6.4: Music of the Mendelssohns

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

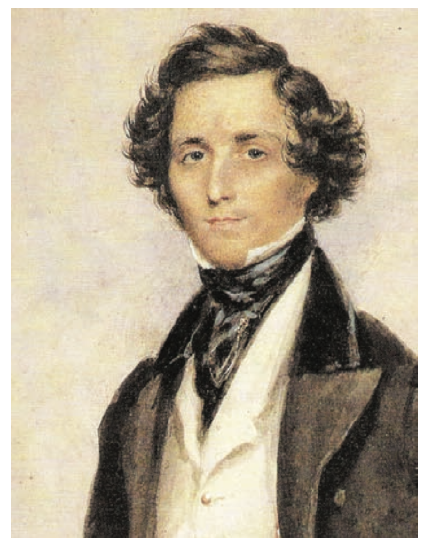

In terms of musical craft, few nineteenth-century composers were more accomplished than Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1809-1847). Growing up in an artistically-rich, upper-middle class household in Berlin, Germany, Felix Mendelssohn received a fine private education in the arts and sciences and proved himself to be precociously talent- ed from a very young age. He would go on to write chamber music for piano and strings, art songs, church music, four symphonies, and oratorios as well as conduct many of Beethoven’s works as principal director of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra. All of his music emulates the motivic and organic styles of Beethoven’s compositions, from his chamber music to his more monumental compositions. Felix was also well-versed in the musical styles of Mozart, Handel, and Bach.

Felix descended from a family of prominent Jewish intellectuals; his grandfather Moses Mendelssohn was one of the leaders of the eighteenth-century German Enlightenment. His parents, however, seeking to break from this religious tradition, had their children baptized as Reformed Christians in 1816. Anti-Semitism was a fact of life in nineteenth-century Germany, and such a baptism opened some, if not all, doors for the family. Most agree that in 1832, the failure of Felix’s application for the position as head of the Berlin Singakadmie was partly due to his Jewish ethnicity. This failure was a blow to the young musician, who had performed frequently with this civic choral society, most importantly in 1829, when he had led a revival of the St. Matthew Passion by Johann Sebastian Bach. Although today we think of Bach as a pivotal figure of the Baroque period, his music went through a period of neglect until this revival.

Initially, Felix’s father was reluctant to see his son become a professional musician; like many upper-middle class businessmen, he would have preferred his son enjoy music as an amateur. Felix, however, was both determined and talented, and eventually secured employment as a choral and orchestral conductor, first in Düsseldorf, and then in Leipzig, Germany, where he lived from 1835 until his death. In Leipzig, Felix conducted the orchestra and founded the town’s first music conservatory.

Felix’s music was steeped in the styles of his predecessors. Although he remained on good terms with more experimental composers of his day, including Hector Berlioz and Franz Liszt, he was not fond of their music. It is not surprising, then, that he composed in genres passed down to him, including the symphony, string quartet, and oratorio.

One of his last works, his oratorio Elijah, was commissioned by the Birmingham Festival in Birmingham, England. The Birmingham Festival was one of many nineteenth-century choral festivals that provided opportunities for amateur and professional musicians to gather once a year to make music together. Mendelssohn’s music was very popular in England, and the Birmingham Festival had already performed another Mendelssohn oratorio in the 1830s, giving the premier of Elijah in English in 1846.

Elijah is interesting because it is an example of music composed for middle-class music-making. The chorus of singers was expected to be largely made up of musical amateurs, with professional singers brought in to sing the solos. The topic of the oratorio, the Hebrew prophet Elijah, is interesting as a figure significant to both the Jewish and Christian traditions, both of which Felix embraced to a certain extent. (In general, Felix was private about his religious convictions, and interpretations of Elijah as representing the composer’s beliefs will always remain somewhat speculative.) This composition shows Felix’s indebtedness to both Baroque composers Bach and Handel, while at the same time it uses more nineteenth-century harmonies and textures.

The following excerpt is from the first part of the oratorio and sets the dramatic story of Elijah’s calling the followers of the pagan god Baal to light a sacrifice on fire. Baal fails his devotees; Elijah then summons the God of Abraham to a display of power with great success. The excerpt here involves a baritone soloist who sings the role of Elijah and the chorus that provides commentary. Elijah first sings a short accompanied recitative, not unlike what we heard in the music of Han- del’s Messiah. The first chorus is highly polyphonic in announcing the flames from heaven before shifting to a more homophonic and deliberate style that uses longer note values to proclaim the central tenet of Western religion: “The Lord is God, the Lord is God! O Israel hear! Our God is one Lord, and we will have no other gods before the Lord.” After another recitative and another chorus, Elijah sings a very melismatic and virtuoso aria.

Elijah was very popular in its day, in both its English and German versions, both for music makers and musical audiences, and continues to be performed by choral societies today.

Elijah - "O Thou, who makest," "The Fire Descends," "Is not His word like a fire!. Performed by the Texas A&M Century Singers with orchestra and baritone soloist Weston Hurt." https://youtu.be/pUOxpjiltGU?list=PL2DA5013E20B3E14A

- Composer: Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy

- Composition: Excerpts from Elijah

- Date: 1846

- Genre: Recitative, choruses, and aria from an oratorio

- Form: Through-composed

- Nature of Text:

Elijah (recitative): O Thou, who makest Thine angels spirits; Thou, whose ministers are flaming fires: let them now descend!

The People (chorus): The fire descends from heaven! The flames consume his offering! Before Him upon your faces fall! The Lord is God, the Lord is God! O Israel hear! Our God is one Lord, and we will have no other gods before the Lord.

Elijah (recitative): Take all the prophets of Baal, and let not one of them escape you. Bring them down to Kishon’s brook, and there let them be slain.

The People (chorus): Take all the prophets of Baal and let not one of them escape us: bring all and slay them!

Elijah (aria): Is not His word like a fire, and like a hammer that breaketh the rock into pieces! For God is angry with the wicked every day. And if the wicked turn not, the Lord will whet His sword; and He hath bent His bow, and made it ready.

- Performing Forces: Baritone soloist (Elijah), four-part chorus, orchestra

- What we want you to remember about this composition:

- It’s an oratorio composed for amateurs and professionals to perform at a choral festival

- It uses traditional forms of accompanied recitative, chorus, and aria to tell a dramatic story

- Other things to listen for:

- A much larger orchestra than heard in the oratorios of Handel

- A very melismatic and virtuoso aria in the style of Handel’s arias

- More flexible use of recitatives, arias, and choruses than in earlier oratorios

- More dissonance and chromaticism than in earlier oratorios

|

Timing |

Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture |

Text and Form |

|---|---|---|

|

0:00 |

Solo Baritone (Elijah); Orchestra. Minor key, orchestra punctuates the ends of each of singer’s phrases. |

Accompanied recitative: |

|

0:32 |

Chorus and Orchestra. |

Chorus: |

|

1:29 |

Chorus and Orchestra. |

Chorus: |

|

2:25 |

Soloist and Orchestra. Melody and texture as before. |

Accompanied recitative: |

|

2:40 |

Chorus and Orchestra. Homophonic, minor key. |

Chorus: |

|

2:51 |

Soloist and Orchestra. |

Aria: |

Felix was not the only musically precocious Mendelssohn in his household. In fact, the talent of his older sister Fanny (1805-1847) initially exceeded that of her younger brother. Born into a household of intelligent, educated, and socially-so- phisticated women, Fanny was given the same education as her younger brother (see figure of Fanny Mendelssohn, sketched by her future husband: https:// en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Fanny_Mendelssohn#/media/File:Fannymendels- sohn-improved.jpg). But for her, as for most nineteenth-century married women from middle-class families, a career as a professional musician was frowned upon. Her husband, Wilhelm Hensel supported her composing and presenting her music at private house concerts held at the Mendelssohn’s family residence. Felix also supported Fanny’s private activities, although he discouraged her from publishing her works under her own name. In 1846, Fanny went ahead and published six songs without seeking her husband’s or brother’s permission.

Musicians today perform many of the more than 450 compositions that Fanny wrote for piano, voice, and chamber ensemble. Among some of her best works are the four-movement Piano Trio in D minor, Op. 11, and several volumes of songs and piano compositions. This piano trio holds its own with the piano trios, piano quartets, piano quintets, and string quartets composed by other nineteenth-century composers, from Beethoven and Schubert to the Schumanns, Johannes Brahms, and Antonin Dvorak.