4.3.2: Javanese Traditional - The Love Dance of Klana Sewandana

- Page ID

- 92116

Like sung drama, danced drama can be found around the world. Some of the richest traditions hail from Southeast Asia, where one can find dozens of distinct varieties of danced storytelling. Our example belongs to the wayang wong tradition, which developed in the courts of central Java, an island that is now part of Indonesia. Although wayang wong is unique to this small region, many of its musical and dramatic elements can be found across Java and throughout Indonesia. The most important of these is gamelan music, which is played on pitched gongs and keyed metallophones (marimba and xylophone are Western examples of such instruments).

Indonesia as Kingdom and Colony

Indonesia’s performing arts traditions reflect its diverse cultural heritage. Civilization on the islands dates back thousands of years. Indonesia was at first ruled over by a series of Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms, but the arrival of Islam in the 15th century resulted in the gradual conversion of the population. Today, Indonesia is the largest Muslim nation in the world, although many inhabitants practice a form of the religion that contains traces of the region’s Hindu and Buddhist heritage.

Javanese music is well known in the West due to the island’s colonial history. Dutch traders began to visit the Indonesian islands in the 16th century. The profitability of trade led to an influx of Dutch settlers, who established a local government under the auspices of the United East India Company. When the company failed in 1800, the Dutch government formally annexed the Dutch East Indies—which included most of Java—as a colony. Under Dutch rule, indigenous courts were allowed to remain intact, but they were granted only ceremonial powers. While this denied Indonesians their political autonomy, it contributed to the flourishing of Indonesian art, which the Dutch encouraged. It also facilitated the spread of Javanese music and art to Europe.

During World War II, Indonesia was occupied by the Japanese, who drove out the Dutch in an attempt to claim the islands for themselves. At the conclusion of the war, the Indonesians proclaimed independence. The Netherlands attempted to reassert its claim to the territory by force, and a military conflict ensued. In 1949, however, facing intense pressure from other powers, the Dutch acknowledged Indonesia as an independent nation. The impact of Dutch colonialism on the spread of Javanese cultural products resonates into the present day, and gamelan music in particular can be heard throughout the world. Indeed, there are over one hundred gamelan ensembles in the United States alone.

Wayang Wong

The dance form we will explore here, wayang wong, developed during the colonial era and resulted from the conflict between indigenous and colonial powers. Wayang wong was created at the court of Hamengkubuwono I, the first Sultan of Yogyakarta. Hamengkubuwono was to inherit the throne of the Mataram Sultanate from his brother, Pakubuwono II, but instead led his followers in a civil war after Pakubuwono agreed to cooperate with the United East India Company. The war ended in 1755 with a treaty establishing courts at Yogyakarta and Surakarta. Although this was nominally a victory for Hamengkubuwono, the Dutch ultimately benefited by pitting the courts against one another over the next two centuries. All the same, Yogyakarta remained a stronghold of Javanese resistance, and today serves as the capital of an independent region of the same name.

Wayang wong was initially conceived of as a decadent three-day spectacle celebrating and affirming the power of the newly-established Yogyakarta court. Although the first performance required dozens of dancers and lasted from dawn to dusk on each of the days, it has persisted in scaled-down forms. The term wayang wong literally means “human wayang.” This is in deference to the principal form of Indonesian theater, wayang kulit, which uses shadow puppets to act out traditional epics to the accompaniment of music.

All forms of wayang tell stories that have a long history in Indonesian culture. The principal sources are two Indian epics, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. Wayang performances also draw from the Panji stories, which concern the life of a legendary Javanese prince. Each of these epics is much too long and complex to be related in a single performance. Instead, wayang performers select individual stories, which they often elaborate in ways that add novelty without disrupting the traditional narrative. Indonesian audiences are already familiar with the stories, and they appreciate seeing the characters and events presented with originality.

Gamelan

Our example presents an excerpt from the Panji stories, which we will consider in greater detail below. Before that, however, we owe some attention to the music that accompanies wayang wong dance. The instruments used in gamelan music date back to at least the 8th century, although they did not acquire their present form until the 15th or 16th century, when gamelan music became an important component of court life. Gamelan music is ubiquitous in traditional Indonesian culture. It can be performed on its own, but it is also used to accompany dance and theater. It is played for court celebrations and religious ceremonies, pursued by amateurs for their own enjoyment, and consumed by fans as entertainment.

A gamelan is a collection of bronze percussion instruments that are struck using a variety of mallets. The components of a gamelan include vertically-hung gongs of various sizes, smaller gongs suspended horizontally in wooden frames, and melodic instruments consisting of metal bars suspended over resonating chambers. The instruments of a gamelan are built together and they remain together. It is not possible for players to bring their own instruments, or for an instrument to be substituted. This is because there is no fixed pitch system in Indonesian music, so gamelan instruments are tuned to one another by the original builder. Every gamelan therefore plays a distinct set of pitches.

In addition to being communally stored and maintained, gamelans are bestowed with names. This not only recognizes the gamelan’s status as a complete ensemble but also signifies the traditional belief that a gamelan possesses a spirit. This spirit resides primarily in the largest suspended gong, the gong ageng, which might be provided offerings of food, flowers, and incense. The blacksmith who forges the bronze components of the gamelan instruments is traditionally understood to hold special powers, and he is expected to prepare for his task through fasting and self-purification. His carefully-tuned gongs and bars are then set in ornately-carved wooden frames.

Each instrument in a gamelan occupies a specific place in the musical texture. The vertically- and horizontally-suspended gongs are all used to mark the pulses of the rhythmic cycles that underlie gamelan music. These cycles, each of which is named, consist of patterns of timbres provided by the various gongs. The gong ageng always marks the end of the cycle, which repeats throughout a performance and provides the structure.

The other bronze instruments—which include two sizes of bonang, gendèr, slenthem (an instrument that resembles the gendèr but is pitched lower and has fewer keys), and two sizes of saron— play the same melody in heterophonic texture. However, each of these instruments interprets the melody in a markedly different way. Some play ornate versions, some play spare versions, and some play syncopated versions. The result is a complex texture woven out of the brilliant and resonant timbres of the many instruments.

Gamelan music also uses a few additional instruments, although these are not part of the main gamelan ensemble. Such instruments usually provide improvised melodies that follow the contour of the main melody but are otherwise independent. The instruments that might fill this role include the rebab (a bowed fiddle related to the Chinese jinghu), the gambang (a wood-keyed xylophone), and the suling (a type of flute). Finally, a male choir or female soloist might sing, drawing their texts from a body of poems and riddles that belong to the gamelan tradition. These texts, however, are not associated with any particular musical composition. Instead, they might be heard in a variety of contexts.

A gamelan performance is led by the drummer, who plays three different sizes of a drum known as kendhang. The drummer starts and stops performances, but his most important task is to control the pace and to signal the dramatic shifts in tempo that are characteristic of gamelan music. During performance, the ensemble will periodically slow to half of its former tempo or accelerate to twice the tempo. This is accompanied by changes in how the melody is interpreted by each of the instruments, which will add notes at slow tempos in order to maintain a consistent texture.

The Love Dance of Klana Sewandana

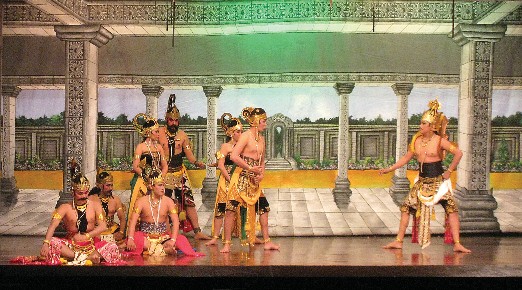

We are now prepared to turn to our example: A wayang wong performance that presents an episode from the Panji legends. Wayang wong is practiced both in masked and unmasked versions. This is obviously an example of the former. The use of masks in Indonesian dance dates back thousands of years. The masks are symbolically significant, and their shape, color, and details carry information about the character.

Many episodes of the Panji legend concern his romantic relationship with Sekartaji, who often finds herself separated from the Prince due to the intervention of malevolent forces. To survive, she frequently disguises herself as a man, at one point becoming the King of Bali and meeting Prince Panji on the battlefield. (There is also a long history of cross dressing in wayang dance itself.) The scene we will examine opens on Sekartaji alone in the forest. She has fled from the unwanted affections of King Klana Sewandana, whose obsession with her has driven him insane. Klana Sewandana attempts to seduce Sekartaji, but she rebuffs his advances. Luckily, Prince Panji has been drawn to the scene by his great love for Sekartaji. He fights and defeats Klana Sewandana, and the lovers are reunited.

| Time | Form |

What to listen for |

|---|---|---|

| 32’14” |

A few of the metallophones play a slow, Sekartaji alone in simple melody; the rebab and solo the forest female singer improvise high melodies; a percussionist taps rhythms on a wooden box |

|

| 35’12” | Klana Sewandana |

The music at first becomes faster and more enters and rhythmically intense; this is followed by attempts to fluctuations in tempo and dynamic seduce Sekartaji |

| 36’08 | A male solo singer enters and the rhythm becomes more regular | |

| 37’52 | The brighter/louder metallophones reenter | Prince Panji arrives and fights Klana the texture Sewandana |

| 38’21” | The male choir enters and most of the instruments drop out | |

| 39’06” | The rebab enters | |

| 39’35” | The solo female singer joins the male choir Instruments and singers continue to [...] leave and reenter the texture as the music fluctuates in intensity | |

| 45’30 | Prince Panji and Sekartaji are The music slows in tempo, then accelerates reunited | |

| 48’19 | The music slows in anticipation of the final note |

The three dancers in the scene move differently, for they represent the three character types of wayang wong. As a female type, Sekartaji keeps her feet close to the ground while executing refined movements with her hands, neck, and head. Klana Sewandana is a strong male, as betrayed by his wide stance, large steps, and aggressive movements. Prince Panji, on the other hand, is a refined male. As such, he keeps his feet close to the ground and moves fluidly.

Throughout the episode, the gamelan provides a constant musical backdrop while accentuating the dramatic contour. Klana Sewandana’s arrival in the forest, for example, is marked by an intensification of the music, which grows in volume and increases in tempo. Musical outbursts punctuate the fight scene, while a musical calm descends on the final scene between Panji and Sekartaji. From time to time we hear the rebab, the suling, and various singers, who can be seen seated behind the dancers. The words they are singing have nothing in particular to do with the drama unfolding onstage, but voices contribute an important aesthetic element to any performance.