4.12: Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804–1846)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Nathaniel Hawthorne was born in 1804 to Nathaniel Hawthorne, Senior and Elizabeth Manning Hawthorne. His father was a sea-captain who died in 1808 of yellow fever. Hawthorne’s mother then moved with her children to her family’s home in Salem. Her family had a long history in Salem, and among Harthorne’s ancestor was a judge in the Salem witch trials of 1692.

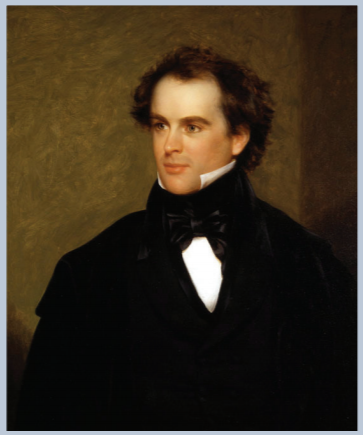

Image 4.12.1: Nathaniel Hawthorne

During his childhood in Salem, Hawthorne acquired a love of reading, particularly of long prose works and early novels-as-genre by such writers as John Bunyan (1628–1688), Tobias Smollett (1721–1771), and Sir Walter Scott. Intent on becoming a writer, Hawthorne entered Bowdoin College in Maine, where the Manning family had property. Several of his classmates, including Horatio Bridge (1806–1893) and later president Franklin Pierce (1804–1869), would become life-long friends and supporters of both his livelihood and his writing.

After graduating, Hawthorne immersed himself in antiquarian pursuits, studying Puritan and colonial history. Many of his stories would consider Puritanism’s effect on the American consciousness, particularly in regards to the place of evil—and its inevitable impact on human life—in the American individual and their context in society. The stories would also give an American slant to universal concerns, concerns such as potential conflicts of individual freedom and destiny and humankind’s place (if any) in the wilderness/nature, and, perhaps, in eternity. Sensitive to how Puritans would confuse the concrete and particular with the abstract and spiritual, Hawthorne often used allegory and symbolism in order to give shading to Puritans’ apparently clear-cut, black and white certainties. He would link Puritan certainties about human nature with more natural human uncertainties and ambiguities.

His first published novel derived not from his antiquarian studies but from his experiences at Bowdoin. Published at his own expense, Fanshawe (1828) proved such a failure that Hawthorne halted its distribution. Despite this failure, he successfully placed contemporary and historical prose pieces in Christmas annuals, many in The Token, edited by Samuel Griswold Goodrich (1793—1860). His friend Bridge encouraged Hawthorne to publish a collection of this work and, unknown to Hawthorne, offered to defray its publisher, the American Stationers’ Company, for any publishing losses. Twice-Told Tales came out in 1837 to much critical, though little financial, success. Hawthorne followed it with historical children’s books, including Liberty Tree (1841), and an expanded edition of TwiceTold Tales (1842).

To earn a steady income, Hawthorne worked at the Boston Custom House (1839–1840) and invested money in and lived for a brief stint at the utopian Brook Farm in West Roxbury, an experiment that ultimately failed. In 1842, he married Sophia Peabody. They moved into a house owned by Emerson’s family, the Old Manse, in Concord. There, Hawthorne became part of the important literary milieu that included Thoreau, Fuller, and Emerson.

His story collection Mosses from an Old Manse came out in 1846. It also offered little financial success. Hawthorne returned to Salem where he worked in the Salem Custom House (1846—1849), losing this position when the Democrats lost the next election. He used his experiences at the Custom House in the long introduction to The Scarlet Letter (1850), the novel that won Hawthorne longlasting fame. This work dramatizes sin, punishment, and redemption—and their effects not only on its heroine, Hester Prynne, but also on her partner in adultery, her cuckolded husband, and the surrounding Puritan community and government that confuses the internal and external self. Hester Prynne both embodies and transcends the scarlet letter “A” she is forced to wear on her breast as punishment for her adultery. Her lover, the Puritan minister Arthur Dimmesdale, underscores the hidden inner self by continuing his public ministerial activities even while bearing a comparable scarlet letter seared into his chest.

Hawthorne further explored the consequences of inherited sin and the mysteries (and contradictions) of the human spirit in The House of Seven Gables (1851) and The Blithedale Romance (1852). Just preceding these publications, Hawthorne became friends with Herman Melville and perhaps inspired him to turn from writing adventure tales to literary works treating of providence, human will, and all the unknowns in between.

Hawthorne’s The Life of Franklin Pierce (1852) led recently-elected President Pierce to appoint Hawthorne as the American consul in Liverpool (1853—1847). His consequent travels in England and on the Continent resulted in The Marble Faun (1860) and a collection of essays, Our Old Home (1863). Set in Rome, The Marble Faun remained popular throughout the nineteenth-century, even being used as a guidebook by American travelers abroad.

In 1860, Hawthorne and his family returned to their home, The Wayside, in Concord. In “Chiefly About War Matters” (1862), he deplored the violence of the Civil War and its terrible transformative effects on America, both the North and South. Even then, he was still using his writing to explore the complexities of the human heart.