13.3: 1965 - Aaron Copland, Appalachian Spring

- Page ID

- 92084

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Of all the compositions ever to win the Pulitzer Prize, none may have been so warmly embraced by the listening public as Aaron Copland’s Appalachian Spring. This orchestral work—first conceived of as a ballet, but more frequently performed on the concert stage—has never left the repertoire, and it is regularly performed in versions for both chamber orchestra and full orchestra. Appalachian Spring also helped to solidify Copland’s reputation as a composer of explicitly “American” music.

Indeed, Copland-esque soundtracks have been used to accompany on-screen cowboys and ranchers ever since the 1940s, and we have long accepted that the sound of Copland is the sound of rural America.

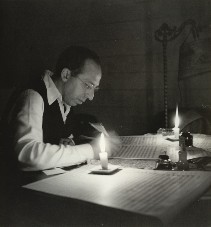

Copland’s Career

Aaron Copland (1900-1990) did not start off his career writing folksy-sounding concert pieces. His earliest interest lay in synthesizing jazz and classical idioms, as we saw George Gershwin do with his 1924 Rhapsody in Blue. Copland, however, did not meet with Gershwin’s success. Gershwin was an uneducated popular song composer who rose to the challenge of writing a sophisticated concert work and was therefore lauded for his accomplishments. Copland, on the other hand, had the benefit of a rigorous education, and in 1924 was concluding three years of study in Paris with the most renowned composition teacher of the 20th century, Nadia Boulanger. When he incorporated jazz into his early works, therefore, he was scorned by highbrow critics who thought that by doing so Copland was degrading his art. Copland gave up the project and instead wrote sophisticated concert music in a modern style for the rest of the 1920s.

The Great Depression convinced many composers of art music to adopt a more commercial style. They did so both out of necessity and for ideological reasons. It was not practical to write elite music for small audiences during a period of such hardship, but it also seemed unethical. What was the purpose of art if not to comfort people in their time of suffering? Copland was also interested in using music to further left-wing political causes in which he had taken an interest. He was particularly influenced by the rising interest among young progressives in American folk music, which was understood to represent the common people and their struggles.

Folk tunes had a major impact on Copland as he began to develop his unique musical language. All three of the ballets that cemented his reputation as a composer used folk melodies to portray rural America. Billy the Kid (1938) combines a variety of cowboy songs with Mexican folk music to tell the story of the famous outlaw. Rodeo (1942), also set on the Western frontier, features an Appalachian fiddle tune called “Bonaparte’s Retreat” in its final scene. And Appalachian Spring (1944) contains a set of variations on the Shaker hymn tune “Simple Gifts.”

Appalachian Spring

Before looking inside Appalachian Spring, however, we need to know a little more about how this ballet came to be. In 1942, Copland was commissioned to write a ballet “on an American theme” by dancer Martha Graham and music patron Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge. Copland completed the 25-minute score without a narrative in mind—his aim was simply to write music that sounded “American” and contained dramatic contrasts. In fact, he had no idea what the ballet was to be about until he saw it just a few days before the October 1944 premiere at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. He later loved to talk about the compliments he received from listeners who felt that he had perfectly captured the Appalachian mountains in music, when in fact no such idea had been in his mind while composing.

The dramatic narrative, which was developed by Graham after she heard the music, concerns the marriage of a young farming couple. The eight brief scenes portray the community coming together to celebrate the wedding, the various emotions felt by the bride and groom, and the adventure of embarking upon married life. The title, which replaced Copland’s working title, Ballet for Martha, was drawn from a line of Hart Crane’s 1930 poem “The Dance.”

Scene One

We will take a look at the first, second, and seventh scenes to get an idea about how Copland created “American”-sounding music. After seeing the ballet performed, he wrote his own summaries of the music and action incorporated into each scene. To describe scene one, he wrote “Very slowly. Introduction of the characters, one by one, in a suffused light.”1 In this excerpt, we can hear several of the techniques that characterize Copland’s music. He creates the impression of a wide open space by juxtaposing high and low sounds. He captures a sense of stillness by writing music that moves slowly and seldom changes harmony. Finally, his melodies outline triads in different key areas. This means that scene one is not in any particular key, and is therefore polytonal. But the music is not jarring or uncomfortable, like that which we heard in The Rite of Spring. Instead, Copland creates a floating effect: we often don’t know where we are or where we are going, but the experience is pleasant.

|

Scene One from Appalachian Spring. 1. Composer: Aaron Copland. Performance: Harmonie Ensemble/New York, conducted by Steven Richman (2004) |

Scene Two

The mood suddenly changes with scene two, which Copland described as follows: “Fast/Allegro. Sudden burst of unison strings in A major arpeggios starts the action. A sentiment both elated and religious gives the keynote to this scene.”2 Copland continues to employ polytonality, but we are now dancing instead of floating. He introduces a variety of exciting rhythmic elements, including mixed meter, that make it difficult (or even impossible) to tap your foot along to the music. The elated sentiment that Copland describes is communicated by means of fast tempos and disjunct melodies that include large leaps. The religious sentiment is communicated through a sequence of powerful, emotive harmonies.

|

Scene Two from Appalachian Spring. 2. Composer: Aaron Copland. Performance: Harmonie Ensemble/New York, conducted by Steven Richman (2004) |

Scene Seven

Copland’s use of a traditional tune comes in scene seven:3

Calm and flowing/Doppio Movimento. Scenes of daily activity for the Bride and her Farmer husband. There are five variations on a Shaker theme. The theme, sung by a solo clarinet, was taken from a collection of Shaker melodies compiled by Edward D. Andrews, and published under the title “The Gift to Be Simple.” The melody borrowed and used almost literally is called “Simple Gifts.”

|

Scene Seven from Appalachian Spring 3. Composer: Aaron Copland Performance: Harmonie Ensemble/New York, conducted by Steven Richman (2004) |

Copland regularly relied on the work of scholars and song collectors. In this case, he turned to Dr. Andrews’s 1940 volume The Gift to Be Simple: Songs, Dances and Rituals of the American Shakers for source material. Copland first presents the hymn tune in the solo clarinet. Like Bartók (see Chapter 9), he does not alter the melody at all, but he does provide an original and very modern harmonization. Copland then leads the listener through a series of variations, each of which is more rhythmically exciting and virtuosic than the last.

It is interesting to note that Copland was in fact one of the early champions of music appreciation as a subject of study. He sought to reveal the secrets of the concert hall to as many new listeners as possible, and he dedicated much of his time to talking and writing about music for the public. His 1937 volume What To Listen For In Music is an early classic of the music appreciation literature and is still in print.