3.2: Theatre History, in Brief!

- Page ID

- 187850

Theatre is loosely defined as an intentional performance by one person in front of an audience. The beginnings of theatre are unknown. There are several theories, including the Ritualist theory, suggesting theatre began with religious rituals which became codified and performative. The Great Man theory offers that one person’s genius can be attributed to the origin of the art form. The Storytelling theory posits that theatre evolved as a way to enhance storytelling through impersonation. There is no evidence to prove any of these, or several other theories, as the true and correct origin point for theatre; however, the Ritualist theory is the most often accepted, although some questionable research methods were employed.

The Ancient Greeks

The Greek philosopher, Aristotle, (384 BCE – 322 BCE) stated that mimesis (imitation), is inherent in all humans, and both he and Plato refer to it as the “re-presentation of nature.”

Early Greek theatre developed through song and poetry and grew into the well-known forms of tragedy and comedy we now associate with it. Dithyrambs, passionate hymns sung and danced to honor Dionysus, the god of wine and fertility, were performed by a chorus of men and boys as part of Dionysian festivals. The City Dionysia, or Great Dionysia, was held in Athens in the Spring. The festival had dramatic competitions in which three tragic poets would write, produce, and perform in three tragedies, as well as a satyr play (a vulgar comedy mocking some heroic subject). Later, when comedy was added, five comic poets would each enter one play. The judges would be picked by lottery, and the winning poet awarded a prize.

Dithyrambs were the basis for tragedy, but how did the switch from dithyrambic verse to tragedy occur? This is where the Great Man origin theory makes sense. According to legend, Thespis, a tragic poet, was the first person to step out of the dithyrambic chorus of fifty men and add character speeches and dialogue between the actor (protagonist) and the leader of the chorus (choragus) during a performance. This synthesis of existing dramatic elements and the addition of characterization became the birth of tragedy.

Aristotle broke tragedy down into six parts: Plot, Character, Diction, Thought, Spectacle, and Song. “Tragedy, then, is an imitation of an action that is serious, complete, and of a certain magnitude; in language embellished with each kind of artistic ornament, the several kinds being found in separate parts of the play; in the form of action, not of narrative; through pity and fear affecting the proper purgation of these emotions.”

There were many tragic poets (playwrights) who presented works at the Dionysian festivals over the years. Unfortunately, for any number of reasons, very few of their plays remain. The three best-known ancient Greek tragedians are Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides.

Aeschylus (525 BCE – 456 BCE) was a poet who may have written between eight to ninety plays, of which we only have seven complete texts and several fragments. Aeschylus is credited with diminishing the size of the chorus from fifty to twelve men and adding a second actor (deuteragonist). His best-known work is the dramatic trilogy, the Oresteia, which portrays the story of the House of Atreus. The trilogy is composed of Agamemnon, The Libation Bearers, and The Eumenides. The only complete trilogy of Greek drama to survive, the Oresteia was first performed in 458 BCE.

Sophocles (496 BCE – 406 BCE) was the younger contemporary of Aeschylus. He wrote prolifically, possibly as few as ninety or as many as one hundred and twenty-three plays, of which seven remain. He is said to have competed in the City Dionysia approximately thirty times and won twenty-four times. His best-known plays are Oedipus Rex and Antigone. Aside from the sheer volume of work he produced, Sophocles is known for his dramatic innovations. He changed the number of chorus members from twelve to fifteen and added the third actor (tritagonist). This allowed for more characters onstage, as well as more complex plots and interactions.

The third of the great tragedians was Euripedes (485 BCE – 406 BCE). His works differed from his predecessors by focusing on the more human aspects of heroes, as well as their fallibility. His characters also included strong female protagonists, as seen in Medea and Trojan Women. Euripedes also diminished the importance of the chorus. In Medea, which is practically a domestic drama, focusing on an individual character’s personal tragedy, the chorus is more of a hindrance to the story than a help.

As these playwrights developed tragedy, Aristophanes (448 BCE – 388 BCE) blended comic elements from folk traditions, as well as politics of the day to create Greek comedy. Plays written before 400 BCE are called Old Comedy, and Aristophanes’ plays fall into this category. There were many Old Comedy playwrights, but only eleven texts survive, all of them by Aristophanes. His plays focused on satirical social and political commentary. In Lysistrata, his most popular comedy, the women of Athens go on a sex strike to end a war.

Between approximately 350 BCE through 250 BCE was the period when New Comedy was preferred. Menander (342 BCE – 292 BCE) wrote in this new style and although we have no complete plays of his, there are enough fragments to note its difference from the Old Comedy. Menander’s plays deal with situations of urban life rather than political satire. The plays are more like a comedy of manners than the religious plays of theatre’s origins. The smart and cunning slave has a main role in Menander’s writing.

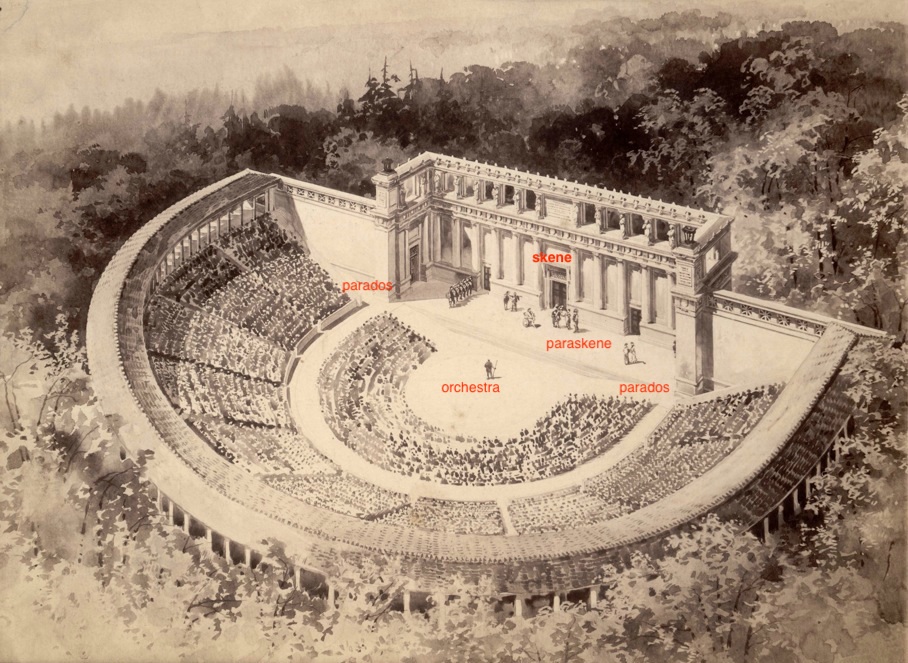

Greek drama was performed in outdoor theatres built into the hillside. The Theatre of Dionysus had a slope called the theatron (seeing place) and the flat area below was the orchestra (dancing place). There was an altar to Dionysus set in the middle of the orchestra. Later, a permanent structure was built that included stone seating in a semi-circle, a circular orchestra, and a skene (hut or tent used for changes, as well as entrances and exits) set behind the orchestra, opposite the theatron. The skene was originally a temporary wooden structure, but by the fourth century BCE, it became a permanent stone structure with three doors, which allowed for entrances and exits, as well as the ability to hear violent acts happening out of the audience’s sight. The paraskene was a rectangular area just in front of the skene and was the primary acting area. Greek theatres also had paradoi (passages) to the side of the paraskene leading offstage. The audience used these to enter the theatre, and they were also used by the chorus and characters such as messengers. The rendering below shows a modern design for a Greek theatre, utilizing the elements from theatres of antiquity.

All actors in Greek theatre were male and were probably not paid for their participation in the festivals. Their costumes consisted of typical clothing such as chitons (tunics) and himations (cloaks), as well as masks with wigs attached. These had wide mouth orifices, which aided in the projection of the voice, and were made of lightweight wood, cork, or linen, with exaggerated facial expressions. By changing their mask, actors were able to portray different characters and genders. Due to the fragility of the materials, we no longer have actual masks, but know what they look like thanks to representations found in ancient artwork. The costumes included a form of platform boots called cothurni. These aid in making the characters larger than life, which was useful when portraying heroic characters. It had the practical function of making the actor taller and easier to see.

Greek comic actors were less stately and heroic in appearance, wearing short tunics, often heavily padded, and socci (soft shoes not unlike ballet shoes) which allowed for ease of movement to accommodate acrobatics. Many of Aristophanes’ characters also wore a dangling phallus as part of their costume.

Roman Theatre

As Rome expanded its Empire into Greece, it would have encountered New Comedy. The Romans were excellent at assimilating the best and most useful ideas and items in the countries they controlled through the Empire. The theatrical traditions of the Greeks were easy to adapt to Roman societal standards. Comedy was the most popular dramatic form, and in the mid-third century, the Romans brought writer, Livius Andronicus, to Rome to alter a few elements of Greek comedies to suit Roman tastes. As a result, this gave rise to the two major playwrights of fabula palliata (Roman comedy), Plautus (254 BCE – 184 BCE) and Terence (195 BCE – 159 BCE).

Plautus reworked original Greek comedies to suit Roman fashions. Full of stock characters, unlikely mistakes, and over-the-top humor, they became the basis for Commedia Dell’arte, and Shakespeare used The Menaechmi by Plautus as the foundation for Comedy of Errors. His work did not use a chorus, nor did it deal with political issues. It was farcical and fun, dealing with romantic foibles and missteps.

Terence, a freed slave from Libya, was well educated due to a generous patron. His plays were also based on Greek comedies, as were most Roman plays of the time, but he would often combine two plots from different plays and create an entirely fresh work. He had a more refined, literary style.

Roman theatre, like the Greek model, began as a “festival theatre,” honoring the gods with theatrical performances, vying for audience attention along with the other entertainments offered such as rope walking and gladiatorial combat. The theatre structures were temporary wooden constructions until 55 BCE when permanent stone edifices were built. Like the theatres in Greece, Roman theatres had an orchestra (semi-circular) and a deep, wide stage area behind the orchestra. The permanent facade behind the stage (scaenae frons) had three doors in the center, and one at each end. There were often second-story windows where action would also take place. These theatres were designed to seat large audiences. The largest theatre in Rome held over 40,000 spectators. For comparison, CitiField seats 41,922, and Yankee Stadium seats 54, 251.

The Roman tragedy was not very popular. There were fabula crepidata (adaptations of Greek tragedies) and fabula praetexta (plays with Roman stories). Seneca is the most well-known Roman tragic playwright. The only surviving examples of Roman tragedy are nine plays by Seneca. There is debate about whether they were ever produced in his lifetime, or written as closet dramas: plays intended for private readings rather than public performances. Either way, his work created the foundation on which Renaissance writers, including Shakespeare, structured their plays. Seneca’s influence includes: breaking the play into five parts separated by choral odes, creating the basis for the five-act tragedy; protagonists driven by overwhelming emotion which leads to their downfall, rather than having a tragic flaw; the use of supernatural characters like witches and ghosts; a focus on pithy language, asides, and soliloquies; and the use of violence onstage, rather than describing an offstage violent action as occurred in Greek tragedy.

Throughout much of the Roman era, theatre competed with Roman spectacle for audiences. Gladiatorial contests (munera), chariot racing, and mock sea battles (naumachiae) overshadowed dramatic forms. By the end of the Roman era, new plays were no longer being written for public performance.

Two important texts touching theatre were written at this time. Ars Poetica, by the poet Horace, acted as a guidebook for playwrights. In it, he discusses the importance of keeping comedy and tragedy separate. He dictated that plays should have a unity of time and place in order to achieve a unity of action. He stressed that Unity and verisimilitude were important to achieve believability. “Poets, if they are to be successful, should provide both pleasure and instruction (333–34), and what they write must be more than simply believable, it must be as close as possible to reality: ficta voluptatis causa sint proxima veris (338).” The other text, which heavily influenced the building of theatres in the Renaissance, was De Architectura, by Vitruvius. The ten-volume work covers how to build cities, but also theatres and scenery.

Medieval Theatre

During the collapse of the Roman Empire, Christian objections to immorality in pantomimes and plays discouraged public performances. Without the cultural influence of Rome, the social world of Western Europe splintered into feudal manors and warlords. The rule of law collapsed and theatre, or at least coherent public movements in theatre, stalled. Written records of classical plays survived only as literature in Europe. Actors, dancers, acrobats, and musicians continued to live as itinerant performers, but few records exist of their work.

The Catholic Church kept theatre alive through the institution of liturgical drama around 900 CE. The church introduces dramatic performances to Easter services, acting out the story of the Resurrection. Ironically, the institution that discouraged theater during the collapse of Rome became responsible for its rebirth in the West.

Near the end of the 10th Century, Hroswitha (c. 935 – c.975), a canoness of a nunnery in Gandersheim (Germany), wrote six plays celebrating holy maidens overcoming fleshly temptations. She was a great admirer of the writing style of the playwright Terence but thought his subject matter was not appropriate for Christian readers. At this same time, Ethelwold, Bishop of Winchester, England, issued the Regularis Concordia, a guidebook with instructions for the use of liturgical drama in the Easter celebration.

Early liturgical dramas included simple settings, costumes, and properties, and were performed in churches. The platea (main playing space) was the nave of a church, with more specific locations called mansions placed along the sides. A mansion represented settings for liturgical plays, including Jerusalem, Paradise, and Hell. The audience moved along with the action. These performances relied on singing or chanting to communicate the stories of the plays. The performers were members of the clergy.

The medieval liturgical drama developed directly from the Christian liturgy, focusing on Easter celebrations and the Resurrection. After some time, this led to the Mystery plays in England, autos sacramentales in Spain, and numerous other liturgical plays across Europe, some of which are still performed today.

After 1200, new forms of religious drama began to appear, independent of the liturgy. Outdoor plays, or pageants, were staged in the towns and used the local languages rather than Latin. The performers moved from being clergy members to laymen. By 1350, the Feast of Corpus Christi became a focal point in the spring and summer months for the performance of plays. Religious themes were preserved and expanded to include events from the life of Christ, saints, or stories from the Old Testament. Mystery cycles emerged as episodic plays presenting Biblical history from Creation to Doomsday, in the form of drama. Morality plays, including Everyman, evolved as allegorical lessons of Church doctrine.

As these plays moved outside, they were increasingly produced by religious organizations in the towns along with the trade guilds. The staging required temporary and mobile stages called pageant carts. These were large wagons on which a scenic setting was designed. A new profession was created for these performances— the Master of Secrets. This was the early special effects master who would create fire, flying, or trapdoor effects to increase the theatricality and spectacle of medieval dramas.

When religious dramas moved outdoors, the secular drama also experienced a rebirth, starting with masques performed for the members of the nobility, and mummers’ plays. “’Mummers’ plays‘ are traditional dramatic entertainment, still performed in a few villages in England and Northern Ireland, in which a champion is killed in a fight and is then brought to life by a doctor. It is thought likely that the play has links with primitive ceremonies held to mark important stages in the agricultural year.”

By the late 15th Century, a class of professional playwrights and actors had emerged under the patronage of wealthy members of society. Theatre patronage soon became an aristocratic badge of prestige. With the fall of Constantinople in 1453, many scholars fled west to Italy, bringing with them vestiges of classical artistry and writing salvaged from the libraries of the Eastern Empire.

The Renaissance and the Beginning of Professional Theatre

The 15th Century saw the rise of Humanism, the fundamental impulse driving the Renaissance. The severity of medieval social hierarchies and the focus on the divine gave way to a philosophy of tolerance, and admiration for human qualities and accomplishments. With the fall of Constantinople in 1453, classical texts became available due to the “rediscovery” of the ancient manuscripts as they came back to Western Europe. The work of Vitruvius was interpreted by Renaissance architects and theatres like Andrea Palladio’s Teatro Olimpico in Vincenza, and Aleotti’s Teatro Farnese in Parma were created to imitate Roman theatre forms.

Although the birthplace of the Renaissance, the focus was more on architecture and fine art at this time and less on plays. However, it cannot be denied that Italianate scenic developments pushed the design world forward. Serlio’s single-point perspective settings, the development of the proscenium arch, wing and drop scenery, and the raked stage (higher in the back than the front, thus our Upstage and Downstage), cemented Italy’s place in the development of modern theatre.

Italy may not have fostered great playwrights at this point in time, but one cannot overlook the development of commedia dell’arte. This actor-driven theatre, with improvisation based on a set of stock characters and a loose plot line to give the story some structure, flourished at this time and has continued to this day. Using trained actors, masks, and a predictable plotline, commedia dell’arte would often include suggestions from the audience. The stock characters and broad comic style were popular across Europe, and influenced comedic writing, particularly in France from the 16th to the 18th century. Most of the plotlines revolve around the mischief of servant characters (zanni) and the foiling of the vain, pompous, or lecherous. Stock characters include Capitano – the braggart soldier, zanni – crafty servants (Arlechino and Harlequin was most popular), Pantalone – an old man, often greedy and a fool, and Dottore – a doctor, sometimes a drunkard, often just foolish. These characters (and others) have been richly echoed by playwrights such as Shakespeare and Molière.

The Renaissance arrived in England a bit later than in southern Europe. The late Tudor period became the golden age of English theatre, yet elements of medieval theatre overlapped. The Greek and Roman classical texts eventually reached England and influenced many of the playwrights there. Ralph Roister Doister by Nicholas Udall owes a great deal to Plautus and his Braggart Soldier. Elements of that same play can be felt in Shakespeare’s character Falstaff, just as the influence of Seneca may be seen in Hamlet with the violent fights, ghosts, and soliloquies.

Just who wrote the plays required to sustain a Golden Age of Theatre? You are probably familiar with William Shakespeare, playwright, actor, and part owner of the Globe Theatre, but there were many others writing at this time as well. The University Wits were an informal group of scholars (all were university educated, or had studied law at the Inns of Court) who applied classical standards to the needs of a strong contemporary stage. They were: Robert Green (1558-1592); Thomas Kyd (1558-1594), who wrote The Spanish Tragedy, c. 1587, which was one of the most popular plays of the 16th Century; John Lyly (c. 1554-1606) known for prose comedies; and Christopher Marlowe (1564-1593), the contemporary of William Shakespeare, famous for his prose style and subject matter, known for The Jew of Malta, Dr. Faustus, and Edward II. His fame might have rivaled that of Shakespeare had he not died in a fight at the age of 29.

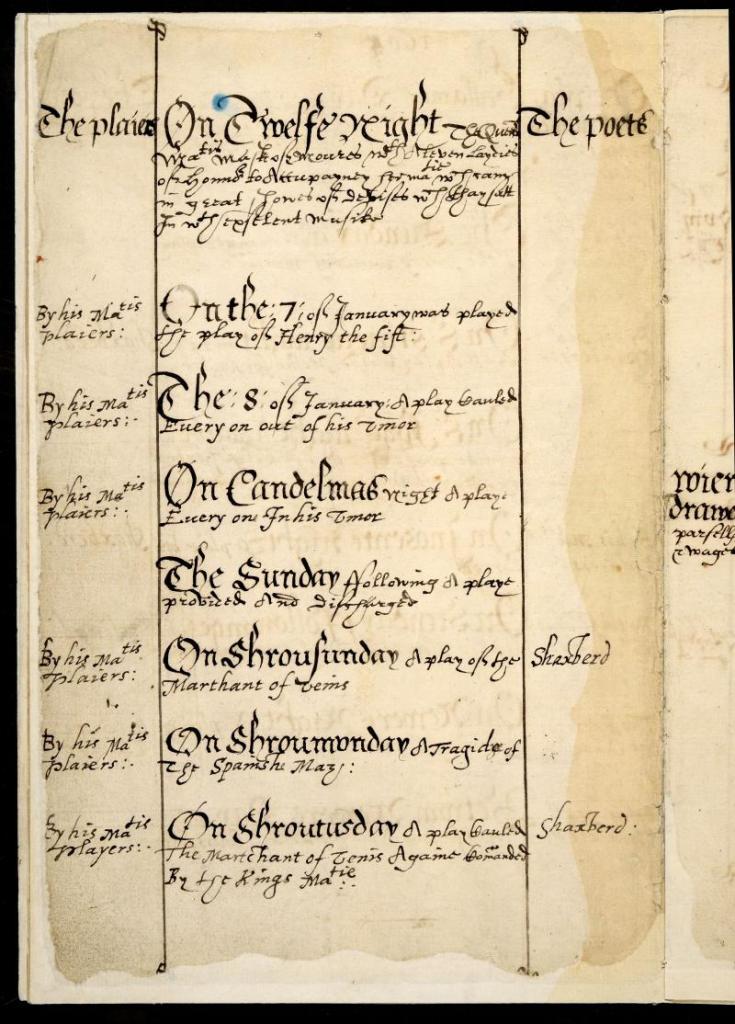

Acting did not fall into the easy format of the medieval guild, so Elizabethan acting troupes required patrons, or they could be arrested as vagrants and vagabonds. Noble patronage meant protection and was a level of respectability, yet it included restrictions. All professional acting troupes had to be licensed and each play had to be approved before it was performed. The Master of the Revels awarded the licenses to perform in London and kept a daily account of approved plays, as may be seen in the accounts of Edmund Tylney, Master of the Revels in 1604, shown below.

James Burbage was the head of the first important troupe, the Earl of Leicester’s Men, licensed in 1574. Later important troupes were The Chamberlain’s Men which included Richard Burbage and William Shakespeare, The Lord Admiral’s Men, Christopher Marlowe’s troupe, and The Queen’s Men. As in classical theatre, all members of Elizabethan acting troupes were male, with boys playing the female roles. In 1576, The Theatre, the first commercial public theatre, opened in Shoreditch, outside of the City of London. Built by James Burbage, very little is known about the actual theatre, but after it proved a successful venture, other theatres were rapidly built.

Most of what we know about Elizabethan theatres comes from a few illustrations, (most made at a later date) some descriptions from builders’ records, a few legal documents, and recently, excavations of The Rose, and a few others. There were outdoor theatres, theatres with covered seating and open yards for “groundlings” (audience members who paid a small price and stood to watch the performance), and private houses (indoor theatres for a select audience). There may have been no “one size fits all” theatre during the reign of Elizabeth I.

Meanwhile, in Spain, a parallel development arc occurred. Religious dramas, called autos sacramentales were performed, representing the mysteries of Communion and the Eucharist. These had a strong similarity to the Mystery Cycles and Morality plays of England. Allegorical characters of Sin, Faith, Death, etc., were intended to guide audience members to be better members of society. These were produced by trade guilds, but they were still religious. The productions took place on carros, large moveable wagons, similar to pageant carts. These traveled a specific route, making planned stops along the way.

The 15th Century saw the development of popular theatre, with many playwrights and a great prolificacy of plays being produced. Comedias Nuevas (New Comedy) were secular plays in three acts using history, popular culture, mythology, and Bible stories as source material. The large casts included characters of nobles, ladies, and comical servants. Performances took place in corrales, public, open-air courtyards or patios between three houses, with covered seating along the edge of the courtyard. Women would often watch from the windows of the houses. The structure of the corrales was similar to the seating at some Elizabethan playhouses. One major difference in the Spanish and English styles, however, was the inclusion of women in the cast. There were restrictions that varied over time but included that there be no cross-dressing and that the women be wives or daughters of company members.

There were many popular playwrights at this time in Spain, but the main three were Miguel de Cervantes, Lopes de Vega, and Pedro Calderon de la Barca. Miguel de Cervantes (1547 – 1616), may be best known to the English-speaking world for his novel, Don Quixote, but he was one of Spain’s early successful playwrights. He penned thirty comedias, but only two of his plays survive; The Traffic of Algiers and The Siege of Numantia. Lope de Vega (1562 – 1635), was a pioneer of the Golden Age of Spanish theatre. He is credited with fixing the structure and the themes for Spanish comedia. A prolific writer, he created five hundred plays, nine epic poems, four novellas, three novels, and three thousand sonnets. Still popular is his play, Fuente Ovejuna (The Sheep Well). Pedro Calderon de la Barca lived a varied life, having been a soldier and a priest as well as a playwright. His one hundred and twenty comedias and eighty autos sacramentales were polished and refined works. He is best known for his play La Vida es Sueno (Life is a Dream).

French Neoclassical Theatre and the Rise of Romanticism

French theatre in the 17th and 18th Centuries was a polyglot of English, Spanish, and Italian theatrical practices. Neoclassical Italianate theatre design emphasized perspective and visual balance. Large casts and complex plots, as found in English and Spanish theatre, became the norm. There was a decided lack of specificity until the neoclassical ideals of Italian theatre were adopted in France. The tenets of neoclassicism mimic the ideals for theatre laid out by Horace in Ars Poetica: purity of genre—tragedy and comedy should not be mixed; verisimilitude—the story should have the appearance of truth and the actions be probable; decorum—a character’s behavior should stay in keeping with their sex, social standing, and occupation; structure—the play should have five acts; and purpose—drama should teach as well as please.

In the early 17th Century, French theatre struggled due to political instability in the country. In the 1630s, an educated class of playwrights began to emerge, and at the request of Cardinal Richelieu, in 1636, they established the French Academy, a group limited to forty writers and intellectuals. The Academy was given a royal charter in 1637. Pierre Corneille (1606 – 1684) wrote comedies early in his career, but it was his play, Le Cid, which brought him to the attention of the French Academy. This tragicomedy was based on the Spanish play, Las Mocedades del Cid, and Corneille applied neoclassical ideals to the adaptation, trimming it from six acts to five acts, and condensing the action into a twenty-four-hour period. He was criticized by the French Academy for mixing genres, and for putting too much action into one day, stretching the limits of believability.

After the Academy’s ruling on Le Cid, strict neoclassicism could be seen in the work of Jean Racine (1639 – 1699). Trained in the classics, he updated Aristophanes’ comedy, The Wasps, into the Litigants. He adapted Euripedes’ tragedy, Hippolytus, into a pure example of neoclassicism, Phaedre. Phaedre is the center of the conflict, and the play focuses on her love for Hippolytus. The actions are plausible, the events occur in one place and over a few hours of time, and ultimately, evil is punished.

King Louis XIV was a great patron of the arts, and during his reign (1643 -1715) bestowed Royal patronage on theatre in France. This led to the construction of large public theatres in Paris, as well as the establishment of resident acting troupes, including an Italian commedia troupe. All public and court theatres in Paris were built or renovated at this time to have the Italian proscenium arch. Another significant change during this time was the inclusion of women as onstage performers.

What Corneille and Racine did for French tragedy (setting the standard for the next century), Molière did for French comedy. Jean Baptiste Poquelan (1622-1673), aka, Molière, was a favorite of Louis XIV. In the 1660s he successfully combined neoclassicism, commedia dell’arte, and French farce in plays that ridiculed social and moral pretense. His comedies were purely French and of his own devising, based on his experiences and observations, rather than reworkings of older Italian or Spanish plays. They were fresh and wickedly funny. Plays like Tartuffe (1664), The Misanthrope (1666), The Bourgeois Gentleman (1670), and The Imaginary Invalid (1673), have made Molière one of history’s most famous and enduring playwrights.

Restoration Theatre in England

After Shakespeare, there was a decline in English theatre. The onset of the First Civil War led to the closure of theatres in 1642 by the Long parliament. King Charles I had lost his head, and Charles II was in exile in France. Oliver Cromwell and the Puritans banned theatre.

In 1660, Charles II returned to the throne and encouraged artists to employ the theatre conventions he saw in France: Italianate staging, the proscenium stage, and elaborate scenery. These innovations were necessary due to the neglect of the old theatre buildings, the out-of-date plays, and tired theatre conventions. Restoration Theatre also introduced women to the English stage, with pioneering actresses, Elizabeth Barry and Anne Bracegirdle, leading the way.

Another trailblazer who should not be forgotten is Mrs. Aphra Behn. Hroswitha may have been the first female playwright we know of in Western theatre, but Mrs. Aphra Behn was the first woman to make her living as a writer. She wrote poems, pamphlets, plays, and novels. Her early life was spent in Surinam, West Indies. Her first novel, Oroonoko, was based on her time there. She moved to England after her father’s death, and married Mr. Behn, a Dutch merchant, but was soon widowed. She became a spy for Charles II during the war with the Dutch, but ended up in a debtors’ prison, as the King apparently did not pay her. She wrote to support herself, creating twenty plays, (some bawdy and showing scenes in brothels) but she was writing for a commercial audience and needed her words to sell tickets. She was told her writing was scandalous, and replied that it would not be so were she a man. The Rover, with its female-driven plot, gives Aphra Behn the moniker of an early feminist.

All women together, ought to let flowers fall upon the grave of Aphra Behn…for it was she who earned them the right to speak their minds…Behn proved that money could be made by writing at the sacrifice, perhaps, of certain agreeable qualities; and so by degrees writing became not merely a sign of folly and a distracted mind but was of practical importance.

Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own (1929)

The Restoration plays with their French influence focused on aristocratic themes, social intrigue, and the sexual reputation of its characters. Conversely, characters in Comedies of Manners valued wit over morality and reputation over virtue. Prominent playwrights of the time included William Congreve (1670 – 1729), William Wycherly (1641 – 1716), and Oliver Goldsmith (1728 – 1724). By the late 18th century there were more changes. The satirical edginess of English restoration comedies gave way to sentimentalism, with an emphasis on visual form over substance.

Meanwhile, across the pond in 1665, William Darby’s Ye Bare and Ye Cubb was the first English language play presented in the colonies. 1730 saw the first play by Shakespeare in the New World, with a performance of Romeo and Juliet in New York. The Virginia Company of Comedians, the first professional theatre company in the colonies, was established in 1751 in Williamsburg, VA. and in 1766, The Southwark Theatre, the first permanent American theatre, was built in Philadelphia.

19th Century Melodrama

During the 19th Century, melodrama was the primary form of theatre, reaching the height of popularity in the 1840s. The characteristics of melodrama include: the use of music (leitmotifs) to heighten the emotional impact of the play; moral simplicity in which good and evil are embodied in stock characters; special effects such as fire, earthquakes, and explosions; episodic format in which the villain poses a threat and the hero and heroine eventually escape and live happily ever after.

Dion Boucicault (1822-1890) wrote two of the most successful English-language melodramas, The Corsican Brothers (1852), based on a French novella by Alexandre Dumas, and The Octoroon (1859), which was one of the most popular antebellum melodramas in the United States, second to Uncle Tom’s Cabin. His work was witty and sentimental, with spectacular endings like train crashes, burning buildings, and earthquakes. Boucicault was the first playwright in the United States to ask for and receive royalties for performances of his plays. This was critical to the establishment of The International Copyright Agreement of 1886.

New trends in the theatre of the 19th Century included the creation of “stock companies” in which a group of actors played a variety of roles in a large number of plays each season. They received a set salary for the season, regardless of the roles they played. Another trend was the star system, where English actors would tour with resident companies, making huge salaries. After 1850, the size of the repertory decreased as the length of runs increased. It was harder to recoup investments, and some actors in the company might not be in some of the shows, yet still received their salary. New York became the theatrical center of the United States by the 1880s, with actors going there to be hired. By 1900, the repertory system disintegrated and was replaced by the single play/long run. The large size of theatres in New York encouraged spectacle rather than intimate dramas.

Realism

Realism in theatre came in response to the social changes taking place in the mid to late 19th Century. Men like Charles Darwin, Karl Marx, and Sigmund Freud helped shape the way society viewed the human condition. Theatre, then, became a mirror of society, acting as a direct observation of human behavior. Scenery and costumes became historically accurate, and scripts were written about socially uncomfortable issues. Henrik Ibsen (1828 – 1906), is known as the father of modern realistic drama. He discarded asides and soliloquies in favor of exposition revealing the character’s inner psychological motivation. His characters are influenced by their environment. His plays tackled topics like the role of women in society, syphilis, euthanasia, and war. He became the model for later realistic writers. A Doll’s House, written in 1879, was banned in many countries, because the protagonist, Nora Helmer, leaves her husband and children at the play’s conclusion.

Other realistic writers include Anton Chekov (1860 – 1904) in Russia, who wrote plays about psychological realities where people are trapped by their social situations. Examples: Three Sisters (1900) and The Cherry Orchard (1902). George Bernard Shaw (1856 – 1950) in England was known for his sharp wit. He wrote comedies that were thought-provoking and challenged societal norms. In Mrs. Warren’s Profession, Shaw uses prostitution to expose the injustice and hypocrisy in British society. In Pygmalion, later turned into the musical, My Fair Lady, he reveals the superficiality of society by having a flower girl be elevated to a lady of society, merely by changing her pattern of speech. Shaw was specific and opinionated about the production of his plays and is one of the premier playwrights of the 20th Century.

Modern Theatre

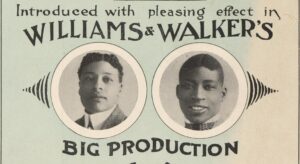

For much of the 20th Century, realism was the most prevalent form of theatre. Musical theatre grew out of the tradition of minstrel shows and vaudeville and became the most commercially popular form of theatre. Early in the century saw the establishment of African American Theatre. Bert Williams and George Walker had been a successful comedy team in vaudeville. In 1903, Williams and Walker opened In Dahomey, the first full-length, all-black musical on a major Broadway stage. It ran for 1,100 performances and then went to England. A truncated version of the show was performed for the King at Buckingham palace on June 27, 1903. Bert Williams joined Ziegfeld’s Follies of 1910 and became the first African American performer in the Follies. By this time, he was earning as much money as the President of the United States.

The Harlem Renaissance was a rich period for the arts in New York. Centered in Harlem, it spanned from approximately 1918 through the mid-1930s. African American arts and literature gained national attention. It celebrated the emergence from enslavement and cultural ties to Africa. Prominent performers included Josephine Baker, Louis Armstrong, Paul Robeson, and Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. Of writers and playwrights at this time, Zora Neale Hurston, Eulalie Spence, and Langston Hughes number among them. Langston Hughes wrote his play, Mulatto, in 1935, and it ran on Broadway for 373 performances, making it the longest-running African American drama until A Raisin in the Sun in 1959.

Another 20th Century playwright, Eugene O’Neill (1888-1953), is credited with raising American dramatic theatre to an art form respected around the world. His career had three distinct periods: realism, where he mined his experiences as a sailor; expressionism, when his plays were influenced by philosopher Freidrich Neitzsche, psychologists Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, and playwright August Strindberg; and a return to realism, where he again used his own life experiences. O’Neill is considered America’s premier playwright. His work was much lauded, and in 1936 he won the Nobel Prize for Literature. He was awarded four Pulitzer Prizes: (1920) Beyond the Horizon; (1922) Anna Christie; (1928) Strange Interlude; and (posthumously in 1957) Long Day’s Journey Into Night.

Tennessee Williams had several Broadway successes during his career. Along with O’Neill and Arthur Miller, he is considered to be one of the most important American playwrights of the 20th Century. He wrote from his life experiences, broaching topics like homosexuality, promiscuity, and emotional abuse in his plays. His strong female characters are evident from the beginning of his career, as seen in The Glass Menagerie (1945). In 1947, A Streetcar Named Desire opened on Broadway with Jessica Tandy and Marlon Brando, and it won the 1948 Pulitzer prize. His second Pulitzer Prize was awarded for Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, in 1955. Both were made into motion pictures.

Contemporary Black Theatre

In 1965, following the assassination of Malcolm X, LeRoi Jones, later Amiri Baraka (1934 – 2014), established the Black Arts Repertory Theatre in Harlem, NY. His desire was to create a Black aesthetic in American theatre and inspire future black theatres. The mission was to make theatre, “by us, about us, and for us.” Many of his plays, including The Dutchman, were staged there in the 1960s.

August Wilson (1945 – 2005) earned popular and critical success with his plays about the African American experience. His “American Century Cycle” (also called The Pittsburgh Cycle) is a series of ten plays, one for each decade, chronicling racial issues in the twentieth century. Wilson is quoted as saying, “I write about the black experience in America…because it is a human experience. And contained within that experience are all the universalities.”

Is That It?

This is just a brushing of the surface of the rich history of theatre. A chapter is not enough space to write about the marvels of performance and creation that have occurred across the centuries, but I hope this piques your interest and possibly inspires you to read some of the plays mentioned in the different eras.

Laura Cole is the Director of Education and Training at the Atlanta Shakespeare Company at the Shakespeare Tavern Playhouse.

Laura received her Bachelors’ of Science in Acting from Northwestern University. Laura has worked in professional theater as an actor, teacher, and director for 30 years. She has taught Shakespeare in performance with Shakespeare & Co Lenox, MA, Folger Library DC, the Southeastern Theatre Conference, Columbus State University, GA Perimeter/GA State University, Georgia Tech, and New York Classical Theatre. She has consulted on Shakespeare in the classroom for Agnes Scott College, Emory University, University of North Georgia, and Georgia Tech, among others. Most recently she has taught playing Shakespeare with Pre-K children in shelters and college students earning degrees after returning from incarceration. She also mentors women artists at all levels of professional growth. As a professional actress, she has performed Internationally, Off-Broadway, and in regional and Atlanta theatre throughout her career and has directed numerous plays at the Shakespeare Tavern Playhouse in Atlanta. She has designed and taught all of ASC’s education programs and consults on using language and the plays of Shakespeare to explore the creative work of businesses and educational institutions throughout the Southeast.

Kiara Pipino:

Can you please tell me what got you into Shakespeare?

Laura Cole:

Oh, wow. Well, when I was in middle school, so seventh or eighth grade, I was really, really shy. And my mom put me in a children’s leader program, ACT, in Athens, Georgia, which is where I grew up. It was an excellent program for that time. One of the things we did in the program was performing cut-down Shakespeare versions of plays, or musicals, every year. I was in a production of Romeo and Juliet. I didn’t get to play Juliet, and I remember thinking that I gotten that role because “I’m going to be a professional, I’m professional.” But of course, I wasn’t a professional, nor was I Juliet! I was “third Capulet from the left” and I had a pretty costume and…. I didn’t know what I was doing.

Later that year, I think it was in the fall, Mrs. Martha Lord, my ninth grade English teacher, whom I really liked was very excited when she learned I was in the production. We were reading the play in class – every Georgia student still does read Romeo and Juliet in ninth grade. She said I was doing Shakespeare the right way – meaning performing it and being involved in a play rather than just reading it. And since I loved her so much, I thought I needed to pay attention to this Shakespeare dude.

And then I don’t think I did any other Shakespeare in my entire high school career, but it was one of the first things I studied when I was at college as an actor at Northwestern. We spent a lot of time with the Greeks and Shakespeare. It wasn’t until we were in the junior year that we went to modern texts.

I took a bunch of Literature courses, Performance Study courses and decided that when I graduated and went to New York or LA or wherever, I was going to go to be an actor that I wanted to do Shakespeare. Then, it happened that I moved back to Atlanta, dove into its theatre scene and did not get cast or perform in Shakespeare for, I think, eight years. Finally, I got cast my first Shakespeare play, The Comedy of Errors, and again I did not know what I was doing… but I never looked back.

KP:

What were you cast in The Comedy of Errors?

LC:

Was Luciana. And I remember being in the last scene with both the Antipholus, where there’s all these long speeches about what had happened. Luciana only has one or two lines in the scene, but I had no idea what people were talking about, I was so confused because I actually didn’t know how to read Shakespeare as an actor, really. The director, Jeff Walkins told me, “Just look at the person who’s talking.” And that is the best advice I can still give to any young actor! Don’t try and “take the stage”, just look at the person who’s talking.

After that production, I started getting cast in a lot of different roles and didn’t look back.

KP:

And then you started your own theatre company.

LC:

Well, I started working at the Atlanta Shakespeare Company, directed by Jeff Watkins, who also started it. I was hired to do modern work. We had about four good seasons. Then I started getting cast at Atlanta Shakespeare and in the 2000/2001 season, I started the Education Department. I’ve been doing education and training ever since.

KP:

Can you talk about Atlanta Shakespeare?

LC:

At the Atlanta Shakespeare company, based at the Shakespeare Tavern Playhouse we do what is commonly called or referred to as Original Practices. That means understanding Shakespeare’s original playing conditions. We investigate what was going on for The King’s Men or The Lord Chamberlain’s Men in the world of Elizabethan and Jacobian England that might have prompted some of the plays or why Shakespeare wrote certain plays about certain characters rather than other plays about other characters. Other factors of Original Practices are understanding what costumes might have looked like, how they made sound effects like an offstage battle or a party, both of which happen in Macbeth. We wonder what a ghost looked like when you performed at two or 3:00 PM in the afternoon, under the sun, in the middle of the day…What did the ghost of Hamlet’s father look like? Did they use smoke as fog? Probably. Did they have real sets of armor? We don’t know. What kind of props did they use to tell stories? How did the “thunder machine” work? What did the storm on the heath look and sound like to Shakespeare’s Elizabethan audience?

We invest heavily in understanding all of that and it extends to the way we look at Shakespeare’s text. We use the First Folio in a modern typeface by Neil Freeman to begin with. We also use the Arden and the Folger, but we start with the text that was printed a few years after Shakespeare’s death, even though that’s probably not exactly what Shakespeare wrote… but we can’t know that for sure. It’s as close as we can get to the original.

Our stage is what we call a “Globe inspired” Playhouse. It’s not round, it’s rectangular.

We don’t use recorded sound.

We do use lights though, differently from Shakespeare’s company and… we do have air conditioning because it’s in Georgia! Other than that, we do what we think might have been the way Shakespeare approached and produced his plays. One of my ongoing jobs within the company is finding the research by scholars that might inform our practices even more. For the Shakespeare nerds out there my favorite scholar is Andrew Gurr.

Of course, we rarely do single-gender casting. And when we do, it’s not all men, it’s all women, that’s a conscious, not Original Practice. But the costumes usually look like Elizabethan or Roman/Greek costumes- depending on whether we are doing Othello or Julius Caesar. We don’t do modern costumes because rich Elizabethans and the official patrons of a theatre company always donated their old clothes to their “pet” companies and then the artists made them into costumes. We investigate how the actor-audience relationship might have been, when the audience could see the actors and the actors could see the audience and the audience sees each other.

KP:

You mentioned that every child in ninth grade studies Romeo and Juliet or, more broadly, Shakespeare. Why do you think that is? Why do you think Shakespeare is so popular in the school curriculum?

LC:

Well, for both good and bad reasons. There is a colonialist and not-so-positive reason, it being Shakespeare is part of the Western European Canon, along with the King James Bible, which was written during King James reign. James was Shakespeare’s king.

But on the other hand… think about it… Romeo and Juliet is about two teenagers that fall in love and their parents aren’t real happy about it and then… tragedy. And The Comedy of Errors is about what happens when somebody gets really jealous and the other person doesn’t understand why you could possibly be jealous… and there’s twins! And then there is The Tempest, which is a play about the relationship between a dad and a daughter and meeting new people.

In his plays there’s this real dichotomy between real normal relationship problems and storylines that deal with what makes a good king, or why must this ruler die? And then, there is all this great comedy and a lot of unfamiliar words that make really beautiful poetry.

Once I started to understand it better, I realized how fabulous it was to speak it. As a teenager, that kind of tactile experience of language was really exciting. Nowadays it’s easy to find Shakespearean performances: teachers can show videos or movies or take their students to a matinee performance. And then there are tour shows that go all around the country.

KP:

You just mentioned the language. A lot of people would argue that Shakespeare’s language is actually a barrier. How do you feel about that?

LC:

People used to say Shakespeare’s for everyone, and it isn’t. In terms of the language, yeah, it can be really complicated. It’s early modern English, for the most part. I don’t think that even Shakespeare’s original audiences would’ve understood and recognized all the Latin words in his plays, let alone all the words he made up. They weren’t different from us at all, except at that point the English language was just coming together in a way we would recognize. A mentor of mine says that Shakespeare’s English was 400 years “young” compared to our 400 years experience with it.

I think the experience of the performance gives a better sense of what the actors are saying and by the way, they’re saying it, we get the meaning of the words. My mom says that actors at the Tavern use “Shakespeare hands” to help the audience understand. We use gestures for emphasis, to fight with swords, and to help explain more of what we mean when we talk. An example: a good actor might shake a fist at the heavens when they are angry at their gods rather than just look up and yell. Reading aloud in class is nothing like watching a play onstage, or being IN a play.

At times, it gets to be real stuffy and hard to understand. That’s kind of the reputation that Shakespeare’s language has in our modern times. Also, the way we teach Shakespeare depends heavily on the teachers. Sometimes, teachers tend to teach it the way they learned it, in a sort of literary way, rather than making it a new experience for their students. Learning Shakespeare in an English class provides an insight on the language itself, but not necessarily on its granularity and excitement, which can only come from experiencing the text in production or by performing it yourself. That’s where acting comes in, especially when it’s in the form of direct address to the audience and there’s no design element that might visually contradict what the actors are saying. If you are performing the text, you are exclusively focused on what is being said, and by who, rather than on the visual elements.

One of the reasons why Shakespeare’s language has a bad reputation is that for the most part in schools you don’t perform it, you read it, sitting at your desk in a classroom. That makes it really hard to understand it.

KP:

Yes. There’s something about performing it that makes it alive and clarifies it because you have to make sense when you’re doing it.

LC:

It has to. I tell my actors, even if the words are not familiar to this audience of ninth and 10th graders, we still can put our emotional spin on them. We can still use our actor’s spidey-sense to give them an underlying understanding of the emotions that are generated by the characters. The kids can see that and they get the gist of it. They get that Juliet’s really upset, even though they don’t understand what her dad just told her. They get that Dad’s mad at Juliet and that’s bad. Even if we can’t understand any of what Lord Capulet is saying when he’s threatening to hit her or banish her, or just to toss her out into the street… all that beautiful language, but we get what’s going on. Good actors can make it work.

KP:

How do you feel about the rewritings, Shakespeare’s modern adaptations?

LC:

I deeply admire the idea and the goal. I have seen several “play-ons” and I just directed one.

Giving new playwrights a chance to interact with Shakespeare’s plays, their language and stories and seeing how they can make Shakespeare’s language more approachable is exciting.

I did discover, though, as a director and as an actor myself, that in a “play-on” I had to explain and research more of what the emotions, or the character stuff that was going on in certain passages were all about, because the truly descriptive Shakespearean language was missing or so modified that some gut-level sounds are gone. Modern English tends to simplify, sometimes too much. The original words give you a more tactile experience, in the way they are structured with Iambic Pentameter. So as an actor, you have to do more research on your own when you are not working on the original, I think. When the rhythm of the line is interrupted, there is something that goes missing and the character tends to sound flat. Shakespeare used rhetoric to the character’s advantage, like alliteration or onomatopoeia (there are a ton of “Figures of Speech” Shakespeare used in his plays,) and you usually lose at least of that in translation. It has been proven that Shakespeare’s use of rhetoric also helped the audience stay focused on what was going on: certain sounds or figures of speech would work subliminally on the brain and would keep the audience invested. There is a whole study about it… this is a link to an article about the paper- I couldn’t find the original paper! https://folgertheatre.wordpress.com/2011/11/21/shakespeare-changes-your-brain/

KP:

In schools, when they study Shakespeare, they usually use heavily edited and translated versions. How do you feel about that?

LC:

I live in Georgia. And when we do a school matinee of Romeo and Juliet, we cut the text for time purposes because for the matinee performance we guarantee you’re out by 1:00 PM and that way you can make the afternoon bus schedule. Even a shortened version of Romeo and Juliet is better than no live performance at all. Of course, you lose something, but at times it is worth telling the central story and not worrying too much about what is explicit in the language. All the plays are different in that respect, but Romeo and Juliet is a useful one to talk about. There are times where I’m directing it and an actor has a very aggressive interpretation, which is not incorrect. And I’m like, “You know what, I’m not comfortable with that in this scene. Say the language, but don’t be so explicit or graphic. Back off on that so that I can wonder. So that the audience can wonder.” And then, there’s a lot of Romeo and Juliet that we can cut. In some of the longer plays, like Richard III, “crazy” Queen Margaret, the “ex-queen,” used to be cut a lot, or completely. But if you don’t have Margaret cursing and calling Richard III names, you don’t get how awful he has been to the women in that play. If she doesn’t have the litany of who killed who and how he killed all of her family, then his impact as a villain is really lost. But you can shorten some of what is said so that the audience doesn’t sit there for three hours struggling because modern Americans are now used to 30 second Tik Toks. It’s a balancing act.

And there’s also No Fear Shakespeare which has the standard text on the right and then a really modern translation on the left. That can be a good compromise when teaching Shakespeare, I think. Teachers say it helps the students really understand what is going on in the play at any given time. So I think that helps, although when you’ve got the explanation on one side of the page, why do you have to work at all to understand what it really means to you specifically? It takes a whole world of learning away from students. I wholeheartedly support EVERYTHING a dedicated teacher does to bring the plays to life for students.

A good compromise could be not to teach the whole play, but just key scenes. Do the parts that you’re really interested in and that you think your students will like. Then you can dig into the language, characters, and situations and perhaps figure out what it means without a more literal modern interpretation.

KP:

Your company does Original Practices, with minimal design and true to the time period. How do you feel about all of the modern takes and interpretations of Shakespeare’s plays?

LC:

I love a good, spectacular vision on stage. I’m a theatre professional and I love the art. I love seeing what brilliant minds come up with. When I’m a ninth grader encountering my first Shakespeare play in a performance, I might not be able to process some of the visuals the way I can as an adult.

There was a very well-reviewed production of Much Ado About Nothing, at The Public Theater in 2019, directed by Kenny Leon, who is from Atlanta. It really moved that play into a whole new world. The state of Georgia, in fact!

That production really brought a particular joy and storytelling to the play that was very unique, but still so much an essence of the original Shakespeare.

Some of the very best productions with any kind of values that are closer to Original Practices have little to no set design at all. I did some outdoor Shakespeare where we were in a park, but not on a stage. We moved from one part of the park to the other and the audience was all around us and they followed us. And the story still was very clear because all we had was the language and we spoke directly to the audience most of the time. That is the actor-audience relationship in a nutshell.

I think sometimes modern concepts superimposed on a Shakespeare play might ruin the audience’s experience of it for the sake of the exercise of the artistic freedom of the artists.

I remember hearing an artist who was in a production of Macbeth, which they did it following the Suzuki/Viewpoint aesthetic. When his dad came to see it, he was really confused. He had no idea what was going on. And the actor realized, you know what, sometimes the stuff that we as artists like to bring out interrupts other folks’ understanding of the basic plot, and without understanding it may not enjoy it.

KP:

At the Tavern, what’s your process when you work on a production?

LC:

20 years ago, there were a handful of actors that worked there regularly. We didn’t produce year-round, we only did about five, six, maybe seven shows a year. When I started the Education Department, I started building a curriculum based on training I received with a company in Lenox, Massachusetts, called Shakespeare & Company who specializes in actor training in a way that honors Original Practices. When I came back, I started offering this as actor training, because I was experimenting with what I had been learning. It really caught on, it really made an impact. And I had some of my master teachers come down here and teach acting classes. And then we started offering it to actors every time we did a show.

We usually audition for every show, although sometimes some roles are assigned to company members. Since 2002, we have the Apprentice Company, which is a program for post-undergraduate actors who would like some extra training on Original Practices or Shakespeare or would really like to apprentice with a theatre company. You can also call them interns, but we call them apprentices because that’s what Shakespeare called his young actors. They come from all across America. Atlanta is a hot theater and movie/tv destination now.

Our apprentices do it all like they did in Shakespeare’s time. They work on scenes, they learn fights, mop the lobby, seat the audience… they get cast in productions, and many stay with the company past their graduation from the Apprentice company.

Everyone in the company does a little bit of everything, from acting to directing, to administration and contributing to the entire life of the building, the entire life of the company, as well as the teaching and training of the next generation. I think that out of 22 staff members, only four or five are not performers. Everyone else is a performer, whether they were hired to be the director of development or like me, to be an actor and a teacher, we all perform. We perform year-round, a different show every month.

KP:

Let’s go to something a little more personal, what is your favorite Shakespeare play?

LC:

Oh dear.

KP:

Oh dear.

LC:

Well…okay but… don’t tell the other plays!

I have always adored Othello. I’ve directed it and I’ve been in it, although I never played Desdemona, which by the way has always been my dream role. But I also usually fall heavily in love with whatever play I’m rehearsing or directing… When I played Hermione in the The Winter’s Tale, I loved the through line of a marriage dynamic, I loved that language, and doing that really difficult performance of a marriage. I also really love Love’s Labour’s Lost. It was the first play where I said, “Hey, I want to direct this.” And I did! I had beautiful music and I was so struck by that play. It was a beautiful, beautiful, beautiful production. We remounted it, too. When I see that play performed, I fall in love with it all over again. Because there’s just something about its ridiculous poetry that I really love. And the idea that four young men could abandon food, sleep, love, and women for three years of nothing but study and contemplation? Ridiculous!

Another favorite role of mine is Lady Macbeth. I’ve played her a lot… and when I tell people that I identify with her, they give me a weird look. And I say: “I am a happily married woman. And I think my husband deserves the best. I want the best for my husband.” So, I get why Lady Macbeth does what she does. She loves her husband and wants the best for him. However, I am not a murderer or a psychopath, so I’m not going to kill anybody to get a promotion for my husband. But I see the way that marriage seems to be a partnership at the beginning where they both get a lot of say.

KP:

Another personal question. What is your least favorite Shakespeare play?

LC:

I really don’t have to see The Two Noble Kinsmen ever, ever again. That forced marriage at the end… How do we get around that?

There are some plays that I have really connected with over the years as an actor, but that I really don’t want to direct. One of those is The Taming of The Shrew. And of course, right now it’s a tough title. I had a lot of great success playing Kate, the lead role, but I don’t really want to direct it anytime soon, not because I don’t like the play, but rather because my memories of it are tied to a very particular point in my career.

Then…. I don’t know that I’d ever want to see Coriolanus again either, just because there’s a lot of anger in it…. although I would love to play Volumnia, the mother. I would like to be in it, but not to direct it. I also got an honest-to-god sword wound during rehearsals. Stitches and everything! I am very proud of that.

KP:

Last question. Why do you think we should keep teaching Shakespeare? Not just in high school and middle school, but in college. Why do you think it’s important for young people to go to the theatre and watch a Shakespeare play? Instead of sticking to Tik Tok?

LC:

Because Shakespeare is going to grab hold of you and make an impression on you that will stay with you forever. I said, it’s not for everybody ever, but most theatre makers hope to do it so that anybody that wants to can connect with it in whatever way works for them. There are endless artistic possibilities when approaching a Shakespeare play, so artists can really make an impact on the production. This is not necessarily true for modern and contemporary plays, where the text cannot be altered at all because of copyright. In Shakespeare, everything is up for interpretation, so each production can truly be different and provide a unique experience to the audience. There just isn’t just one way to do Shakespeare. It’s so plastic, it’s so pliable. And it’s the text that keeps on giving… Despite being written more than 400 years ago. And besides, Shakespeare is long dead, so I don’t have to worry about talking to the author. I can do whatever I want with the text and somebody’s going to watch it and enjoy it and they’ll let me know what worked or what didn’t work. And the next time I do it, I can change it based on that feedback.

19th Century Melodrama (Dion Boucicault, the Corsican Brothers)

Contemporary Black Theatre (Amiri Baraka, Black Arts Repertory Theatre, August Wilson, American Century Cycle)

French Neoclassicism and the Rise of Romanticism (Pierre Corneille, Moliere, neoclassicism)

Greeks (Dithyrambs, tragedy, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripedes, protagonist, deuteragonist, tritagonist, theatron, orchestra, skene, paraskene, masks.)

Medieval (liturgical drama, Hroswitha, platea, mansions, Mystery Cycles, Morality plays, Master of Secrets, Mummers plays)

Modern Theatre (Bert Wiliams, George Walker, In Dahomey, The Harlem Renaissance, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Tennessee Williams, Arthur Miller)

Realism (Henrik Ibsen, modern realistic drama, Anton Chekov, George Bernard Shaw)

Renaissance (Teatro Olimpico, Teatro Farnese, commedia dell’arte, The Theatre, groundlings, autos sacramentales, Comedias Nuevas, corrales, Miguel de Cervantes, Lope de Vega, Pedro Calderon de la Barca)

Restoration Theatre (Elizabeth Barry, Anne Bracegirdle, Mrs. Aphra Behn, Wm. Congreve, Wm. Wycherly, Oliver Goldsmith)

Romans (fabula palliata, scaenae frons, closet dramas, De Architectura)

1 Aristotle,The Poetics of Aristotle, trans. S. H. Butcher, (London, Macmillan and Company, Ltd., 1922) part VI.

2 Ferris-Hill, Jennifer. Horace’s Ars Poetica FAMILY, FRIENDSHIP, AND THE ART OF LIVING. 1 ed., Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2019.

3 “mumming play | drama | Britannica.” Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/art/mumming-play. Accessed 16 July 2022.

4 Creator: Edmund TylneyTitle: Accounts etc. Parts 13 to 33: Part 13 is the account of Edmund Tylney for the year 1 November 1604 to 31 October 1605, appending a list of plays performed at Court which includes seven by Shakespeare.Date: 1604-1605Repository: The National Archives, Kew, UK

5 “In Dahomey”, London – 1903 – Jeffrey Green. Historian.” Jeffrey Green. Historian, https://jeffreygreen.co.uk/in-dahomey-london-1903/. Accessed 18 July 2022

6 Jackson R. Breyer and Mary c. Hartig, Conversations with August Wilson, Jackson, University Press of Mississippi, 2006, p.109.

7 Shakespeare’s theatre company was originally called The Lord Chamberlain’s Men – after Lord Chamberlain, who was their sponsor. Then in 1603, when King James I ascended the throne and became Shakespeare’s patron, the company’s name changed into The King’s Men.

8 The First Folio was the first antology of Shakespeare’s plays, published by his company after the author’s death, in 1623. The Folio has been arranged and edited in the year 2000 by Neil Freeman.

9 Adren Shakespeare and Folger Shakespeare are two popular collections of edited Shakespeare’s works.

10 Shakespeare never published any of his plays during his lifetime to avoid making his work available to other companies of the time.

11 The Globe Playhouse was Shakespeare’s theatre and it featured a round ground plan, with the stage extending into the audience in the form of a thrust stage. A roof only covered the stage area, while the audience stood in an open “courtyard”. A reproduction of the Globe theatre has been built in London and it houses Shakespeare’s productions all year round. There is also a reproduction of the Globe in the USA, at the American Shakespeare Center in Staunton, VA.

12 During Shakespeare’s time, women were not allowed to act on stage, therefore women’s roles were played by men, who were trained to do so from a young age.

13 During Shakespeare’s time, performances happened during the daytime and there was artificial lighting, so there was no way to isolate the stage from the audience.

14 Juliet’s father.

15 Play-on is a term that refers to versions of Shakespeare’s plays that have been translated in modern English, and edited.

16 The Iambic Pentameter, which is the meter Shakespeare used when writing in verse, has a specific rhythm that dictates the way you speak the line.

17 Suzuki and Viewpoints are two acting techniques based on highly complex movement patterns.

18 The play is misogynistic approach to marriage.