7.2: Exaggeration and Lying

- Page ID

- 21993

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)A lie is a false statement made with the intent to deceive. What are salespersons doing when they say that "$15,000 is absolutely the best price" they can sell you the car for, and then after ten more minutes of negotiating they drop the price another $500? The statement about the $15,000 was false—just another sales pitch. We consumers are so used to this sort of behavior that we hardly notice that it's an outright lie.

Here is a short ad: "Wiler's Whiskey; it's on everyone's lips." If it is, then you won't be safe driving on any road. But it isn't. The ad's exaggerated claim is literally a lie made to make a mild point, that Wiler's Whiskey is a popular whiskey, one that you should consider drinking yourself if you like whiskey.

People at home, hoping to make some money in their spare time, are often exploited by scams. Scams are systematic techniques of deception. They are also called cons. Here is an example called the craft con. In a magazine ad, a company agrees to sell you instructions and materials for making some specialty items at home, such as baby booties, aprons, table decorations, and so on. You are told you will get paid if your work is up to the company's standards. After you've bought their package deal, knitted a few hundred baby booties, and mailed them, you may be surprised to learn that your work is not up to company standards. No work ever is; the company is only in the business of selling instructions and materials.

What can you do in self-defense? If you are considering buying a product or service from a local person, you can first check with your local Better Business Bureau about the company's reliability. If you have already been victimized, and if the ad came to you through the U.S. mail, you can send the ad plus your story to U.S. postal inspectors. Similar actions apply in other countries.

Here's another example of the craft con. If you have ever written a humorous story, you might be attracted by this advertisement in a daily newspaper:

Mail me your personal funny story and $5—perhaps win $10 if I use. Write Howard, 601 Willow Glen, Apt. 14, Westbury, N.D.

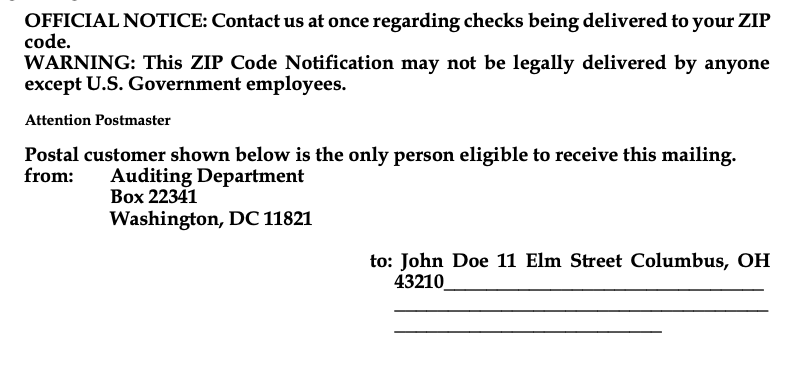

Howard has no intention of your winning $10. Have you ever seen ads suggesting that if you don't buy a certain brand of tire you will be endangering your family? This is a scare tactic, and it is unethical if it exaggerates the danger of not buying those particular tires. Here is a sleazy use of the tactic. It is the cover of an envelope advertising something. Are you a good enough detective enough to spot what it is advertising?

This Is an Important Notification

Regarding Your ZIP Code

So, what are they selling? Did you figure out that this is a perfume ad? You didn’t? You weren't supposed to. The page is supposed to intimidate you—make you fear that your ZIP code is about to change, that checks are being delivered incorrectly, that you are being audited, or that you are about to receive vital government information. When you open their booklet, you find out that everyone in your ZIP code is being offered the chance to buy a new brand of perfume. The sentence "This ZIP Code Notification may not be legally delivered by anyone except U.S. Government employees" merely means that only postal workers may deliver the mail from the post office.

Exaggeration is not always bad. It can be a helpful tactic is catch someone's attention. We readers and viewers, though, need to be alert to its presence and need to figure out whether the tactic is benign or instead dangerous.

This excerpt from a newspaper column contains some exaggeration. Identify where this occurs and who is doing it. Sitagu Sayadaw is one of Myanmar's most revered senior monks. Myanmar is also called "Burma."

Sitagu Sayadaw recently gave a sermon at an army combat training school. He alluded to a historical battle between Buddhists and Tamils. After the battle, the story goes, the Buddhist king was troubled because thousands of Tamils were dead. The monks reassured him, saying that all the Tamils killed amounted to just one and a half human beings, because only those keeping Buddhist precepts were human.

…I drove to a village on the Irrawaddy River to hear Sitagu Sayadaw speak. His sermon was restrained. I got to talking to Daw Kyaing, 65, a woman with a lovely smile. I asked why more women than men were attending.

"Because only the women want to go to heaven. The men are busy drinking."

"Where will the men go?"

"To hell."

"What do you want to be in your next life?"

"I don't want to come back in any form."

"One life is enough?"

"More than enough."

"You wouldn't want to come back as a man?"

"No, I don't want to drink. My husband was violent. We had 11 children. Now he can't drink, so he doesn't beat me anymore. I live with him, and grow rice, on a bend in the peaceful river."

—Roger Cohen, The New York Times, "The Farthest Point of a Burmese Journey," December 2, 2017, p. A23.

- Answer

-

Exaggeration occurs in two places. (1) Shouldn't Buddhist monks' number "one and a half" be changed to "three"? Hmm. OK, maybe not "three. " (2) Saying "only the women want to go to heaven" is an exaggeration because it incorrectly implies that men do not want to go to heaven, but the exaggeration effectively makes Daw Kyaing's point. [The photo is from Iran at drpaulfuller.wordpress.com/2...ms-in-burma/.]