13.9: Yo-Yo Ma

- Page ID

- 92204

Perhaps the most visible and influential individual to make a career as a classical crossover artist has been cellist Yo-Yo Ma. His work has embraced a range of folk and non-Western musical styles, with the result that he has successful bestowed his own cultural prestige on a large number of performers and traditions that might otherwise not have come into contact with the classical establishment. His projects have resulted in the creation of a lot of excellent music and the introduction of new sounds to classical audiences.

Classical Mastery

Yo-Yo Ma was born in Paris to Chinese parents, but his family immigrated to the United States when he was seven. He first gained prominence as a child prodigy. Almost immediately after his arrival in the States, Ma played for Presidents John F. Kennedy and Dwight D. Eisenhower at a Kennedy Center benefit concert that was broadcast on national television.12 This was the first in a series of prominent performances and television appearances that introduced Ma to the American public.

12. A young Yo-Yo Ma played cello on live television in 1962.

After earning his bachelor’s degree at Harvard University in 1976, Ma embarked on what could have been a typical concert career. He appeared as a soloist with orchestras around the world, collaborated with chamber musicians, and released recordings, eleven on which won Grammys between 1985 and 1998. The first of these award-winning recordings offered Ma’s interpretation of the complete Bach cello suites (see Chapter 12)—a rite of passage for any cellist who wants to be counted among the greats.

13. Yo-Yo Ma has proven his mastery of the classical cello literature. Here he plays the Prelude to Bach’s Suite No. 1.

Ma still performs these pieces regularly. He has presented the complete suites to crowds numbering in the tens of thousands at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles and the Jay Pritzker Pavilion in Chicago, but he also played movements from the suites at the one-year national September 11 memorial service, the funeral for Senator Edward M. Kennedy, and the service held to honor victims of the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing. In 2019, he featured the Prelude to Suite No. 1 in G major13—certainly the best-known movement from the suites—in a video meant to express the many ways in which the arts bring communities together. He issued an invitation for people around the world to submit videos on the theme of self- expression and community building. Many of these were then integrated in the final video.

Despite his success on the concert stage, however, Ma soon embarked on a series of collaborations that brought him into contact with non-classical performers and genres. By doing so, he clearly indicated his belief that examples of “good music” can be found in all traditions, and that quality is determined by the level of execution and creativity that characterize a performance. Early in his journey, Ma collaborated with a team of world-class tango musicians to record The Soul of the Tango (1997). This Grammy-winning album contributed to the elevation of tango from its undeniably humble roots.

Tango

Tango originated in the slums of Buenos Aires, Argentina, in the late 19th century. A popular dance style, the tango was inherently international: It was driven by an instrument brought to South America by German immigrants, the bandoneon (a type of push-button accordion) and capitalized on the syncopated rhythms of rural gauchos (cowboys) and African slaves. The lyrics to early tango songs described the hardships of life in the slums, while the accompanying dance reflected the violence of knife duels, the characteristic posture of the good-for- nothing young man, and the ritualistic domination of the female dancer by her male partner. The tango rhythm is built on a quadruple-meter framework with an emphasis on the second half of the second beat.

The tango was at first treated with contempt in its native Argentina. The dance and its accompanying music, after all, were associated with poverty, seedy establishments, and questionable morals. In 1907, however, the tango made a hit in Paris, where it acquired cultural cachet. By the 1920s, it had been embraced around the world, but in the 1930s its popularity began to fade (in part because the Great Depression excited an appetite for more cheerful music). Later in the century, however, Astor Piazzolla (1921-1992) would reinvent the tango for the concert hall, composing nuanced and dramatic pieces that were intended for listening, not dancing.

We will consider Yo-Yo Ma’s recording of Piazzolla’s famous “Libertango,” which he recorded with Leonardo Marconi on piano, Antonio Agri on violin, Hector Console on bass, Horacio Malvicino on guitar, and Néstor Marconi on bandoneon. The title incorporates the Spanish word for “liberty”—a reference to Piazolla’s new style, which he launched with the 1974 publication and recording of this composition. Any performance of “Libertango” is immediately recognizable, due to the catchy ostinato played by the bandoneon. The compositions itself is fairly simple: After an introduction, which establishes the ostinato and harmonic progression, we hear the A section twice. This is followed by the B section, which begins with contrasting material but concludes with a variation on the first half of the A melody. Then the ostinato returns, serving as a basis for improvisation.

|

Time |

Form |

What to listen for |

|---|---|---|

|

0’00 |

Ostinato |

The bandoneon establishes the ostinato whilethe piano plays a syncopated rhythm known as the tresillo |

|

0’26” |

A |

The A melody is played in the cello |

|

0’54” |

A |

The A melody is played by the cello and violin in octaves |

|

1’22” |

B |

The B melody is played by the bandoneon |

| 1’37” | A’ | The bandoneon plays a variation on the first half of the A melody, which is now combined with the ostinato; the cello and violin play a countermelody |

| 1’50” | Ostinato | This time, the cello and violin double the bandoneon on the ostinato |

| 2’18” | Ostinato | Ostinato with The guitar player improvises a solo over the improvisation ostinato |

Throughout the recording, we can clearly hear the tresillo rhythm that is characteristic of much Latin American music. This rhythm has its roots in West African music, and it entered the Latin American mainstream when the traditions of enslaved Africans combined with the folk and popular practices of both indegenous peoples and colonial powers. The same rhythm can also be heard in African-derived musics of the United States, such as ragtime. The tresillo rhythm can be counted as 3+3+2. Each count is a half-beat, such that one measure in quadruple meter contains eight counts. In our recording of “Libertango,” the tresillo rhythm is heard primarily in the piano.

Appalachian Music

At about the same time, Ma also turned his attention to the folk music of the United States. He teamed up with celebrity fiddler Mark O’Connor and renowned bass player Edgar Meyer to record two albums, Appalachia Waltz (1996) and Appalachian Journey (2000), each of which contains fiddle tunes, songs, and new compositions inspired by the American folk sound. The trio did not attempt to reproduce authentic performing styles. Instead, they brought their own skills and backgrounds to the creation of unusual arrangements that balanced traditional material with novel interpretation.

We will consider their rendition of “Fisher’s Hornpipe” from Appalachian Journey. This tune has been convincingly attributed to James A. Fishar, who served as music director at Covent Garden opera house in London in the 1770s. It appeared as “Hornpipe #1” in his 1778 collection of dance tunes. Whether or not Fishar composed the tune, it quickly gained popularity. Today it can be heard all over the British isles, in Canada, and in the United States, where it first appeared in print in 1796. There are countless versions—a symptom of the oral tradition, in which tunes are learned not from notation but by ear. Appalachian fiddlers would most likely have learned “Fisher’s Hornpipe” from travelling dance musicians and adapted it to their own tastes.

For comparison, we might consider Tommy Jarrell’s version of “Fisher’s Hornpipe,”14 which he learned from his father. This is an example of the traditional fiddling style known today as Round Peak, named after a prominent geological feature near Mt. Airy, NC. Jarrell provides harmony by playing multiple strings at the same time and rhythm by employing syncopated bowing patterns. As such, he doesn’t particularly require accompaniment.

14. This recording of “Fisher’s Hornpipe” by Tommy Jarrell provides a good example of a traditional Appalachian rendition.

Ma and company’s rendition is quite different. O’Connor is joined on the fiddle by bluegrass legend Allison Kraus. Although they play the same instrument as Jarrell, their technique could not contrast with his more greatly than it does. Each plays only a single melodic line, and does so with great precision and clarity. The slower tempo allows each note to sparkle. Occasionally we can hear vibrato—a technique that Jarrell would never employ. When accompanying other instruments, O’Connor and Kraus evoke some of the same rhythms as Jarrell, but their rendition of the melody is less syncopated.

Perhaps most importantly, the version of “Fisher’s Hornpipe” on Appalachian Journey takes the original tune far outside of its folk framework. When Jarrell plays “Fisher’s Hornpipe,” he simply repeats the A and B strains until he decides that it is time to stop. His version is in the key of D, and it most certainly stays there. O’Connor and Kraus (soon joined by Meyer and Ma) begin with a fairly straightforward rendition of the tune, but after a few times through they switch to a groovy rhythmic pattern. Then, as Ma takes the melody, they modulate (change keys)—twice. Next, each player takes a turn with the A or B section, adding ornaments as if trying to outdo the person who played before. After this, they break into a polyphonic, four-part version of the tune that includes several countermelodies. The recording ends with even more key changes and virtuosic, high-range playing from Ma.

|

Time |

Form |

What to listen for |

|---|---|---|

|

0’00” |

A |

The two violins play the A strain in harmony (note: Jarrell begins with the other strain, making this his B strain) |

|

0’10” |

A |

Addition of bass pizzicato |

| 0’21” | B B | Addition of cello harmony |

| 0’42” | B’ | The two violinists play a variation on the B strain 1’04” A’ A’ The two violinists play a variation on the A strain |

| B’ |

The key modulates up one step and the cello plays 1’25” A the A strain, which is extended by a brief concluding passage |

|

| 1’39” |

A |

The key changes again as a solo violin plays the A strain |

| 1’49” | A | The other violin plays the A strain with additional ornamentation |

| 1’59” | B | The cello plays the B strain 2’09” B The bass plays the B strain |

| 2’21” | B B | One violin plays the B strain while the other instruments provide new countermelodies in a polyphonic texture; the key changes for the second statement of the B strain, the last phrase of which is repeated |

| 2’46” | A’ A | The A’ variation returns for one statement before the cello plays the A strain. The key modulates up by one step for another A’ |

| 3’08” | A’ | A statement; it modulates up by yet another step for a cello statement of the A strain |

| 3’30” | Coda | A concluding passage echoes the opening motif of the A strain |

Silk Road Project

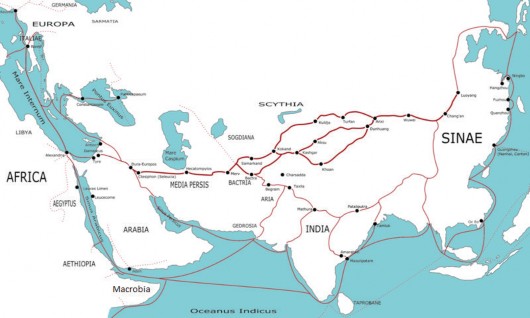

Ma’s most significant and lasting foray outside of the European concert tradition, however, began in 1998 and has carried into the present day. He founded the Silk Road Project with the aim of bringing together musicians and cultures from across the regions formerly traversed by the Silk Road—the trade route, spanning from Italy to Japan, that shaped Europe, the Middle East, North Africa, and Asia beginning in the second century BCE. For Ma, the Silk Road was a symbol of intercultural exchange. For two millennia, the Silk Road moved clothing, artifacts, musical instruments, songs, stories, and religious beliefs from one end of the known world to the other. Ma has described the historical Silk Road as “a model for productive cultural collaboration, for the exchange of ideas and traditions alongside commerce and innovation”—values that he wants to promote in the modern world.

Although the Silk Road Project has grown into a multifaceted arts organization— Silkroad—that pursues a variety of initiatives, we will consider only the activities of the Silkroad Ensemble, a collective of international virtuosi who blend the instruments, styles, and techniques of various musical traditions. The ensemble contains nearly sixty members (although only a dozen or so perform together on any given occasion) and has been active across the globe. Its members record albums (seven in the first two decades), give concerts, host festivals, and conduct clinics for students of all ages.

The music played by the Silkroad Ensemble comes from a variety of sources. Sometimes, individual members share traditional pieces from their own cultural backgrounds. The various performers then find a way to interpret that music in a way that makes sense to each of them, and the ensemble works together to develop creative arrangements. Sometimes, the Silkroad Ensemble—like Roomful of Teeth, discussed above—commissions composers to write works for their unique performing forces and abilities. And sometimes, the ensemble adapts pieces of music that have been written for other performers. In all cases, their repertoire blends cultural influences. However, it is very important to Yo-Yo Ma that the Silkroad Ensemble treat its sources with respect and avoid exoticizing non-Western musical traditions—like we saw happen in Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker (Chapter 4).

We will consider one of the Silk Road Ensemble’s most popular numbers, “Arabian Waltz.” This piece was written and recorded by the Lebanese composer and oud player Rabih Abou-Khalil in 1996. Although well- versed in traditional Arab music, Abou- Khalil is equally knowledgeable of Western traditions, having studied flute at the Academy of Music in Munich, Germany. His compositions blend Arab scales, textures, and rhythms with influences from jazz, rock, and European concert music. “Arabian Waltz” was written for oud, string quartet (a European ensemble), and traditional Arab frame drums.

The original recording featured Abou-Khalil in collaboration with the Balanescu Quartet—an ensemble led by Romanian violinist Alexander Bălănescu that specializes in experimental music.

|

“Arabian Waltz” Composer: Rabih Abou-Khalil. Performance: Rabih Abou-Khalil, The Balanescu Quartet (1996) |

Clearly, “Arabian Waltz” was a cross- cultural work from its inception. In the hands of the Silkroad Ensemble, however, it has absorbed an even greater depth of international influence. We will consider a live performance that the ensemble gave in 2009 at the Park Avenue Armory in New York City. The ensemble, on this occasion, consisted of two violins, viola, cello, string bass, pipa (a Chinese lute—see Chapter 6), sheng (the Chinese mouth organ—see Chapter 4), shakuhachi (a Japanese flute), tabla (North Indian drums—see Chapter 6), various Middle Eastern frame drums (see Chapter 8), and janggu (a Korean drum). This is unquestionably an extraordinary assortment of instruments, each played by a master of the respective tradition.

The Silkroad Ensemble’s performance of “Arabian Waltz” begins just as Abou-Khalil’s had, with the sound of Arab frame drums. From the start, however, the ensemble members leave their unique stylistic fingerprints on this rendition. The principal melody is first heard in the shakuhachi, played by Kojiro Umezaki. Umezaki plays the melody—itself unmistakably Middle Eastern—in a Japanese style, introducing the typical embellishments that are idiomatic to the shakuhachi. Another remarkable contribution comes from the tabla player, Sandeep Das, who likewise plays his instrument just as he would in a North Indian context. In the second half of the performance, Das is featured in a solo that combines the sound of the tabla with the other drums, producing an unprecedented aggregation of percussive timbres.

|

“Arabian Waltz”.16. Composer: Rabih Abou-Khalil. Performance: Yo-Yo Ma, The Silkroad Ensemble (2009) |