2.3: Sentence Structure Boundaries and Associated Errors

- Page ID

- 50989

Sentence Structure

Chapter 1 covered the basics of sentence structure in creating a good sentences. It also covered the variety of sentence patterns to make good sentences. As mentioned before, good writers use a variety of sentence structures to make their work more interesting. However, students may have sentence structure issues and you need to understand how these sentences are put together and how to fix the errors possibly made in writing. This section will cover a variety of sentence structure boundaries and show you how to fix those errors you may have such as fragments, comma splices and run-ons.

Fragments

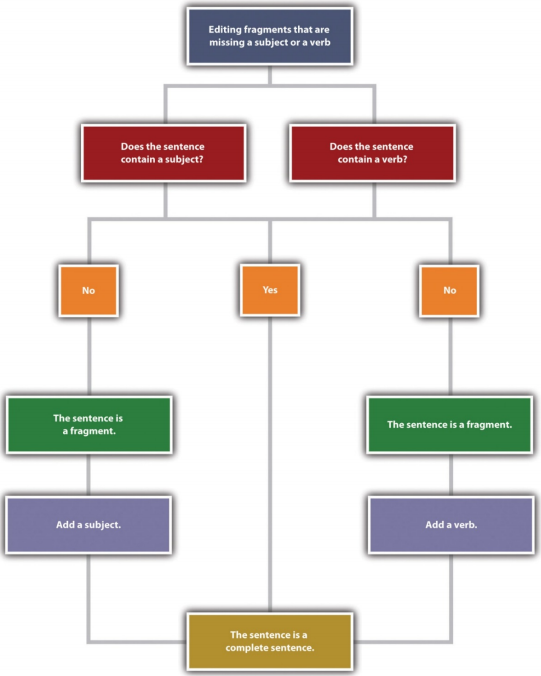

As mentioned in Chapter 1, a sentence that is missing a subject or a verb is called a fragment. You can easily fix a fragment by adding the missing subject or verb.

See whether you can identify what is missing in the following fragments:

Fragment: Told her about the broken vase.

Complete sentence: I told her about the broken vase.

Fragment: The store down on Main Street.

Complete sentence: The store down on Main Street sells music.

The following Figure on the next page gives you a good path to fix errors:

Common Sentence Errors Which Cause Fragments

Fragments often occur because of some common error, such as starting a sentence with a preposition, a dependent word, an infinitive, or a gerund. If you use the six basic sentence patterns discussed in Chapter 1 when you write, you should be able to avoid these errors and thus avoid writing fragments.

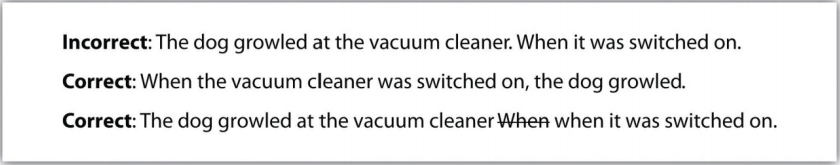

When you see a preposition, check to see that it is part of a sentence containing a subject and a verb. If it is not connected to a complete sentence, it is a fragment, and you will need to fix this type of fragment by combining it with another sentence. You can add the prepositional phrase to the end of the sentence. If you add it to the beginning of the other sentence, insert a comma after the prepositional phrase.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\):

The figure on the following page shows you the method to edit fragments that begin with a preposition:

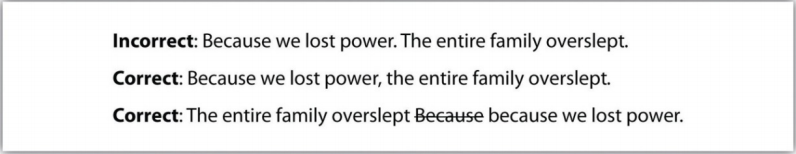

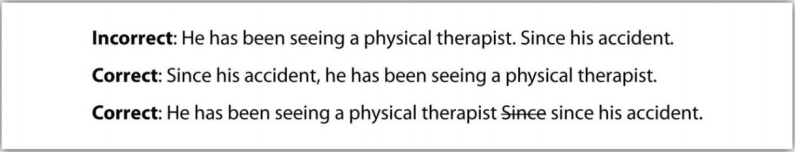

Clauses that start with a dependent word — such as since, if, because, when, although, even though, after, without, or unless — are similar to prepositional phrases. Like prepositional phrases, these clauses can be fragments if they are not connected to an independent clause containing a subject and a verb. To fix the problem, you can add such a fragment to the beginning or end of a sentence. If the fragment is added at the beginning of a sentence, add a comma.

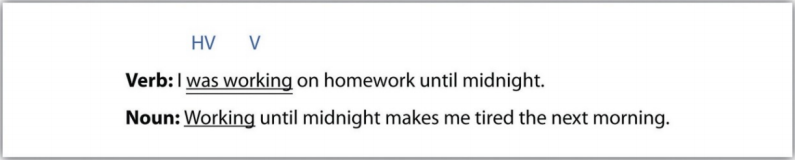

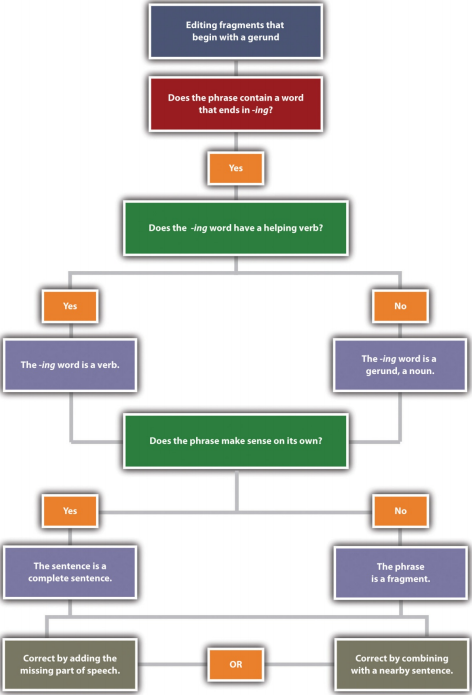

When you encounter a word ending in -ing in a sentence, identify whether or not this word is used as a verb in the sentence. You may also look for a helping verb. If the word is not used as a verb or if no helping verb is used with the -ing verb form, the verb is being used as a noun. An -ing verb form used as a noun is called a gerund.

Once you know whether the -ing word is acting as a noun or a verb, look at the rest of the sentence. Does the entire sentence make sense on its own? If not, what you are looking at is a fragment. You will need to either add the parts of speech that are missing or combine the fragment with a nearby sentence.

Incorrect: Taking deep breaths. Saul prepared for his presentation.

Correct: Taking deep breaths, Saul prepared for his presentation.

Correct: Saul prepared for his presentation. He was taking deep breaths.

Incorrect: Congratulating the entire team. Sarah raised her glass to toast their success.

Correct: She was congratulating the entire team. Sarah raised her glass to toast their success.

Correct: Congratulating the entire team, Sarah raised her glass to toast their success.

The figure on the following page shows you the method to edit fragments that begin with a gerund:

Another error in sentence construction is a fragment that begins with an infinitive. An infinitive is a verb paired with the word to; for example, to run, to write, or to reach are all infinitives. Although infinitives are verbs, they can be used as nouns, adjectives, or adverbs. You can correct a fragment that begins with an infinitive by either combining it with another sentence or adding the parts of speech that are missing.

Incorrect: We needed to make three hundred more paper cranes. To reach the one thousand mark.

Correct: We needed to make three hundred more paper cranes to reach the one thousand mark.

Correct: We needed to make three hundred more paper cranes. We wanted to reach the one thousand mark.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\):

Copy the following sentences onto your own sheet of paper and circle the fragments. Then combine the fragment with the independent clause to create a complete sentence.

- Working without taking a break. We try to get as much work done as we can in an hour.

- I needed to bring work home. In order to meet the deadline.

- Unless the ground thaws before spring break. We won’t be planting any tulips this year.

- Turning the lights off after he was done in the kitchen. Mohammed tries to conserve energy whenever possible.

- You’ll find what you need if you look. On the shelf next to the potted plant.

- To find the perfect apartment. Thuy scoured the classifieds each day

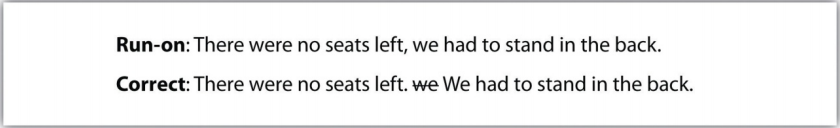

Run-on Sentences

Just as short, incomplete sentences can be problematic, lengthy sentences can be problematic too. Sentences with two or more independent clauses that have been incorrectly combined are known as run-on sentences. A run-on sentence may consist of either a fused sentence or a comma splice or both.

When two complete sentences are combined into one without any punctuation, the result is a fused sentence.

Fused sentence: A family of foxes lived under our shed young foxes played all over the yard.

When two complete sentences are joined by a comma, the result is a comma splice.

Comma splice: We looked outside, the kids were hopping on the trampoline.

Writers sometimes create run-ons that are an entire paragraph. An example of writing with both a fused sentence and a comma splice is the following:

Fused sentence and comma splice: A good communicator always possesses these traits like being a good and non-interruptive listener this is the #1 traits that lets people know if you are a good communicator, Confidence is one of them, Good posture, Respect, Clarity, Eye contact, body language is another important of them too because we have verbal and non-verbal communication we have people who cannot talk but use sign language to communicate.

Correcting a Run-on Sentence

Punctuation

One way to correct run-on sentences is to correct the punctuation. For example, adding a period will correct the run-on by creating two separate sentences.

Using a semicolon between the two complete sentences will also correct the error. A semicolon allows you to keep the two closely related ideas together in one sentence. When you punctuate with a semicolon, make sure that both parts of the sentence are independent clauses. For more information on semicolons, see Chapter 8.

Run-on: The accident closed both lanes of traffic we waited an hour for the wreckage to be cleared.

Complete sentence: The accident closed both lanes of traffic; we waited an hour for the wreckage to be cleared.

When you use a semicolon to separate two independent clauses, you may wish to add a transition word to show the connection between the two thoughts. After the semicolon, add the transition word and follow it with a comma. For more information on transition words, see Chapter 8.

Run-on: The project was put on hold we didn’t have time to slow down, so we kept working.

Complete sentence: The project was put on hold; however, we didn’t have time to slow down, so we kept working.

Coordinating Conjunctions (FANBOYS)

You can also fix run-on sentences by adding a comma and a coordinating conjunction. A coordinating conjunction acts as a link between two independent clauses. The acronym FANBOYS will help you remember this group of coordinating conjunctions. These are the seven coordinating conjunctions that you can use: for, and, nor, but, or, yet, and so. Use these words appropriately when you want to link the two independent clauses.

Run-on: The new printer was installed, no one knew how to use it.

Complete sentence: The new printer was installed, but no one knew how to use it.

Dependent Words (Conjunctive Adverbs)

Adding dependent words is another way to link independent clauses. Like the coordinating conjunctions, dependent words show a relationship between two independent clauses.

Run-on: We took the elevator, the others still got there before us.

Complete sentence: Although we took the elevator, the others got there before us.

Run-on: Cobwebs covered the furniture, the room hadn’t been used in years.

Complete sentence: Cobwebs covered the furniture because the room hadn’t been used in years.

Discussion:

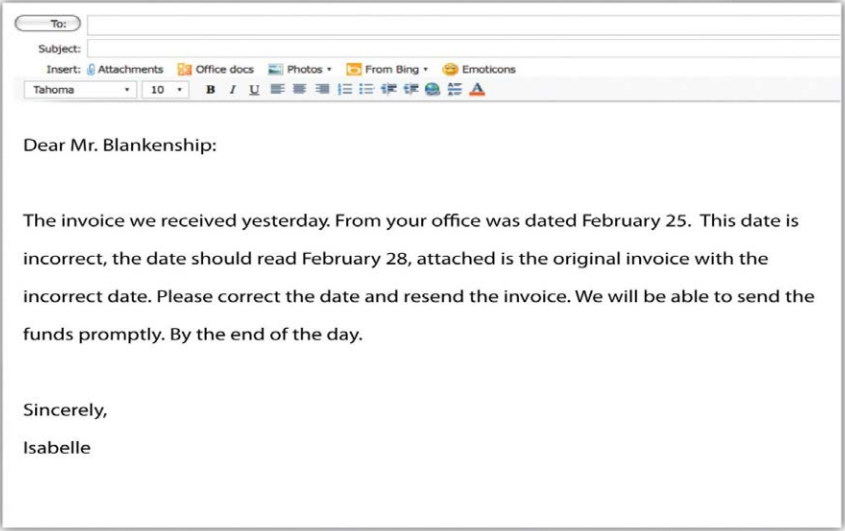

Isabelle’s e-mail opens with two fragments and two run-on sentences containing comma splices. The e-mail ends with another fragment. What effect would this e-mail have on Mr. Blankenship or other readers? Mr. Blankenship or other readers may not think highly of Isabelle’s communication skills or — worse — may not understand the message at all! Communications written in precise, complete sentences are not only more professional but also easier to understand. Before you hit the “send” button, read your e-mail carefully to make sure that the sentences are complete, are not run together, and are correctly punctuated.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\):

A reader can get lost or lose interest in material that is too dense and rambling. Use what you have learned about run-on sentences to correct the following passages:

- The report is due on Wednesday but we’re flying back from Miami that morning. I told the project manager that we would be able to get the report to her later that day she suggested that we come back a day early to get the report done and I told her we had meetings until our flight took off. We e-mailed our contact who said that they would check with his boss, she said that the project could afford a delay as long as they wouldn’t have to make any edits or changes to the file our new deadline is next Friday.

- Ana tried getting a reservation at the restaurant, but when she called they said that there was a waiting list so she put our names down on the list when the day of our reservation arrived we only had to wait thirty minutes because a table opened up unexpectedly which was good because we were able to catch a movie after dinner in the time we’d expected to wait to be seated.

- Without a doubt, my favorite artist is Leonardo da Vinci, not because of his paintings but because of his fascinating designs, models, and sketches, including plans for scuba gear, a flying machine, and a life-size mechanical lion that actually walked and moved its head. His paintings are beautiful too, especially when you see the computer enhanced versions researchers use a variety of methods to discover and enhance the paintings’ original colors, the result of which are stunningly vibrant and yet delicate displays of the man’s genius.

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\):

Edit this paragraph on your own paper to fix the run-on issues:

Communication is a big topic that if I keep going I could write up to two pages, in conclusion communication is the way of life it can detect ones’ feelings and emotions and that’s where body language comes in because you can tell if someone is paying attention to you speak by the way they are sitting, looking or even the way they answer or reply to you, we all can be good communicators if we listen more before we speak that’s why we have one mouth and two ears talk less and listen more.

Key Takeaways

- A sentence is complete when it contains both a subject and verb. A complete sentence makes sense on its own. Otherwise, it is a fragment!

- Every sentence must have a subject, which usually appears at the beginning of the sentence. A subject may be a noun (a person, place, or thing) or a pronoun.

- A compound subject contains more than one noun.

- A prepositional phrase describes, or modifies, another word in the sentence but cannot be the subject of a sentence.

- A verb is often an action word that indicates what the subject is doing. Verbs may be action verbs, linking verbs, or helping verbs.

- Variety in sentence structure and length improves writing by making it more interesting and more complex.

- Focusing on the six basic sentence patterns will enhance your writing.

- Fragments and run-on sentences are two common errors in sentence construction.

- Fragments can be corrected by adding a missing subject or verb. Fragments that begin with a preposition or a dependent word can be corrected by combining the fragment with another sentence.

- Run-on sentences can be corrected by adding appropriate punctuation or adding a coordinating conjunction.