3.4: Cultural Approaches to Rhythm

- Page ID

- 91139

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Western Art Music- downbeat emphasis

In Western Art music the aesthetics for preferred rhythmic emphasis have evolved and devolved for over a millennium. It is important to note that the aesthetics for music of the 20th century were often experimental. Composers like Karlheinz Stockhausen or Igor Stravinsky stretched the rhythmic norms by creating music that was extreme in rhythmic complexity. This is to say that, at the beginning of the 21st century it is hard to imagine music becoming more rhythmically complex. This represents a polar opposite reality from the lack of rhythmic emphasis in Western Art music that is evident in the first 1000 years of Christian practice. Perhaps it was an attempt to keep out pagan practice or it was because the venues for performance were extremely resonant; either way rhythm was not emphasized as much as the other elements in Medieval and Renaissance music.

In the Baroque style period rhythm became more of an emphasis with steady background pulse being felt in a majority of the works. From the Baroque through the Romantic era emphasis was generally placed on the strong beats/downbeats of measures. The downbeat emphasis in Western Art music can be felt on beat one of triple meters and on beats one and three of quadruple meters. In some orchestral genres like waltzes or marches downbeat emphasis is heard played on drums. In other genres, and in contrast to popular music, there is often no instrument dedicated to strictly emphasizing the rhythm of Western Art music.

American/World Pop Music- backbeat emphasis

Since the early 20th century American Popular Music have been influencing world popular music styles. Elements of American pop can now be heard in the pop music of many other cultures. Examples of this are found in Bollywood music, K- pop, J-pop, Russian rock and various African pop styles (amongst others). One of the main elements that can be heard in all of these styles is a backbeat emphasis. The backbeat is beats 2 and 4 of a 4/4 measure. In many contemporary popular genres beats 2 and 4 are actually articulated by the snare drum (or an electronic version of this instrument). The backbeat is also a rhythmic emphasis in older pop genres including the blues and jazz.

Southeast Asian Colotomic Meter

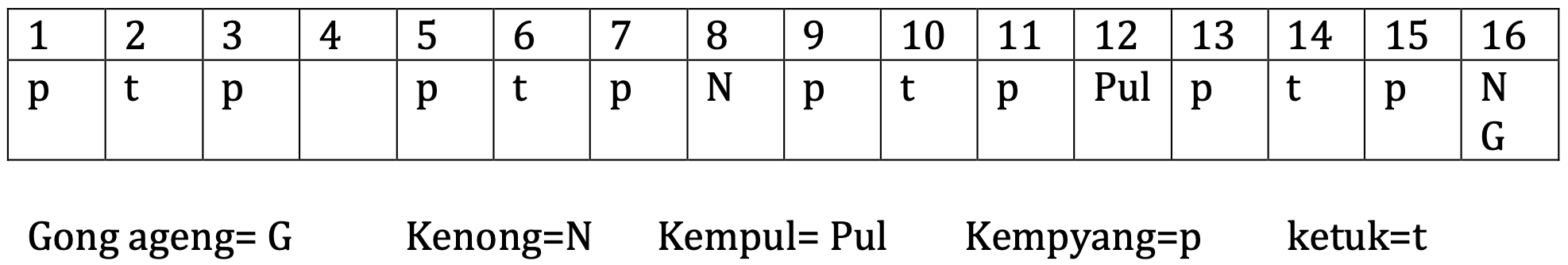

In Thai piphat, Japanese gagaku, and Indonesian gamelan ensembles the concept of colotomic meter is used to indicate the metric foundation of the music. A colotomic meter is a cyclical pattern played by various instruments that reveals the rhythmic structure of the work. In colotomic meters specific instruments play on specific beats to form a rhythmic cycle or the western equivalent of a meter. These instruments are often gongs. In gamelan the higher-pitched generally play at a faster rate than the lower-pitched instruments. This means that the lowest pitched gongs will often mark important beats in a cycle. For instance in the colotomic cycle called ketawang the largest gong only plays on one beat. When this gong is played it indicates the beginning of the piece and each subsequent cycle. In Figure 5 we see that this gong (gong ageng) plays on the 16th beat of the cycle. It is interesting to note that the most important beat is the last beat of the cycle. This is a differing aesthetic to downbeat emphasis. The instrument that splits the 16 beat cycle by playing on beat 8 (and sometimes 16) is called the kenong. This is a gong that is played on its side (not hanging). Beat 12 is performed on a hanging gong called kempul. This gong is not as big as the gong ageng and therefore is higher in pitch. Filling in the rest of the spaces are the kempyang and ketuk. The only beat with a silence is beat four. The other melodic and rhythmic parts happen on top of this foundational pattern.

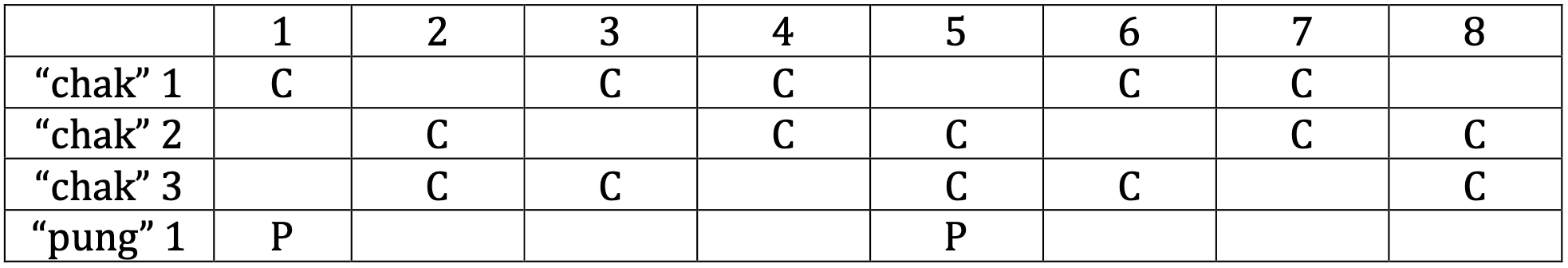

According to Michael Bakan, an ethnomusicologist at Florida State University who specializes in Gamelan music of Indonesia, Kilitan telu is an interlocking rhythmic pattern that forms the basis of many melodies and rhythms in gamelan genres (Bakan, 2012). The main rhythm in kilitan telu is played by three instruments/voice groups that each start on a different beat. This kind of pattern is often heard in a vocal based gamelan style called Ketak. The interlocking of the kitilan telu pattern reflects the interdependence in Indonesian society. A typical Kecak-style exercise using the interlocking kilitan telu rhythm is listed in Figure 6.

Southwest Asia/North African Rhythmic Modes/Iqa'

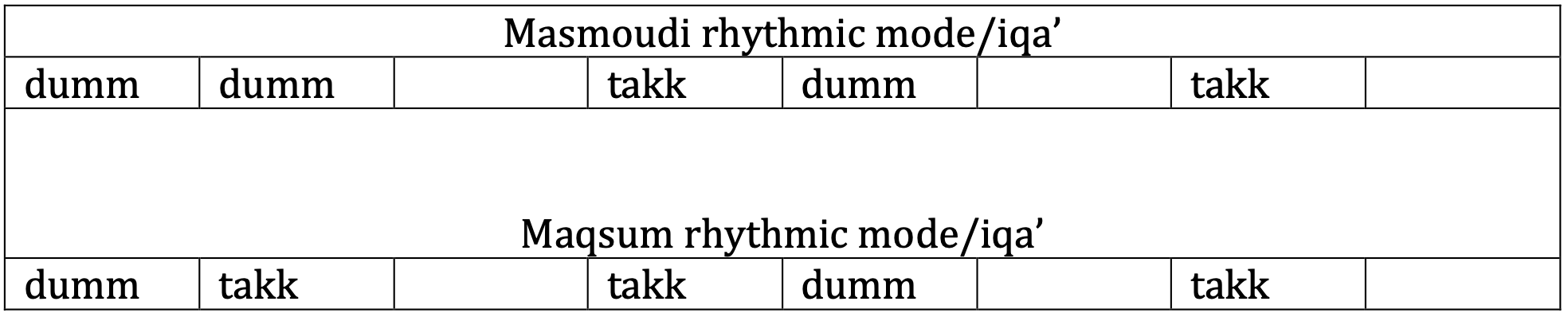

In the region of the world that Westerners have traditionally called the “Middle East” secular music practices are rhythmically anchored by rhythmic modes known as iqa'. There are hundreds of variations of iqa'. Each one has subtle differences that give it particular expressive meaning. The iqa' are referred to as rhythmic modes instead of “meters” because of the expressive capacity of each mode (root word mood). Each iqa' is a particular arrangement of accented and unaccented rhythms. Several iqa' are commonly heard. The most common percussion instruments that play the qi’ are the dumbek (also known as the darabukkah or darbuka), tar and rik. Much like a drum set in Western pop plays in beats, iqa’ consists of low pitch and high pitch sounds played on the dumbek or other instruments. The low sound is called dumm while the high-pitched sound is called takk. Some common iqa’ are diagramed in Figure 7.

Indian Tala

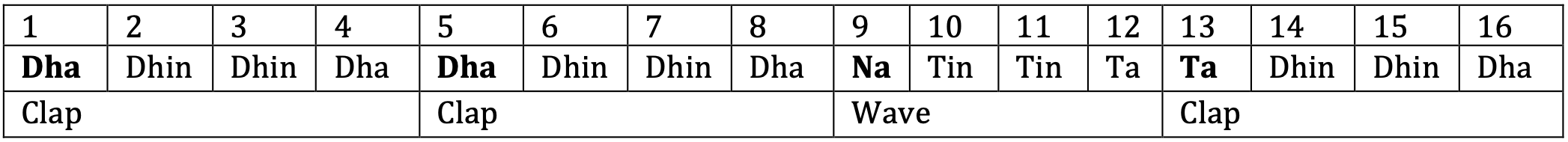

In traditional Indian music the rhythmic foundations are called talas. Tala is

the Indian equivalent of Western meters. Talas are made up of combinations of smaller groupings. Sometimes the end results are very complex talas. Because there are many ways to group beats together there are literally over 100 different talas. This is notable when compared to the primary use of less than ten meters in most Western music. When listening to the tala knowledgeable listeners often mark the parts of the tala by using a series of claps and waves of the hands known as kriyas.

Theka is a vocal pattern that indicates the patterns of a tala. Vocalizing the theka is a common way to learn talas. See Figure 8 for a guide to tintal (a common taal).

In many Hindustani performances there is a form that grows from a calm introduction and slowly builds until it reaches a rapid, and intense, conclusion. These pieces involve much virtuosic performance. Often there will be no tala or pulse in the beginning. At the point that the table (drums) enter there will be a new focus on rhythmic development.

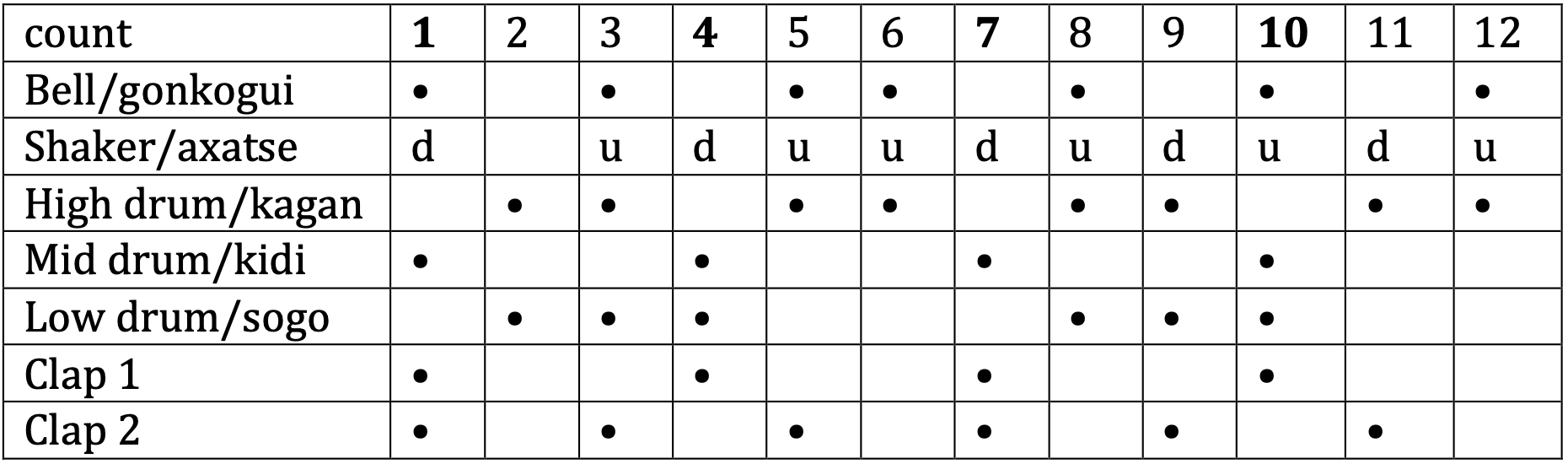

African Polyrhythm

Rhythm is the element of music most commonly associated with African (particularly Sub-Saharan) music. The rhythms of African music accompany activities ranging from day-to-day chores to complex ceremonies. Drumming and dancing are two common forms of African music. As is the case with music that accompanies dance there are often ostinato drumming parts. An ostinato is a repeating pattern or motive. When differing rhythmic ostinatos combine they become a polyrhythm. Simply put a polyrhythm is multiple rhythms performed simultaneously. Polyrhythmic drumming is the musical manifestation of an aesthetic that values separate “small” parts combining to form a greater whole. This can be seen as a musical reflection of cooperation for the better of all (Stone, ?).

A typical dance-drum piece of music from West Africa contains many polyrhythms. They are not conceptualized within a meter but instead are thought of as complementary rhythmic components of one flow. The rhythmic pattern that holds all of the differing ostinatos together can be called a timeline pattern. This pattern is typically played on a metal idiophone (gonkogui=bell). The phrase played on the bell is cycled/repeated and is used to place all of the other drum parts. The other parts are generally fixed with the exception of a master drum. This drum generally leads the ensemble (including dancers) by playing differing patterns that signal the timing of changes. The master drum is generally the only part free to improvise at will. For an example of a polyrhythmic piece see Figure 9. The effect of listening to polyrhytmic music is that tempo and phrase perception can shift between parts dependent upon the vantage point of the listener (Locke, 2010).

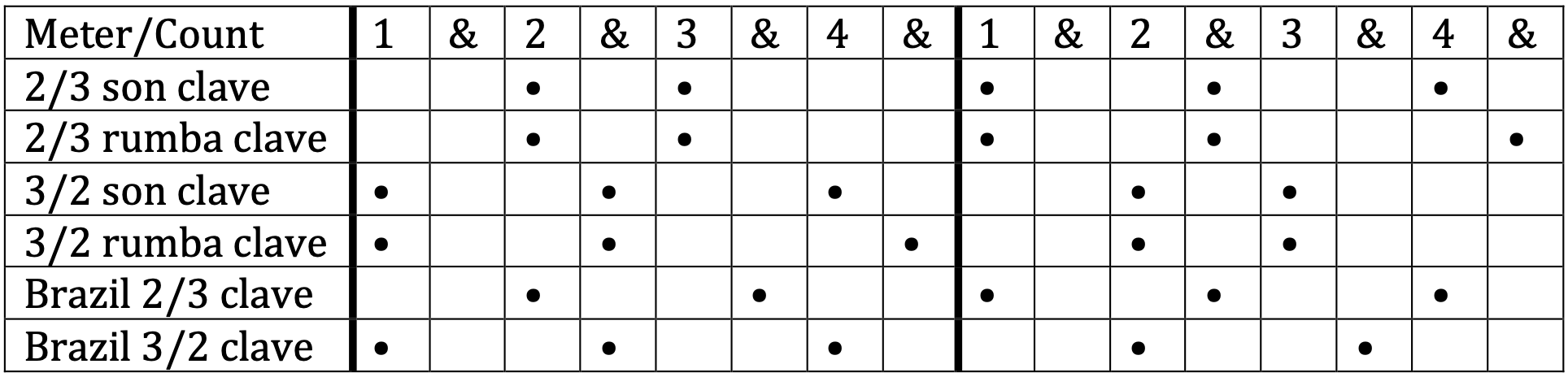

Latin (American) Clave

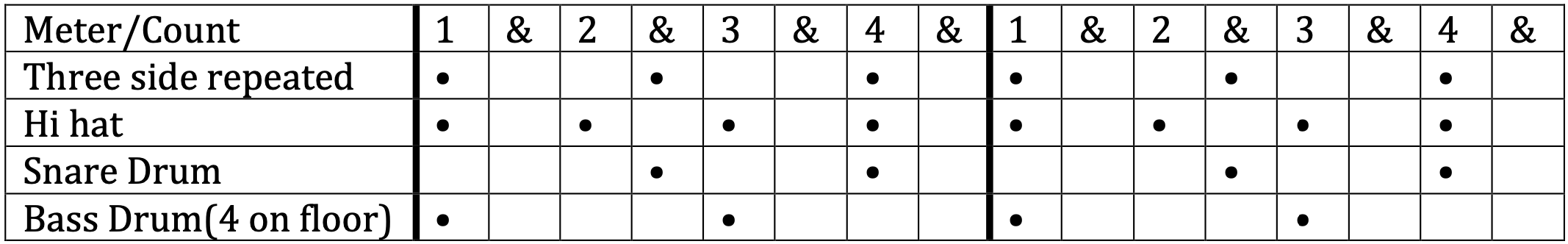

African polyrhythmic drumming made its way to the diaspora in the Caribbean, South, and North America. To the untrained ear the differences in Afro- Caribbean drumming and African drumming are sometimes hard to perceive. The most helpful signifier of Latin American drumming is its reliance on clave. Clave is the timeline pattern that works within a meter to hold Afro-Caribbean music together. Clave has a direct link to West-African (Yoruba of modern Nigeria) timeline patterns. Clave can be heard in much Latino music as a foundational pattern. The influence of Afro-Cuban styles of the mid 20th century has much to do with the appearance of Clave in styles of music like rumba, conga, cha-cha, son, mambo, samba, salsa, songo, timba, bossa-nova, bolero, bachata, candombe, bomba, plena, and reggaeton. While not always present in sound the feeling of clave is a necessary aspect of most Latin music. Clave patterns have a three side and a two side. This means that in every two measure pattern one measure contains three notes of the clave and one measure contains two (See Figure 10).

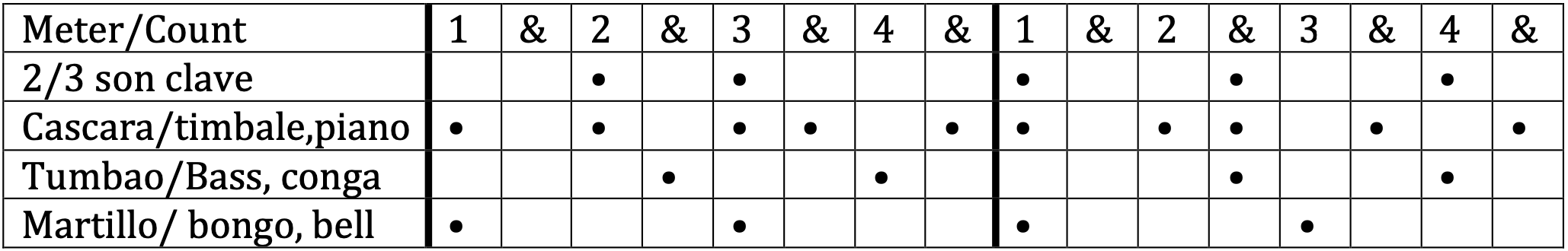

Salsa is an Afro-Cuban genre that originated in the 20th century in New York combining Cuban, Puerto Rican, Domenican, and American sensibilities and styles. The polyrhythms in salsa are heard in the rhythms of all of the instruments, not just the drums (See Figure 11).

Modern music in genres such as plena, soca, bomba, merengue, cumbia, timba, tango, and reggaeton often have a heavy emphasis on repeated three side of the clave or the tumbao pattern. Sometimes the two side is not heard (but it is often felt by players and dancers). This is often heard in styles that use bass drum emphasis on beats one and three of a quadruple measure (“four on the floor” across two bars)(See Figure 12).