12.7: Dance Music in Concert Settings

- Page ID

- 92194

In the last section, we considered four musical examples that were all created expressly to facilitate dancing. That doesn’t mean that this music can’t be enjoyed by a listener—indeed, it often is. However, these have been examples of practical dance music.

In the next section, we will consider dance rhythms and forms adapted to purely musical ends. This essentially takes us back to where the chapter started, with John Philip Sousa’s concert marches. Here, however, we take a look at two dramatically different composers who each used the popular dance styles of their time and place to inform music that was meant primarily for listening.

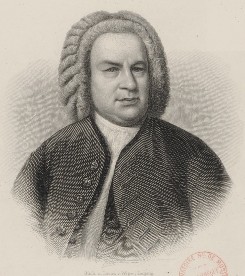

Johann Sebastian Bach, Cello Suites

We have already considered the career of J.S. Bach, one of the most respected and influential composers in the European tradition. In Chapter 11, we examined two pieces of music that he created for use in the Lutheran church. Bach held a series of positions as organist or music director with various courts and municipalities, and in each of these positions he was required to compose music of various types in order to satisfy the needs of his employer.

Bach and the Baroque Dance Suite

Although most of his jobs required the production of church music, one did not: his position as music director at the court of Leopold, Prince of Anhalt-Köthen, which he held from 1717 to 1723. Because the Prince was a Calvinist, he had little need for church music; Calvanist churches of the time rejected musical instruments and restricted singing to the modest chanting of Psalms. A piece of music like “Sleepers, Wake” (Chapter 11), therefore, would not have been welcome. The Prince, however, maintained a lavish court, and he was particularly fond of music. He sang and played the violin, viola da gamba, and harpsichord. Although his parents had declined to spend money on music, Prince Leopold assembled a large court orchestra of eighteen musicians and recruited the finest composer in the region: Bach. During Bach’s employment, Prince Leopold called upon him to produce instrumental music and cantatas for the purpose of entertaining guests, celebrating anniversaries, and generally ornamenting life in the palace.

While at the Prince’s court, Bach adopted the practice of composing dance suites. The popularity of dance suites stemmed from the desire of minor German monarchs to emulate the court of the French king, which was renowned for its sophistication and luxury. The dance suite was pioneered by the German composer Johann Jacob Froberger (1616-1667), who traveled throughout Europe absorbing and adapting the musical styles that he heard at courts in France, Italy, England, and Belgium. Froberger was able to bring this music to German courts in the form of dance suites, which were associated with cosmopolitan sophistication. Unlike Froberger, Bach never left left Germany. All the same, he became a master of musical forms and styles from throughout the continent.

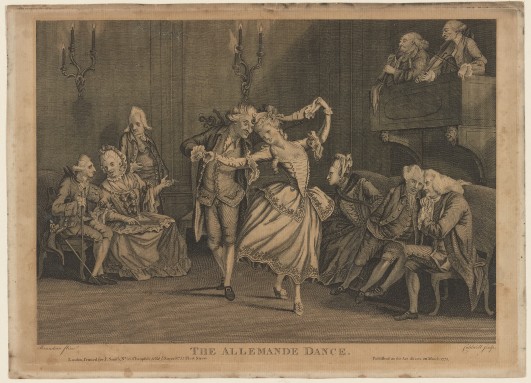

The dance suite consists of movements inspired by court dances from various European countries. At the core of the dance suite are the Allemande, Courante, Sarabande, and Gigue. To these may be added any number of other dances, including the Menuet, Bourée, Gavotte, and Loure. In addition, some dance suites begin with a Prelude, which establishes the key area for the suite and sets the mood.

The sources of the four required movements reveal the international character of the dance suite. The Allemande traces its origins to Germany, although by the time it was integrated into the dance suite it had been adopted and transformed by French courts (the French name for Germany is Allemagne). Although the Allemande was initially a fast-paced dance in quadruple meter, the French slowed it to a stately tempo. The Courante can be of two types, French or Italian. While both are in triple meter, the French is slow and dignified, while the Italian is

quick and lively. The Sarabande originated in Mexico, where it was a quick and salacious dance accompanied by castanets. After being banned from the Spanish courts for alleged obscenity, however, it was reinvented as a slow and dignified triple-meter dance with rhythmic emphasis placed on the second beat. And finally, the Gigue traces its roots to the English and Irish jig, a fast dance in compound duple meter (meaning that each pulse is divided into three sub-pulses).

In the context of a dance suite, all four of these movements are always cast in binary form. Each part is repeated, with the resulting form of A A B B. This should strike the reader as familiar, for it is also the form of the Appalachian dance tune “Arkansas Traveler.” Likewise, it can be found in the folk dances of the British Isles and Europe. Bach refined the form in his own dance suites, starting both the A and B sections with similar melodic material in different keys. Bach’s B sections usually start in the dominant key, which is based on the fifth scale degree of the original key. For example, if the suite is in the key of C major, each A section will start in the key of C, while each B section will start in the key of G.

Bach wrote a large number of dance suites for many different configurations of instruments. These include four suites for orchestra, twenty-eight for keyboard, three for lute, six for violin, six for cello, and one for flute. A word of caution, however, for it is in fact very difficult to count Bach’s suites. He gave such works a variety of titles, including Suite, Partita, and Overture, and only a handful—six keyboard partitas—were published in his lifetime. The others have survived only in manuscript form, since they were intended for private court performance, not widespread distribution.

In the court of Prince Leopold, dance suites were performed solely as musical entertainment. The dances themselves had largely fallen out of fashion, but their rhythms and gestures lived on in the suites. We will consider two movements from two of Bach’s suites for solo cello: the Courante from Suite No. 2 in D minor and the Sarabande from Suite No. 4 in E-flat major.

Bach’s Cello Suites

The six suites for solo cello are among Bach’s most influential compositions. All cellists play at least some of the suites, although the last two present major challenges: Suite No. 5 in C minor requires that the cellist change the pitch of their highest string, while Suite No. 6 in D major seems to have been written for a related but higher-pitched string instrument, with the result that it is exceedingly difficult to perform on a modern cello. Today, it is common to hear these pieces in performance, and they have been recorded countless times.

Despite their ubiquity, however, a great deal of mystery surrounds the origin of the cello suites. To begin with, in the time of Bach it was very uncommon to write music featuring the cello, and essentially unheard of to write for solo cello. The cello was part of the basso continuo section, and was therefore relegated to strictly accompanimental roles. Bach would have written these suites for a specific performer (or performers) at the court of Prince Leopold, so we can assume that he had a close relationship with one or more accomplished players who would have been able to bring the music to life. The legacy of these suites is further complicated by the fact that the original manuscripts have not survived. Instead, we have been left with copies made by Bach’s second wife, Anna Magdalena. It is worth considering her role in his life with some care. When Bach joined Prince Leopold’s court, he brought with him his first wife, Barbara. In 1720, however, Barbara died while Bach was traveling with the Prince. Anna Magdalena was the daughter of a court trumpeter and a court singer herself. She married Bach in 1721, at the age of 20. In addition to raising their many children, Anna Magdalena provided Bach with invaluable services as a copyist and perhaps even collaborator. She would copy out individual parts from his orchestral scores and also make clean copies of his roughly worked-out draft manuscripts. Because the only surviving manuscripts for the six cello suites are in her hand, there has been some controversy concerning the accuracy of the bowings and articulations, which have a significant effect on the performance of the music. Anna Magdalena’s copy is also free of dynamic markings and other phrasing instructions, with the result that modern performers have to make many important decisions about how to interpret these pieces.

It is hard to determine exactly how the Courante was danced. On the one hand, dance notation is notoriously vague. On the other, there were many variations of the Courante, and it is known to have transformed over time. However, we can make generalizations. The word courante (or the Italian corrente) means “running,” and the dance has been described as containing quick back-and-forth steps, little leaps, and stately glides. It was performed by couples. Bach’s Courante from Suite No. 2 certainly reflects the activity of such a dance: The melody moves at a quick but regular pace, offering few chances for repose.

|

Time |

Form |

What to listen for |

|---|---|---|

|

0’00” |

A |

The tempo is steady throughout, and there is not much rhythmic variety |

|

0’31” |

A |

The A section is repeated |

|

0’59” |

B |

The B section starts with the same melodic motif as the A section, but it is in a higher range |

|

1’28” |

B |

The B section is repeated |

Although the Sarabande was initially, in the words of one priest, “a dance and song so loose in its words and so ugly in its motions that it is enough to excite bad emotions in even very decent people,” by Bach’s time it had been thoroughly reformed. The Sarabande from Suite No. 4 reflects the slow, stately dance that had been popular in French courts of the previous century. It contains uneven dotted rhythms throughout—rhythms that were intimately associated with French royalty and pomp. This contributes to the movement’s serious and dignified tone.

|

Sarabande from Cello Suite No. 4 in E-flat major 12. Composer: Johann Sebastian Bach Performance: Phil Snyder (2019) |

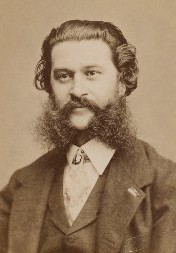

Johann Strauss II, Tritsch-Tratsch-Polka and The Blue Danube

In 19th-century Vienna, Johann Strauss II (1825- 1899) was known as “The Waltz King.” His dance- inspired compositions were enormously popular, and by the time of his death he had accumulated countless honors and plaudits. Strauss’s music is also uniquely tied to Viennese identity: It is played by the Vienna Philharmonic every New Year’s Eve and presented on nightly concerts for the benefit of tourists to the city. In total, Strass composed over 400 waltzes, polkas, and quadrilles. Although his orchestra did sometimes play for balls, Strauss’s fame and influence resulted from concert performances, and many of his compositions are not suited to dancing.

Strauss’s Career

Strauss carried on the legacy of his father, Johann Strauss I (1804-1849), who was largely responsible for transforming the waltz from a rustic country dance into a dance for the sophisticated urban ballroom. Johann I, however, forbade his sons from pursuing careers in music. He knew from experience that a musician’s life was strenuous, and he wanted stable, middle-class business careers for his own children. When he caught Johann II practicing the violin one day, therefore, he beat him severely. Johann II, however, was not to be deterred. Throughout his youth he secretly studied violin and composition with members of his father’s orchestra, and in 1844 he assembled his own orchestra and put on a concert at Dommayer’s Casino (a venue in which his father had frequently appeared, but that he subsequently boycotted).

The concert, which included popular selections of the day in addition to four of Strauss’s own compositions, was a great success, but the young orchestra leader still found it diffi- cult to compete with his father. He spent much of the first few years of his career touring outside of Vienna, and was only able to build his local reputation following his father’s death. Soon, however, Strauss had established himself as a musical trend-setter in the city, and in 1863 he was finally appointed Music Director of the Royal Court Balls—a position that had in fact been created for his father, but which Strauss was long denied due to his support for the rebels during the 1848 Vienna Revolution.

We will consider two of Strauss’s most famous compositions: Tritsch-Tratsch- Polka (1858) and The Blue Danube (a waltz composed in 1866). Both of these works were created for concert performance. While it would be possible to dance to them, at least in part, each contains elements that are intended to appeal to the listener and that might even foil any attempt to dance.

Tritsch-Tratsch-Polka

Invention of the polka is traditionally attributed to a housemaid working in Czech- speaking Bohemia. According to legend, she attracted attention with a lively dance set to a regional folk song. Admirers asked her to teach it to them, and the dance quickly spread throughout the countryside. Whatever its origins, the polka was certainly a fixture in Prague ballrooms by 1837, and it was being danced in Vienna by 1839. Next to the waltz, the polka was certainly the most successful European ballroom dance of the 19th century. Within a few decades, it was being danced throughout central and western Europe, up north in the Netherlands and Russia, to the east in India, and in the New World, where it was popular from Mexico to the midwestern United States.

The term “polka” is believed to be derived from the Czech word for “half,” and therefore probably refers to the duple meter of polka music. The dance is performed by couples, who embrace while performing a distinctive step (evocative of tripping or galloping) as they whirl around the room. Dancers tend to bob up and down in time to the beat. The polka is always performed at a fast tempo, and it is one of the more energetic 19th-century ballroom dances.

Strauss composed his Tritsch-Tratsch-Polka for performance in Pavlovsk, Russia, where he had the honor of conducting the summer concert season at the Vauxhall Pavilion every year between 1856 and 1865. These performances often stimulated his creativity, and Strauss created some of his most memorable works for these concerts. In 1858, he was inspired to write a polka that captured the excitement and thrill of gossip—for which “Tritsch-Tratsch” (an equivalent to “chit chat”) was current Viennese slang.

|

Tritsch-Tratsch-Polka 13. Composer: Johann Strauss II. Performance: The City of Prague Philharmonic (2004) |

Tritsch-Tratsch-Polka is certainly full of energy. Its characteristic motif— heard right at the beginning—is a rapidly ascending octave. The melody is played primarily by high-pitched instruments, such as the violin and flute, while the tinkling triangle emphasizes the offbeats. The polka is in a ternary form (A B A), each section of which contains its own repeating melodies. The A section has an internal form of a b c a, while the B section has the form d d e d e d. In short, Strauss deploys an excellent balance of contrast and repetition. The polka starts with an exuberant trill and ends with a hilarious sequence of outbursts from the flutes, oboes, and brass. The regular duple pulse in a fast tempo is maintained throughout, with occasional emphasis from the snare drum or cymbals.

The many musical details of Tritsch-Tratsch-Polka make it worth listening to. If one is dancing, it is more difficult to appreciate Strauss’s clever and delightful orchestration. At the same time, this music is perfectly suitable for dancing— although in such a case the orchestra might choose to repeat the B and A sections one or two times more before playing Strauss’s remarkable ending. In this case, therefore, we have music that was created for the concert stage but that could also live in the ballroom with minimal adjustment.

The Blue Danube

The Blue Danube has additional features that tie it to concert performance. Before considering those, however, we need to consider the waltz as a ballroom dance. Like the polka, the waltz seems to have originated in the Bavarian countryside, although it is somewhat older, perhaps dating to the mid-18th century. When the waltz first entered urban ballrooms, it proved something of a shock: Never before had pairs of dancers held each other in such a close embrace. In older ballroom dances, such as the minuet, the dancers kept a respectful distance from one another, but when waltzing a man actually put his hand around his partner’s waist. Soon, however, dancers had become accustomed to this new style, and by the 1780s the waltz was common in Vienna and beginning to spread around Europe. It was Strauss himself, however, who—building on the legacy of his father—ensured the dance’s popularity throughout the 19th century.

|

Time |

Form |

What to listen for |

|

0’00” |

Intro |

Flutes and horns hint at the first waltz theme;tremolo strings shimmer in the background |

|

1’27” |

Waltz 1 |

Internal form: abb |

|

2’34” |

Waltz 2 |

Internal form: aaba |

| 3’34” | Waltz 3 | Internal form: aabb 4’33” Waltz 4 Internal form: intro aabb |

| 5’43” |

Waltz 5 |

Internal form: intro aab |

The waltz calls for smooth, gliding motions, and is therefore quite unlike the polka. A mid-19th century waltz was energetic but stately—the tempos, therefore, were moderate. The waltz is in a characteristic triple meter, with dancers moving down and forward on the first beat, but rising up on the second and third. This is reflected in the music, for the first beat (or downbeat) is usually stronger and sounded in a lower range than the others (often intoned as “boom-chuck- chuck”). In Vienna, it became typical for the orchestras play the second beat just a little early, thereby producing a sense of weightlessness in the last part of the pattern.

The Blue Danube actually began life as a choral piece. It was commissioned by the Vienna Men’s Choral Association, with whom Strauss had already enjoyed a two-decades-long association. While Strauss was supposed to be at work on his choral waltz, Austria suffered a bitter defeat in the Seven Weeks’ War with Prussia. The conflict sapped morale in Vienna, with the result that the choirmaster encouraged Strauss to write an exceptionally joyful and lighthearted piece in order to lift the audience members’ moods. A satirical text was added by the Choral Association poet, although it was apparently disliked by both the singers and the audience. As a result, the reception accorded The Blue Danube at its premiere on February 15, 1867, was surprisingly tepid for a waltz that would become Strauss’s most popular composition. A more serious text— that sometimes sung today—was appended in 1889. However, The Blue Danube is most often heard in its purely orchestral form, and it was as an instrumental piece that it became famous following a performance at the World Exhibition in Paris later in 1867.

Unlike Tritsch-Tratsch-Polka, The Blue Danube is a fairly lengthy piece with a complex form. Like Strauss’s other waltz-inspired concert pieces, it consists of a string of independent, self-contained waltzes—five, to be precise—preceded by an introduction and followed by a lengthy coda. The introduction hints at the theme of the first waltz, while the coda revisits themes from the first four waltzes, concluding with a grandiose statement of the same theme with which the piece timidly opened.

One could not dance to this version of The Blue Danube: The introduction starts too slowly and is too tentative, while the coda would confuse dancers with its unorthodox form and frequent transitions. The individual waltzes, however, could easily be extracted for ballroom use. Each is in binary form, the A and B sections of which each contain the correct sixteen measures and expected repeats. Although each of the waltzes contains two distinct themes, the standard waltz rhythm (“boom-chuck-chuck”) is never absent.