7.4: The Growth and Spread of Early Christianity

- Page ID

- 226338

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The Growth and Spread of Early Christianity

Persecution of Christians

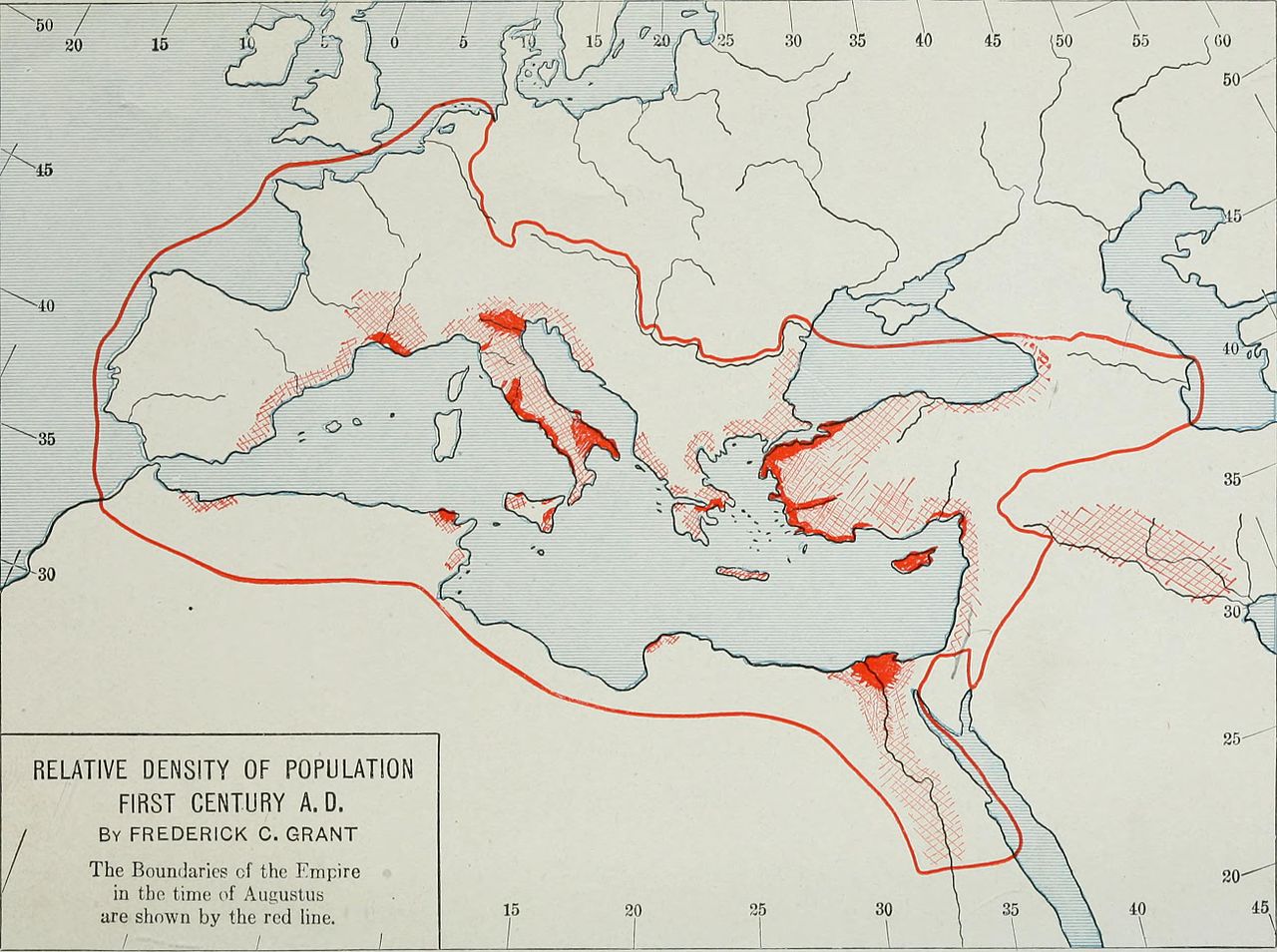

Members of the Early Christian movement often became political targets and scapegoats for the social ills and political tensions of specific rulers and turbulent periods during the first three centuries, CE; however, this persecution was sporadic and rarely Empire-wide. (41)

The first recorded official persecution of Christians on behalf of the Roman Empire was in 64 CE, when, as reported by the Roman historian Tacitus, Emperor Nero blamed Christians for the Great Fire of Rome. According to Church tradition, it was during the reign of Nero that Peter and Paul were martyred in Rome. However, modern historians debate whether the Roman government distinguished between Christians and Jews prior to Nerva’s modification of the Fiscus Judaicus in 96, from which point practicing Jews paid the tax and Christians did not.

The Diocletianic or Great Persecution was the last and most severe persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire, which lasted from 302–311 CE. In 303, the emperors Diocletian, Maximian, Galerius, and Constantius issued a series of edicts rescinding the legal rights of Christians and demanding that they comply with traditional Roman religious practices.

Later edicts targeted the clergy and ordered all inhabitants to sacrifice to the Roman gods (a policy known as universal sacrifice). The persecution varied in intensity across the empire—it was weakest in Gaul and Britain, where only the first edict was applied, and strongest in the Eastern provinces.

During the Great Persecution, Diocletian ordered Christian buildings and the homes of Christians torn down, and their sacred books collected and burned during the Great Persecution. Christians were arrested, tortured, mutilated, burned, starved, and condemned to gladiatorial contests to amuse spectators. The Great Persecution officially ended in April of 311, when Galerius, senior emperor of the Tetrarchy, issued an edict of toleration which granted Christians the right to practice their religion, though it did not restore any property to them. Constantine, Caesar in the western empire, and Licinius, Caesar in the east, also were signatories to the edict of toleration. (42)

Edict of Milan

In 313, Constantine and Licinius announced in the Edict of Milan “ that it was proper that the Christians and all others should have liberty to follow that mode of religion which to each of them appeared best, ” thereby granting tolerance to all religions, including Christianity.

The Edict of Milan went a step further than the earlier Edict of Toleration by Galerius in 311, and returned confiscated Church property. This edict made the empire officially neutral with regard to religious worship; it neither made the traditional religions illegal, nor made Christianity the state religion (as did the later Edict of Thessalonica in 380 CE). The Edict of Milan did, however, raise the stock of Christianity within the empire, and it reaffirmed the importance of religious worship to the welfare of the state. (42)

The Nicene Creed

In 325 CE Constantine invited clerics from across the empire to a conference at Nicaea where he made a plea for unity. (54)Under the supervision of Emperor Constantine I, the Nicene Creed (325 CE) was composed by an ecumenical council , which was and is accepted as authoritative by most Christian groups, but not by the Eastern Orthodox Church (at least, the second version in 381 CE is rejected for adding in the Filioque Clause—”And the Son”).

The Nicene Creed describes the pre-existence of Jesus Christ, his role in the future judgment of humanity, how Jesus is “homoousis” — of the same substance with God, how and why the Holy Spirit is to be worshipped as part of the holy family, discusses the requirement of baptism, and minimizes the earthly ministry of Jesus Christ, interestingly. (41)

The Athanasian Creed

Although there are others, the Athanasian Creed (328 CE) also proved important in pushing back against the heresies of the day, namely Docetism and Arianism . (41)

- Docetism held that Jesus’ humanity was merely an illusion, thus denying the incarnation (Deity becoming human).

- Arianism held that Jesus, while not merely mortal, was not eternally divine and was, therefore, of lesser status than the Father. (44)

Christianity: State Religion of Roman Empire

By the 5th century CE, Christianity had become the state religion of the Roman Empire, leading to a dramatic change in how the faith played out in greater society. This caused a shift in Christianity from private to public worship; from a distinctly Jewish character to one more aligned with the Gentiles; from an individual matter to more of a community affair; from a seeker-driven faith to an exclusively chosen body of believers; from a looser, more informal structure to that of distinct strata of operation and authority; and from gender empowering to more specific gender-specific limitations. Additionally, Christian leaders had to figure out how Christianity integrated with Roman law and government, dealt with barbarian peoples, and still maintained the essence of Jesus’ teachings and missions for his followers. (41)

Christianity in the Early Middle Ages

With the decline and fall of the Roman Empire in the west, the papacy became a political player, first visible in Pope Leo’s diplomatic dealings with Huns and Vandals. The church also entered into a long period of missionary activity and expansion among the various tribes. Catholicism spread among the Germanic peoples, the Celtic and Slavic peoples, the Hungarians, and the Baltic peoples. Christianity has been an important part of the shaping of Western civilization, at least since the 4 th century. (43)

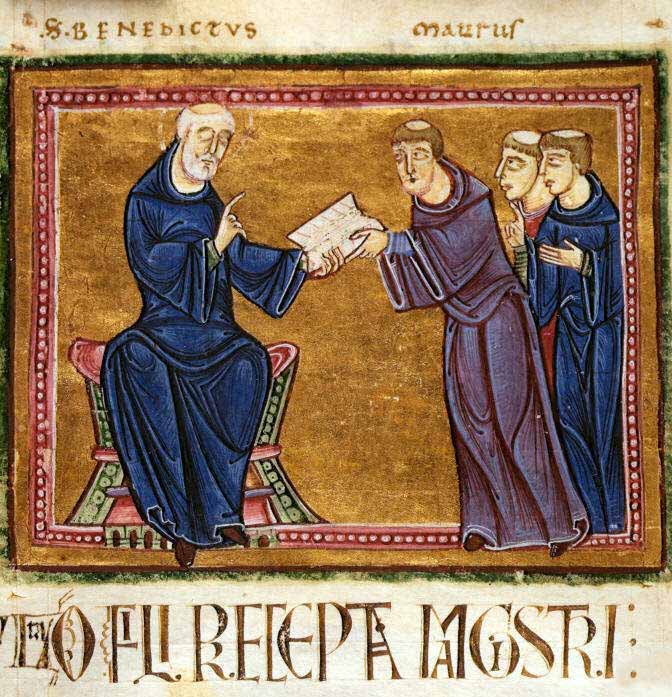

Around 500, St. Benedict set out his Monastic Rule , establishing a system of regulations for the foundation and running of monasteries. Monasticism became a powerful force throughout Europe, and gave rise to many early centers of learning, most famously in Ireland, Scotland and Gaul, contributing to the Carolingian Renaissance of the 9 th century.

In the 7 th century Muslims conquered Syria (including Jerusalem), North Africa and Spain. Part of the Muslims’ success was due to the exhaustion of the Byzantine Empire in its decades long conflict with Persia. Beginning in the 8 th century, with the rise of Carolingian leaders, the papacy began to find greater political support in the Frankish Kingdom.

The Middle Ages brought about major changes within the church. Pope Gregory the Great dramatically reformed ecclesiastical structure and administration. In the early 8 th century, iconoclasm—the destruction of religious icons—became a divisive issue, when it was sponsored by the Byzantine emperors. The Second Ecumenical Council of Nicaea (787) finally pronounced in favor of icons. In the early 10 th century, Western Christian monasticism was further rejuvenated through the leadership of the great Benedictine Monastery of Cluny. (43)

Christianity in the High and Late Middle Ages

In the west, from the 11th century onward, older cathedral schools developed into universities (see University of Oxford, University of Paris, and University of Bologna). The traditional medieval universities — evolved from Catholic and Protestant church schools — then established specialized academic structures for properly educating greater numbers of students as professionals. Prior to the establishment of universities, European higher education took place for hundreds of years in Christian cathedral schools or monastic schools, in which monks and nuns taught classes; evidence of these immediate forerunners of the later university at many places dates back to the 6 th century AD.

Accompanying the rise of the “new towns” throughout Europe, mendicant orders were founded, bringing the consecrated religious life out of the monastery and into the new urban setting. The two principal mendicant movements were theFranciscans and the Dominicans founded by St. Francis and St. Dominic respectively. Both orders made significant contributions to the development of the great universities of Europe. Another new order was the Cistercians , whose large isolated monasteries spearheaded the settlement of former wilderness areas. In this period, church building and ecclesiastical architecture reached new heights, culminating in the orders of Romanesque and Gothic architecture and the building of the great European cathedrals.

The Crusades

From 1095 under the pontificate of Urban II, the Crusades were launched. These were a series of military campaigns in the Holy Land and elsewhere, initiated in response to pleas from the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I for aid against Turkish expansion. The Crusades ultimately failed to stifle Islamic aggression and even contributed to Christian enmity with the sacking of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade.

Over a period stretching from the 7 th to the 13 th century, the Christian Church underwent gradual alienation. This resulted in the Great Schism in 1054, dividing the Church into the so-called Latin or Western Christian branch, the Roman Catholic Church , and an Eastern, largely Greek, branch, the Orthodox Church .

These two churches disagree on a number of administrative, liturgical, and doctrinal issues, most notably papal primacy of jurisdiction. The Second Council of Lyon (1274) and the Council of Florence (1439) attempted to reunite the churches, but in both cases the Eastern Orthodox refused to implement the decisions and the two principal churches remain in schism to the present day. However, the Roman Catholic Church has achieved union with various smaller eastern churches.

Beginning around 1184, following the crusade against the Cathar heresy, various institutions, broadly referred to as theInquisition , were established with the aim of suppressing heresy and securing religious and doctrinal unity within Christianity through conversion and prosecution. (43)

Contributors and Attributions

- Christianity. Authored by: John S. Knox. Located at: https://www.ancient.eu/christianity/. Project: Ancient History Encyclopedia. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Christianity and the Late Roman Empire. Authored by: Lumen. Located at: courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-worldhistory/chapter/christianity-and-the-late-roman-empire/. Project: Boundless World History. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- History of Christianity. Authored by: Wikipedia for Schools. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Christianity. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Christianity. Authored by: Wikipedia for Schools. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Christianity. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike