4.10: Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882)

- Page ID

- 57472

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Ralph Waldo Emerson, in his essays, poems, and lectures, clarified and distilled such quintessential American values as individualism, self-reliance, self-education, non-conformity, and anti-institutionalism. He asserted the individual’s intuitive grasp of immensity, divinity—or soul—in observable nature. He brought to human scale and his own understanding the metaphysical Absolute united in the physical and in all life.

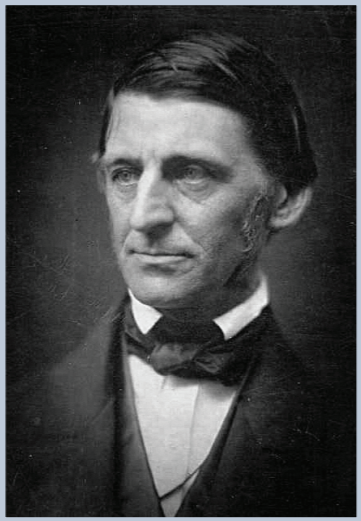

Image \(\PageIndex{1}\): Ralph Waldo Emerson

This latter vision would inspire a group of his friends, who met at his home in Concord, to develop a Transcendentalist philosophy influenced by German and British Romanticism; higher criticism of the Bible, that is of the origins of the text; the philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724 – 1804); and German Idealism, a doctrine considering the differences in appearances —as objects of human cognition—and things in themselves. Rejecting John Locke’s view of the mind as a tabula rasa and passive receptor, these Transcendentalists saw instead an interchange between the individual mind and nature (nature as animated and inspirited), an interchange that received and created a sense of the spirit, or the Over-soul. They rejected institutions and dogma in favor of their own individuality and independence as better able to maintain the inherent goodness in themselves and perception of goodness in the world around them.

Emerson was early introduced to a spiritual life, particularly through his father William Emerson (1769–1811), a Unitarian minister in Boston. He died in 1811, when Emerson was eight. His mother, Ruth Haskins Emerson (1768–1853), kept boardinghouses to support her six children and see to their education. Emerson was educated at the Boston Latin School in Concord and at Harvard College. From 1821 to 1825, he taught at his brother William’s Boston School for Young Ladies then entered Harvard Divinity School.

In 1829, Emerson was ordained as Unitarian minister of Boston’s Second Church; he also married Ellen Louisa Tucker, who died two years later from tuberculosis. Her death caused Emerson great grief and may have propelled him in 1832 to resign from his church, which he came to see as institutionalizing Christianity, thereby causing church-goers to experience Christianity at a remove, so to speak. Emerson later affirmed his views and broke permanently with the Unitarian church in his “Divinity School Address” (1838), protesting the church’s having dogmatized and formalized faith, morality, and God. Emerson thought the church turned God from a living spirit and reality into a fixed convention, evoking only a historical Christianity—making God seem a thing of the past and dead.

From 1832 to 1833, Emerson traveled in Europe where he met such influential writers and thinkers as William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Thomas Carlyle (1795—1881). He and Carlyle remained life-long friends. When he returned to America, Emerson settled a legal dispute over his wife’s legacy, through which he ultimately acquired an annual income of 1,000 pounds. He began lecturing around New England, married Lydia Jackson, and settled in Concord, at a house near ancestral property. In 1836, he anonymously published—at his own expense—his first book, Nature. It expressed his spiritual and transcendentalist views and drew to Concord such like-minded friends as Bronson Alcott (1799— 1888), Margaret Fuller, and Henry David Thoreau. They started The Dial (1840— 1844), a Transcendentalist journal edited mainly by Emerson, Fuller, and Thoreau.

Staying true to his individualist views, Emerson often visited but did not join the utopian experiment of Brook Farm (1841–1847), a co-operative community whose residents included Nathaniel Hawthorne and the Unitarian minister George Ripley (1802—1880). Emerson did continue to lecture across America and abroad in England and Scotland. He publicly condemned slavery in his “Emancipation of the Negroes in the British West Indies” (1841) and later attacked the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. He also supported women’s suffrage and right to own property. Emerson published a number of prose collections drawn from his lectures, including his first Essays (1841), Essays: Second Series (1844), Representative Men (1850), and The Conduct of Life (1860).

In Poems (1847) and May-Day and Other Poems (1867), he also published poetry notable for its metrical irregularity; poetry that, though disparaged by many contemporary critics, inspired the long line of Walt Whitman. Indeed, Emerson became one of Whitman’s earliest champions. Through his life and work, Emerson promoted literary nationalism and a distinctly American culture.