5.2.2: Franz Schubert - The Lovely Maid of the Mill

- Page ID

- 90706

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Franz Schubert (1797-1828) lived a quiet life in Vienna, where he wrote over 600 songs for performance at intimate domestic gatherings. Although he died young, and without achieving significant fame outside of Vienna, his work became widely-known in the mid-19th century and today he is considered to be one of the finest composers of the era.

Song and National Character

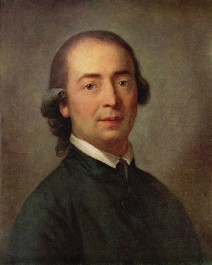

Before we can look at Schubert’s songs, we need to know something about the cultural context in which he was working. In the early 19th century, new ideas about national identity were in the air. Many of these ideas were rooted in the work of German philosopher Johann Gottfried von Herder, who argued that spoken language influenced an individual’s character. He suggested, for example, that Germans all thought in roughly the same way because they spoke the same language, which in turn guided and structured their intellectual activity. From here, the notion that people who spoke the same language should participate in bounded, self-governing communities—nations, in fact—was not far removed.

During Schubert’s time, neither Germany nor Austria existed in anything resembling their present forms, but the idea that communities of people who spoke a common language should constitute autonomous nations was quickly taking hold.

Herder also believed that the most authentic form of national character was to be found among those least corrupted by cosmopolitan influences—the peasants who worked the land. Before the late 18th century, impoverished rural folk were treated with contempt. It was not believed that they had anything to offer the ruling classes other than labor. Following Herder, however, they became the one true source of authentic “folk” culture, and therefore key to a nation’s ability to understand itself.

Collectors began to scour the countryside for folk stories, folk poetry, folk dances, and folk songs. These were compiled and published for popular consumption. Perhaps the most famous of such collectors were the Brothers Grimm (Jacob Ludwig Karl and Wilhelm Carl), who were responsible for first recording many of the fairy tales—including Cinderella, Hansel and Gretel, Snow White, Rapunzel, and Sleeping Beauty—that have been ceaselessly told and retold around the world ever since.

All of this is important to our discussion of Schubert for two reasons. First, the elevation of the German language meant that German songs had the potential to become art. Before Schubert’s time, songs were regarded as trivial popular entertainment. Schubert’s songs, however, were taken seriously as cultural expression of the highest order.

Second, general fascination with folk culture and art influenced Schubert’s approach to writing songs. He often chose texts that imitated folk poetry, or at least dwelt on rural subject matter, and he frequently set these to music in a folk-like style. Although some of his music seems very simple, Schubert did not resort to the folk idiom because he lacked ability or imagination. Instead, he imitated genuine folk song to augment his storytelling.

We will see all of this influence at work in Schubert’s 1824 song cycle The Lovely Maid of the Mill. Before turning to the story and music, however, we need to consider the setting in which the music was meant to be experienced.

Salon Culture

In the Vienna of Schubert’s time, music lovers supported an economy of small, in-home concerts known as salons. A salon might be hosted by a wealthy family for the purpose of advertising their cultural and social capital. The performance would take place in the family’s living room, where visitors could admire their furnishings and art. Hosting a salon was also considerably cheaper than maintaining a private orchestra, so it became the preferred means of cultural expression as Vienna’s wealth slowly shifted from a small group of aristocrats to a larger middle class.

Naturally, certain types of music were preferable for salon entertainment. Only a few performers could fit in the venue at a time, and loud instruments were not welcome. A great demand arose, therefore, for solo piano music, chamber music (two to five individuals each playing their own part), and song, all of which Schubert produced in enormous quantities.

All of Schubert’s songs and chamber music were conceived of with this sort of environment in mind. In fact, he became so prominent in the salon scene that a special term, Schubertiade, was developed to describe a salon performance that featured only his music. Salons were comparatively informal, and listeners would gather around the performers in close proximity. Paintings of salon performances show listeners in rapt attention.

This type of engagement with music was typical more generally of Schubert’s era, when the public held art in high regard and believed that artists were in a position to communicate profound truths. Schubert’s listeners sought not only entertainment but also enlightenment, transformation, and catharsis. The Lovely Maid of the Mill offered all.

“Wandering”

The first song is entitled “Wandering.”

The poem reads as follows:

Wandering is the miller’s joy, Wandering!

A man isn’t much of a miller,

If he doesn’t think of wandering, Wandering!

We learned it from the stream, The stream!

It doesn’t rest by day or night, And only thinks of wandering, The stream!

We also see it in the mill wheels, The mill wheels!

They’d rather not stand still at all and don’t tire of turning all day, the mill wheels!

Even the millstones, as heavy as they are, The millstones!

They take part in the merry dance And would go faster if they could, The millstones!

Oh wandering, wandering, my passion, Oh wandering!

Master and Mistress Miller,

Give me your leave to go in peace, And wander!

translated by Celia Sgroi

|

“Wandering” from The Lovely Maid of the Mill. Composer: Franz Schubert. Performance: Ian Bostridge and Mitsuko Uchida (2005) |

The textual contents, frequent word repetition, and generous use of exclamation points all paint a picture of an enthusiastic (if naive) young man. His outlook is positive and he sees nothing but joy in his future. He also indicates a clear preference for individual liberty. He is not, in other words, the type of young man who is eager to take on the responsibilities of marriage.

Schubert translates all of this enthusiasm and simplistic good nature into his music. He seems to imagine the miller’s words as constituting a folk-type song, which the young man literally sings as he walks through the woods. To do so, Schubert keeps his setting (the music crafted to suit a set of words) very simple. To begin with, he creates a strophic song, in which each stanza of the text is set to the same music. As a result, we hear the same melody and accompaniment five times in a row. This is a standard form for European and American folk music, which is traditionally learned by ear and memorized. One can easily master the melody, which can then be used to sing a limitless amount of text. This form is also common in the Christian hymn tradition. In all of these cases, the focus is meant to be on the meaning of the words.

Schubert’s strophic melody is simple and catchy. The opening melodic phrase is heard twice, as is the last, while the middle section presents an additional melody in sequence (that is to say, it is repeated at a different pitch level—lower, in this case). In total, therefore, this song contains three short melodic ideas, all of which are repeated either verbatim or with a minor alteration.

Schubert’s melody, however, does not quite imitate a folk song. It is in fact fairly challenging to sing, as it contains a number of difficult leaps in the first and third sections. His piano accompaniment also walks the line between simple and sophisticated. It utilizes a straightforward pattern of arpeggiated harmonies (a technique by which the notes in a triad are played from lowest to highest and/or vice versa), none of which challenge the ear, but it is denser and more varied than one would expect in the folk tradition.

Over the course of the song cycle, however, the listener comes to realize that the piano does more than just support the singer. Schubert encourages us to hear the piano as a second storyteller. Perhaps its arpeggiated accompaniments, which are present in almost every song, represents the gurgling of the brook. When the arpeggiations are absent, it is always for a significant reason. The brook itself turns out to be a very important character. In addition to being present in many of the texts, it actually becomes the narrator for the final poem. We don’t know any of this when we first hear the opening song, but in retrospect we must think twice about what the piano has to contribute.

“Mine!”

The eleventh song in the cycle is entitled “Mine!” This song marks the moment when the miller wins the heart of the girl (or so he thinks). The poem expresses his exuberance:

Brook, stop your murmuring! Wheels, stop your thundering! All you merry woodland birds,

Large and small, Stop your singing! Through the grove, In and out,

Only one phrase resounds:

The beloved miller’s daughter is mine! Mine!

Spring, are these all your flowers? Sun, can’t you shine any brighter? Alas, then I must stand all alone, With the blissful word mine, Misunderstood in this vast universe.

translated by Celia Sgroi

Schubert brings this text to life with equally joyful music. He sets a brisk tempo, and the singer rushes through the words with a sense of youthful excitement. This is most certainly not a folk song. To begin with, it is not strophic, but through- composed—a term used to indicate a song that pairs a unique melody with each line of poetic text instead of repeating the same melody.

|

Time |

Form |

What to listen for |

|---|---|---|

|

0’00” |

Piano introduction |

The arpeggios in the left hand of the accompaniment suggest the steady murmuring of the brook |

|

A |

||

|

0’10” |

“Brook, stop your murmuring!” . . . |

A melodic motif is repeated at progressively higher pitch levels |

|

0’28” |

“Through the grove” . . . |

Repetition of another motif culminates in the singer’s repetition of the word “mine” on a loud, high note |

|

0’49” |

Transition |

The music shifts to a new key (B flat major) |

|

0’53” |

B “Spring, are these all your flowers?” |

This section, which rests briefly on a minor- mode harmony, seems more disturbed than the A section |

|

1’19” |

Transition |

The music returns to the original key (D major) |

|

1’24” |

A |

The A text and music return |

|

2’01” |

Coda |

The singer repeats the word “mine;” the pianist provides a concluding passage |

This song is also too complex to be perceived as a folk product. Schubert uses a ternary form (A B A), in which the first ten lines of poetry and their accompanying music constitute the A section and are therefore heard at the beginning and end of the song. The A section begins with another sequence. This time, a melodic fragment is heard at higher and higher pitch levels—an indication of the speaker’s excitement. The A section ends with a rapid passage of notes that rocket to the highest pitch on the word “Mine!” The B section, apart from having a unique character, is in a different key than the A section (B-flat major instead of D major). This gives the song an added sense of wonder and delight. The piano accompaniment provides gurgling arpeggiated harmonies throughout.

“Withered Flowers”

Next we will visit the eighteenth song, entitled “Withered Flowers.” At this point, the miller has passed through various stages of suspicion and anger, and he has nearly resigned himself to his tragic fate:

All you flowers

That she gave to me, They should put you With me in my grave.

Why do you all look at me So sorrowfully,

As if you knew,

What was happening to me?

All you flowers,

Why so limp, why so pale? All you flowers,

What has drenched you so?

Ah, but tears don’t bring The green of May,

Don’t cause dead love To bloom again.

And spring will come, And winter will go, And flowers will

Grow in the grass again.

And flowers are lying In my grave,

All the flowers

That she gave to me.

And when she strolls Past my burial place And thinks to herself:

He was true to me!

Then all you flowers Come out, come out! May has come,

And winter is gone.

translated by Celia Sgroi

The poem begins in a mournful, self-pitying vein, but the final stanzas introduce a glimmer of hope. The miller imagines a future time when his beloved, passing by his grave, will regret her cruelty. He will be dead, of course, but he will also be vindicated. The form of this poem—a series of eight stanzas—suggests a strophic setting, but Schubert provides something quite different. He sets the first three stanzas to a slow, minor-mode melody that expresses their tragic sentiment. Then he repeats that melody for the next three stanzas. For the final two stanzas, however, he shifts to the relative major (that is to say, he moves from E minor to E major) and introduces a new melody, all of which is repeated for emphasis. At the climactic phrase “May has come,” the singer soars to the highest notes in his range, and the vocal music concludes on a definitively triumphant note.

|

Time |

Form |

What to listen for |

|---|---|---|

|

0’00” |

A “All the flowers” . . . |

The piano accompaniment is sparse and restrained |

| 1’08” | A’ | “Ah, but The music in this passage is identical to that of tears don’t the first A section bring” . . |

| 2’09” | B | “And when piano accompaniment becomes more active she strolls” |

| 2’44” | B |

The mode changes from minor to major and the The text and music of the B section are repeated |

| 3’18” | B “Then all yet again your flowers” | The closing passage of the B section is repeated |

| 3’34” | Coda | The piano accompaniment transitions back to minor as it moves into the lowest range of the instrument |

Once again, however, we would be remiss to ignore the piano accompaniment, which is particularly striking in this example. After seventeen songs in which the piano has sparkled and bubbled, now it has suddenly gone dead. We hear only dry, sparse chords for most of the song. This accompaniment reinforces the sorrowful mood of the miller, who has given up hope. The piano comes back to life with the final two stanzas, and builds in strength as the miller gains confidence. However, the piano also foreshadows the conclusion to this story, which will not be a happy one. Although the singer ends on a triumphant, major-mode cadence, the closing passage into the piano returns to E minor as it fades away and moves into the lower ranges of the instrument. The careful listener knows that the miller’s hope is false.

“The Brook’s Lullaby”

The final song in the cycle is entitled “The Brook’s Lullaby.”5 The narrator is no longer the miller, who has drowned himself, but rather the brook, which promises to protect the disappointed lover and see that no more harm comes to him:

Rest well, rest well!

Close your eyes.

Wanderer, you weary one, you are at home. Fidelity is here,

You’ll lie with me

Until the sea drains the brook dry.

I’ll make you a cool bed On a soft cushion

In your blue crystalline chamber. Come closer, come here, Whatever can soothe,

Lull and rock my boy to sleep.

If a hunting horn sounds From the green forest,

I’ll rumble and thunder all around you. Don’t look in here

You blue flowers!

You trouble my sleeper’s dreams.

Go away, depart From the mill bridge,

Wicked girl, so your shadow won’t wake him! Throw in to me

Your fine scarf,

So I can cover his eyes.

Good night, good night, Until everything wakes.

Sleep away your joy, sleep away your pain. The full moon rises,

The mist departs,

And the sky above, how vast it is!

translated by Celia Sgroi

|

“The Brook’s Lullaby” from The Lovely Maid of the Mill. Composer: Franz Schubert. Performance: Ian Bostridge and Mitsuko Uchida (2005) |

For this final song, Schubert again provides a strophic setting, full of repeating melodic fragments. This time, however, he is imitating not a folk song but a lullaby. The melody is gentle and calming. It consists mostly of stepwise motion, and it is free of dramatic leaps and exciting runs. It almost sounds like a real lullaby, but not quite. Once again, Schubert makes things a bit too complicated by moving from E major to A major for the middle section, and by introducing a flatted pitch near the end that suggest E minor. The result is a particularly passionate lullaby with a hint of sadness.