1.3: Theatrical Spaces

- Page ID

- 187838

This chapter will introduce you to the physical space “where it happens,” just to quote the famous musical Hamilton.

A Little History

Western theatre is said to have originated in Ancient Greece around 700 B.C.—a long, long time ago. The Greeks considered theatre an extremely valuable part of their lives as citizens and members of the community. Theatrical activities were tied to the cult of the god Dionysus and theatres were located near the temple honoring him. The term “theatre” itself comes from the Greek “theatron”, which means “a place of seeing.”

The Greeks preferred to use the natural disposition and geography of the land when building. For example, the acropolis1—the sacred part of town housing all the temples—was located on top of a hill, overlooking the valley and the sea. That gave them the advantage of seeing an approaching enemy and gave them time to prepare the defense. Since the theatre was a temple (the temple of Dionysus), it was likewise situated on the top of the hill. The theatre’s construction utilized the downward slope of the hill—called koilon—as the seating area for the audience. At the bottom of the hill, there would be a round paved area called the orchestra, which was where the dancers would perform. In the middle of the orchestra, there would be an altar where they sacrificed a goat, marking the beginning of the rituals and of the theatrical activity. Behind the orchestra was the stage and a small, fairly simple building with three doors called the skene. The door at the center was bigger, while the two side doors were smaller. Each door would have a specific meaning; for example, the central door would be the one utilized by the king, or the main characters. The side doors were for messengers, or secondary characters coming from outside the city. The roof of the skene was flat and allowed actors to use it as an upper level, mostly representing the appearances of the gods.

Very little remains of the classic Greek theatre buildings, as most of them have evolved in time, and others were ransacked or destroyed. All we know comes from drawings of Roman scholars, such as Vitruvius. Information about the use of masks and props comes from parts of the Onomasticon, written by Greek scholar Pollux around 170 A.D.

These sources illustrate a few theatrical machineries as well, such as a trap door, allowing the actors to appear and disappear from the roof of the skene. This was utilized as a “special effect,” or Deus-Ex-Machina (literally: “God out of the machine”). In Sophocles’ Medea, the title character flies away on the chariot of the sun at the end of the play. While the exact way this was achieved is far from being clear, it is likely that it happened from the top of the skene. Other theatrical machinery included the periaktoi, triangular prisms with different decorations on each side that could rotate and provide a new design frame for the scene, and the enkiklema, a platform on wheels that could jet out on stage from the central door of the skene.

Differently from the Greeks, the Romans’ main structural element was the arch and its extension in space, generating the vault. This is one of the strongest and most durable building structures, and in fact, many Roman buildings still stand despite the test of time and the impact of many wars. (The Romans also invented concrete, another durable construction element). The arch structure allowed the Romans to build upwards rather than sideways and their buildings tend to be much taller and with several more floors compared to the Greek ones. This is also true when it comes to the theatre structure, which was built up as a fully enclosed space, with the audience accessing the many levels through stairs and tunnels. The stage area and its building became more of a monumental space.

Take a moment to compare the elevation of the architecture of the Greek and Roman theatres depicted in the photos of this chapter.

Later on in history, during the Renaissance, we see the rise of new theatrical spaces such as the Elizabethan Theatre—Shakespeare’s theatre—and the Olympic Theatre in Vicenza, Italy.

The Elizabethan theatre was a polyhedric building, mostly made of wood, that featured a wide circular and uncovered courtyard where the audience would stand. The stage jutted into the courtyard and would be covered with a wooden roof. There would be one or two levels of balconies for those audience members who preferred to sit (and paid a pricier ticket for it).

It was not unusual for Elizabethan theatres to burn to the ground, as they were mostly made of wood and straw and they used torches with open flames for lighting purposes.

All public Elizabethan theatres in London were outside city limits—on the left side of the River Thames—because theatrical activities were illegal in town at the time. Theatres were also usually located close to pubs, if not attached to one. It was normal for audience members to walk in and out of a performance to fetch a beer or something to eat. Talking during performances was also common, and that is why so many plays of the time (Shakespeare’s included) were so long and featured so much repetition: they needed to make sure that the audience wouldn’t miss important information so they repeated it several times.

The modern Globe Theatre in London is an example of an Elizabethan theatre. It was designed and built according to historical documents, although it meets today’s safety standards and features all the necessary modern technology.

In the U.S., there are a couple of reconstructions of Elizabethan theatre. One is the Rose Theatre in Michigan. The American Shakespeare Center in Virginia features a reproduction of the Blackfriars Theatre, which was a private theatrical space of the same age.

The Olympic Theatre in Vicenza was designed by the world-famous Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio in 1580. The building was completed with painted fixed scenery by Vincenzo Scamozzi in 1585, after Palladio’s death. It was inaugurated on March 3, 1585, with a production of Sophocles’ Oedipus The King.

This theatre is known as the oldest covered theatre still in existence. The building has clear references to Classic architecture in style and features exquisite painted panels on stage, giving the illusion of greater depth. The painting technique provides perspective and functions as a Trompe-l’Oeil.

A Trompe l’Oeil, translated literally from the French as “trick the eye” is a large scale drawing that is conceived and realized to provide the illusion of a space that isn’t actually there. It works by using perspective, a drawing technique that succeeds at faking depth on a two-dimensional surface.

Site-Specific or Environmental Theatre

We mentioned in Chapter 1 that in order to have theatre all you really need is an actor telling a story and an audience listening to it. Clearly, the actor and the audience occupy a space.

Sometimes the space they occupy might be on the same level (with no stage). Think about street theatre: you have probably seen a performer, like a mime or a clown, working on the streets amongst groups of passersby. New York has several of them working in Times Square, for example. Performers, or producers, can find a place to use in a theatrical way. Sometimes those places are what we call “found spaces,” such as streets, squares, or urban environments.

Sometimes, however, the actor and audience might be utilizing spaces that were originally conceived for a non-theatrical function and have been converted to performance spaces. We call theatrical performances that use those kinds of spaces site-specific theatre or environmental theatre. Think of all of the “Shakespeare in the Park” festivals that happen all around the U.S. in the summer! Their theatre spaces are parks, which they adapt to facilitate theatrical productions.

Environmental theatre has become quite popular in recent years, partly because of the large number of abandoned spaces and buildings that could use repurposing in large cities around the world.

A great example of a site-specific theatre is the McKittrick Hotel in New York. The building was completed in 1939 as a luxurious five-star hotel. Yet, the hotel had a very short history, as the building was soon condemned and then abandoned. In 2011, two theatre companies teamed up and re-opened it as the location for the site-specific production of Sleep No More, a show loosely based on Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Since then, the building has been hosting theatrical productions and other performative events. In Sleep No More, the audience is let into the building in batches, they are given a white mask and are instructed about how to navigate the production. When they start their experience, the audience can go anywhere they like in the building and follow the performers they prefer. The white masks distinguish the audience from the performers. The building has several floors, and all the rooms are accessible to the audience and to the performers. At times, the performers call for audience participation. All the action is based on movement, and no text is ever spoken, making the experience available for a large audience. Eventually, all the performers converge in a large banquet hall, which is where the show comes to its spectacular conclusion. In a show like this, the audience is entitled to “build” their own experience and theatrical narrative. You can attend such a show many times and have a different experience every time.

Chicago offers another good example of site-specific theatre in the U.S. Right in the middle of the Magnificent Mile, the old 1869 Water Tower has become the home of the Lookingglass Theatre Company. The building had to be renovated and brought back up to code to allow it to be open to the public and support theatrical activities, but the iconic look and original features of the architecture have been preserved, with the theatre company working around—or with—the space in their productions.

In Europe, site-specific theatre often happens in the archaeological remains of ancient Greek and Roman structures or Medieval complexes. For example, in the Sicilian town of Siracusa, Italy, during the months of May and June, the 5th century Greek theatre becomes the stage for an important classic theatre festival, which produces two classic Greek tragedies and one classic Greek comedy.

In Verona, the famous Arena is utilized for concerts and operas during the summer. The image below shows a production of Giuseppe Verdi’s opera Aida at the Arena.

The Festival di Valle Christi takes place in the archaeological remains of a Medieval Gothic Monastery, in Rapallo (Italy), during the summer. This is another example of environmental or site-specific theatre.

Spaces Designed for Theatre

It is time now to discuss structures that were originally conceived and built as theatrical spaces.

The Proscenium Stage

The most popular theatrical space is probably the proscenium theatre. If you have ever been to the theatre in your life, the odds of your being in a proscenium-style theatre are quite high. In a proscenium theatre, the stage directly faces the audience. As the building is conceived exclusively for theatrical performances, there is a distinct division between the spaces that are accessible to the audience from the spaces that serve the production itself.

The audience enters the building, and usually, there is a lobby with a ticket office, a cloak room of some sort, restrooms, and at times a cafeteria or a bar. The lobby gives access to the house, which can be arranged in several ways. You can have a main floor with seats arranged in rows right in front of the stage, and then you can have several other levels, like a Mezzanine and a Balcony, that can be accessed with stairs from the lobby. Usually, Mezzanine and Balcony tickets tend to be cheaper than the main floor (the stalls).

Elements of Proscenium Theatre

When it comes to the space dedicated to performances, the proscenium theatre highlights the division between actors and the audience. The stage is framed with a proscenium arch that creates the window, or frame, through which the audience experiences the production. That frame generates what is also known as the fourth wall. When we talk about actors “breaking the fourth wall”, we mean that during the production the actors directly address the audience, breaking the illusion of separation between what is happening on stage and the “real” world.

Above the stage, there is a fly loft, which is a technical space that allows scenery and lights to be lifted in and out of the sight of the audience. In modern theatres, everything can be motorized so that if a backdrop needs to be lifted, all they need to do is to push a button. Other times theatres still have the traditional mechanic fly system, where all lifts need to be manually operated.

Wing space is available on both sides of the stage to give the actors multiple ways of entering and exiting the stage and, once again, to allow scenery to be moved out of the way. Ideally, the wings should provide a space as wide as half of the length of the stage, while the fly loft should be twice as tall as the proscenium arch to allow backdrops to fly out without any folding.

In order to facilitate the visibility of the performance for the audience, the stage in a proscenium theatre is usually slightly raked (sloped). The audience space is also raked, which allows seats in rows further away from the stage to have less obstructed views.

Other technical spaces in a proscenium theatre include a Green Room, which is a space close to the stage but isolated from it, where the actors can gather in between scenes (and yes, most of the time the Green Room is painted green). Actors also need dressing rooms, which are generally located backstage on lower levels. Some theatres have laundry rooms, as well as a costume and a scene shop.

A very important technical space is the booth, which is where the stage manager and other technicians stay during a performance to operate the technical elements and run the show. Because of the nature of what needs to be done, the booth must have a clear view of the stage. Nowadays, this can be achieved by way of video cameras if needed, although it is still quite common to see the booth at the back of the theatre, or stationed in one of the audience booths.

Italian-Style Theatre

A particular form of proscenium theatre features several booths surrounding the main floor at different levels. This kind of theatre space tends to be very ornate and opulent, and it is also called Italian-style theatre, as it was designed in Italy during the Renaissance. Most Broadway theatres fall into this category.

These buildings were conceived to accommodate the needs of a production and to provide spectacle by way of using machinery that allowed seamless scene changes. They clearly separated the audience from the stage and had comfortable and varied seating for the audience: booths for the wealthier, stalls for the middle class, and a standing balcony area for the commoners. Most cities in Europe had at least one of these theatres. The seating capabilities, the richness of the decor, and the dimensions of the stage soon became elements that not only spoke of the relevance of the theatre itself, but also of the power and status of the city. The theatre soon became a place to be seen, aside from a place to go see something.

Many theatres sold theatre booths to private citizens, and it was up to the buyer to furnish it, within some restrictions in style. Soon enough booths started being used for purposes other than attending a production. They became improvised offices, places for secret encounters or love affairs. They even had curtains to close them completely off from the rest of the house!

Later in the 20th century, when so many left Europe to pursue a new feature in North or South America, a lot of those booths were left behind, with no trace of their owners. This has become a problem since as theatres needed renovations, nothing could be done without the full consent of all the owners. That has halted many theatres in Europe, and in Italy in particular, from staying up to code and keeping their doors open. After a certain amount of time and effort to find the owners, booths could be dispossessed, but the process isn’t easy.

While Italian-style theatres originally accommodated opera performances, nowadays they often are used for musicals. In order to efficiently do so, it needs a space for the orchestra which is usually located below the stage, between the proscenium arch and the audience. We call that space the orchestra pit.

The invention of the orchestra pit is attributed to the German composer Richard Wagner, who had the first theatre with it built in his hometown of Beyreuth. What led Wagner to conceive the orchestra pit was the intention of fully separating the magic of the performance from what made it happen. Basically, he didn’t want the audience to see the musicians as he wanted the music to “magically” support the action on stage. Also, lowering the orchestra from the stage and distancing it from the performers diminished the competition between the actors’ voices and the music coming from the instruments.

The orchestra pit is only utilized when needed, therefore during straight plays, it is usually covered and becomes extra playing space for the actors. The part of the stage extending out of the proscenium arch towards the audience (the covered orchestra pit) is called the apron.

Theatrical Complexes

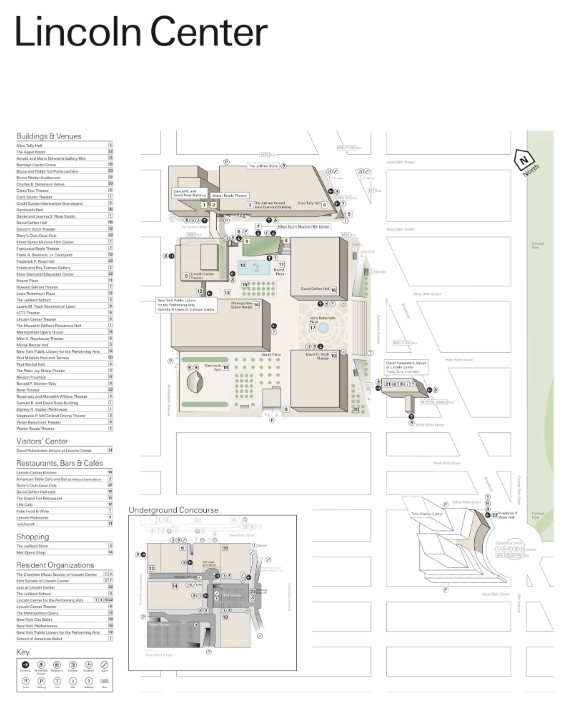

When we think of massive theatre complexes, such as the National Theatre in London or the Lincoln Center in New York, we can see how these structures have been conceived to accommodate all possible needs coming from performances and therefore have several dedicated spaces beyond the actual playhouse.

The Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, for example, includes the Metropolitan Opera House (a 3,900-seat proscenium theatre), a 2,738-seat symphony hall, the David Koch theatre (a 2,586-seat proscenium theatre), the Vivian Beaumont Theatre (a 1,090-seat theatre), the Mitzi E. Newhouse Theatre (a smaller 299-seat theatre), the Clark Studio Theatre (a 120-seat dance theatre), several movie theatres, the New York City Library for the Performing Arts, several rehearsal spaces, and the Julliard School for the Performing Arts.

The Thrust Stage

Another theatrical space that is very popular is the thrust stage. For the most part, thrust stage theatres call for more intimate and less technically demanding design-heavy productions. They also tend to be smaller venues, with fewer seats in the house.

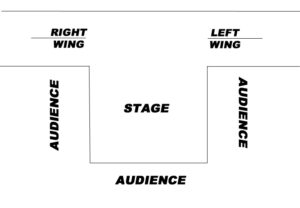

In a thrust theatre, the stage extends itself into the audience, so if an actor is standing in the middle of the stage, the audience is sitting on the actor’s right and left sides as well as in front.

Acting on a thrust stage requires different abilities of the actors. In a proscenium stage, the actors need to keep in mind that the audience is facing them, so unless they intentionally turn their backs to the audience, they can maintain an unobstructed view of the audience, and vice versa. In a thrust stage, with the audience arranged on three sides of the stage, there will be times when the actors have their backs to the audience. It simply cannot be avoided. In order to minimize this issue, the director and the actors have to “block” the show in a more dynamic way. The entrances and exits of the actors can happen from the back of the theatre or directly from the aisles of the audience seating.

A thrust stage also doesn’t allow much of a fourth wall, as there is no proscenium arch and no fly loft. The same can be said for the technical spaces, which are usually in sight so the audience can be aware of what is making everything happen. In short, while on a proscenium stage it is possible to create a complete illusion of a different reality—hiding all the technical elements of a production and letting the audience only see what is happening on stage—the thrust stage shows the production in all of its elements, including the technical ones.

These theatres do not have an orchestra pit, so in case of need, the orchestra must be accommodated either on stage or someplace else off stage. As for the other technical spaces, such as dressing rooms, the green room, and wing space, they are still present in thrust theatres along with the areas dedicated to the audience (restrooms, lobby, ticket office, etc.).

Historically, the Elizabethan theatre is a thrust stage. Shakespeare’s own theatre, The Globe, well represents this kind of space. The building was somewhat circular in its ground plan, with a structure that functioned as the backstage area on one side and a wooden stage extending from it into an un-roofed courtyard, where the audience would stand; this was called the orchestra. All around the orchestra, there were two levels of balconies with wooden seats. Those seats were more expensive since there was a roof on top of them!

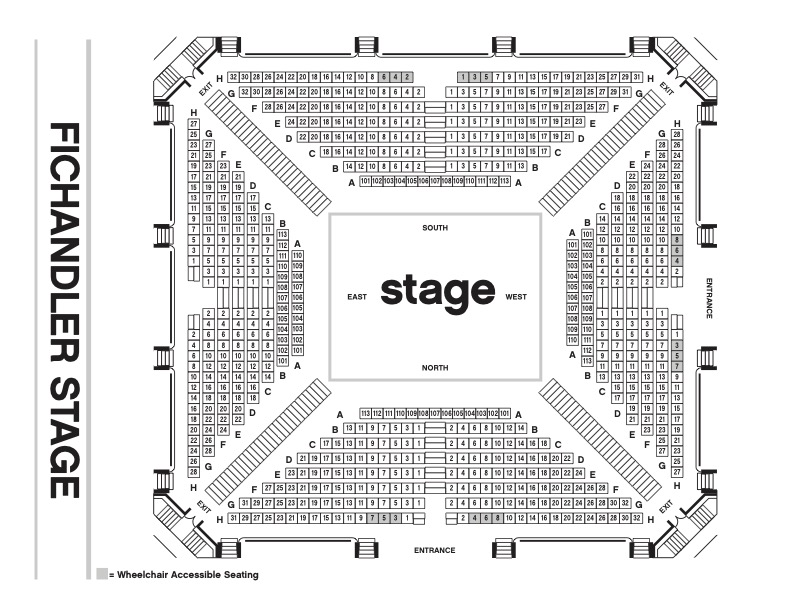

The Arena Stage, or Theatre-In-The-Round

The third kind of theatrical space is the theatre-in-the-round, or arena-style theatre. In this case, the stage is in the middle of the house, with the audience surrounding it on all sides.

The origins of this kind of space date way back in history and speak of theatre’s past just as much as of other events. If we take a quick look at the Romans, we learn how ingenious architects and urban planners they were. Everywhere in Europe, Asia Minor, and North Africa, we find remnants of Roman bridges, roads, aqueducts, and all sorts of buildings, including theatres and amphitheaters. Many of these structures are still perfectly functional today—bridges and roads in particular—while buildings have undergone sometimes massive reconfigurations and renovations, or have been stripped of their parts and material during the Middle Ages (mostly to build churches).

One of the most famous Roman buildings of all time that still stands today is the Colosseum, which is the perfect example of an amphitheater2, or theatre-in-the-round. The Colosseum was built in 80 A.D. under the supervision of Emperor Tito Flavio Vespasiano. It is estimated to have had an audience capacity of anywhere between 50,000 and 70,000 people, which would be sitting or standing in the five different levels of stalls. The action, mostly “games,” would happen in the arena and usually entailed fights between gladiators, races with horses or chariots, fights between men and wild animals, and naumachiae (fights between boats). The entire arena could be transformed into an enclosed pond. As you can see, the Colosseum itself was never conceived or utilized as a theatrical space. Romans had specific theatre buildings as well, although the kind of theatrical performances they produced didn’t really require much of a dedicated space. What was most important for the Romans was the grandeur via the opulent look of the architecture. That was how they impressed the people they colonized and showcased their power.

In modern days, the arena stage has become a theatrical space. It is considered the most challenging space by actors, directors, and designers alike—mostly because everything really happens in plain sight. There is no way of hiding anything or of getting something—or someone—on and off stage without passing through the audience or without the audience seeing it. This kind of stage doesn’t really allow big scene changes or even big pieces of scenery, as they would inevitably block some considerable part of the audience from seeing the action. Acting-wise, the arena calls for an even more dynamic staging on the part of the actors and the director, as this is another space where actors would be at any point giving their backs to some section of the audience. The theatre-in-the-round is utilized most successfully for small, intimate productions or for shows that rely on dialogue rather than spectacle.

The Black Box Theatre

Finally, let’s talk about the Black Box Theatre. This space is the smallest theatrical space, but is the most flexible of all. The Black Box is usually a wide-open rectangular space that is painted black and is fully equipped to function with every possible configuration of audience seating and stage. A Black Box theatre can be arranged as a proscenium theatre, a thrust theatre, an arena, or many other configurations, according to the needs of the production. Similarly to the two previous theatrical spaces, the Black Box does not allow the technical elements to be concealed from the audience’s view, and given the size of the space itself, it is best utilized when producing small, intimate shows. This space allows close proximity between the actors and the audience, creating a very unique experience. Many theatres around the country have a Black Box Theatre alongside a bigger venue or main stage. At times, the Black Box is utilized as a rehearsal space or dedicated space for staged readings and smaller productions. Universities, for example, tend to have two theatrical spaces, one of them being a Black Box.

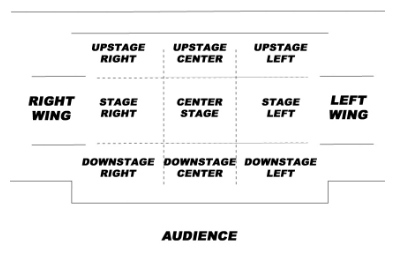

Blocking and Stage Positions

Blocking is all of the planned movement and positions of the actors on stage during a performance. The blocking depends on the script, the stage configuration, and on the artistic decisions of both the actors and the director.

When discussing stage positions on a proscenium or a thrust stage, the following convention is adopted: imagine an actor standing center stage, his back to the back of the stage, facing the audience. If we want the actor to come closer to the audience, we tell the actor to come downstage. If we want the actor to be further away from the audience, we tell him to walk upstage. Left and right are determined according to the position of the actor, who is facing the audience and has his back to the back of the theatre. If we tell the actor to cross Downstage Right, the actor will walk downstage (towards the audience) and to his right.

If we are in an arena stage, it is up to the director and the actors to agree on where is upstage. When that is determined, blocking goes from there.

Antagonist

Apron

Arena Stage

Aristotle and his elements of script analysis

Black Box

Blocking and blocking positions

Booth

Elizabethan Theatre

Fourth Wall

Globe Theatre

Green Room

Italian-style Theatre

Koilon

Mechanic Fly System

Olympic Theatre

Orchestra Pit

Proscenium Stage (with its elements)

Proscenium Arch

Site Specific/Environmental Theatre

Skene

Theatron

Thrust Stage

Wing Space

1 Acropolis, from Greek : High City.

2 The term “amphitheater” comes from Latin. With “amphi” meaning double, and amphitheater doubles the size of the “regular” theatre stage, making it circular instead of semi-circular.