1.1: Melody

- Page ID

- 72346

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction

Melody is a timely arranged linear sequence of pitched sounds that the listener perceives as a single entity.

Melody is one of the most basic elements of music. A note is a sound with a particular pitch and duration. String a series of notes together, one after the other, and you have a melody. But the melody of a piece of music isn’t just any string of notes. It’s the notes that catch your ear as you listen; the line that sounds most important is the melody. First of all, a melodic line of a piece of music is a succession of notes that make up a melody. Extra notes, such as trills and slides, that are not part of the main melodic line but are added to the melody either by the composer or the performer to make the melody more complex and interesting are called ornaments or embellishments.

Melody from Anton Webern‘s Variations for orchestra, Op. 30 https://youtu.be/AAQdEMYTdE

There are some common terms used in discussions of melody that you may find it useful to know. Below are some more concepts that are associated with melody.

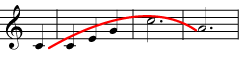

The Shape or Contour of a Melody

A melody that stays on the same pitch gets boring pretty quickly. As the melody progresses, the pitches may go up or down slowly or quickly. One can picture a line that goes up steeply when the melody suddenly jumps to a much higher note, or that goes down slowly when the melody gently falls. Such a line gives the contour or shape of the melodic line. You can often get a good idea of the shape of this line by looking at the melody as it is written on the staff, but you can also hear it as you listen to the music.

You can also describe the shape of a melody verbally. For example, you can speak of a “rising melody” or of an “arch-shaped”phrase.

Composer Richard Strauss’s Don Juan is a good example of ascending melody:

Melodic Motion

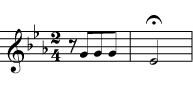

Another set of useful terms describe how quickly a melody goes up and down. A melody that rises and falls slowly, with only small pitch changes between one note and the next, is conjunct. One may also speak of such a melody in terms of step-wise or scalar motion, since most of the intervals in the melody are half or whole steps or are part of a scale.

A melody that rises and falls quickly, with large intervals between one note and the next, is a disjunct melody. One may also speak of “leaps” in the melody. Many melodies are a mixture of conjunct and disjunct motion. A melody may show conjunct motion, with small changes in pitch from one note to the next, or disjunct motion, with large leaps. Many melodies are an interesting, fairly balanced mixture of conjunct and disjunct motion.

Start listening at the 2:30 mark to Beethoven, “Ode to Joy” from Symphony No. 9 and note how the pitch rises and falls slowly, creating conjunct melody.

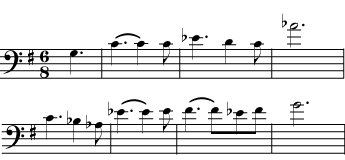

Melodic Range

Range refers to the distance between the highest and lowest notes found in a given melody. When a piece of music has wide range, there is a great distance between the highest and lowest pitches heard. Conversely, when a piece of music has narrow range the distance between the highest and lowest pitches is relatively small.

Wide Range

Narrow Range

As you listen to Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 5, in D Major, 1st Movement, note that the piece has a wide range in pitch.

Now listen to Brahms, Violin Concerto in D, 3rd movement, and note that it’s range is narrow compared to the Brandenburg Concerto.

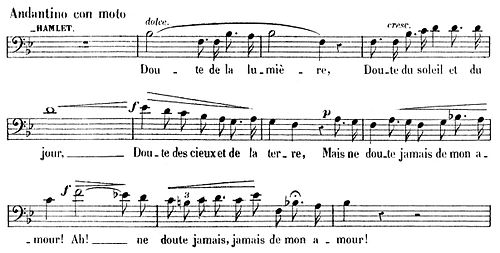

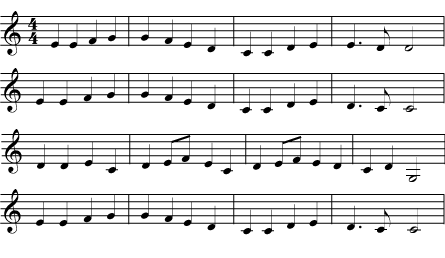

Melodic Phrases

Melodies are often described as being made up of phrases. A musical phrase is actually a lot like a grammatical phrase. A phrase in a sentence (for example, “into the deep, dark forest” or “under that heavy book”) is a group of words that make sense together and express a definite idea, but the phrase is not a complete sentence by itself. A melodic phrase is a group of notes that make sense together and express a definite melodic “idea”, but it takes more than one phrase to make a complete melody.

How do you spot a phrase in a melody? Just as you often pause between the different sections in a sentence (for example, when you say, “wherever you go, there you are”), the melody usually pauses slightly at the end of each phrase. In vocal music, the musical phrases tend to follow the phrases and sentences of the text. For example, listen to the phrases in the melody of “The Riddle Song” and see how they line up with the four sentences in the song.

But even without text, the phrases in a melody can be very clear as the notes are still grouped into melodic “ideas.”

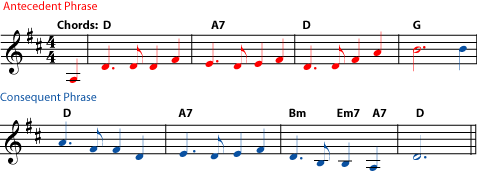

One way that a composer keeps a piece of music interesting is by varying how strongly the end of each phrase sounds like “the end”. By varying aspects of the melody, the rhythm, and the harmony, the composer gives the ends of the other phrases stronger or weaker “ending” feelings. Often, phrases come in definite pairs, with the first phrase feeling very unfinished until it is completed by the second phrase, as if the second phrase were answering a question asked by the first phrase. When phrases come in pairs like this, the first phrase is called the antecedent phrase, and the second is called the consequent phrase.The rhythm of the first two phrases of “Auld Lang Syne” is the same, but both the melody and the harmony lead the first phrase to feel unfinished until it is answered by the second phrase.

Antecedent and Consequent Phrases

Define the melody of this composition in terms of range, motion, and contour. J.S. Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto #6, first movement

Motive or Motif

Another term that usually refers to a piece of melody (although it can also refer to a rhythm or a chord progression) is motive or “motif”. A motive is a short musical idea – shorter than a phrase – that occurs often in a piece of music. A motive may only consist of a few pitches or maybe divided in smaller cells.

Most figures and motifs are shorter than phrases, but some of the leitmotifs of Wagner’s operas are long enough to be considered phrases. A leitmotif (whether it is a very short cell or a long phrase) is associated with a particular character, place, thing, or idea in the opera and may be heard whenever that character is on stage or that idea is an important part of the plot. As with other motifs, leitmotifs may be changed when they return. For example, the same melody may sound quite different depending on whether the character is in love, being heroic, or dying.

Themes

A longer melody that at times keeps reappearing in the music – for example, in a “theme and variations” – is often called a theme. Themes generally are at least one phrase long and often have several phrases. Many longer works of music, such as symphony movements, have more than one melodic theme.

The musical scores for movies and television contain themes, which can be developed as in a symphony or may be used very much like operatic leitmotifs. For example, in the music John Williams composed for the Star Wars movies, there are melodic themes that are associated with the main characters. These themes are often complete melodies with many phrases, but a single phrase can be taken from the melody and used as a motif. A single phrase of Ben Kenobi’s Theme, for example, can remind you of all the good things he stands for, even if he is not on the movie screen at the time.

Contributors and Attributions

- Melody. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Melody. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Understanding Basic Music Theory. Authored by: Catherine Schmidt-Jones. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/2ad74b7b-a72f-42a9-a31b-7e75542e54bd@3.74:20/Understanding_Basic_Music_Theo. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Blue Green Music Staff. Located at: https://pixabay.com/en/music-staff-blue-green-scrapbook-794506/. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved

- Richard Strauss: Don Juan / Gustavo Dudamel, conductor u00b7 Berliner Philharmoniker / Recorded at the Berlin Philharmonie, 2 February 2013.. Provided by: Berliner Philharmoniker. Located at: https://youtu.be/66zOdfCWEqA. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Handel: Joy to the World! (John Rutter and the Cambridge Singers). Authored by: Kate Price. Located at: https://youtu.be/wKW_az2HVfk?t=1s. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Dmitri Shostakovich - Romance (from The Gadfly). Authored by: Classical Music Only. Located at: https://youtu.be/QDW4VJGKLAQ. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube License