2.2: Evaluation of information- standard approaches, at the sentence level, confirmation bias

- Page ID

- 65076

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

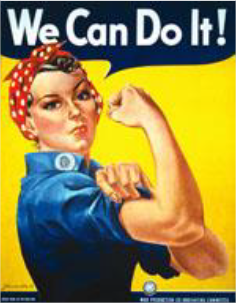

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)My Uncle John was a good source of information on how to make chili and I could ask Aunt Margaret about what it was like to be a Rosie the Riveter (women who left their traditional roles in World War II to work in factories building aircraft and other war machines). But, if we wanted to find the nutritional value of chili, or maybe how food and culture in the southwest influenced each other, we might need a book or an article. If we wanted to delve into cross cultural patterns of contributions by women to the war effort in World War II, we would need more than Aunt Margaret’s memories.

Standard Approaches

We saw in Section 2A that we need to understand the kind of information we need to determine if we need an article, book or blog. But the why of doing research will also determine the resources you use. Ask yourself, “Why am I doing research? What am I going to do with this information?” Answers could include: write an academic paper, see who wins a bet or get family history straight so it can be passed on. In this section we are asking, “Is the information good enough for how you will be using it?” If you are writing an academic paper on women’s contributions in WWII, you will need more than an interview with Aunt Margaret. You will need scholarly and/or peer reviewed sources.

Before you get into looking at the list below, what criteria would you use to determine if something would be acceptable to use in an academic paper? What would your professors expect to see? You probably can create a list very similar to what you will read below. Read it anyway, because the whole purpose of this book is to bring together in one place all the bits and pieces that go into good research. You don’t want to miss any of the best bits!

What you are going to do with the information will determine how credible the information needs to be. If Grandma tells you to eat your greens because they are good for you, that should be good enough and you ought to eat them! If you want to write a college paper on why greens should be part of a healthy diet, you are going to need credible, peer reviewed, scholarly sources of information.

When writing a college paper, you will need credible information. You will look for scholarly books and peer-reviewed journal articles written by experts on your topic (See 2D for deeper look at scholarly and peer-reviewed resources). Perhaps there is a university professor who is highly regarded in the field of Balkan folk dancing. Imagine that professor writing an article on the importance of eating green vegetables. Is that professor an expert in the field? Would that article be peer reviewed? Would that be a good one to use for a paper about the nutritional value of greens? No, no and nope. But articles about Balkan folk dancing written by said professor would be perfect for a college paper on Balkan daily life and culture.

Here is what University of California, Los Angeles (n.d.) asks of their students:

When evaluating a resource for credibility and appropriateness consider these questions:

- Who is the author(s)?

- When was the source published? How current is the information?

- Is the information directly applicable to the situation at hand?

- If not, how close is it to the current situation?

- What underlying assumptions have been made in the data?

- Is there any reason to suspect bias of any sort in this data source?

- How good is the evidence given by (or cited) in the source?

- Is there any potential conflict of interest?

- Is any significant data omitted?

- Are there any other data sources which should be consulted?

- Are there conflicting potential causes for the event?

- Are there any fallacies in the reasoning?

- What reasonable conclusions are possible?

Another standard way to evaluate information is the C.R.A.A.P. test (Blakeslee, n.d.). Its easy to remember acronym, along with its usefulness, makes this test popular.

| C | Currency | Ask how current the information needs to be? If doing a study on DNA testing, you want to be sure you have current information. If, however, you are studying the impact of Lincoln’s speeches through time, you still want current research, but you may also need research done over the last 150 years. |

| R | Relevance | Not only is the information on your topic, but does it answer some of your questions? Is it meaty enough? |

| A | Authority | Who is the publisher? A recognized professional organization or publisher in the field? Who is the author? An expert in the field? Is this expert writing about what s/he is an expert in or has s/he strayed into unfamiliar waters? For example, is a surgeon writing about school reform? |

| A | Accuracy | Does the information have an internal logic or do the authors make cognitive leaps? For example, the authors might write that they found 80 % of college students eat vegetables every day and conclude that at least half of college students must be vegetarian. What? No, that does not follow logically. Another needed accuracy check is how does the information complement or contradict other information from other credible sources? Before we believe that the moon is made of cheese because a credible looking source says so, we would want to ask, what do other credible sources say? |

| P | Purpose | Purpose is about bias and intent. Some things are written specifically to get us to believe one thing over another (think politics) or to buy a specific product (think infomercial, or any ad campaign). Journalists and academics do everything in their power to minimize bias through professional ethics and by using the peer review process. (See 2D for more on peer review.) |

At the Sentence level

So far we have discussed evaluating a resource by considering the publisher, the authors and so forth. We want to ask questions such as does this information fit with other information on the topic or is it very different? Is the information logical and does it make sense? Are statements made as fact actually opinion? We should also evaluate the resource at the sentence level. This means we need to use critical thinking as we read, not just when choosing what we read.

Consider this statement:

4 out of 5 dentists recommend Staybright toothpaste.

What information is missing from this statement that is needed to make it truly valuable and usable? You might ask, “Were all the dentists in the world surveyed? How many need to be surveyed to provide statistically significant results? When was this survey taken? Where was this survey taken?” What would you insist the speaker tell you to make the statements clear, complete and useful? A clearer more complete statement would be:

Four out of five dentists from Iceland randomly surveyed in a 2017 study recommend Staybright toothpaste.

Think through the following unrelated sentences. What other information would you need from the writer to make the information clear?

- The importation of bananas has risen 18%. Possible answers: Imported to/from where? In what year? 18% of what? All kinds of bananas?

- They support tax reform. Possible answers: Who is “they”? What kind of tax reform (corporate, income, gasoline)?

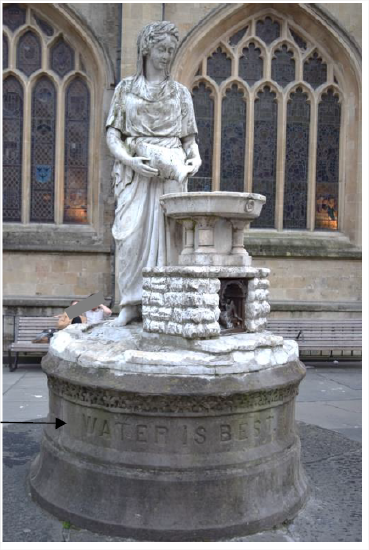

- Water is best. Evaluate. Even if written in stone! Possible answers: What kind of water (tap, spring…)? From where (Italy, Colorado)? Best for what (bathing, agriculture, making smoothies, fighting colds)?

Confirmation bias

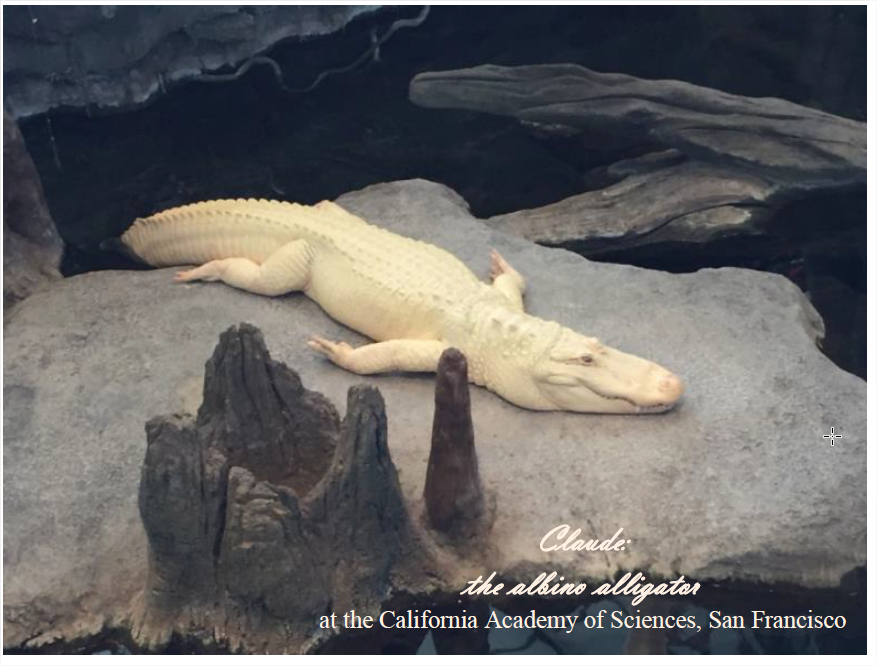

What about statements or concepts we think we “know” are true? What is your birthdate? How do you know that? There is a measure of trust in what we declare as our birthdate. We believe our parents and our birth record. Most likely we can trust our birth record as accurate just as we can trust the highly capable experts at The National Park Service (NPS): a very reliable source for all things flora, fauna and geologic in our nation’s parks. The professional at the NPS are trustworthy experts. According to the NPS, “The color of adult alligators can be olive, brown, gray or nearly black.” This sounds reasonable. But, what about Claude? He resides in the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco.

Claude does not confirm my bias (which was reinforced by the National Park Service) about the color of all alligators. He not only challenged my assumptions, but also made me aware of an assumption I did not know I had. Claude is rather cool about things like that though. Do we (and the National Park Service) need to qualify all our statements with, “To our knowledge the color of alligators is …” or “The common color of alligators are…”?

So Claude teaches us at least three things: 1) It is a good idea to listen critically when statements are made 2) use language carefully so that we communicate what we want and 3) most importantly constantly be on the lookout for assumptions we hold. What other assumptions do I hold? What about you?

According to Hull in his 2017 interview with Leonard, “Confirmation bias is harmful when change is needed, when our traditional ways of knowing and acting do more harm than good. It supports group think, preaching to the choir, and xenophobia. It narrows the window of opportunities and makes one brittle and resistant to change.” On the website of the Center for Leadership and Global Sustainability, Hull (2017) continues his discussion:

People search for and remember facts that confirm their initial beliefs and ignore or forget unsupportive evidence. The explosion of information made accessible by the web makes it easy for people to find the support they crave. The slow, difficult, testable, and transparent scientific method is an institution humans invented to help us overcome the confirmation bias…If confirmation bias wasn’t enough of a threat to experts, expertise, and rationality, then its close cousin, identity protecting reasoning (IPR), is downright frightening... Most people rather doubt science and experts than question their identity or politics…Information of all types has never been easier to find. But the high quality, peer-reviewed, carefully produced arguments and facts tend to be less accessible, often disguised by jargon and hidden behind professional or disciplinary gates. And even if the information generated by experts is found, it is but one click away from half-baked, last minute, advocacy-driven drivel. People inexperienced with a topic have no way to know the difference between science and drivel. It is understandably [sic] that they instead accept the most frequently found, oft repeated arguments that just so happen to confirm their initial beliefs and assumptions.

Leonard’s (2017) interview with Hull continues, “‘The danger with confirmation bias is that it allows us to easily dismiss facts, because there are always alternative facts to confirm a bias,’ says Hull, whose research is focused on helping leaders and organizations achieve more sustainable futures. ‘So if someone presents a counter argument, it is in our nature to dismiss it as fake news.’”

Let us continue this discussion with some other things you need to know to understand information. When deciding whether or not to use an information resource, keep all the bits in this section in mind!