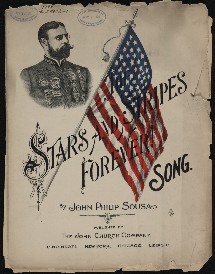

12.3: John Philip Sousa - “The Stars and Stripes Forever”

- Page ID

- 92078

The most prolific and influential composer of marches in the United States was John Philip Sousa (1854-1932). Although he began his career as a military musician, most of Sousa’s marches were intended for concert performance by his band, which toured the world for decades around the turn of the 20th century. For this reason, his marches are particularly interesting to listen to, but they still meet the requirements for functional marching music.

Sousa was born in Washington, D.C., where his father served as a trombone player in the Marine Band. Following some initial private music instruction, Sousa enlisted as a musical apprentice in the United States Marine Corps at the age of 13. He left the military in 1875 to pursue a career in theater music, and over the next five years he performed on the violin and began to develop his ability as a conductor. During this period, Sousa also became an expert arranger—a skill that would serve him well for the remainder of his career. At first he produced orchestrations of popular operas, but later he would make a name for himself as a composer. In 1880, Sousa was asked to produce a series of arrangements of operatic selections for the Marine Band. On the strength of his excellent work, he was invited to rejoin the Corps, this time as director of the Marine Band.

|

Time |

Form |

What to listen for |

|---|---|---|

|

0’00” |

Intro |

The march starts with a unison melody played by the ensemble |

| 0’04” | AA | variety of instruments play the melody 0’19” A The A strain is repeated |

| 0’34” | B |

The volume drops as the clarinets and euphoniums take the melody |

| 0’50” | B | The second pass through the B strain, featuring the trumpets, is considerably louder |

| 1’05” | C |

The volume diminishes again as single-reed instruments take the melody |

| 1’37” | D | Unison trombones lead off this passage |

| 2’01” | C’ |

A piccolo countermelody is added to the C strain 2’31” D The D strain is repeated |

| 2’55” | C’’ |

A trombone countermelody is added to the C strain; in addition, the trumpets take over the melody, thereby increasing the volume |

The United States Marine Band

The United States Marine Band has a remarkable history of its own. Established in 1798, it is the oldest of the formal United States military bands, which today number well over one hundred and are attached to all five branches of the military. Of course, the United States military employed musicians long before the Marine Band was formed—and indeed, long before the United States itself came into existence. As early as 1633, the Virginia militia relied on drummers to coordinate drills and maneuvers, and beginning in 1687 the Virginia colonists provided public funds for the purchase of military instruments. The first record of a complete military band dates from 1747, when the Pennsylvania colonists formed regiments.

Both drummers and bands supported American troops throughout the Revolution. In fact, musicians have been credited with some of the major victories. At the 1777 Battle of Bennington, for example, the drummers and fifers accompanied troops directly into battle, inspiring the soldiers to soundly defeat the British in what has since been recognized as a turning point in the war. That same year, buglers were added to cavalry units and tasked with coordinating maneuvers by means of bugle calls. At the conclusion of the war, General Washington proclaimed that all military musicians were to be allowed to keep their instruments in recognition of the great hardship they had endured.

The 19th century saw significant improvements both in military music programs and in the construction of the instruments used by military bands. As of 1815, when music was introduced to the West Point curriculum, a military band was likely to include flutes, oboes, bassoons, clarinets, French horns, serpents, bass drums, and tambourines. Soon, however, improved brass instruments— most notably the trumpet, which could now play complex melodies—led to their inclusion in the standard band line-up. These technical developments were the result of new production techniques associated with the Industrial Revolution, and they benefited wind musicians in all settings by greatly expanding the capabilities and ranges of their instruments.

By the time Sousa began his career, therefore, the military band was a large and sophisticated ensemble capable of great flexibility and nuance. Sousa himself aided in the creation of the sousaphone, which is essentially a tuba that has been modified to increase its capacity such that it can be heard over a band. The status of military musicians was also on the rise. General Phillip Sheridan had credited musicians with Union victories in the Civil War, stating that “music has done its share, and more than its share, in winning this war.” The Civil War was certainly fought to diverse musical accompaniment: 28,000 musicians serving in 618 bands accompanied troops into battle, played for ceremonies, and provided entertainment at military encampments.

Sousa’s Career

As director of the Marine Band, Sousa was primarily responsible for providing ceremonial music. Since 1801, the Marine Band has boasted a unique attachment to the White House, earning the nickname “The President’s Own.” The Marine Band plays for all Presidential inaugurations, state funerals, and military funerals at Arlington National Cemetery. It also marks the arrival of visiting heads of state and participates in state dinners and formal receptions. As the premier national music ensemble, it serves as a symbol of military and political might.

Sousa, however, also expanded the public-facing role of the Marine Band. In 1891 he took the band on a concert tour, inaugurating an annual tradition that has carried into the present day. Under Sousa, the Marine Band also released commercial recordings under the auspices of the Columbia Phonograph Company. This was a point of significant contention for Sousa himself. On the one hand, his Columbia recordings made him famous: It was as a direct result of his success as a recording artist that Sousa was able to launch a lucrative private career upon leaving the military in 1892. At the same time, Sousa believed that recording technology marked the inevitable decline of live music as both a professional and amateur pursuit.

For decades to come, Sousa would publicly resist the steady growth of the recording industry while simultaneously profiting from it. 1906 saw the publication of Sousa’s most famous attack on the industry, an article entitled “The Menace of Mechanical Music.” That same year he made the following remarks at a congressional hearing:

These talking machines are going to ruin the artistic development of music in this country. When I was a boy—I was born in this town—in front of every house in the summer evenings you would find young people together singing the songs of the day or the old songs. To-day you hear these infernal machines going night and day. We will not have a vocal cord left. The vocal cord will be eliminated by a process of evolution, as was the tail of man when he came from the ape.

Sousa conjured up an apocalyptic image of parlor pianos fallen silent and children divested of the ability to sing their childish songs. He warns of a future where all music will come from the “talking machine.” At the same time, however, Sousa’s own band was releasing recordings—although Sousa himself almost never conducted the ensemble at recording sessions and was able to proudly state that he was in no way personally associated with the gramophone companies.

Although this might seem hypocritical, the subject of the congressional hearing mentioned above—a new copyright law, intended to protect the rights of composers in the realm of recorded music—casts the controversy in a different light. While Sousa may indeed have genuinely feared the effects of “canned music” on amateur participatory music making, he was primarily concerned with the rights of composers, who were losing income due to that fact that they could not claim royalties on recordings of their works. Until 1909, anyone could make and sell unlimited recordings of a published musical composition or literary work upon purchasing a single copy of the printed product. Composers, lyricists, song writers, and authors were not entitled to royalties, and instead had to watch those in the recording industry get rich from their creative work. In making the above argument, Sousa was trying to appeal to the public and win support for the passage of updated legislation. He was eventually successful: The Copyright Act of 1909 guaranteed compensation to composers and authors whose work was reproduced in a recorded medium.

Sousa also worried that “canned music” would prevent people from attending live performances by the Sousa Band, for such concerts were the main source of income for Sousa and his musicians. The Sousa Band toured constantly, making visits not only to all parts of the United States but to countries around the world. In total, the band gave well over 15,000 concerts between 1892 and 1931. A typical concert would include transcriptions of popular orchestral works, operatic excerpts (complete with vocal soloists), virtuosic instrumental solos, and—most thrilling of all—newly-composed marches by Sousa himself.

The Stars and Stripes Forever

We will consider Sousa’s most famous march, “The Stars and Stripes Forever.” According to Sousa, he composed this march in his head in late 1896, shortly after hearing about the death of his manager and friend David Blakely. It was premiered in early 1897 and met with immediate success. Ninety years later, in 1987, “The Stars and Stripes Forever” was designated as the National March of the United States of America by an act of Congress.

In addition to performing “The Stars and Stripes Forever” at concerts, the Sousa Band made several recordings of the march. Even more profitable, however, were Sousa’s various arrangements for performance by amateur musicians. These included versions for piano (two, four, or six hands), zither (solo or duet), one or two mandolins (solo or with piano accompaniment), guitar (solo or duet), banjo (solo or duet), and banjo with piano. In addition, Sousa published full band arrangements for all of his marches—although he was careful to include many part duplications between the instruments, so that even a small town band with only a few members would be able to give a successful performance.

“The Stars and Stripes Forever” provides a typical example of a Sousa march. Its form might be summarized as: intro A A B B C D C’ D C’’. It begins with a brief but loud introduction by the whole band. This is followed by three distinctive melodic passages, or “strains,” the first two of which (A and B) are repeated. Each of the strains is in the major mode, and each—naturally—features the regular pulse of percussion and low brass. Next, an interlude (D) interrupts the pleasant mood of the strains: Blasting brass belt out chromatic scales and dissonant chords, exploring minor-mode territory while climbing to successively higher pitch levels. It is a relief, therefore, when the third strain returns (C’), now with a piccolo countermelody floating over the topic. Another interlude (D) sets up a final rendition of the C strain. Now elaborated upon even further, C’’ features both the piccolo countermelody and an additional countermelody in the trombones. The resulting cacophony is undeniably exciting.