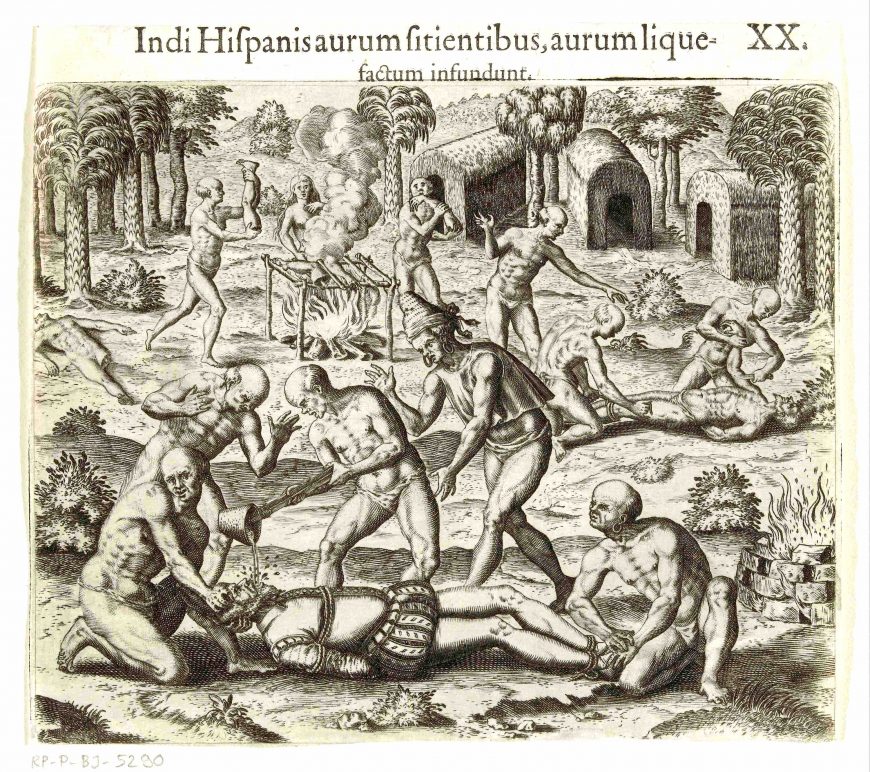

General subjects of the Grands Voyages engravings

While some of de Bry’s prints in Grands Voyages focus on the exploits of famed European navigators like Columbus, others show indigenous groups and their customs. Some of these images display the atrocities that occurred in the wake of Europeans’ arrival, violent conquest, and colonization. Indigenous peoples are fed to dogs, hanged, or butchered. Still others depict native responses to the European invasion, such as drowning Spaniards in the ocean or pouring liquid gold into invaders’ mouths.

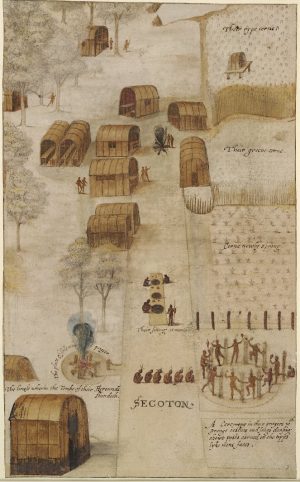

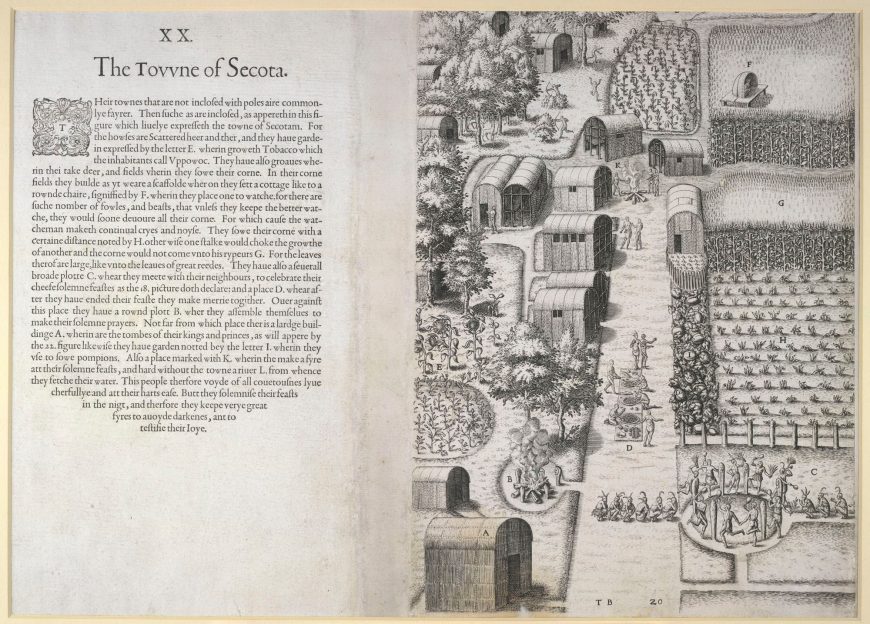

Travels to Virginia

The Grands Voyages (the section on cross-Atlantic voyages) begins with a reprint of an earlier text by the English colonist Thomas Hariot, A Brief and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia (1590). It also includes translations of this text into Latin, German, and French. De Bry’s accompanying engravings were based on watercolors by John White, who had settled on Roanoke Island, North Carolina in 1585 and who had created paintings while there. His watercolors document clothing, dwellings, and rituals of the eastern Algonquian peoples.

Even though Virginia and North Carolina were colonized by Europeans after they had seized other areas in the Americas, de Bry placed them in the first volume of his Grands Voyages. This may be because he had visited London just after Hariot’s book was published in 1588, and was given both that text and the watercolors of White. De Bry was clearly not interested in a providing a chronological account of European exploration and colonization.

One of White’s paintings represents the town of Secoton, with people going about their daily life activities. In the right foreground people dance in a circle. Corn grows in neat rows. Dwellings line a road. In his engraving, de Bry made several changes to White’s watercolor. He expanded the village and removed the textual inscriptions that identified important features of the village (instead incorporating a separate key).

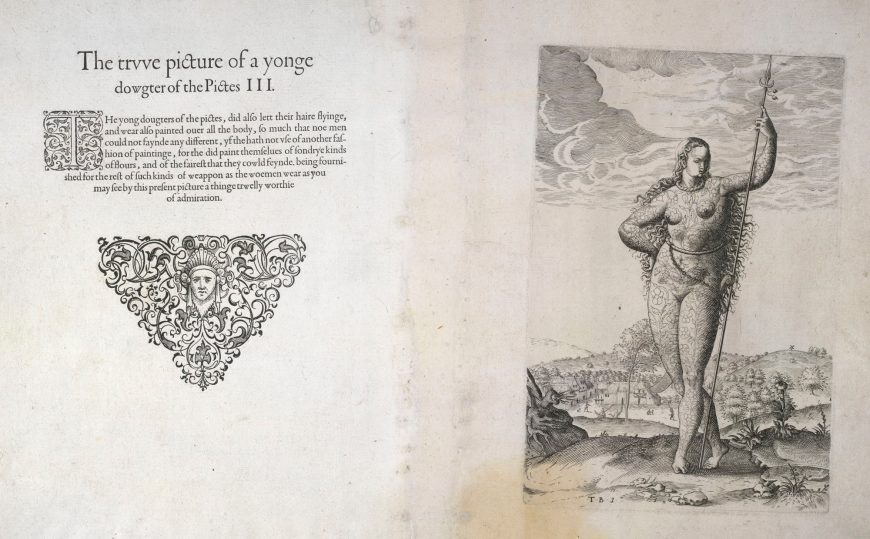

For his engravings, de Bry also transformed watercolors White had created of Scottish Picts (an ancient pagan indigenous peoples of Scotland who lived in a loose confederation of groups and who painted their bodies). But why include a discussion of Picts in a book on the Americas?

Hariot’s text states that “Some picture of the Picts which in the old time did inhabit one part of the great Britain,” which according to him “show how that the inhabitants of the great Britain have been in times past as savage as those of Virginia.”[1] White compares them to the Algonquian peoples to suggest that Europe has its own history of uncivilized, pagan people. Despite attempting to reconcile the Algonquian peoples with the Picts in Europe, the manner in which he compares them—as savages—speaks to a presumed European superiority.

Travels to Florida

Volume 2, published in 1591, focused on French voyages to Florida, and was based on the accounts of the French colonist René Goulaine de Laudonnière. De Bry created engravings based on the watercolors of Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues, who was part of the French expeditions to Florida that were headed by Jean Ribault in 1562 and Laudonnière in 1564. One of the engravings adapted from Le Moyne’s watercolors shows the Timucua worshipping a column that had supposedly been erected by Ribault. The most prominent figure, identified as chief Athore, stands next to Laudonnière, who has followed him to see the sight. The other Timucua kneel, while raising their arms in gestures of reverence in the direction of the column, itself decorated with garlands. Before it, offerings of food and vegetables abound. De Bry made several notable changes to the print, such as adjusting Athore’s features to look more European, with raised cheekbones and an aquiline nose. Le Moyne’s earlier watercolor had also Europeanized the Timucua peoples: he paints them with the same complexion as Laudonnière, but with even blonder hair.

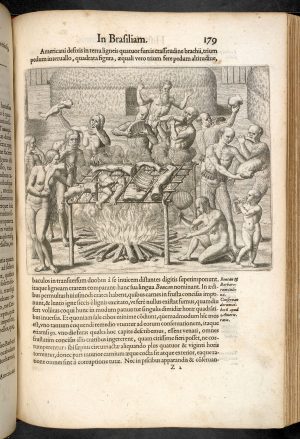

Cannibalism in Brazil

Cannibalism was (and remains) commonly associated with certain indigenous peoples of the Americas. In de Bry’s series, his third volume recounted Hans Staden’s experiences of cannibalism in Brazil. De Bry’s engravings for this volume were among the most well-known in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century, in large part because of their gruesome and sensationalistic character. Note that de Bry’s print, “Indians pour liquid gold into the mouth of a Spaniard,” may also depict cannibalism among the figures shown in the background.

Staden, a German soldier who traveled to South America, had been captured in 1553 by the Tupinambá, an indigenous group in Brazil. After his return to Europe in 1557, he wrote about Tupinambá customs, family life, and cannibalism, describing how the Tupinambá practiced it ceremonially, especially eating their enemies. Staden’s initial book included simple woodcuts, but de Bry’s updated engravings proved far more popular and enduring in the European cultural imagination. Perceptions of indigenous Brazilians were shaped by these images, and reinforced the notion that the Tupinambá, and others like them, were depraved, primitive, and sinful.

One of his images depicts naked adults and children drinking a broth made from a human head and intestines, visible on plates amidst the gathering of people. Another depiction of the Tupinamba shows a fire below a grill, upon which body parts are roasted. Figures surround the grill, eating. In the back is a bearded figure, most likely intended to be Staden. Hand-colored versions of de Bry’s prints emphasize the disturbing subject of the images even more.

Cannibalism would come to be closely associated with peoples of the Americas. De Bry would even use images of cannibals to serve as the engraved frontispiece to volume 3. Showing the Tupinambá eating human flesh exoticized them, and justified European control.

Other volumes and the legacy of de Bry

The fourth, fifth, and sixth volumes of the set focus on Girolamo Benzoni’s accounts, such as Historia Mondo Nuovo, with part 6 discussing the atrocities committed against the indigenous population of Peru. Parts 7 to 12 incorporated the travel accounts of Ulricus Faber, Sir Francis Drake and Walter Raleigh, José de Acosta, Amerigo Vespucci, John Smith, and Antonio de Herrera among others. Like the volumes that came before them, de Bry provided numerous images to increase readers understanding of the narratives.

The Grands Voyages, and the entire Collected Travels, relate more generally to the forms of knowledge and collecting popular at the time. Like a cabinet of curiosity, de Bry’s project organized information in text and images so that readers could come to know the Americas. The volumes seek to provide encyclopedic knowledge about the Americas, much as the objects did in a curiosity cabinet. De Bry’s many prints were important resources for Europeans who sought to better understand the Americas. It allowed readers to take possession of these distant lands and peoples, where they could become participants in the colonial projects then underway, allowing them to feel a sense of dominance over the peoples and lands across the Atlantic—lands which many in Europe would never see firsthand. These often inaccurate images and narratives supported a sense of superiority, with Europeans positioned as more civilized and advanced, and the American “others” as less so. De Bry’s images of America would cement for Europeans a vision of what America was like for centuries to come.

[1] “Some Pictvre of the Pictes which in the olde tyme dyd habite one part of the great Bretainne,” which according to him “showe how that the inhabitants of the great Bretainne haue been in times past as sauuage as those of Virginia.” 67. Thomas Hariot, with illustrations by John White, A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia (1590).

Additional resources:

Picturing the New World: The Hand-Colored de Bry Engravings of 1590

White Watercolors and de Bry engravings, on Virtual Jamestown

De Bry engravings of the Timucua, on Florida Memory

Columbus reports on his first voyage, 1493

Kim Sloan, ed., European Visions, American Voices, British Museum Research Publication 172 (2009).

Bernadette Bucher, Icon and Conquest: A Structural Analysis of the Illustrations of de Bry’s Great Voyages (Chicago: U of Chicago Press, 1981).

Michael Gaudio, Engraving the Savage: The New World and Techniques of Civilization (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008).

Stephen Greenblatt, Marvelous Possessions: The Wonder of the New World (Chicago: U of Chicago Press, 1991).

Michiel van Groesen, “The de Bry Collection of Voyages (1590–1634): Early America reconsidered,” Journal of Early Modern History 12 (2008), pp. 1–24.

Michael van Groesen, Representations of the Overseas World in the de Bry Collection of Voyages (1590–1634) (Leiden: Brill, 2008).

Maureen Quilligan, “Theodore de Bry’s Voyages to the New and Old Worlds,” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 41, no. 1 (Winter 2011): 1–12.

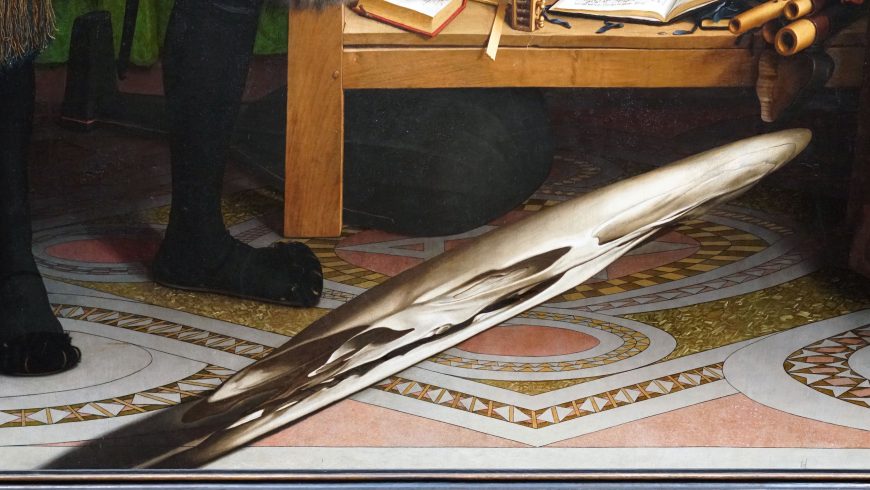

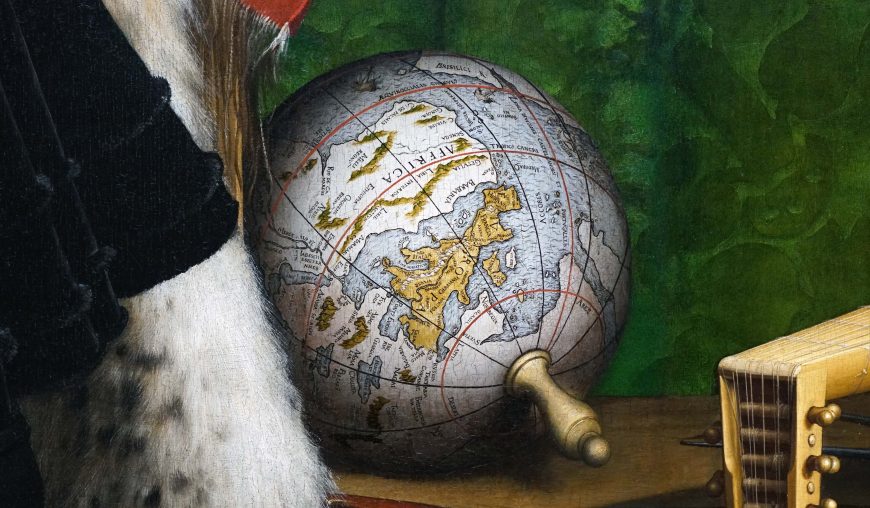

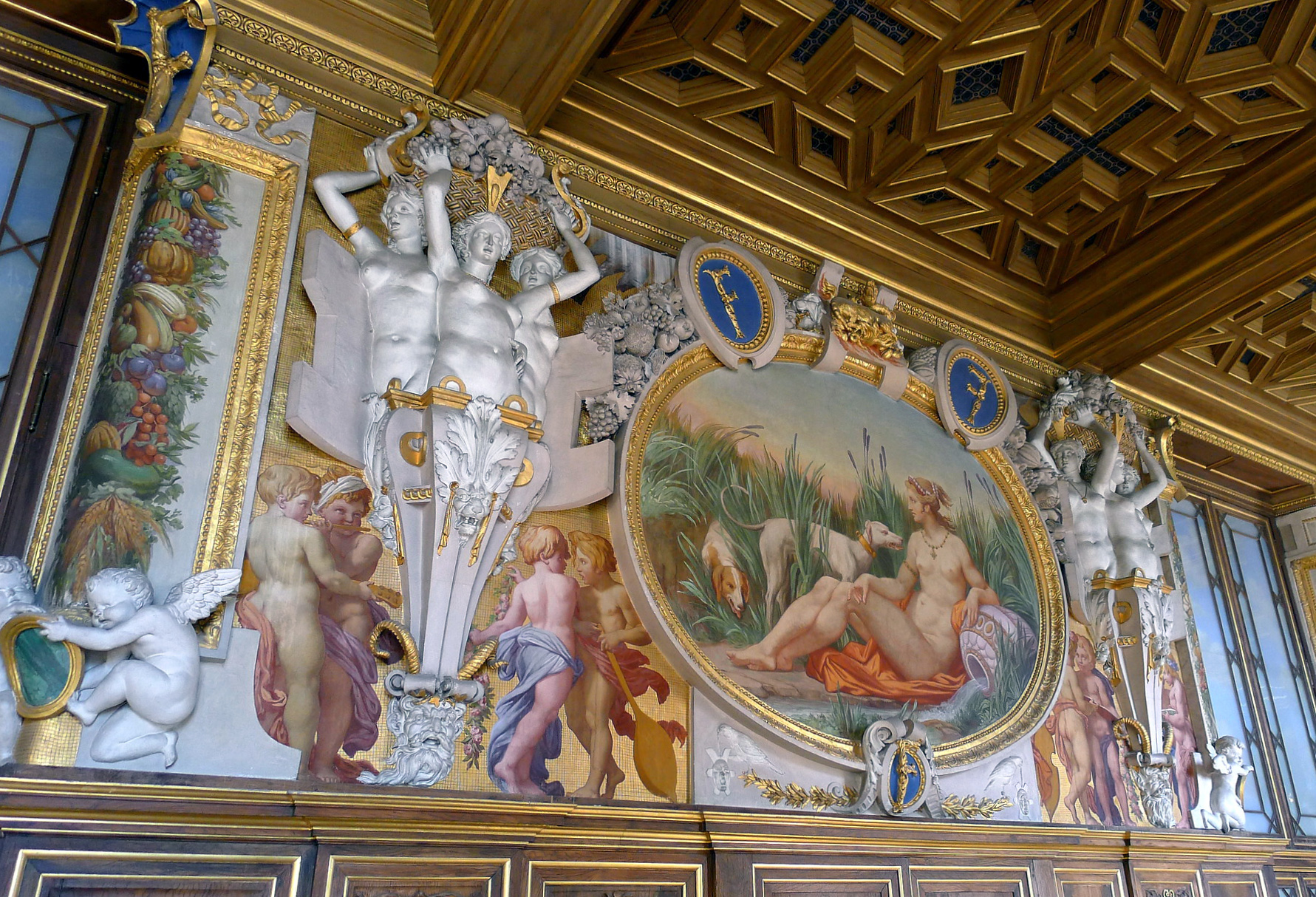

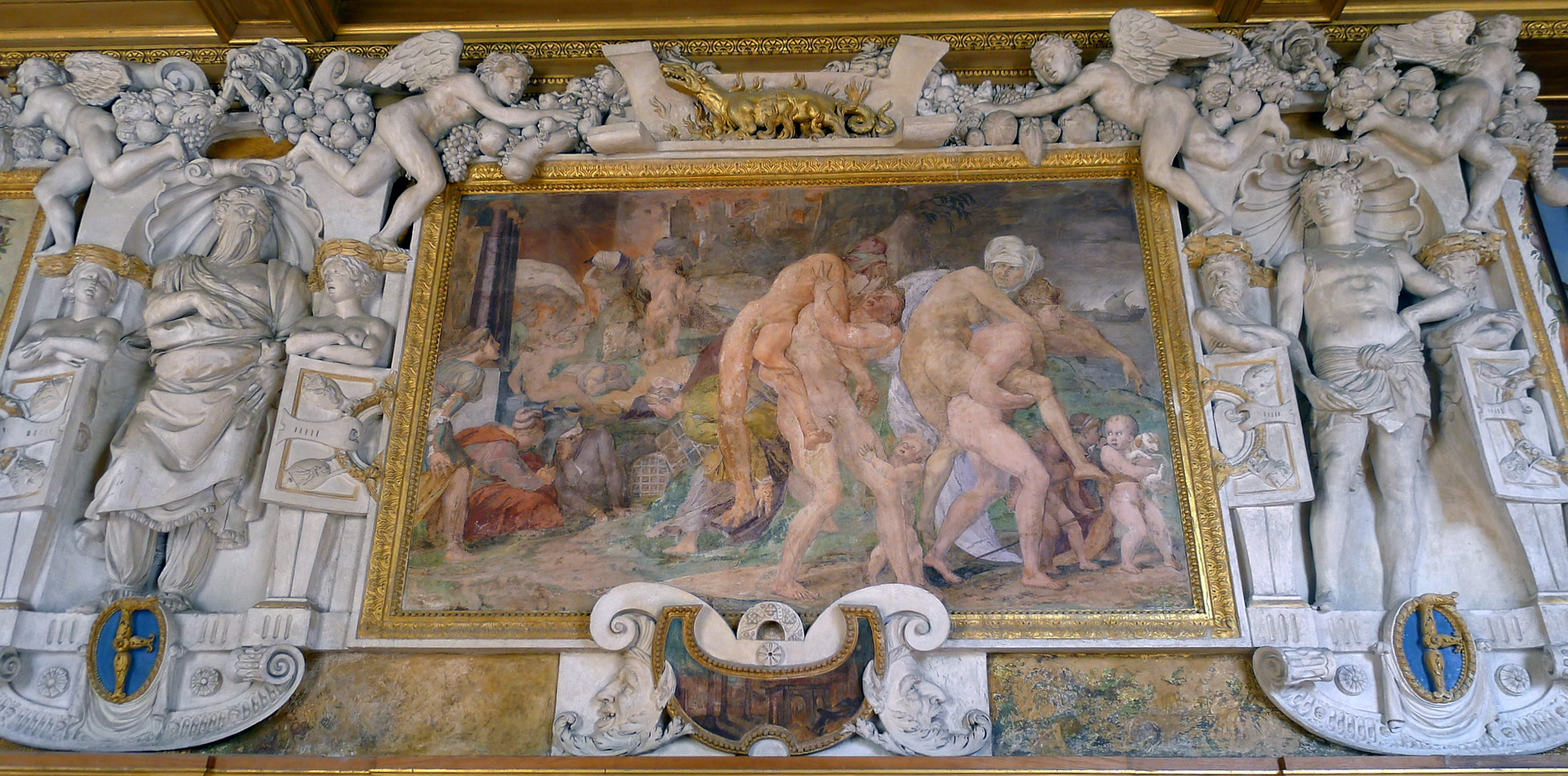

Johannes Stradanus and Theodoor Galle, “The Discovery of America”

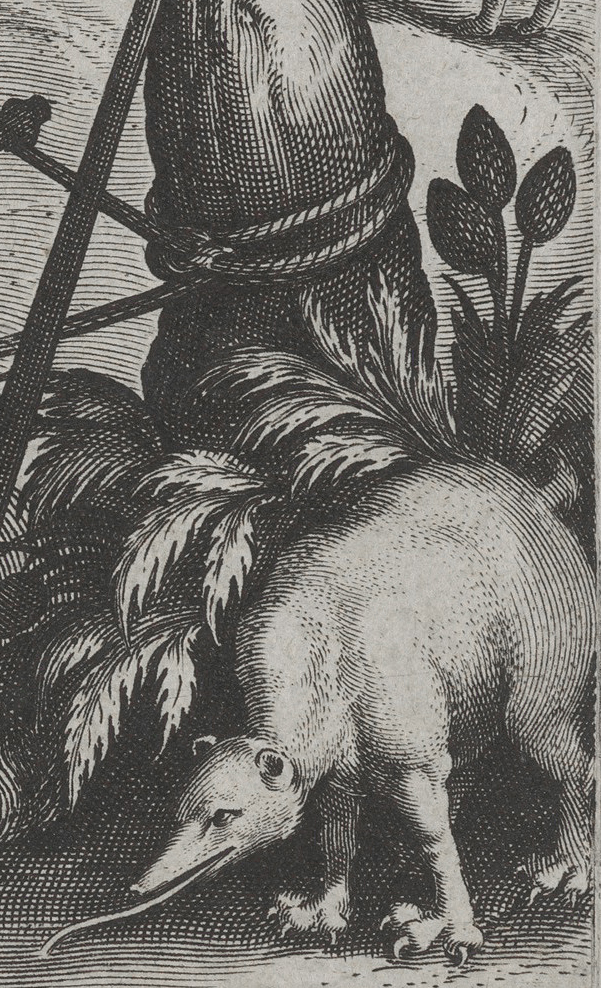

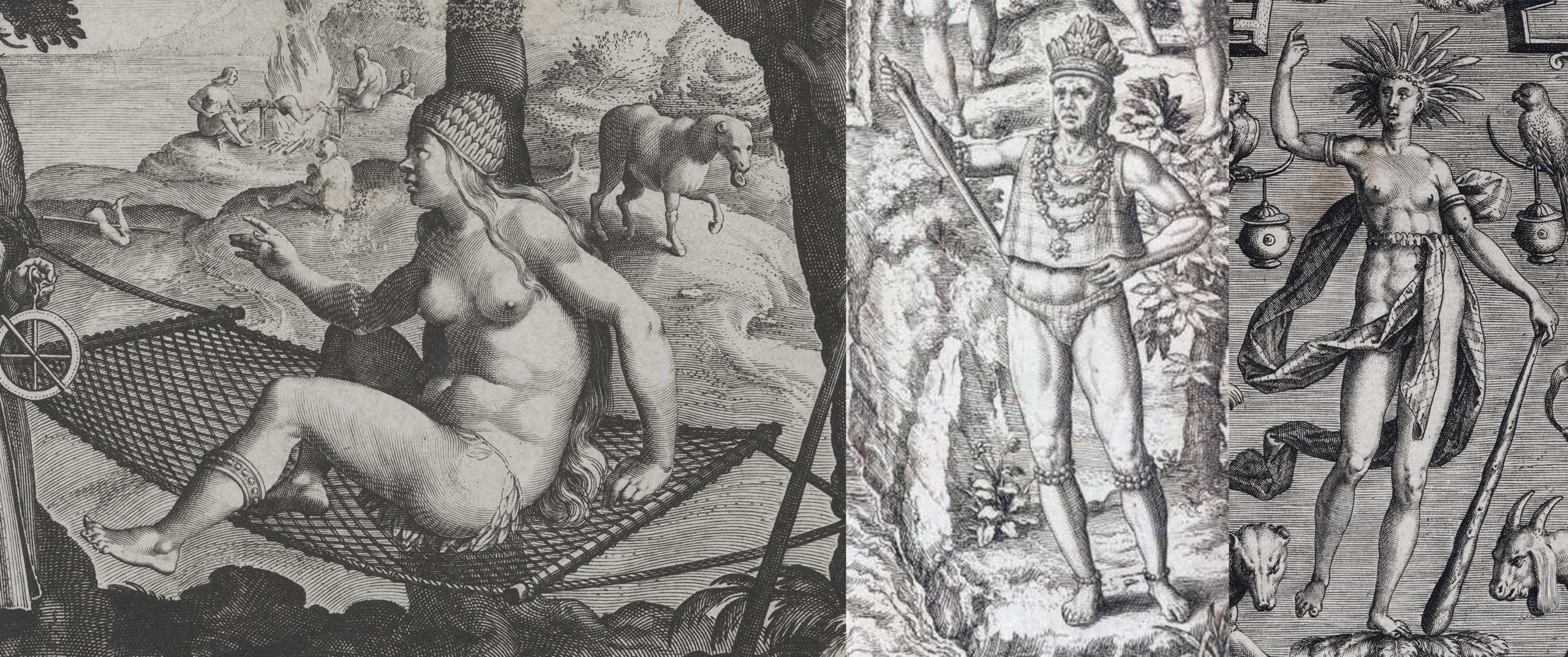

In an engraving from around 1600, a nude woman reclines on a hammock while a standing, dressed man approaches her. She is a personification of America, while he is Amerigo Vespucci, the Florentine navigator who would give his name to the Americas. The scene, called “Discovery of America,” was first drawn by Netherlandish artist Johannes Stradanus in the 1580s. It was then transformed into a print series that formed part of Nova Reperta, or New Inventions and Discoveries of Modern Times (c. 1600). This scene is the most famous of that series, appearing first among twenty engraved plates.

Vespucci and a Personification of America

In the print, as the original ink, Vespucci wears a cape over his armor. A sword hangs at his side. In one hand he holds a navigational instrument (an astrolabe) while in the other he holds a banner with a crucifix at the top. To his left are the ships he commands, one ashore and the other sailing towards the Brazilian coastline. His presence seems to wake or perhaps startle the woman. While she is nude, she does wear an array of accessories, including a feathered cap and loincloth, and metal anklets (likely made of gold). A weapon, perhaps a club, rests against a nearby tree.

Surrounding her in the fore- and middle ground are animals, such as a sloth hanging from a tree, an anteater beside her club, and a tapir behind her shoulder, while in the background naked people roast human body parts over a fire. Pineapples grow on stalks just behind the anteater, appearing more like pinecones than fruit. It is clear that Stradanus never actually saw these plants or animals firsthand.

Stradanus contrasts the European and American figures and the worlds they signify. Vespucci is clothed, while America is not. He stands, she sits. He holds his banner upright, while her club is set aside. He comes from the sea, she comes from the land. His world has ships and navigational instruments, hers wild animals and cannibals. His body is obscured, while hers is available and sexualized.

These juxtapositions encourage viewers to make particular associations. Vespucci represents order and those that are civilized, while America symbolizes disorder and the uncivilized. His ships, sword, and astrolabe are also the instruments of exploration and conquest, used to subdue those people perceived as inferior. Stradanus portrays America and the cannibals behind her in the nude to underscore their primitive nature.

Who made this engraving?

An inscription is included that tells us who participated in making made the engraving. “Ioan. Stradanus inuent. / Theodor. Galle sculp. / Ph[i]l[ip]s Galle execud.” This means that Johannes Stradanus designed the image, Theodoor Galle engraved it, and Philips Galle distributed it.

Stradanus, originally Jan van der Straet, was born in Bruges (now in Belgium), in 1523. He eventually moved to Florence where he died in 1605. More than eighty years after Vespucci’s Mundus Novus (New World) was first published in 1503, Stradanus produced his drawing, which was then engraved in Antwerp by Theodoor Galle at the workshop of Philips Galle. This collaborative practice was common among printmakers in the early modern period.

Stradanus and new inventions

Besides the “Discovery of America,” Stradanus illustrated a number of other inventions and discoveries that were then transformed into engravings for Nova Reperta. In one, called “Color Olivi” (“Oil Paint”), he included the famous netherlandish artist Jan van Eyck in his workshop, preparing and using oil paint. Other plates credit Europeans with inventing printing, the compass, and gunpowder (despite their having all come from China originally). We can understand these engravings as participating in a broader message tying together European colonization, invention, and superiority.

The inscriptions in the engraving of America also reference these same ideas. The title is written as “America,” and more Latin text that says “Americen Americus retexit, et Semel vocauit inde semper excitam.” The first part translates as “Americus rediscovers America,” implying that Amerigo Vespucci has discovered America with fresh eyes after Christopher Columbus, who believed he had found Asia.

The “new world”

Vespucci had originally explored the Americas in two separate voyages, between 1499 and 1501, and Mundus Novus included the correspondence he supposedly wrote with Lorenzo Pietro di Medici, his patron. This correspondence might have been somewhat fictionalized. Nevertheless, it was in these letters that Vespucci first refers to the Americas as mundus novus, or “new world,” one that was not part of Asia as Christopher Columbus had claimed. This name, “new world,” has, unfortunately, stuck, privileging the European viewpoint over that of the millions of indigenous peoples who already lived on the American continents.

Inventing the “Indio” and “America”

When Christopher Columbus accidentally bumped into the Caribbean in 1492, he believed he had reached the Indies (India and Southeast Asia). As a result, the lands he encountered were named the ‘Indies’ and the peoples, indios. This misnomer of indio (Indian) wrongfully labeled the incredibly diverse groups of people not only of the Caribbean, but throughout all of what would come to be called the Americas. The name of indio aided in a process of homogenization of the peoples of this land. The term indio, at least early on, also served to differentiate those who were Christian from those who were not. Stradanus’s print participates in this homogenization. America is represented by a female personification, not specific individuals.

Earlier publications about the Americas had few illustrations, so printmakers like Stradanus felt free to invent imagery within their engravings and to borrow figures and motifs from other artists. We find many of the same visual motifs associated with America in prints by Stradanus and the artists Theodor de Bry and Marcus Gheeraerts (among others).

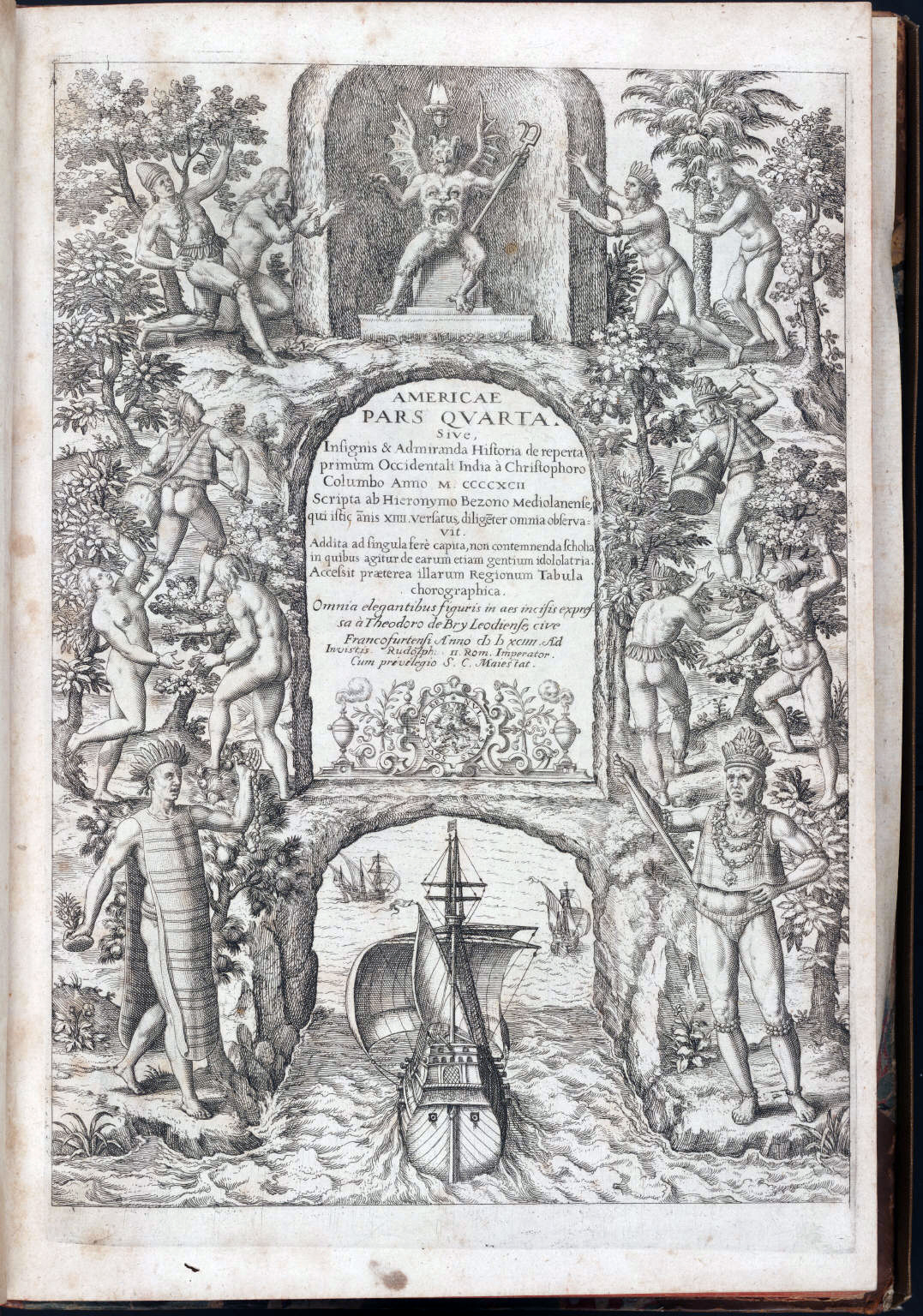

On the title page to volume four, called Americae, of his Collected travels in the east Indies and west Indies, de Bry places the title in the center of a rounded-arch doorway. Above it, a demonic idol, complete with bat wings, mask-like face, and monstrous visage on its abdomen, sits on a throne. This purports to represent one of the deities of Amerindians. Below the title is a ship, sailing through a similarly shaped archway to join two other smaller ships. They represent the ships of Columbus, and we can read their passage through the arch as their departure from Europe as they embark on their voyage to the Americas. Flanking the center register are a variety of indigenous peoples of the Americas, identifiable by what they do (or don’t) wear. Many of them are unclothed, while others wear simple loincloths and feathered headdresses. The two largest figures stand flanking the ships. One wears a long tunic and feathered headdress, while the other wears a crown, cropped tunic, large chains around his neck, and a loincloth. He holds a staff (or club) on his hip while standing in contrapposto. All the figures are idealized, with well-defined musculature that makes them look like Greco-Roman sculptures. We also find palm trees and other flora that help to locate the scenes in an American context.

In Marcus Gheeraerts’s engraving of America, we see a barely dressed woman standing in contrapposto in the center of the composition. An elaborate feathered headdress rests on her head and she holds a club. Surrounding her are other be-feathered individuals, along with parrots, mammals like a tapir, two Inuits at the lower corners (based on drawings by John White), and even fantastical creatures–all of which draw from the same symbol set to portray the Americas.

As is clear from looking at these engravings, printed media played a crucial role in providing Europeans with information about the Americas in the early modern period. Stradanus’s print attests to the important role that iconography played in creating a defined set of symbols that would communicate to European viewers specific perceptions about America as exotic and primitive for centuries to come.

Additional resources

Read more about Stradanus’s “Discovery of America”

Read more about Collaert’s “Invention of Oil Painting”

Daniela Bleichmar, Visual Voyages: Images of Latin American Nature from Columbus to Darwin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017)

Benjamin Schmidt, Innocence Abroad: The Dutch Imagination and the New World, 1570–1670 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001)

Jose Rabasa, Inventing America: Spanish Historiography and the Formation of Eurocentrism (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1993)

Michael Gaudio, Engraving the Savage: The New World and Techniques of Civilization (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008)

Lia Markey, “Stradano’s Allegorical invention of the Americas in Late Sixteenth-Century Florence,” Renaissance Quarterly 65, no. 2 (2012): pp. 385–442

Netherlands

"Netherlands" means "low countries,” and refers to the area’s low elevation, largely at or below sea level.

1500 - 1600

Hieronymus Bosch

Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights

“But I don’t want to go among mad people,” Alice remarked.

“Oh, you can’t help that,” said the Cat: “we’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.”

“How do you know I’m mad?” said Alice.

“You must be,” said the Cat, or you wouldn’t have come here.”—Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

Deciphering the indecipherable

To write about Hieronymus Bosch’s triptych, known to the modern age as The Garden of Earthly Delights, is to attempt to describe the indescribable and to decipher the indecipherable—an exercise in madness. Nonetheless, there are a few points that can be made with certainty before it all unravels.

The painting was first described in 1517 by the Italian chronicler Antonio de Beatis, who saw it in the palace of the counts of Nassau in Brussels. It can therefore be considered a commissioned work. The fact that the counts were powerful political players in the Burgundian Netherlands made the palace a stage for important diplomatic receptions and the work must have caused something of a sensation with its viewing audience, since it was copied, both in painting and tapestry, after Bosch’s death in 1516.

We can assume, therefore, that Bosch’s bizarre lexicon of human congress must have held some appeal, or some meaning, for a contemporary audience. In a period marked by religious decline in Europe and, in the Netherlands, the first blush of capitalism following the abolition of the guilds, the work has often been interpreted as an admonition against fleshly and worldly indulgence, but that seems a rather prosaic purpose to assign to a highly idiosyncratic and expressively detailed tour-de-force. And, indeed, there is very little agreement as to the precise meaning of the work. It is a creation and damnation triptych, starting with Adam and Eve and ending with a highly imaginative through-the-looking glass kind of Hell. No one really knows why Bosch imagined the world in this particular way.

Here’s what I think. What concerned Bosch, in his triptych of creation, human futility and damnation (the Garden of Earthly Delights is a modern misnomer for the work), was the essentially comic ephemerality of human life. Allow me to explain.

The outer panels

When the triptych is in the closed position (above), the outer panels, painted in grisaille (monochrome), join to form a perfect sphere—a vision of a planet-shaped clear glass vessel half-filled with water, interpreted to be either the depiction of the Flood, or day three of God’s creation of the world (which has to do with the springing forth of flowers, plants and trees, in which case he’s guilty of heedless over-watering).

A tiny figure of God, holding an open book, is found in the uppermost left corner of the left panel, and the inscription that runs along the top of both panels can be translated to read “For he spoke, and it came to be; he commanded, and it stood firm,” which is from Psalm 33.9. If one thinks of the outside panels as the end of the entire pictorial cycle, rather than its beginning, then this image could easily be a depiction of the Flood, sent by God to cleanse the earth after it was consumed by vice.

This path towards vice is mapped in the inner panels of the triptych. The outer panels are therefore intended to provoke meditative purgation, a cleansing of the mind. It should be pointed out that this work, like Bosch’s Hay Wain triptych (also framed by a creation and damnation scene), is a triptych only in form; neither depict the conventional arrangement of a tripartite altarpiece because their center panels do not include religious figures or even religious scenes. What Bosch seems to have invented is an entirely new form of secular triptych, one that functioned kind of like a Renaissance home theater package for wealthy patrons.

The first panel: God Introduces Eve to Adam (and all hell breaks loose)

The first panel depicts God, looking like a mad scientist in a landscape animated by vaguely alchemical vials and beakers, presiding over the introduction of Eve to Adam (which, in itself, is a rather rare subject). Although they are precisely located in the center foreground, in scale Adam and Eve—as well as God—are precisely as important as the other creatures in this paradisiacal garden, including an elephant, a giraffe (straight out of Piero de’ Cosimo) a unicorn and other more hybrid and less recognizable animals, along with birds, fish, other aquatic creations, snakes and insects.

The introduction of woman to man, in this setting, is clearly intended to highlight not only God’s creativity but human procreative capacity. In the hierarchy of God’s handiwork, Adam and Eve represent his most daring achievement, as though after he’d made everything else he thought he needed to leave a signature on the world in which he could recognize himself. It’s a matter of conjecture, when one proceeds to the central panel, as to whether Bosch is saying that the creation of man, on whom God conferred free will, might have been a divine mistake.

The central panel: People nakedly cavort (and all hell breaks loose)

This is the panel from which the title Garden of Earthly Delights was derived. Here Bosch’s humans, the offspring of Adam and Eve, gambol freely in a surrealistic paradisiacal garden, appearing as mad manifestations of a whimsical creator—sensate cogs of nature alive in a larger, animate machine. It is a matter of divided opinion as to what, exactly, the humans are actually doing in this delightful, dense and nonsensical landscape, alive with a dizzying array of some of Bosch’s most delectable creatures and dotted with his alembic architecture. It is almost as though he imagined the world of creation as a terrific Willy Wonka series of machines with humans as their product.

Given Bosch’s emphasis on nude figures, some of which are engaged in amorous activities —although none in flagrante—this central scene has often been interpreted as a warning against lust, particularly in conjunction with the third panel, depicting Hell (the Spanish Hapsburgs, in fact, referred to the work as “La Lujuria” — lust). I wonder though. Bosch’s depiction of humans cavorting in the elemental world of God’s creation, seems, to me, less inculpatory than simply a commentary on the fact that there’s little to differentiate man from animals from plants.

Many figures appear in all sorts of chrysalis states, or inside eggs or shells, and are fed ripe berries by birds or strange hybrid creatures; in the middle-ground some kind of procession of men, riding on various animals and accompanied by birds, circles a small lake of bathing maidens. It’s true that some unlikely human orifices are stuffed with flowers, but there is no explicit sex in this panel—just a gluttonous consumption of varieties of berries that have, by some, been linked to the pervasively hallucinogenic atmosphere (magic berries instead of magic mushrooms). In the end, there is folly and there is much that is visceral, but there’s no real vice.

Instead, what Bosch appears to be doing is contemplating man’s place in the greater divine machine of nature. Maybe he’s saying, as Lucretius did, that all matter is made of atoms that come together for a time to form a sensible thing and, when that thing dies, those atoms return to their origins to reconfigure in some other form. This breaking and becoming is the nature of nature, and man in nature, is not differentiated by anything OTHER than his free will, his concern for his own behavior. Our reason is our undoing. Every man’s hell is only what he can imagine, and Bosch was more imaginative than most. His was a highly singular and idiosyncratic talent, and Bosch was really no more a product of his own time than he would have been of any other time. However, his ability to visualize hallucinatory landscapes made him extremely popular, three centuries later, with surrealists like Salvador Dali, who was also a virtuoso imagineer of nightmarish other-worldly worlds. I would venture to guess that Lewis Carroll must also have been a fan.

The third panel: Finally, all hell breaks loose

Bosch saves the best for last. Earlier visions of Hell, if indeed that’s what Bosch intended here, are pretty tame in comparison to this. Against a backdrop of blackness, prison-like city walls are etched in inky silhouette against areas of flame and everywhere human bodies huddle in groups, amass in armies or are subject to strange tortures at the hands of oddly-clad executioners and animal-demons.

Dotted about are more crazy machine-like structures that seem designed to process human flesh. Some of these are strikingly disturbing. Near the center, a bird-like creature seated in a latrine chair, like a king on a throne, ingests humans and excretes them out again; nearby a wretched human is encouraged to vomit into a well in which other human faces swirl beneath the water.

In general, the bodies purge themselves or are purged of demons, black birds, vomitus fluids, blood; as in any good Boschian world, bottoms continue to be prodded with various instruments. But the general emphasis is on purgation.

Overall, there is a marked emphasis on musical instruments as symbols of evil distraction, the siren call of self-indulgence, and the large ears, which scuttle along the ground although pierced with a knife, are a powerful allusion to the deceptive lure of the senses. In fact, many of the symbols and the tortures here are pretty standard in the catalogue of the Seven Deadly Sins, in which our senses deceive our thoughts into self-indulgent over-consumption.

One key element here, however, requires some explication—the central, Humpty-Dumpty-ish figure who gazes out of the scene, his cracked-shell body impaled on the limbs of a dead tree. The art historian Hans Belting thought this was a self-portrait of Bosch, and a lot of people believe this, but it’s impossible to verify. Still, it quite strikingly illustrates the presence of a controlling, human consciousness in the centre of all this tortured imagining. And this is where my interpretation parts ways with those who have come before.

Because, while “Bosch’s” mind (if it is a self-portrait) might be distracted with thoughts of lust, symbolized by the bagpipe-like instrument balanced on his head (standard phallic stand-in), within the hollow of his body, a tiny trio of figures sit at a table as though dining. To me, these three figures are reminiscent of Genesis 18.2, in which God arrives at the door of Abraham, accompanied by two angels (all disguised as ordinary men) and Abraham, without question, offers them his humble hospitality. As his reward, God bestows a miraculous pregnancy on the aged Abraham and Sarah, declaring that, through this act, Abraham will father God’s chosen tribe on earth. This would also be consistent with Psalm 33.12: “ Blessed is the nation whose God is the LORD, the people he chose for his inheritance.” God then sends his angels (who are kind of early incarnations of FBI agents) to investigate matters in Sodom and Gomorrah, and Abraham uses this opportunity to intervene with God on behalf of the wickedness of the people there: “Will you sweep away the righteous with the wicked?” he asks.

It seems to me that this is the question the whole triptych asks—whether God, having made the world and having conferred on man both the blessing and the curse of free will, would destroy all of his creation in the face of human failing. This is the fundamental connection between these inner panels and the destructive flood depicted on the outer wings. Bosch’s lesson, if there is one, seems to be that we can choose good over evil or we can be swept away. Man proposes, God disposes.

Hieronymus Bosch, Last Judgment Triptych

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Hieronymus Bosch, Last Judgment Triptych, 1504-08, overall dimensions 163 x 250 cm, central panel 163 x 128 cm, wings 163 x 60 cm (Akademie für bildenden Künste, Vienna)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Gerard David, The Virgin and Child with Saints and Donor

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Gerard David, The Virgin and Child with Saints and Donor, c. 1510, oil on oak, 105.80 x 144.40 cm (The National Gallery, London)

Jan Gossaert, Saint Luke Painting the Madonna

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Dutch Proverbs

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Dutch Proverbs, 1559, oil on oak, 117 x 163 cm (Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Tower of Babel

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Tower of Babel, 1563, oil on panel, 114 × 155 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

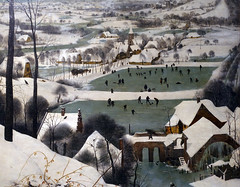

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Hunters in the Snow (Winter)

Video \(\PageIndex{6}\): Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Hunters in the Snow (Winter), 1565, oil on wood, 118 x 161 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

Pieter Bruegel’s Hunters in the Snow offers a bird’s eye view of a world locked in winter that is nevertheless teeming with life, with hunters and their dogs and ice skating peasants and a wheeling crow and the busied preparations for the cold weather.

The painting, usually interpreted as a genre scene (an image of daily life), features a snow-covered landscape that recedes dramatically to a row of jagged mountains in the distance, all under a blue-grey sky. In the lower left corner a trio of hunters and their pack of dogs return from a hunt. Beside them is an inn, and its rust-colored bricks and the bright yellow fire in front of it are a striking contrast to the whites and grays and ashy blues that dominate the painting.

The branches of three large trees in the foreground fan out like black capillaries against the sky and a few crows keep watch over the scene. From the left side of the painting the land slopes down and to the right, and beyond the foreground the landscape drops away sharply. The extensive middle ground and background, rendered in minute detail, depicts the natural and manmade world: a person carrying a load of sticks over a bridge, figures ice skating on a frozen pond, the snow-covered roofs of houses, innumerable tiny bare trees, and—far in the distance on the right side—the grey and snowy mountains, whose rough peaks seem to scratch at the sky. The right side of the painting is thus an uninterrupted view across the snowy valley. We see everything so clearly—even way into the distance it’s possible to make out individual trees and rooftops—and so we sense the crisp and clear air of a winter day. Yet this is not at all an image from reality: there is no such landscape in the Netherlands (which is mostly flat and below sea level in some areas). Rather, Bruegel combined images from his surroundings—the inns and farmhouses and frozen ponds of Northern Europe—with a chain of jagged mountains reminiscent of the Alps, which he saw on a journey to Italy in the 1550s. The painting is thus a carefully constructed scene, drawn as much from the artist’s imagination as from his surroundings.

Close looking: searching for the details

Bruegel’s paintings reward close viewing, and in some instances—like his Fall of Icarus, in which the figure of Icarus is nearly hidden in the background—careful looking is the only way to fully appreciate the complexity of the scene. This painting offers similar rewards: the longer and more attentively we examine the details the more we can draw from this image of a winter day.

The hunters and their dogs are the largest figures in the painting and their group takes up much of the lower left quarter of the image. But rather than a scene of triumph, Bruegel is showing us a rather unsuccessful hunt. The men trudge through the snow wearily; note, for example, how the figure closest to us leans forward slightly, as though using his own body to keep his momentum—and his spirits—going. Each man also has his head cast downward, in a pose reminiscent of defeat. Even the dogs appear downtrodden, as several in the extreme lower left hang their heads—a point exaggerated by their drooping ears.

The group’s low spirits can be explained by the fact that only one of them carries back a trophy: a rather small fox. Furthermore, a trail of rabbit tracks in front of the foremost hunter suggests that more prey have recently escaped them.

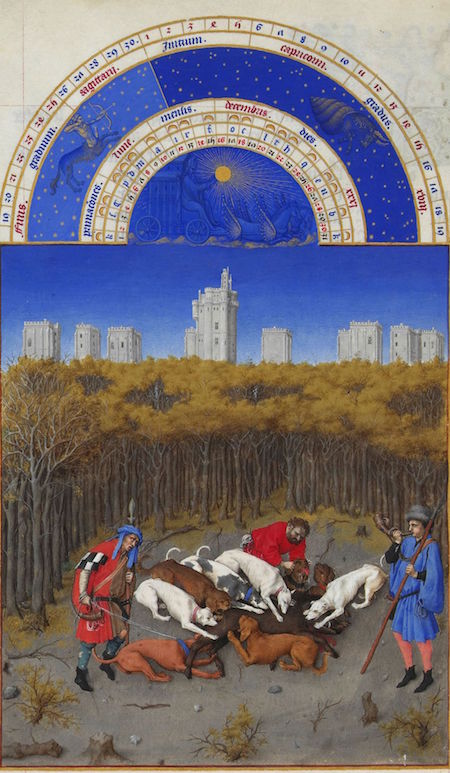

Hunting rights and specially-bred hunting dogs were often associated with the aristocracy in the Northern Renaissance, and we see examples of such imagery in works like the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (left), a prayer book painted by the Limbourg Brothers for the Duke of Berry, the brother of the King of France.

Yet in Bruegel’s painting, the identity of the hunters is not so clear, as the rest of the painting’s inhabitants are peasants, most of whom seem to be enjoying the winter day. The figures in front of the inn are preparing a fire for the singeing of a pig—a traditional December activity—and in the distance people take pleasure in the frozen lake: ice skating, playing hockey or a form of curling, and pulling companions on sleds.

There is thus a certain idyllic quality to Bruegel’s portrayal of peasant life, and it may be that the hunters—whose bodies point us to the center of the painting—are more a means of guiding us into the painting rather than its primary focus (despite the title art historians have given the work).

The painting’s commission and sources

Bruegel’s painting, with its bare trees and people bundled against the cold and hard-packed snow, is part of a long tradition in Northern European art of portraying the months of the year and the activities that occurred during each month. Among the most famous examples is the cycle found in the previously mentioned Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (above). In that manuscript’s small but incredibly detailed paintings, each month is represented in a full-page miniature with an outdoor landscape scene (except January, which shows an indoor feasting scene) and either a courtly or peasant activity, such as hunting one month and working the land in another.

In Bruegel’s case the paintings were commissioned by a wealthy Antwerp banker named Niclaes Jongelinck. Rather than twelve paintings, Bruegel’s cycle divided the year into six seasons (paintings for five survive—the other four are The Harvesters, Return of the Herd, The Gloomy Day, and Haymaking). He has also chosen to give as much or more emphasis to the landscapes than to the activities depicted, with particular attention paid to the shifting colors of the times of year, from dark brown to blues and greens to yellows. This image—of winter—is the last in the series, dominated by whites and pale blues. If we imagine how they might have been displayed together in a room in Jongelinck’s house the effect would have been a chromatic progression through the seasons.

Bruegel: the artist and his enduring fame

Bruegel’s focus on peasant activities in this cycle is something we might expect from him, as he is best known for his intimate, sensitive, and sometimes comical scenes of peasant life. Yet he was also a well-traveled and worldly artist who could craft complex scenes out of seemingly mundane activities. The painting’s distant mountains (below), drawn from his travels south of the Alps and so clearly a construction of the artist’s mind, are key to understanding how Bruegel has constructed the entire painting.

What appears to be a candid snapshot of daily life—a cold and overcast winter day—is in fact a finely orchestrated and panoramic vision of the world. The sloping diagonals on the left—the roofs and the ground—lead our eyes into the scene, and their rhythm is countered by a series of horizontal elements—bridges and land—and the diagonals of hills and mountains on the right.

The high horizon line suggests that we, the viewer, experience this scene from high above, the same perspective as might be enjoyed by the crows in the foreground trees’ branches. This type of complex view—which combines an interest in human activity with the expansive and commanding vista of a map—defines much of Bruegel’s work. His masterful ability to blend sweeping vistas with intimate portrayals of the human condition, and the mundane with the fantastical, is part of what makes his paintings—including Hunters in the Snow—so enduring. In replicating the world on a scale both large and small he seems to present a mirror to the human condition itself: continuously locked to life’s day to day activities, yet often striving to see the world in all its glory in an instant.

The five extant paintings by Pieter Bruegel the Elder in this series include:

Hunters in the Snow (Winter), 1565 (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

The Gloomy Day, 1565 (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

Haymaking, 1565 (National Museum, Lobkowicz Palace, Prague)

The Harvesters, 1565 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

The Return of the Herd, 1565 (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

Additional resources:

This painting at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

This painting at the Google Cultural Institute

Pieter Bruegel the Elder on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn TImeline of Art History

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Peasant Wedding

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{7}\): Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Peasant Wedding, oil on canvas, 114 x 164 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

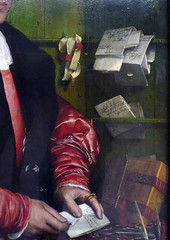

Pieter Aertsen, Meat Stall

by DR. IRENE SCHAUDIES

Even if you are not a vegetarian, this painting is bound to come as something of a shock. Anyone accustomed to purchasing meat in the clean, cold corridors of the supermarket—safely wrapped in plastic and utterly divorced from the living animal it once was—may feel the urge to shrink back from the vivid, frontal display of so much raw flesh, much of it with eyes, ears, mouths and tongues still attached.

The partially skinned ox head, in particular, seems to eye the viewer balefully, as if he or she were responsible for its death. You can almost hear the flies buzzing in the air…

Even more surprising, if you look in the background on the left, is a small scene depicting the Flight into Egypt (when Joseph, Mary and the infant Jesus flee to Egypt because they learn that King Herod intends to kill the male infants in the area of Bethlehem). We see the Virgin Mary on her donkey reaching back to offer bread to a young beggar. Saint Joseph follows closely at her side. This charitable scene stands in stark contrast to the bloody abundance of meat in the foreground.

If we look closely though, in the right background, we see tavern scene that is more in keeping with this feeling of excess in the foreground. Here we see people eating mussels by a snug fire. A great carcass hangs in the same room, and a butcher (we recognize him as such thanks to his red coat, which in Antwerp could only be worn by guild members) appears to be adding water to the wine for his guests. But why would an artist depict meat at all, let alone in such an unsavory way and in combination with a religious scene?

The way of the flesh and the way of the spirit

The Dutch painter Pieter Aertsen, who worked for many years in Antwerp, was later renowned for his life-size market scenes with exuberant still life elements. Many scholars have commented on the bold originality of Aertsen’s compositions, and rightly so. In the sixteenth century, religious or mythological scenes usually occupied pride of place in works of art, while everyday objects were considered mere accessories. In this and other roughly contemporary works like Christ in the House of Mary and Martha (below), Aertsen has deliberately reversed this formula. He gave all the attention to the accessories, which seem to spill out of the picture and into the viewer’s own space.

Aertsen certainly seems to have been the first to foreground meat in a prestigious, costly oil painting on a monumental size. However, he may also have been inspired to upend traditional hierarchies of subject matter (giving most of the attention to the still-life elements) by the painter and printmaker Lucas van Leyden’s Ecce homo scene (Ecce homo means “behold the man” and refers to Pontius Pilate presenting the beaten Christ crowned with thorns before his crucifixion). Leyden, in Christ Presented the People (below), shows a great market square with a crowd in the foreground, while Christ himself has been relegated to the background.

This may be a comment on the arduous nature of spirituality: those who truly seek enlightenment must look hard, and turn their attention away from the things of this world. And indeed, in Aertsen’s picture, the crossed herring on a pewter plate just above the ox’s head—fish was associated with Lent, a period when the faithful abstained from meat—seem to point in the direction of the holy scene in the background, beyond the meat.

Other scholars have suggested that Aertsen’s inversion of traditional hierarchies was inspired by sources from classical antiquity—though perhaps equally moralizing. The Roman satirist Juvenal, for example, chastised the lovers of lavish meals in his eleventh satire, lambasting their fondness for “stinking meat shops” instead of plain, wholesome food. Closer to Aertsen’s own time, the philosopher Desiderius Erasmus used irony to make a point: undesirable behavior is heaped with praise to throw its negative aspects into sharp relief, while the reader is treated to a good laugh. Erasmus does this to great effect in In Praise of Folly (1511), a book that Aertsen and his contemporaries may very well have read.

The art of rendering well

Aertsen’s bold move can also be seen in light of his artistic context. Antwerp in the mid-sixteenth century was one of the greatest centers of mercantile trade at the time: populous, prosperous, and booming. It was the second largest city in northern Europe—smaller than Paris but bigger than London—and arguably also the wealthiest. Merchants came from around the world to deal in spices, staple goods, finance, and especially luxury goods like glass, fine textiles, precious furnishings, and works of art. The number of artists attracted to this concentration of wealth was considerable, and this in turn encouraged specialization, a situation that may also have encouraged Aertsen to flaunt his skill in painting lifelike elements such as fruit, vegetables, cheese, and meat in the market scenes for which he is now famous (see the image above).

Like so many other specialties we take for granted today: landscapes, flower pieces, scenes from everyday life, etc. market scenes were just beginning to emerge as subjects in their own right, independent of paintings that depicted mythological or religious scenes—which, by the way, Aertsen also painted in considerable numbers (see below), though not all of them survived the waves of iconoclasm (the destruction of images) that swept across northern Europe in the wake of the Protestant Reformation.

Topical concerns

Aertsen’s originality and painterly skill would have been sufficient to charm an international connoisseur among Antwerp’s wealthy merchant community, who came from countries as diverse as Spain, Portugal, Sweden, Poland, Germany, and of course Italy.

But for those familiar with Antwerp’s tangled local politics, there are some highly specific messages embedded in this composition that would have been legible only to them. In the upper left-hand corner is a small representation of two hands—the symbol of the city of Antwerp—and chalked on the post next to it are symbols typical of guild marks belonging to specific individuals, though their identity remains a mystery.

The Butchers’ Guild in Antwerp was a very powerful institution that enjoyed the support of Emperor Charles V himself. It was one of the few guilds with a written charter, and succeeded in having its profession closed to outsiders: there could only be sixty-two officially recognized butchers in the city at any given time, and when a butcher passed away his post would go to his son or other close male relative. Anyone who wanted to buy meat in Antwerp had to buy it from the Vleeshuis, or “Meat Hall,” an imposing building near the banks of the River Scheldt that was rivaled as a landmark only by the Church of Our Lady (now the cathedral of Antwerp), truly a sign of the guild’s power. Nevertheless, the butchers’ influence was coming under increasing attack in 1551: butchers from outside the city had banded together to fight what they perceived as an unfair trade monopoly. They filed a lawsuit that was first overturned, then upheld, then appealed by the Butchers’ Guild in the imperial courts—and the results were still pending when Aertsen painted his striking panel. Meat was a hot item indeed!

But there is more. At the upper right, posted on top of the meat stall, is a small sign in Dutch that, when translated, reads: “Land for sale out back: 154 rods, either by the piece or all at once.” This text refers to an actual sale of land that took place in 1551, and a controversial one at that. It must have been important to the picture’s original meaning, because the sign appears in all four, almost identical versions of the Meat Stall that Aertsen painted. To make a long story short, the city of Antwerp decided to develop what was then the southeast side of town. Land being in short supply, the city council forced the prestigious order of Augustinian nuns who ran the St. Elisabeth’s hospital to sell their property at a loss. But the city bought too much acreage, so the surplus was sold to one Gillis van Schoonbeke, a notorious real estate developer whose activities were so unpopular that they even caused riots. At one point imperial troops had to be called in to stop the violence.

Given this background, the painting with its layered messages—all of which warn against greed and excess—must have seemed emblematic of the rapid social changes overtaking the city, which experienced unprecedented growth thanks to its booming international trade. Traditional groups and values, such as the charitable nuns and their inviolable property, or the venerable butchers and their hereditary rights, were under fire from powerful, wealthy entrepreneurs and the city’s desire for economic growth, a matter of concern for all citizens.

Additional resources:

Works by Aertsen on the Google Art Project

Kenneth M. Craig, “Pars Ergo Marthae Transit: Pieter Aertsen’s ‘Inverted’ Paintings of ‘Christ in the House of Martha and Mary,’” Oud Holland, vol. 97 (1983), pp. 25–39.

Elizabeth Alice Honig, Painting and the Market in Early Modern Antwerp (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998).

Charlotte Houghton, “This Was Tomorrow: Pieter Aertsen’s Meat Stall as Contemporary Art,” The Art Bulletin, vol. 86 (June 2004), pp. 278–300.

Ethan Matt Kavaler, “Pieter Aertsen’s Meat Stall: Divers Aspects of the Market Piece.” Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek, volume 40. 1989, pp. 67–92.

Keith Moxey, “Interpreting Pieter Aertsen: The Problem of ‘Hidden Symbolism,” Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek, vol. 40 (1989), pp. 29–40.

Keith Moxey, Pieter Aertsen, Joachim Beuckelaer and the Rise of Secular Painting in the Context of the Reformation (New York: Garland, 1977).

Margaret A. Sullivan, “Bruegel the Elder, Aertsen, and the Beginnings of Genre,” The Art Bulletin, vol. 93 (June 2011), pp. 127–49.

Bernard van Orley and Pieter de Pannemaker, The Last Supper

by THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART

Video \(\PageIndex{8}\): Bernard van Orley and Pieter de Pannemaker, The Last Supper, ca. 1524–46 (design), ca. 1525–28 (woven), wool, silk, silver-gilt thread, 131 7/8 x 137 13/16″ / 335 x 350 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). Video from The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Additional resources:

Germany and England

Cranach, Dürer, and Holbein—and all other artists after 1517—lived in a world forever changed by the Protestant Reformation.

1500 - 1600

Albrecht Dürer

Who was Albrecht Dürer?

by MINNEAPOLIS INSTITUTE OF ART

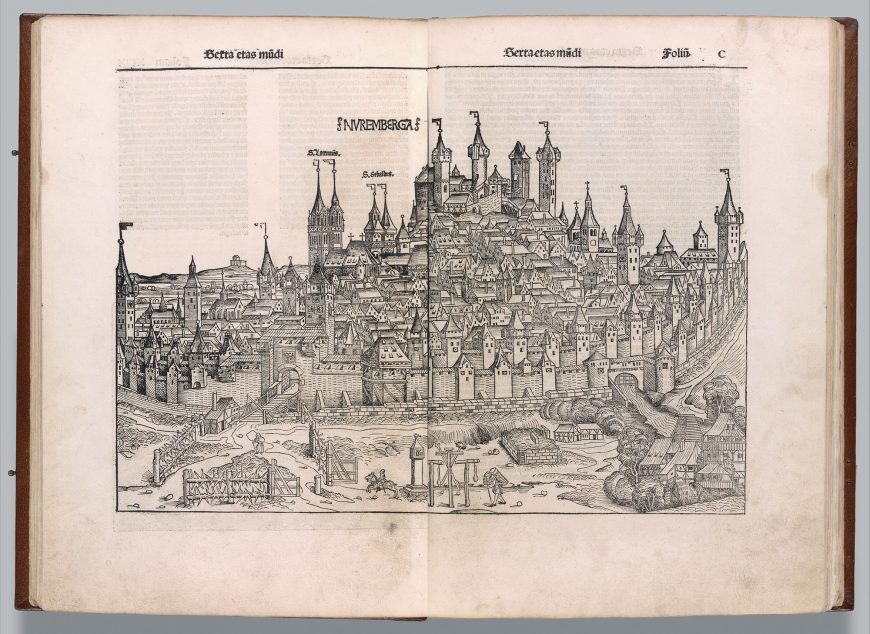

Albrecht Dürer was born in Nuremberg on May 21, 1471. His father, a talented goldsmith, taught him the basics of drawing and metalworking, including the skill of engraving. The boy’s aptitude led to his being apprenticed from 1486 to 1489 to Nuremberg’s leading painter, Michael Wolgemut.

In addition to being a painter, Wolgemut was a prolific designer of woodcut prints, primarily used for book illustrations. His principal client was Anton Koberger, one of the leading publishers in Europe, as well as Dürer’s godfather.

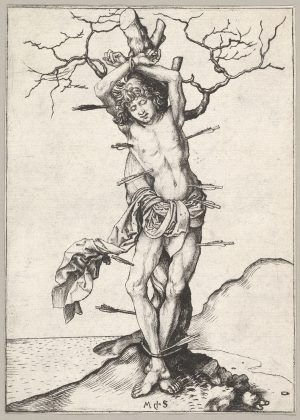

Following his apprenticeship, Dürer set out as a journeyman, traveling to great art centers in Germany and the Netherlands. His tour lasted four years. He had hoped to go to Colmar to meet Martin Schongauer, a famous painter and the leading engraver in Germany, but by the time Dürer arrived in Colmar, Schongauer had died. Fortunately, Schongauer’s brothers gave Dürer access to the prints and drawings in his studio. Dürer went on to work with another of the brothers, a goldsmith in Basel.

Dürer returned to Nuremberg in 1494. Within six months he had married and set off again, this time for Italy. During a sojourn of several months, he came into direct contact with the art and artists of the burgeoning Italian Renaissance. His studies of the works of Antonio Pollaiuolo, Andrea Mantegna, Giovanni Bellini, and others brought changes to his own art. He began to combine the structure and corporeality of Italian art with the profuse detail and emotive narration of northern European art.

During the later 1490s his most remarkable project was an illustrated edition of The Apocalypse of Saint John, the Bible’s Book of Revelations. The book, with its visionary, full-page woodcut prints, made Dürer one of the most famous men in Europe.

At the same time, Dürer perfected his skills in other disciplines, including both oil and watercolor painting, drawing, and above all, engraving. By his 30th birthday, Dürer was an engraver without peer, and remains so today. His studies of nature, proportion, and perspective, reaching their apogee in his studies of human anatomy, laid the foundation for brilliant engravings such as Adam and Eve, his self-conscious masterpiece of 1504.

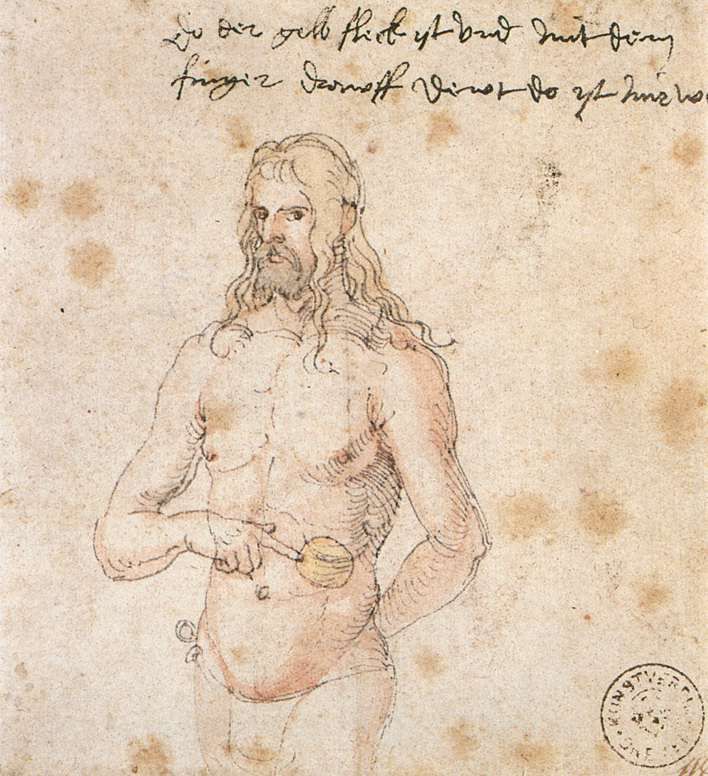

Dürer traveled to Italy again from 1505 to 1507, possibly in an attempt to shut down copyists who were stealing his ideas. His renewed contact with Italian artists deepened his fascination with art theory, and he soon began intensive studies that would lead to the publication of detailed treatises on human proportion, applied geometry, and military fortification. Though the geometry treatise would not appear until 1525, he was working on it in the early 1510s, while also studying nature and preparing Melencolia I. The wings of the angel in Melencolia I bring to mind his famous watercolor of a bird’s wing (below), which he drew in 1512. Melencolia I is sometimes called Dürer’s “summa” because it brings together so many of his interests and ideas.

Dürer’s patrons included the uppermost reaches of society, including Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, who awarded Dürer’s annual pension. Yet Dürer avoided becoming exclusively a court artist, preferring entrepreneurship. He continued to paint, but he clearly realized that the printing press was a more reliable source of income. As early as 1508, he wrote to a patron, “I shall stick to my engraving, and if I had done so before I should today be a richer man by 1,000 florins.” Dürer employed agents, including his wife, Agnes, to sell his prints, thus freeing him to work on time-consuming projects.

In July 1520, not long after the death of the emperor, Dürer departed for a year-long trip to the Netherlands. He hoped to persuade the new Emperor Charles V to renew his pension. Along the way he basked in the great celebrity accorded him in city after city. He met other great artists, royals, and intellectuals. His diary from this trip reveals that he often gave prints, occasionally including Melancolj (as he called it) as gifts.

After his return to Nuremberg, Dürer complained of his failing eyesight and stiffening hands. In later years, his productivity as an engraver slowed, but he continued to publish his prints. His earlier engravings have been found printed on papers from the 1520s. He died in 1528, leaving Agnes an estate of 6,874 florins, more than ten times the annual salary of the mayor of Nuremberg. The reprinting of Dürer’s engraved plates and woodblocks continued for centuries, though they became increasingly incapable of producing such beautiful impressions as the one on display here.

Additional resources:

Works by Albrecht Dürer at the Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia)

Essay on Albrecht Dürer from The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Essay on Albrecht Dürer from the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

“The Strange World of Albrecht Dürer” from the Clark Institute

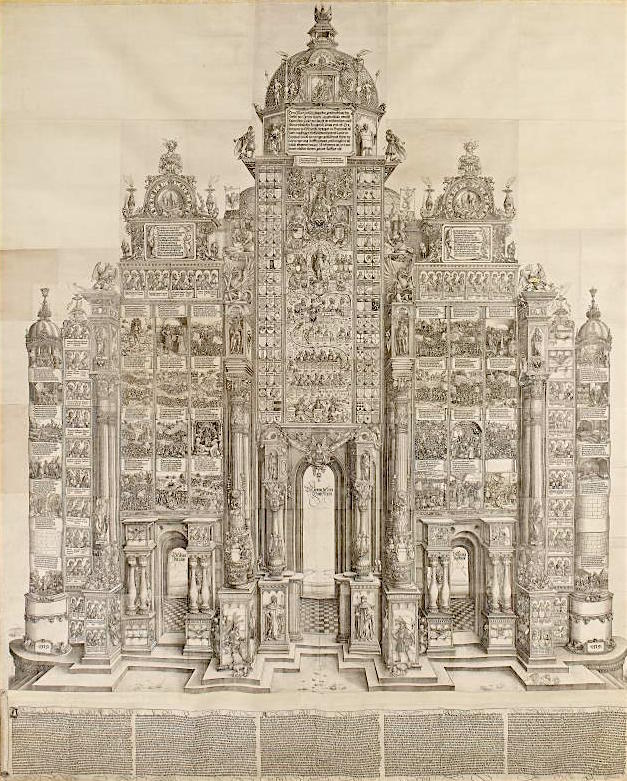

Albrecht Dürer, The Triumphal Arch

The Triumphal Arch is one of the largest prints ever produced. It was commissioned by the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I (1459-1519). The program was devised by the court historian and mathematician, Johann Stabius, who explains underneath that it was constructed after the model of “the ancient triumphal arches of the Roman Emperors.”

Above the central arch, entitled “Honor and Might,” is a genealogy of Maximilian in the form of a family tree (above). Above the left arch, “Praise,” and the right arch, “Nobility,” are represented events from his life. These are flanked by busts of emperors and kings on the left (image, left), and a column of Maximilian’s ancestors on the right. The outermost towers on either side show scenes from the private life of Maximilian.

The architect and painter Jörg Kölderer designed the overall appearance of the structure, and Dürer designed the individual scenes and architectural elements, some of which he sub-contracted to his pupils Hans Springinklee and Wolf Traut, and Albrecht Altdorfer of Regensburg.

The date 1515, which appears on the Arch, refers to the completion of the designs; the blocks were cut by Hieronymus Andreae of Nuremberg between 1515 and 1517. This impression belongs to the first edition of 1517-18 when about seven hundred sets were printed, but they are today very rare. It is undecorated apart from the word Halt in the German Halt Mass (“Keep to moderation”) which is gilded.

Additional resources:

View details on the British Museum website

G. Bartrum (ed.), Albrecht Dürer and his legacy (London and N.J., The British Museum Press and Princeton University Press, 2002).

E. Panofsky, The life and art of Albrecht Dürer (Princeton University Press, 1945, 1971).

G. Bartrum, German Renaissance prints (London, The British Museum Press, 1995).

© Trustees of the British Museum

Albrecht Dürer, Self-portrait, Study of a Hand and a Pillow (recto); Six Studies of Pillows (verso)

by THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART

Video \(\PageIndex{9}\): Albrecht Dürer, Self-portrait, Study of a Hand and a Pillow (recto); Six Studies of Pillows (verso), 1493, pen and brown ink, 10 15/16 x 7 15/16″ / 27.8 x 20.2 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art). Video from The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Albrecht Dürer, Self-Portrait (1498)

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{10}\): Albrecht Dürer, Self-Portrait, 1498, oil on panel, 52 x 41 cm (Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid)

Albrecht Dürer, Self-Portrait (1500)

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{11}\): Albrecht Dürer, Self-portrait, 1500, 67.1 x 48.9cm (Alte Pinakothek, Munich)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Albrecht Dürer, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse

Cowboy movies

Albrecht Dürer’s woodcut, Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, always reminds me of my lifelong love of Hollywood cowboy movies. American westerns are almost all predicated on Christian themes, and riddled with simple symbolic numbers. Maybe you are familiar with the 1960 Western The Magnificent Seven and their connection to the Seven Virtues? And in terms of the Seven Vices, in the 2007 remake of 3.10 to Yuma, the ‘villain,’ Ben Wade, is trailed by six members of his outfit who try to free him from his captors—his release would restore their numbers to seven (and need I point out that ten minus three—the 3.10 of the title— is seven?). In the original poster for High Noon, Gary Cooper confronts four villains. This is why, for me, Durer’s Four Horsemen, drawn from the Book of Revelation (the last book of the New Testament which tells of the end of the world and the coming of the kingdom of God), have always been the sinister apocalyptic cowboys of world-ending destruction; Conquest, War, Pestilence (or Famine) and Death itself.

Of course, that’s not at all what Dürer intended. The image was made as one of a series of fifteen illustrations for a 1498 edition of the Apocalypse, a subject of popular interest at the brink of any new millennium. In 1511, after the world had failed to end, the plates were republished and further cemented Dürer’s enduring fame as a print-maker.

The horsemen

In the text of Revelation, the main distinguishing feature of the four horses is their color; white for conquest, red for war, black for pestilence and/or famine, and pale (from ‘pallor’) for death (Clint Eastwood, Pale Rider, anyone?). The riders each arrive armed with a rather obvious attribute; conquest with a bow, war with a sword, and a set of balances for pestilence/famine. Dürer’s pale rider carries a sort of pitchfork or trident, despite the fact that he’s given no weapon in the Biblical account; he simply unleashes hell.

Here’s the text from Revelation, chapter 6:

The First Seal—Rider on White Horse

Then I saw when the Lamb broke one of the seven seals, and I heard one of the four living creatures saying as with a voice of thunder, “Come.” I looked, and behold, a white horse, and he who sat on it had a bow; and a crown was given to him, and he went out conquering and to conquer.The Second Seal—War

When He broke the second seal, I heard the second living creature saying, “Come.” And another, a red horse, went out; and to him who sat on it, it was granted to take peace from the earth, and that men would slay one another; and a great sword was given to him.The Third Seal—Famine

When He broke the third seal, I heard the third living creature saying, “Come.” I looked, and behold, a black horse; and he who sat on it had a pair of scales in his hand…”The Fourth Seal—Death

When the Lamb broke the fourth seal, I heard the voice of the fourth living creature saying, “Come.” I looked, and behold, an ashen horse; and he who sat on it had the name Death; and Hades was following with him. Authority was given to them over a fourth of the earth, to kill with sword and with famine and with pestilence and by the wild beasts of the earth.

The quality of Dürer’s woodcut is breathtaking; one hears and feels the furor of the clattering hooves and the details, shading and purity of form are astonishing. Dürer’s unique genius as a woodcut artist was his ability to conceive such complex and finely detailed images in the negative—woodcut is a relief process in which one must cut away the substance of the design to preserve the outlines. Before Dürer it was often a rather crude affair. No one could draw woodblocks with the finesse of Dürer (much of the cutting was done by skilled craftsmen following Dürer’s complex outlines). The images are astonishingly detailed and textural, as finely tuned as drawings. So influential was Dürer’s graphic output, in both woodcut and engraving, that his prints became popular models for succeeding generations of painters. He was no mean painter himself, producing a varied and articulate array of self-portraits, as well as religious works, and turning his mind and his hand to the production of an influential book on perspective. He was a humanist, painter, print-maker, theorist and keen observer of nature and is therefore often referred to in popular discourse as the ‘Leonardo of the North’—although his actual output was considerably greater than that Italian Renaissance master.

Dürer’s particular genius here is the translation of the distinctive colors of the horses into a black-and-white medium, which he achieves by very distinctly drawing their various weapons and by placing them in order from background to foreground, slightly overlapping, so that they ride across the composition in the same order as they appear in the text. This places the apparition of Death, a skeletal monster on a skeletal horse, in the foreground, trampling the figures in his path.

In the wake of Death’s trampling hooves, a monstrous, fanged reptilian creature noshes on the mitre of a Bishop, a prefiguration, perhaps, of the imminence of the Protestant Reformation that would sweep across northern Europe in opposition to the excesses of the church and papacy.

In this context, the thundering hooves of the horses could presage religious reform (Dürer’s Four Apostles, painted for Nuremberg’s town hall, bears inscriptions from the texts of Martin Luther), although Luther himself did not approve of the visionary nature of Revelation, declaring it, “neither apostolic nor prophetic.”

Albrecht Dürer, The Large Piece of Turf

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{12}\): Albrecht Dürer, The Large Piece of Turf, 1503, watercolor and gouache on paper, 16-1/8 x 12-5/8 inches (41 x 32 cm) (Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna)

Albrecht Dürer, Adam and Eve

Is there anything left to say about Adam and Eve, quite literally the oldest story in the book? The engraving of Adam and Eve of 1504 by the German renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer recasts this familiar story with nuances of meaning and artistic innovation. In the picture, Adam and Eve stand together in a dense, dark forest. Far from the garden evoked in Genesis, this forest is distinctly German, the dark woods of the devils and spooks of Grimm’s fairy tales. Foreign and unexpected motifs intrude into this German wood.

The figures

Despite the chill of the forest, the two human figures appear nude. Their bodies are frontal, and they stand in a classical contrapposto, or counterpoise, where the weight of the body is shifted onto one foot. The corresponding shift in hips and shoulders creating a convincing illusion of a body capable of movement but temporarily at rest. Despite this apparent naturalism, their heads are turned to the side as they gaze at one another. This twisting configuration of head and body is distinctly artificial. The naturalizing contrapposto clashing with the artificiality of the rest of the pose establishes a pattern of contradictions that run throughout the picture. A seemingly astutely observed tree becomes distinctly odd, as we recognize that Eve is plucking an apple from a tree with fig leaves. A parrot, a tropical bird, perches on a branch to the viewer’s left. Six other animals stroll disinterestedly through or stand about—an elk, ox, cat, rabbit, mouse, and goat.

The cartelino or small sign hanging from branch Adam grasps contains its own contradiction. It proudly identifies the artist as a citizen of the Franconian city of Nuremberg (Noricus), but does so in Latin, the language of the Mediterranean, of the Roman Empire and of the Italian Renaissance. How does this curious blend of motifs further the story of Adam and Eve?

A departure from Genesis

The answer is that the picture tells us primarily about the Renaissance, about Germany, and about Dürer himself rather than the text of Genesis, from which it departs most strikingly. The poses of the two human figures are contrived to show off this German artist’s knowledge of classical (Greco-Roman) proportions. Based on the ideals of the Roman architect Vitruvius, the proportions of the face—for instance the distance from forehead to chin—determine the ideal proportions of the rest of the body. Dürer sacrifices naturalism to showcase his mastery of Vitruvian ideals.

Symbols

Colorful, tropical parrots were collectors items in Germany, and they were also symbols in art. The call of the parrot was believed to sound like “Eva-Ave” —Eve and Ave Maria (“Hail Mary”—the name of a prayer in honor of the Virgin Mary). This word play underpins the Christian interpretation of the story of the Fall of Humanity by characterizing the Virgin Mary, mother of Christ, as the antidote for Eve’s sin in the Garden of Eden. The other animals bear other symbolic meanings. The elk, ox, rabbit, and cat exemplify the four humors or human personality types, all of which correlate with specific fluids in the body.

- Melancholic: elk, black bile

- Phlegmatic: ox, phlegm

- Sanguine: rabbit, blood

- Choleric: cat, yellow bile

Only Adam and Eve are in perfect balance internally. After the Fall, one humor predominates in everyone, throwing our temperaments into imbalance. Dürer’s placid animals signify that in this moment of perfection in the garden, the human figures are still in a state of equilibrium. The cat does not yet chase the mouse, and the goat (a reference to the scapegoat of the bible) is still standing on his mountain perch.

A German enthralled by the classical tradition

The print allows Dürer to express his personal and cultural concerns. Proud of his German identity (Albert Dvrer Noricvs or “Albert Dürer of Nuremberg”), the artist is nonetheless enthralled by Italian and classical tradition. The German forest is ennobled by classically proportioned figures who actually reference Greek sculptures of Venus and Apollo, and anchored in tradition with the symbolism of the humors. In Renaissance fashion, the perfect physical proportions of the body correlate with the interior harmony of the humors.

Mechanical reproduction

The advent of mechanically reproducible media, both woodcuts and intaglio prints, was a revelation for Dürer and his entire world. Into a world where each image was handmade, one of a kind, and destined for one location, mechanical reproducibility offered something entirely different. Pictures made in multiples, such as the Adam and Eve engraving, meant that the ideas and designs of a German artist could be known in other regions and countries by large numbers of people. German artists could learn about classical art without traveling to Italy. More kinds of people could afford more pictures, because prints are easier to produce and typically less expensive than paintings. The traditional, direct contract between artist and patron, where one object was hand-produced for one patron and one place, gave way to a situation where multiple images could be seen by unknown viewers under an infinite variety of circumstances.

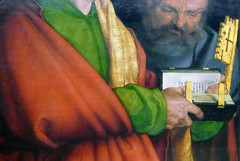

A scientific mind