2.2: Elements of Creative Nonfiction

- Page ID

- 40374

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The main elements of creative nonfiction are setting, descriptive imagery, figurative language, plot, and character. The overarching element or requirement that distinguishes creative nonfiction from any other genre of writing is that while other literary genres can spring from the imagination, creative nonfiction is, by definition, true. As you complete the assigned readings in this chapter, keep track of the following elements as they arise in your readings: see if you can identify each of them. Learning these elements now will form a solid foundation for the rest of the class.

Setting

Each story has a setting. The setting is the place where the story takes place. Usually, an effective story establishes its setting early in the story: otherwise readers will have a difficult time visualizing the action of the story. Below is an example of how a writer might establish setting in a way which immerses the reader: by showing rather than telling.

Telling |

Showing |

|---|---|

| I went to the lake. It was cool. | My breath escaped in ragged bursts, my quadriceps burning as I crested the summit. The lake stretched before me, aquamarine, glistening in the hot August afternoon sun. Ponderosa pines lined its shores, dropping their spicy-scented needles into the clear water. Despite the heat, the Montana mountain air tasted crisp. |

Which of the above lakes would you want to visit? Which one paints a more immersive picture, making you feel like you are there? When writing a story, our initial instinct is usually to make a list of chronological moments: first I did this, then I did this, then I did that, it was neat-o. That might be factual, but it does not engage the reader or invite them into your world. It bores the reader. Ever been stuck listening to someone tell a story that seems like it will never end? It probably was someone telling you a story rather than using the five senses to immerse you. In the example above, the writer uses visual (sight), auditory (sound), olfactory (smell), tactile (touch), or gustatory (taste) imagery to help the reader picture the setting in their mind. By the final draft, the entire story should be compelling and richly detailed. While it's fine to have an outline or first draft that recounts the events of the story, the final draft should include dialogue, immersive description, plot twists, and metaphors to capture your reader's attention as you write.

"Eibsee Lake" by barnyz, 2 August 2011, published on Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Descriptive Imagery

You have probably encountered descriptive imagery before. Basically, it is the way the writer paints the scene, or image, in the mind of the reader. It usually involves descriptions of one or more of the five senses: sight, sound, smell, touch, or taste. For example, how would you describe a lemon to a person who has never seen one before?

"Lemon" by André Karwath (2005) is licensed CC BY-SA 2.5

Imagine you are describing a lemon to someone who has never seen one before. How would you describe it using all five senses?

- Sight

- Sound

- Smell

- Touch

- Taste

One might describe a lemon as yellow, sour-smelling and tasting, and with a smooth, bumpy skin. They might describe the sound of the lemon as a thump on the table if it is dropped, or squelching if it is squished underfoot. By painting a picture in the reader's mind, it immerses them in the story so that they feel they are actually there.

Figurative Language

As a counterpart to descriptive imagery, figurative language is using language in a surprising way to describe a literary moment. Figurative language can take the form of metaphor, such as saying "the lemon tree was heavy with innumerable miniature suns." Since the lemons are not actually suns, this is figurative. Figurative language can also take the form of simile: "aunt Becky's attitude was as sour as a lemon." By comparing an abstract concept (attitude) to an object (lemon), it imparts a feeling/meaning in a more interesting way.

Plot

Plot is one of the basic elements of every story: put simply, plot refers to the actual events that take place within the bounds of your narrative. Using our rhetorical situation vocabulary, we can identify “plot” as the primary subject of a descriptive personal narrative. Three related elements to consider are scope, sequence, and pacing.

Scope

The term scope refers to the boundaries of plot. Where and when does the story begin and end? What is its focus? What background information and details does the story require? I often think about narrative scope as the edges of a photograph: a photo, whether of a vast landscape or a microscopic organism, has boundaries. Those boundaries inform the viewer’s perception.

The way we determine scope varies based on rhetorical situation, but I can say generally that many developing writers struggle with a scope that is too broad: writers often find it challenging to zero in on the events that drive a story and prune out extraneous information.

Consider, as an example, how you might respond if your friend asked what you did last weekend. If you began with, “I woke up on Saturday morning, rolled over, checked my phone, fell back asleep, woke up, pulled my feet out from under the covers, put my feet on the floor, stood up, stretched…” then your friend might have stopped listening by the time you get to the really good stuff. Your scope is too broad, so you’re including details that distract or bore your reader. Instead, focus on the most exciting or meaningful moment(s) of your day: "I woke up face-down to the crunch of shattered glass underneath me. When I wobbled to my feet I realized I was in a large, marble room with large windows overlooking the flashing neon lights of the Las Vegas strip. I had no idea how I got there!" Readers can expect this story will focus on how the storyteller arrived in Las Vegas, and it is much more interesting than including every single detail of the day.

Sequence

The sequence of your plot—the order of the events—will determine your reader’s experience. There are an infinite number of ways you might structure your story, and the shape of your story is worth deep consideration. Although the traditional forms for a narrative sequence are not your only options, let’s take a look at a few tried-and-true shapes your plot might take.

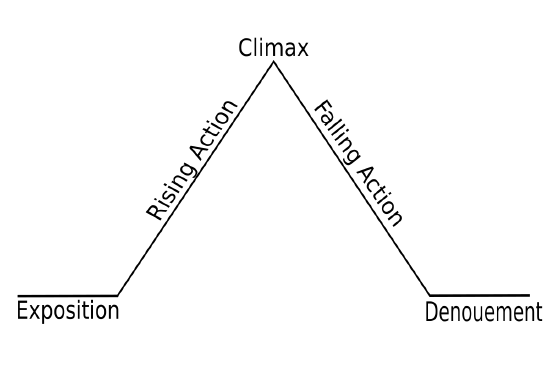

Freytag's Pyramid is in the public domain

Freytag's Pyramid: Chronological

A. Exposition: Here, you’re setting the scene, introducing characters, and preparing the reader for the journey.

B. Rising action: In this part, things start to happen. You (or your characters) encounter conflict, set out on a journey, meet people, etc.

C. Climax: This is the peak of the action, the main showdown, the central event toward which your story has been building.

D. Falling action: Now things start to wind down. You (or your characters) come away from the climactic experience changed—at the very least, you are wiser for having had that experience.

E. Resolution: Also known as dénouement, this is where all the loose ends get tied up. The central conflict has been resolved, and everything is back to normal, but perhaps a bit different.

In Medias Res

While Freytag's Pyramid tends to follow a linear or chronological structure, a story that begins in medias res begins in the middle of the action. In fact, the Latin translation for this term most literally means "in the middle of things." This is a more exciting way to start a story in that it grabs the readers' attention quickly.

There I was floating in the middle of the ocean, the sharks with laser beams attached to their heads circling hungrily, the red lights bouncing off of the floating disco ball upon which I clung to for dear life, when I thought back to the events which led to this horrifying situation...

The best In Medias Res beginnings make the reader go "WHAT THE HECK IS GOING ON HERE?" and want to continue reading. They will usually follow the following inversion of Freytag's Pyramid:

C. Climax: This is the peak of the action, the main showdown, the central event of the story where the conflict comes to a head.

A. Exposition: Here, you’re setting the scene, introducing characters, and preparing the reader for the journey.

B. Rising action: In this part, things start to happen. You (or your characters) encounter conflict, set out on a journey, meet people, etc.

C. Climax: the story briefly returns to the moment where it started, though usually not in a way which is redundant (not the exact same writing or details)

D. Falling action: Now things start to wind down. You (or your characters) come away from the climactic experience changed—at the very least, you are wiser for having had that experience.

E. Resolution: Also known as dénouement, this is where all the loose ends get tied up. The central conflict has been resolved, and everything is back to normal, but perhaps a bit different.

Nonlinear Narrative

A nonlinear narrative may be told in a series of flashbacks or vignettes. It might jump back and forth in time. Stories about trauma are often told in this fashion. If using this plot form, be sure to make clear to readers how/why the jumps in time are occurring. A writer might clarify jumps in time by adding time-stamps or dates or by using symbolic images to connect different vignettes.

Pacing

While scope determines the boundaries of plot, and sequencing determines where the plot goes, pacing determines how quickly readers move through the story. In short, it is the amount of time you dedicate to describing each event in the story.

I include pacing with sequence because a change to one often influences the other. Put simply, pacing refers to the speed and fluidity with which a reader moves through your story. You can play with pacing by moving more quickly through events, or even by experimenting with sentence and paragraph length. Consider how the “flow” of the following examples differ:

|

The train screeched to a halt. A flock of pigeons took flight as the conductor announced, “We’ll be stuck here for a few minutes.” |

Lost in my thoughts, I shuddered as the train ground to a full stop in the middle of an intersection. I was surprised, jarred by the unannounced and abrupt jerking of the car. I sought clues for our stop outside the window. All I saw were pigeons as startled and clueless as I. |

Characters

A major requirement of any story is the use of characters. Characters bring life to the story. Keep in mind that while human characters are most frequently featured in stories, sometimes there are non-human characters in a story such as animals or even the environment itself. Consider, for example, the ways in which the desert itself might be considered a character in "Bajadas" by Francisco Cantú.

Characterization

Whether a story is fiction or nonfiction, writers should spend some time thinking about characterization: the development of characters through actions, descriptions, and dialogue. Your audience will be more engaged with and sympathetic toward your narrative if they can vividly imagine the characters as real people.

Like setting description, characterization relies on specificity. Consider the following contrast in character descriptions:

|

My mom is great. She is an average-sized brunette with brown eyes. She is very loving and supportive, and I know I can rely on her. She taught me everything I know. |

In addition to some of my father’s idiosyncrasies, however, he is also one of the most kind-hearted and loving people in my life. One of his signature actions is the ‘cry-smile,’ in which he simultaneously cries and smiles any time he experiences a strong positive emotion (which is almost daily). |

How does the “cry-smile” detail enhance the characterization of the speaker’s parent?

To break it down to process, characterization can be accomplished in two ways:

- Directly, through specific description of the character—What kind of clothes do they wear? What do they look, smell, sound like?—or,

- Indirectly, through the behaviors, speech, and thoughts of the character—What kind of language, dialect, or register do they use? What is the tone, inflection, and timbre of their voice? How does their manner of speaking reflect their attitude toward the listener? How do their actions reflect their traits? What’s on their mind that they won’t share with the world?

Thinking through these questions will help you get a better understanding of each character (often including yourself!). You do not need to include all the details, but they should inform your description, dialogue, and narration.

|

Round characters |

are very detailed, requiring attentive description of their traits and behaviors. |

Your most important characters should be round: the added detail will help your reader better visualize, understand, and care about them. |

|---|---|---|

|

Flat characters |

are minimally detailed, only briefly sketched or named. |

Less important characters should take up less space and will therefore have less detailed characterization. |

|

Static characters |

remain the same throughout the narrative. |

Even though all of us are always changing, some people will behave and appear the same throughout the course of your story. Static characters can serve as a reference point for dynamic characters to show the latter’s growth. |

|

Dynamic characters |

noticeably change within the narrative, typically as a result of the events. |

Most likely, you will be a dynamic character in your personal narrative because such stories are centered around an impactful experience, relationship, or place. Dynamic characters learn and grow over time, either gradually or with an epiphany. |

Point of View

The position from which your story is told will help shape your reader’s experience, the language your narrator and characters use, and even the plot itself. You might recognize this from Dear White People Volume 1 or Arrested Development Season 4, both Netflix TV series. Typically, each episode in these seasons explores similar plot events, but from a different character’s perspective. Because of their unique vantage points, characters can tell different stories about the same realities.

This is, of course, true for our lives more generally. In addition to our differences in knowledge and experiences, we also interpret and understand events differently. In our writing, narrative position is informed by point-of-view and the emotional valences I refer to here as tone and mood.

point-of-view (POV): the perspective from which a story is told.

- This is a grammatical phenomenon—i.e., it decides pronoun use—but, more importantly, it impacts tone, mood, scope, voice, and plot.

Although point-of-view will influence tone and mood, we can also consider what feelings we want to convey and inspire independently as part of our narrative position.

tone: the emotional register of the story’s language.

- What emotional state does the narrator of the story (not the author, but the speaker) seem to be in? What emotions are you trying to imbue in your writing?

mood: the emotional register a reader experiences.

- What emotions do you want your reader to experience? Are they the same feelings you experienced at the time?

A Non-Comprehensive Breakdown of POV

|

1st person |

Narrator uses 1st person pronouns (I/me/mine or us/we/ours) |

Can include internal monologue (motives, thoughts, feelings) of the narrator. Limited certainty of motives, thoughts, or feelings of other characters. |

I tripped on the last stair, preoccupied by what my sister had said, and felt my stomach drop. |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2nd person |

Narrator uses 2nd person pronouns (you/you/your) |

Speaks to the reader, as if the reader is the protagonist OR uses apostrophe to speak to an absent or unidentified person |

Your breath catches as you feel the phantom step. O, staircase, how you keep me awake at night. |

|

3rd person limited |

Narrator uses 3rd person pronouns (he/him/his, she/her/hers, they/they/theirs) |

Sometimes called “close” third person. Observes and narrates but sticks near one or two characters, in contrast with 3rd person omniscient. |

He was visibly frustrated by his sister’s nonchalance and wasn’t watching his step. |

|

3rd person omniscient |

Narrator uses 3rd person pronouns (he/him/his, she/her/hers, they/they/theirs) |

Observes and narrates from an all-knowing perspective. Can include internal monologue (motives, thoughts, feelings) of all characters. |

Beneath the surface, his sister felt regretful. Why did I tell him that? she wondered. |

|

stream-of-consciousness |

Narrator uses inconsistent pronouns, or no pronouns at all |

Approximates the digressive, wandering, and ungrammatical thought processes of the narrator. |

But now, a thousand empty⎯where?⎯and she, with head shake, will be fine⎯AHH! |

Typically, you will tell your story from the first-person point-of-view, but personal narratives can also be told from a different perspective; I recommend “Comatose Dreams” to illustrate this at work. As you’re developing and revising your writing, try to inhabit different authorial positions: What would change if you used the third person POV instead of first person? What different meanings would your reader find if you told this story with a different tone—bitter instead of nostalgic, proud rather than embarrassed, sarcastic rather than genuine?

Furthermore, there are many rhetorical situations that call for different POVs. (For instance, you may have noticed that this book uses the second-person very frequently.) So, as you evaluate which POV will be most effective for your current rhetorical situation, bear in mind that the same choice might inform your future writing.

Dialogue

dialogue: communication between two or more characters. For example...

"Hate to break it to you, but your story is boring."

"What? Why do you say that?" he stuttered as his face reddened.

"Because you did not include any dialogue," she laughed.

Think of the different conversations you’ve had today, with family, friends, or even classmates. Within each of those conversations, there were likely pre-established relationships that determined how you talked to each other: each is its own rhetorical situation. A dialogue with your friends, for example, may be far different from one with your family. These relationships can influence tone of voice, word choice (such as using slang, jargon, or lingo), what details we share, and even what language we speak.

Good dialogue often demonstrates the traits of a character or the relationship of characters. From reading or listening to how people talk to one another, we often infer the relationships they have. We can tell if they’re having an argument or conflict, if one is experiencing some internal conflict or trauma, if they’re friendly acquaintances or cold strangers, even how their emotional or professional attributes align or create opposition.

Often, dialogue does more than just one thing, which makes it a challenging tool to master. When dialogue isn’t doing more than one thing, it can feel flat or expositional, like a bad movie or TV show where everyone is saying their feelings or explaining what just happened. For example, there is a difference between “No thanks, I’m not hungry” and “I’ve told you, I’m not hungry.” The latter shows frustration, and hints at a previous conversation. Exposition can have a place in dialogue, but we should use it deliberately, with an awareness of how natural or unnatural it may sound. We should be aware how dialogue impacts the pacing of the narrative. Dialogue can be musical and create tempo, with either quick back and forth, or long drawn out pauses between two characters. Rhythm of a dialogue can also tell us about the characters’ relationship and emotions.

Contributors and Attributions

- Adapted from "Chapter 2: Telling a Story" from EmpoWord by Shane Abrams, Chapter 2, licensed CC BY NC 4.0 by Portland State University