9.4: Germany- “The Song of the Germans”

- Page ID

- 90730

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

While “The Star-Spangled Banner” traced a long path to its status as national anthem, the process was fairly straightforward. The same cannot be said of many other countries. The current national anthem of Germany is titled “The Song of the Germans” (German: Das Lied der Deutschen). However, it was not the first national anthem, and it has not been in continuous use. Its history offers an excellent example of how transformations in the identity, contents, and use of an anthem can reflect the complex political journey of an individual nation.

Although it traces its history back for many centuries, the modern nation of Germany came into existence in 1871. By this time, it was typical for European nations to adopt national anthems, and the Germans were certainly not to be excluded from this practice. At first, they adopted the Prussian national anthem. They did so to symbolize the unification of previously- independent Prussian principalities under a single nation. The title of the anthem was “Hail to Thee in the Victor’s Crown,” and it featured the refrain “Hail to thee, emperor!” The melody, however, was that to which “God Save the Queen” is currently sung—a sign of the close ties between European monarchies.

World War I, in which Germany was defeated, prompted major political reorga- nization. The emperor abdicated in 1918 and was replaced by a constitutional government known as the Weimar Republic. The new government required a new anthem—but the song selected for the role was in fact very old. The words to “The Song of the Germans” were written in 1841 by August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben, a Prussian academic. The text was initially subversive. Fallersleben lived and worked in a monarchy, but his song called for the unification of the German-speaking lands under democratic rule. During his own time, this was a dangerous message, and Fallersleben was dismissed from his post for promoting it. Following the unification of Germany, however, the call became patriotic and Fallersleben’s song was celebrated.

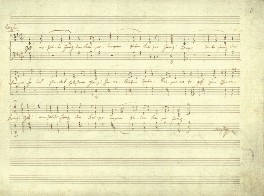

Like Key, Fallersleben wrote his text to fit a preexisting melody. Because he was making a political plea, he selected a political tune: the national anthem of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which carried a text entitled “God Save Emperor Francis.” By rewriting this important anthem, Fallersleben sought to rewrite political reality. The tune, incidentally, had been composed in 1797 by one of the most important of all Austrian composers, Franz Joseph Haydn. It would continue to serve as the national anthem of Austria, although with different texts to suit changes in government, until World War II.

World War II also brought changes to Germany, which was divided at the close of the war into East Germany and West Germany. The government of East Germany commissioned an entirely new anthem, entitled “Risen from the Ruins,” while West Germany ceased to use an anthem altogether. Although unusual, it is not difficult to explain this development. Anthems tend to represent patriotic feeling and pride in one’s country—sentiments that seemed inappropriate in a post- Holocaust Germany. Various songs— including Ludwig van Beethoven’s

Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” is the official anthem of the European Union. Here it has been recorded with the original German text, but it is also sung in other languages and performed as a textless instrumental.

“Ode to Joy,”2 now the anthem of the European Union—were used to mark state occasions in West Germany, but “The Song of the Germans” was not officially readopted until 1952.

When it did enter back into use, it was accompanied by significant conflict over the text. The first stanza in particular had become controversial. It opens with the line, “Germany, Germany above all, above all in the world.” To Fallersleben, this meant that the promise of a united German nation must be held above the petty interests of minor German monarchs. To the Nazis, however, it was a call for Germany to take over the world. The second verse, which celebrates German women, wine, and song, perhaps lacks the dignity required of an anthem. After the war, therefore, the third verse was favored:

Unity and justice and freedom For the German fatherland!

Towards these let us all strive Brotherly with heart and hand! Unity and justice and freedom Are the safeguards of fortune;

Flourish in the radiance of this fortune, Flourish, German fatherland!

Controversy over the words, however, has come to stand in for larger political battles. In this way, “The Song of the Germans” simultaneously unites and divides the country, while embodying its difficult past.

Performing “The Song of the Germans”

To consider “The Song of the Germans”3 in use, we will look at a performance that is, in most respects, very similar to Houston’s rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” This performance also took place at a major sporting event—a match between two teams in the national German soccer league. The anthem was again sung by a popular performer. Namika, who was born Hanan Hamdi to Moroccan immigrant parents, is a well-known singer and rapper who has landed several hits since 2015. Like Houston, she performs the anthem in her own individual style. She introduces melodic ornaments but makes a conscious effort not to distract from the dignity of the text. And, finally, the orchestration of the accompaniment is remarkably similar, for Namika is also backed by the militaristic combination of brass and snare drums, and her rendition is likewise punctuated by trumpet fanfares.

|

“The Song of the Germans” Composer: Franz Joseph Haydn 3. Lyricist: August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben Performance: Namika at Bundesliga match between FC Bayern Muenchen and Bayer 04 Leverkusen in Munich (2017) |

There is, however, one very significant difference: Namika is joined by the fans, whose voices can clearly be heard throughout the performance. While Houston was admired as a soloist, Namika is leading a sing-along. Why this difference? It is certainly not the case that Germans are more patriotic or more musical. The German anthem, however, is considerably more singable than “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Given that it outlines a range of only an octave and that the melody is largely conjunct, containing few large melodic leaps, “The Song of the Germans” can be sung by an untrained musician. It is likely that these musical differences have contributed to contrasting cultural traditions: Germans join in, while American leave anthem singing up to the professionals.