1.1: Introduction to Academic Writing

- Page ID

- 53670

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Becoming a Successful Writer

In her book On Writing, Eudora Welty maintains: “To write honestly and with all our powers is the least we can do, and the most.” But writing well is difficult. People who write for a living sometimes struggle to get their thoughts on the page; even people who generally enjoy writing have days when they would rather do anything else. For people who do not like writing or do not think of themselves as good writers, writing assignments can be stressful or even intimidating. And, of course, you cannot get through college without having to write—sometimes a lot, and often at a higher level than you are used to. No magic formula will make writing quick and easy. However, you can use strategies and resources to manage writing assignments more easily. College will challenge you as a writer, but it is also a unique opportunity to grow.

Writing to Think and Communicate

One purpose of writing is to help you clarify and articulate your thoughts. Writing a list of points, both pro and con, on an issue of concern allows you to see which of your arguments are the strongest or reveals areas that need additional support. Putting ideas on paper helps you review and evaluate them, reconsider their validity, and perhaps generate new concepts. Writing your thoughts down may even help you grasp them for the first time.

Another important—and practical—function of writing is to communicate ideas. For your college classes you are required to write essays, research papers, and essay responses on tests. If you apply to other colleges or universities, you will have to compose letters of application, respond to specific questions, or write an autobiographical sketch. When you enter your chosen career you may have to send emails and write reports, proposals, grants, or other work-related documents. You must correspond with clients, business associates, and co-workers. And on a personal level, you want to contact friends and relatives. You may even find yourself responding to a community or national issue by writing a letter to the editor of your local newspaper.

Writing is an essential skill you must have in order to function in the twenty-first century, but like any skill, it is something that can be acquired and refined. Some people just naturally express themselves better than others, but everyone can learn the basic craft of writing.

Overcoming Writer’s Block

At some point, every writer experiences writer’s block: staring at a blank page or computer screen without being able to put down even a single line. Your mind is blank, and panic sets in because writer’s block usually happens when you are working against a deadline such as in a timed writing assignment or for a paper that is due the next day. Even though there is nothing you can do to prevent writer’s block from happening, there are several techniques you can use to help you overcome its negative effects:

- Don’t Procrastinate: Give yourself as much time as possible to complete your assignment. Budget your time so you can write the assignment in sections and still have time to edit and revise. If you are in a timed writing situation, jot down ideas in a scratch outline and work from that.

- Try Freewriting without Guilt: Just start putting ideas down on paper. You don’t need to worry about whether or not you are making spelling and grammatical errors; you shouldn’t fret over organization. Keep in mind that you can always delete what you have written once your ideas begin to flow.

- Follow Your Inspiration: Begin by writing the section of the paper you feel best able to write. If you cannot start at the beginning, write the conclusion first, or begin writing the body of the paper. If you have an outline, you will already have the ideas and organization you need to write the body paragraphs.

- Break the Writing Project into Parts: Think of the paper as a series of short sections. Sometimes you can be overwhelmed by the prospect of writing a ten-page research paper, but if you break it up into manageable pieces, the assignment does not seem so daunting.

- Review the Assignment: Reread the instructions for the assignment to make sure you understand what you are expected to write. Look for keywords that you can research to give you insight into your topic. Often discussing the assignment with your professor can give you the clarity you need to begin writing.

- Verbalize Your Ideas: Discuss your ideas with a classmate, friend or family member. You can gain new insights and confidence by hearing what others have to say about your topic and sharing your misgivings with them.

- Visualize a Friendly Audience: Imagine you are writing the paper to a friend or someone you know well. Often the fear of rejection paralyzes your ability to start writing, so removing that obstacle should enable you to write without inhibition.

- Take a Break: Try working on another writing project or switch to a completely different activity. Often if you get bogged down on one subject, thinking about something else for a while might clear your brain so you can come back to the original project with a new perspective. And getting up from the computer usually unclogs any mental blocks: take a walk, wash the dishes, or play with the dog.

- Change Locations: Try moving to another area more conducive to your writing style. Some people write best in a noisy environment while others require a place with minimal distractions. Find what works best for you.

Remember that writer’s block is only temporary—relax and start writing.

Selecting an Appropriate Voice

Whether you are writing an argumentative essay expressing your conviction that whale hunting should be abolished or a literary analysis of Kate Chopin’s novel The Awakening, your paper should express a distinct point of view. Your purpose should be to convince your audience that you have something worthwhile to say. Gaining their approval depends to a large degree on their perception of the writer: you need to present yourself as educated, rational, and well-informed. But in doing so, you need to be careful not to lose your own voice. You should never use a wordy, artificial style in an attempt to impress your readers; neither should you talk down to them or apologize for your writing.

Choosing the Proper Pronoun Focus

One important consideration in selecting the appropriate voice for your paper is to choose the proper pronoun focus, and this is dependent upon the nature of the assignment. In some instances, the first person (“I”) is acceptable: for example, if you are writing an autobiographical sketch for an application to a university, anything other than first person would sound odd. Likewise, if you are writing an extemporaneous essay that answers a question prompting a first person response, such as “Explain why you do or do not vote,” again, first person would be the obvious choice. Even within the development of an essay that takes a third person approach, if you use an example from your personal experience to illustrate a point, you can discuss that isolated example using the first person. Most of the same arguments apply to the use of the second person pronoun (“you”). This textbook, for instance, utilizes the second person because of the unique relationship between the student/reader and the instructor/writer.

As discussed in The Use of I in Writing in this book’s section on “Persuasive Essays,” the appropriateness of the first-person pronoun in college writing is a topic of debate. But academic writing more often requires you to adopt a third-person focus, preferably in the plural form (“they”). Using third person enables you to avoid boring the reader by suggesting that the topic is of interest only to you; in other words, it broadens the audience appeal. Using third person in the plural form also allows you to avoid making pronoun agreement errors which might occur as the natural result of imitating spoken English which seems to favor the plural form instead of the more grammatically correct singular: for example, most people would say, “Everyone should have their book in class” instead of “Everyone should have his book in class,” even though the former is technically incorrect. In addition, using third person plural eliminates the problem of sexist language and prevents the awkward use of “his/her.”

Consider the following examples for their use of pronoun focus imagining they appeared in an essay about the validity of using source materials from the Internet:

Examples

Weak Example: As I surfed the Internet, I found a lot of articles that I couldn’t trust because I didn’t see any authors’ names or sponsoring organizations.

Weak Example: As we surf the Internet, we frequently find articles we cannot trust because we do not find authors’ names or sponsoring organizations.

Weak Example: As one surfs the Internet, one frequently finds articles one cannot trust because one cannot find authors’ names or sponsoring organizations.

Stronger Example: Surfing the Internet for source information is unreliable because many articles do not indicate their authors or sponsoring organizations.

The first example is too limited—who cares what you found on the Internet? The second example generalizes the focus better than the first, but it, too, restricts the audience.

Changing the pronoun to “one” is also problematic because it is repetitious and awkward. The final example is the best to use in an essay because it emphasizes the point in an all-inclusive manner, without being redundant or sounding artificial.

EXERCISE 1

Rewrite the following sentences, changing the pronoun focus to best suit an essay written for your ESL Composition class:

- I find that walking is one of the best forms of exercise because it helps me lose weight and improve my cardiovascular system while I can enjoy being outside in the fresh air.

- One should always pay attention to the charges on one’s credit card bills in order to identify if one’s account number has been stolen and to avoid being charged for services one did not receive.

- We believe that we should be able to eat healthy fruits and vegetables without our having to pay exorbitant prices for organically grown food.

- Your best chance of making a lot of money for retirement is to diversify your portfolio, investing in a variety of options instead of putting all of your funds in just one account.

Key Takeaways

- Writing is an effective way to clarify, articulate, and communicate your thoughts.

- Writer’s Block does not have to stall the writing process if you employ effective techniques to overcome it.

- Before you begin to write, adopt a voice and pronoun focus appropriate to your purpose in writing the essay.

Purpose, Audience, Tone, and Content

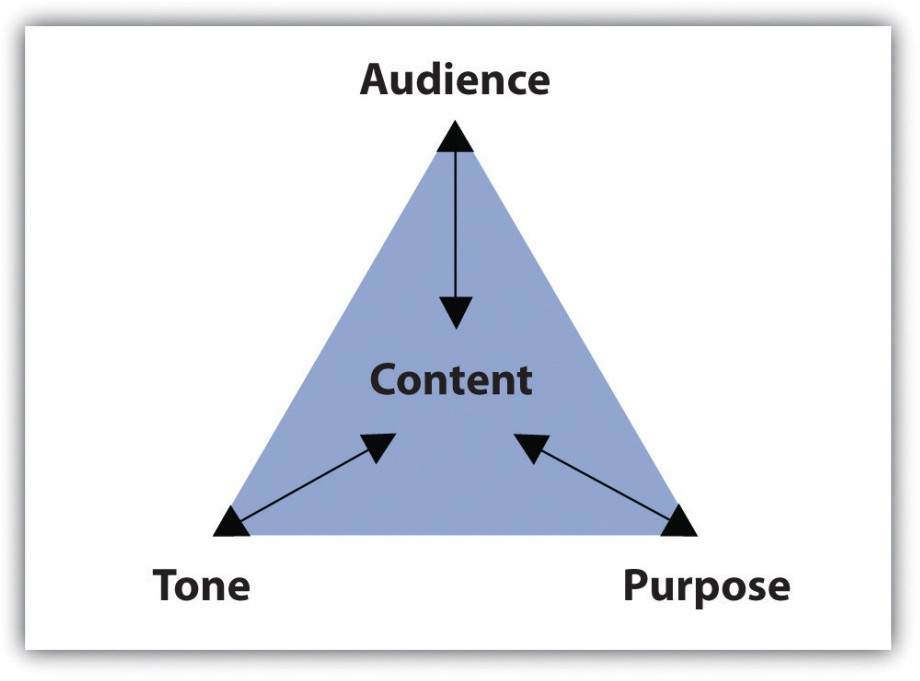

Imagine reading one long block of text, with each idea blurring into the next. Even if you are reading a thrilling novel or an interesting news article, you will likely lose interest in what the author has to say very quickly. During the writing process, it is helpful to position yourself as a reader. Ask yourself whether you can focus easily on each point you make. Keep in mind that three main elements shape the content of each essay:

-

- Purpose: The reason the writer composes the essay.

- Audience: The individual or group whom the writer intends to address.

- Tone: The attitude the writer conveys about the essay’s subject.

The assignment’s purpose, audience, and tone dictate what each paragraph of the essay covers and how the paragraph supports the main point—the thesis.

Identifying Common Academic Purposes

The purpose for a piece of writing identifies the reason you write it by, basically, answering the question “Why?” For example, why write a play? To entertain a packed theater. Why write instructions to the babysitter? To inform him or her of your schedule and rules. Why write a letter to your congressman? To persuade him to address your community’s needs.

In academic settings, the reasons for writing typically fulfill four main purposes:

- to summarize

- to analyze

- to synthesize

- to evaluate

A summary shrinks a large amount of information into only the essentials, using your own words; although shorter than the original piece of writing, a summary should still communicate all the key points and key support of the original document.

An analysis, on the other hand, separates complex materials into their different parts and studies how the parts relate to one another. In the sciences, for example, the analysis of simple table salt would require a deconstruction of its parts—the elements sodium (Na) and chloride (Cl). Then, scientists would study how the two elements interact to create the compound NaCl, or sodium chloride: simple table salt.

In an academic analysis, instead of deconstructing compounds, the essay takes apart a primary source (an essay, a book, an article, etc.) point by point. It communicates the main points of the document by examining individual points and identifying how the points relate to one another.

The third type of writing—synthesis—combines two or more items to create an entirely new item. Take, for example, the electronic musical instrument aptly named the synthesizer. It looks like a simple keyboard but displays a dashboard of switches, buttons, and levers. With the flip of a few switches, a musician may combine the distinct sounds of a piano, a flute, or a guitar—or any other combination of instruments—to create a new sound. The purpose of an academic synthesis is to blend individual documents into a new document by considering the main points from one or more pieces of writing and linking the main points together to create a new point, one not replicated in either document.

Finally, an evaluation judges the value of something and determines its worth. Evaluations in everyday life are often not only dictated by set standards but also influenced by opinion and prior knowledge such as a supervisor’s evaluation of an employee in a particular job. Academic evaluations, likewise, communicate your opinion and its justifications about a particular document or a topic of discussion. They are influenced by your reading of the document as well as your prior knowledge and experience with the topic or issue. Evaluations typically require more critical thinking and a combination of summary, analysis, and synthesis skills.

You will encounter these four purposes not only as you read for your classes but also as you read for work or pleasure, and, because reading and writing work together, your writing skills will improve as you read. Remember that the purpose for writing will guide you through each part of your paper, helping you make decisions about content and style.

When reviewing directions for assignments, look for the verbs that ask you to summarize, analyze, synthesize, or evaluate. Instructors often use these words to clearly indicate the assignment’s purpose. These words will cue you on how to complete the assignment because you will know its exact purpose.

EXERCISE 2

Read the following paragraphs about four films and then identify the purpose of each paragraph: to summarize, to analyze, to synthesize, or to evaluate.

- This film could easily have been cut down to less than two hours. By the final scene, I noticed that most of my fellow moviegoers were snoozing in their seats and were barely paying attention to what was happening on screen. Although the director sticks diligently to the book, he tries too hard to cram in all the action, which is just too ambitious for such a detail-oriented story. If you want my advice, read the book and give the movie a miss.

- During the opening scene, we learn that the character Laura is adopted and that she has spent the past three years desperately trying to track down her real parents. Having exhausted all the usual options—adoption agencies, online searches, family trees, and so on—she is on the verge of giving up when she meets a stranger on a bus. The chance encounter leads to a complicated chain of events that ultimately result in Laura getting her lifelong wish. But is it really what she wants? Throughout the rest of the film, Laura discovers that sometimes the past is best left where it belongs.

- To create the feeling of being gripped in a vice, the director, May Lee, uses a variety of elements to gradually increase the tension. The creepy, haunting melody that subtly enhances the earlier scenes becomes ever more insistent, rising to a disturbing crescendo toward the end of the movie. The desperation of the actors, combined with the claustrophobic atmosphere and tight camera angles create a realistic firestorm, from which there is little hope of escape. Walking out of the theater at the end feels like staggering out of a Roman dungeon.

- The scene in which Campbell and his fellow prisoners assist the guards in shutting down the riot immediately strikes the viewer as unrealistic. Based on the recent reports on prison riots in both Detroit and California, it seems highly unlikely that a posse of hardened criminals will intentionally help their captors at the risk of inciting future revenge from other inmates. Instead, both news reports and psychological studies indicate that prisoners who do not actively participate in a riot will go back to their cells and avoid conflict altogether. Examples of this lack of attention to detail occur throughout the film, making it almost unbearable to watch.

Collaboration: Share with a classmate and compare your answers.

EXERCISE 3

Group Activity: Working in a group of four or five, assign each group member the task of collecting one document each. These documents might include magazine or newspaper articles, workplace documents, academic essays, chapters from a reference book, film or book reviews, or any other type of writing. As a group, read through each document and discuss the author’s purpose for writing. Use the information you have learned in this chapter to decide whether the main purpose is to summarize, analyze, synthesize, or evaluate. Write a brief report on the purpose of each document, using supporting evidence from the text.

EXERCISE 4

Consider the essay most recently assigned to you. Identify the most effective academic purpose for the assignment.

- My assignment: ___________________________

- My purpose: _____________________________

Writing at Work

Thinking about the purpose of writing a report in the workplace can help focus and structure the document. A summary should provide colleagues with a factual overview of your findings without going into too much specific detail. In contrast, an evaluation should include your personal opinion, along with supporting evidence, research, or examples to back it up. To help determine a purpose for writing, listen for words such as summarize, analyze, synthesize, or evaluate when your boss asks you to complete a report.

Identifying the Audience

Imagine you must give a presentation to a group of executives in an office. Weeks before the big day, you spend time creating and rehearsing the presentation. You must make important, careful decisions not only about the content but also about your delivery. Will the presentation require technology to project figures and charts? Should the presentation define important words, or will the executives already know the terms? Should you wear your suit and dress shirt? The answers to these questions will help you develop an appropriate relationship with your audience, making them more receptive to your message.

Now imagine you must explain the same business concepts from your presentation to a group of high school students. Those important questions you previously answered may now require different answers. The figures and charts may be too sophisticated, and the terms will certainly require definitions. You may even reconsider your outfit and sport a more casual look. Because the audience has shifted, your presentation and delivery will shift as well to create a new relationship with the new audience.

In these two situations, the audience—the individuals who will watch and listen to the presentation—plays a role in the development of presentation. As you prepare the presentation, you visualize the audience to anticipate their expectations and reactions. What you imagine affects the information you choose to present and how you will present it. Then, during the presentation, you meet the audience in person and discover immediately how well you perform.

Although the audience for writing assignments—your readers—may not appear in person, they play an equally vital role. Even in everyday writing activities, you identify your readers’ characteristics, interests, and expectations before making decisions about what you write. In fact, thinking about audience has become so common that you may not even detect the audience-driven decisions.

For example, you update your status on a social networking site with the awareness of who will digitally follow the post. If you want to brag about a good grade, you may write the post to please family members. If you want to describe a funny moment, you may write with your friends’ senses of humor in mind. Even at work, you send emails with an awareness of an unintended receiver who could intercept the message.

In other words, being aware of “invisible” readers is a skill you most likely already possess and one you rely on every day. Consider the following paragraphs. Which one would the author send to her parents? Which one would she send to her best friend?

Example A

Last Saturday, I volunteered at a local hospital. The visit was fun and rewarding. I even learned how to do cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or CPR. Unfortunately, I think I caught a cold from one of the patients. This week, I will rest in bed and drink plenty of clear fluids. I hope I am well by next Saturday to volunteer again.

Example B

OMG! You won’t believe this! My advisor forced me to do my community service hours at this hospital all weekend! We learned CPR but we did it on dummies, not even real peeps. And some kid sneezed on me and got me sick! I was so bored and sniffling all weekend; I hope I don’t have to go back next week. I def do NOT want to miss the basketball tournament!

Most likely, you matched each paragraph to its intended audience with little hesitation. Because each paragraph reveals the author’s relationship with the intended readers, you can identify the audience fairly quickly. When writing your own essays, you must engage with your audience to build an appropriate relationship given your subject.

Imagining your readers during each stage of the writing process will help you make decisions about your writing. Ultimately, the people you visualize will affect what and how you write.

While giving a speech, you may articulate an inspiring or critical message, but if you left your hair a mess and laced up mismatched shoes, your audience would not take you seriously. They may be too distracted by your appearance to listen to your words.

Similarly, grammar and sentence structure serve as the appearance of a piece of writing. Polishing your work using correct grammar will impress your readers and allow them to focus on what you have to say.

Because focusing on audience will enhance your writing, your process, and your finished product, you must consider the specific traits of your audience members. Use your imagination to anticipate the readers’ demographics, education, prior knowledge, and expectations.

- Demographics: These measure important data about a group of people, such as their age range, their ethnicity, their religious beliefs, or their gender. Certain topics and assignments will require these kinds of considerations about your audience. For other topics and assignments, these measurements may not influence your writing in the end. Regardless, it is important to consider demographics when you begin to think about your purpose for writing.

- Education: Education considers the audience’s level of schooling. If audience members have earned a doctorate degree, for example, you may need to elevate your style and use more formal language. Or, if audience members are still in college, you could write in a more relaxed style. An audience member’s major or emphasis may also dictate your writing.

- Prior knowledge: This refers to what the audience already knows about your topic. If your readers have studied certain topics, they may already know some terms and concepts related to the topic. You may decide whether to define terms and explain concepts based on your audience’s prior knowledge. Although you cannot peer inside the brains of your readers to discover their knowledge, you can make reasonable assumptions. For instance, a nursing major would presumably know more about health- related topics than a business major would.

- Expectations: These indicate what readers will look for while reading your assignment. Readers may expect consistencies in the assignment’s appearance, such as correct grammar and traditional formatting like double-spaced lines and legible font. Readers may also have content-based expectations given the assignment’s purpose and organization. In an essay titled “The Economics of Enlightenment: The Effects of Rising Tuition,” for example, audience members may expect to read about the economic repercussions of college tuition costs.

EXERCISE 5

On your own sheet of paper, generate a list of characteristics under each category for each audience. This list will help you later when you read about tone and content.

- Your classmates

- Demographics

- Education

- Prior knowledge

- Expectations

- Your instructor

- Demographics

- Education

- Prior knowledge

- Expectations

- The head of your academic department

- Demographics

- Education

- Prior knowledge

- Expectations

- Now think about your next writing assignment. Identify the purpose (you may use the same purpose listed in Exercise 4), and then identify the audience. Create a list of characteristics under each category.

- My assignment:

- My purpose

- My audience:

- Demographics

- Education

- Prior knowledge

- Expectations

Collaboration: Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

EXERCISE 6

At some point during your career, you may be asked to write a report or to complete a presentation. Imagine that you have been asked to report on the issue of health and safety in the workplace. Using the information in this section complete an analysis of your intended audience—your fellow office workers. Consider how demographics, education, prior knowledge, and expectations will influence your report and explain how you will tailor it to your audience accordingly.

Collaboration: Pair with a classmate and compare your answers.

Selecting an Appropriate Tone

Tone identifies a speaker’s attitude toward a subject or another person. You may pick up a person’s tone of voice fairly easily in conversation. A friend who tells you about her weekend may speak excitedly about a fun skiing trip. An instructor who means business may speak in a low, slow voice to emphasize her serious mood. Or, a coworker who needs to let off some steam after a long meeting may crack a sarcastic joke.

Just as speakers transmit emotion through voice, writers can transmit a range of attitudes and emotions through prose–from excited and humorous to somber and critical. These emotions create connections among the audience, the author, and the subject, ultimately building a relationship between the audience and the text. To stimulate these connections, writers intimate their attitudes and feelings with useful devices, such as sentence structure, word choice, punctuation, and formal or informal language. Keep in mind that the writer’s attitude should always appropriately match the audience and the purpose.

Read the following paragraph and consider the writer’s tone. How would you describe the writer’s attitude toward wildlife conservation?

Many species of plants and animals are disappearing right before our eyes. If we don’t act fast, it might be too late to save them. Human activities, including pollution, deforestation, hunting, and overpopulation, are devastating the natural environment. Without our help, many species will not survive long enough for our children to see them in the wild. Take the tiger, for example. Today, tigers occupy just seven percent of their historical range, and many local populations are already extinct. Hunted for their beautiful pelts and other body parts, the tiger population has plummeted from one hundred thousand in 1920 to just a few thousand. Contact your local wildlife conservation society today to find out how you can stop this terrible destruction.

EXERCISE 7

Think about the assignment, purpose, and audience that you selected in previous exercises. Now, identify the tone you would use in the assignment.

- My assignment:

- My purpose:

- My audience:

- My tone:

Choosing Appropriate, Interesting Content

Content refers to all the written substance in a document. After selecting an audience and a purpose, you must choose what information will make it to the page. Content may consist of examples, statistics, facts, anecdotes, testimonies, and observations, but no matter the type, the information must be appropriate and interesting for the audience and purpose. An essay written for third graders that summarizes the legislative process, for example, would have to contain succinct and simple content.

Content is also shaped by tone. When the tone matches the content, the audience will be more engaged, and you will build a stronger relationship with your readers. Consider that audience of third graders. You would choose simple content that the audience will easily understand, and you would express that content through an enthusiastic tone.

The same considerations apply to all audiences and purposes.

EXERCISE 8

Match the content of the following listed examples to the appropriate audience and purpose. On your own sheet of paper, write the correct letter in the blank next to the word “content.”

A. Whereas economist Holmes contends that the financial crisis is far from over, the presidential advisor Jones points out that it is vital to catch the first wave of opportunity to increase market share. We can use elements of both experts’ visions. Let me explain how.

B. In 2000, foreign money flowed into the United States, contributing to easy credit conditions. People bought larger houses than they could afford, eventually defaulting on their loans as interest rates rose.

C. The Emergency Economic Stabilization Act, known by most of us as the humongous government bailout, caused mixed reactions. Although supported by many political leaders, the statute provoked outrage among grassroots groups. In their opinion, the government was actually rewarding banks for their appalling behavior.

Audience: An instructor

Purpose: To analyze the reasons behind the 2007 financial crisis

Content:__________________________________________

Audience: Classmates

Purpose: To summarize the effects of the $700 billion government bailout

Content:__________________________________________

Audience: An employer

Purpose: To synthesize two articles on preparing businesses for economic recovery

Content:__________________________________________

Collaboration: Share with a classmate and compare your answers

EXERCISE 9

Using the assignment, purpose, audience, and tone from Exercise 7, generate a list of content ideas. Remember that content consists of examples, statistics, facts, anecdotes, testimonies, and observations.

- My assignment: __________________________________________

- My purpose: __________________________________________

- My audience: __________________________________________

- My tone: __________________________________________

- My content ideas: __________________________________________

Key Takeaways

- The content of each paragraph in the essay is shaped by purpose, audience, and tone.

- The four common academic purposes are to summarize, to analyze, to synthesize, and to evaluate.

- Identifying the audience’s demographics, education, prior knowledge, and expectations will affect how and what you write.

- Devices such as sentence structure, word choice, punctuation, and formal or informal language communicate tone and create a relationship between the writer and his or her audience.

- Content may consist of examples, statistics, facts, anecdotes, testimonies, and observations. All content must be appropriate and interesting for the audience, purpose and tone.

Methods of Organizing Your Writing

The method of organization for essays and paragraphs is just as important as content. When you begin to draft an essay or paragraph, your ideas may seem to flow from your mind in a seemingly random manner; however, your readers, who bring to the table different backgrounds, viewpoints, and ideas, need you to clearly organize these ideas to help them draw connections between the body and the thesis. A solid organizational pattern not only helps readers to process and accept your ideas, but also gives your ideas a path that you can follow as you develop your essay (or paragraph). Knowing how you will organize your paragraphs allows you to better express and analyze your thoughts. In addition, planning the structure of your essay before you choose supporting evidence helps you conduct more effective and targeted research. This section covers three ways to organize both essays and paragraphs: chronological order, order of importance, and spatial order.

Chronological Order

Chronological arrangement has the following purposes:

- To explain the history of an event or a topic

- To tell a story or relate an experience

- To explain how to do or to make something

- To explain the steps in a process

Chronological order is mostly used in expository writing, which is a form of writing that narrates, describes, informs, or explains a process. When using chronological order, arrange the events in the order that they actually happened, or will happen if you are giving instructions. This method requires you to use words such as first, second, then, after that, later, and finally. These transition words guide you and your reader through the paper as you expand your thesis. For example, if you are writing an essay about the history of the airline industry, you would begin with its conception and detail the essential timeline events up until present day. You would follow the chain of events using words such as first, then, next, and so on.

Keep in mind that chronological order is most appropriate for the following purposes:

- Writing essays containing heavy research

- Writing essays with the aim of listing, explaining, or narrating

- Writing essays that analyze literary works such as poems, plays, or books

When using chronological order, your introduction should indicate the information you will cover and should also establish the relevance of the information. Your body paragraphs should then provide clear divisions or steps in chronology. You can divide your paragraphs by time (such as decades, wars, or other historical events) or by the same structure of the work you are examining (such as a line-by-line explication of a poem).

EXERCISE 10

Choose an accomplishment you have achieved in your life. The important moment could be in sports, schooling, or extracurricular activities. On your own sheet of paper, list the steps you took to reach your goal. Try to be as specific as possible with the steps you took. Pay attention to using transition words to focus your writing.

EXERCISE 11

On a separate sheet of paper, write a paragraph that describes a process you are familiar with and can do well. Assume that your reader is unfamiliar with the procedure. Remember to use the chronological key words, such as first, second, then, and finally.

Order of importance is best used for the following purposes:

- Persuading and convincing

- Ranking items by their importance, benefit, or significance

- Illustrating a situation, problem, or solution

Most essays move from the least to the most important point, and the paragraphs are arranged in an effort to build the essay’s strength. Sometimes, however, it is necessary to begin with the most important supporting point, such as in an essay that contains a thesis that is highly debatable. When writing a persuasive essay, it is best to begin with the most important point because it immediately captivates your readers and compels them to continue reading.

For example, if you were supporting your thesis that homework is detrimental to the education of community college students, you would want to present your most convincing argument first, and then move on to the less important points for your case. During your career, you may be required to work on a team that devises a strategy for a specific goal of your company, such as increasing profits. When planning your strategy you should organize your steps in order of importance. This demonstrates the ability to prioritize and plan. Using the order of importance technique also shows that you can create a resolution with logical steps for accomplishing a common goal.

EXERCISE 12

On a separate sheet of paper, write a paragraph that discusses a passion of yours. Your passion could be music, a particular sport, film-making, and so on. Your paragraph should be built upon the reasons why you feel so strongly. Briefly discuss your reasons in the order of least to greatest importance.

Spatial Order

Spatial order is best used for the following purposes:

- Helping readers visualize something as you want them to see it

- Evoking a scene using the senses (sight, touch, taste, smell, and sound)

- Writing a descriptive essay

Spatial order means that you explain or describe objects as they are arranged around you in your space, for example in a bedroom. As the writer, you create a picture for your readers, and their perspective is the viewpoint from which you describe what is around you. The view must move in an orderly, logical progression, giving the reader clear directional signals to follow from place to place. The key to using this method is to choose a specific starting point and then guide the reader to follow your eye as it moves in an orderly trajectory from your starting point. Pay attention to the following student’s description of her bedroom and how she guides the reader through the viewing process, foot by foot.

Attached to my back bedroom wall is a small wooden rack dangling with red and turquoise necklaces that shimmer as I enter. Just to the right of the rack, billowy white curtains frame a large window with a sill that ends just six inches from the floor. The peace of such an image is a stark contrast to my desk, sitting to the right of the window, layered in textbooks, crumpled papers, coffee cups, and an overflowing ashtray. Turning my head to the right, I see a set of two bare windows that frame the trees outside the glass like a three-dimensional painting. Below the windows is an oak chest from which blankets and scarves are protruding. Against the wall opposite the billowy curtains is an antique dresser, on top of which sits a jewelry box and a few picture frames. A tall mirror attached to the dresser takes up much of the lavender wall.

The paragraph incorporates two objectives covered in this chapter: using an implied topic sentence and applying spatial order. Often in a descriptive essay, the two objectives work together.

The following are possible transition words to include when using spatial order:

- Just to the left or just to the right

- Behind

- Between

- On the left or on the right

- Across from

- A little further down

- To the south, to the east, and so on

- A few yards away

- Turning left or turning right

EXERCISE 13

On a separate sheet of paper, write a paragraph using spatial order that describes your commute to work, school, or another location you visit often.

Collaboration: Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

Key Takeaways

- The way you organize your body paragraphs ensures you and your readers stay focused on and draw connections to your thesis statement.

- A strong organizational pattern allows you to articulate, analyze, and clarify your thoughts.

- Planning the organizational structure for your essay before you begin to search for supporting evidence helps you conduct more effective and directed research.

- Chronological order is most commonly used in expository writing. It is useful for explaining the history of your subject, for telling a story, or for explaining a process.

- Order of importance is most appropriate in a persuasion paper as well as for essays in which you rank things, people, or events by their significance.

- Spatial order describes things as they are arranged in space and is best for helping readers visualize something as you want them to see it; it creates a dominant impression

Writing Paragraphs

Imagine reading one long block of text, with each idea blurring into the next. You are likely to lose interest in a piece of writing that is disorganized and spans many pages without breaks. Paragraphs separate ideas into logical, manageable chunks, each paragraph focusing on only one main idea and presenting coherent sentences to support that one point. Because all the sentences in one paragraph support the same point, a paragraph may stand on its own. For most types of informative or persuasive academic writing, writers find it helpful to think of the paragraph analogous to an essay, as each is controlled by a main idea or point, and that idea is developed by an organized group of more specific ideas. Thus, the thesis of the essay is analogous to the topic sentence of a paragraph, just as the supporting sentences in a paragraph are analogous to the supporting paragraphs in an essay.

In essays, each supporting paragraph adds another related main idea to support the writer’s thesis, or controlling idea. Each related supporting idea is developed with facts, examples, and other details that explain it. By exploring and refining one idea at a time, writers build a strong case for their thesis. Effective paragraphing makes the difference between a satisfying essay that readers can easily process and one that requires readers to mentally organize the piece themselves. Thoughtful organization and development of each body paragraph leads to an effectively focused, developed, and coherent essay.

An effective paragraph contains three main parts:

- a topic sentence

- body, supporting sentences

- a concluding sentence

In informative and persuasive writing, the topic sentence is usually the first sentence or second sentence of a paragraph and expresses its main idea, followed by supporting sentences that help explain, prove, or enhance the topic sentence. In narrative and descriptive paragraphs; however, topic sentences may be implied rather than explicitly stated, with all supporting sentences working to create the main idea. If the paragraph contains a concluding sentence, it is the last sentence in the paragraph and reminds the reader of the main point by restating it in different words. The following figure illustrates the most common paragraph structure for informative and persuasive college essays.

| Topic Sentence (topic + comment/ judgement/interpretation): |

|

|

|

|

| Supporting Sentence 1: |

|

|

|

|

| Supporting Sentence 2: |

|

|

|

|

| Supporting Sentence 3: |

|

|

|

|

| Supporting Sentence 4: |

|

|

|

|

| Supporting Sentence 5 |

|

|

|

|

| Supporting Sentence 6: |

|

|

|

|

| Concluding Sentence (summary of comment/judgement/interpretation): |

|

|

|

|

*Note: The number of supporting sentences varies according to the paragraph’s purpose and the writer’s sentence structure.

Creating Focused Paragraphs with Topic Sentences

The foundation of a paragraph is the topic sentence, which expresses the main idea or point of the paragraph. The topic sentence functions two ways: it clearly refers to and supports the essay’s thesis, and it indicates what will follow in the rest of the paragraph. As the unifying sentence for the paragraph, it is the most general sentence, whereas all supporting sentences provide different types of more specific information, such as facts, details, or examples.

An effective topic sentence has the following characteristics:

- A topic sentence provides an accurate indication of what will follow in the rest of the paragraph.

- Weak example: First, we need a better way to educate students.

- Explanation: The claim is vague because it does not provide enough information about what will follow, and it is too broad to be covered effectively in one paragraph.

- Stronger example: Creating a national set of standards for math and English education will improve student learning in many states.

- Explanation: The sentence replaces the vague phrase “a better way” and leads readers to expect supporting facts and examples as to why standardizing education in these subjects might improve student learning in many states.

- Weak example: First, we need a better way to educate students.

- A good topic sentence is the most general sentence in the paragraph and thus does not include supporting details.

- Weak example: Salaries should be capped in baseball for many reasons, most importantly so we don’t allow the same team to win year after year.

- Explanation: This topic sentence includes a supporting detail that should be included later in the paragraph to back up the main point.

- Stronger example: Introducing a salary cap would improve the game of baseball for many reasons.

- Explanation: This topic sentence omits the additional supporting detail so that it can be expanded upon later in the paragraph, yet the sentence still makes a claim about salary caps – improvement of the game.

- Weak example: Salaries should be capped in baseball for many reasons, most importantly so we don’t allow the same team to win year after year.

- A good topic sentence is clear and easy to follow.

- Weak example: In general, writing an essay, thesis, or other academic or nonacademic document is considerably easier and of much higher quality if you first construct an outline, of which there are many different types.

- Explanation: The confusing sentence structure and unnecessary vocabulary bury the main idea, making it difficult for the reader to follow the topic sentence.

- Stronger example: Most forms of writing can be improved by first creating an outline.

- Explanation: This topic sentence cuts out unnecessary verbiage and simplifies the previous statement, making it easier for the reader to follow. The writer can include examples of what kinds of writing can benefit from outlining in the supporting sentences.

- Weak example: In general, writing an essay, thesis, or other academic or nonacademic document is considerably easier and of much higher quality if you first construct an outline, of which there are many different types.

Location of Topic Sentences

A topic sentence can appear anywhere within a paragraph or can be implied (such as in narrative or descriptive writing). In college-level expository or persuasive writing, placing an explicit topic sentence at the beginning of each paragraph (the first sentence) makes it easier for readers to follow the essay and for writers to stay on topic, but writers should be aware of variations and maintain the flexibility to adapt to different writing projects. The following examples illustrate varying locations for the topic sentence. In each example, the topic sentence is underlined.

Topic Sentence Begins the Paragraph (General to Specific)

After reading the new TV guide this week I wondered why we are still being bombarded with reality shows, a plague that continues to darken our airwaves. Along with the return of viewer favorites, we are to be cursed with yet another mindless creation. Prisoner follows the daily lives of eight suburban housewives who have chosen to be put in jail for the purposes of this fake psychological experiment. A preview for the first episode shows the usual tears and tantrums associated with reality television. I dread to think what producers will come up with next season and hope that other viewers will express their criticism. These producers must stop the constant stream of meaningless shows without plotlines. We’ve had enough reality television to last us a lifetime!

The first sentence tells readers that the paragraph will be about reality television shows, and it expresses the writer’s distaste for these shows through the use of the word bombarded. Each of the following sentences in the paragraph supports the topic sentence by providing further information about a specific reality television show and why the writer finds it unappealing. The final sentence is the concluding sentence. It reiterates the main point that viewers are bored with reality television shows by using different words from the topic sentence.

Paragraphs that begin with the topic sentence move from the general to the specific. They open with a general statement about a subject (reality shows) and then discuss specific examples (the reality show Prisoner). Most academic essays contain the topic sentence at the beginning of the first paragraph.

Topic Sentence Ends the Paragraph (Specific to General)

Last year, a cat traveled 130 miles to reach its family, who had moved to another state and had left their pet behind. Even though it had never been to their new home, the cat was able to track down its former owners. A dog in my neighborhood can predict when its master is about to have a seizure. It makes sure that he does not hurt himself during an epileptic fit. Compared to many animals, our own senses are almost dull.

The last sentence of this paragraph is the topic sentence. It draws on specific examples (a cat that tracked down its owners and a dog that can predict seizures) and then makes a general statement that draws a conclusion from these examples (animals’ senses are better than humans’). In this case, the supporting sentences are placed before the topic sentence and the concluding sentence is the same as the topic sentence. This technique is frequently used in persuasive writing. The writer produces detailed examples as evidence to back up his or her point, preparing the reader to accept the concluding topic sentence as the truth.

When the Topic Sentence Appears in the Middle of the Paragraph

For many years, I suffered from severe anxiety every time I took an exam. Hours before the exam, my heart would begin pounding, my legs would shake, and sometimes I would become physically unable to move. Last year, I was referred to a specialist and finally found a way to control my anxiety—breathing exercises. It seems so simple, but by doing just a few breathing exercises a couple of hours before an exam, I gradually got my anxiety under control. The exercises help slow my heart rate and make me feel less anxious. Better yet, they require no pills, no equipment, and very little time. It’s amazing how just breathing correctly has helped me learn to manage my anxiety symptoms.

In this paragraph, the underlined sentence is the topic sentence. It expresses the main idea—that breathing exercises can help control anxiety. The preceding sentences enable the writer to build up to his main point (breathing exercises can help control anxiety) by using a personal anecdote (how he used to suffer from anxiety). The supporting sentences then expand on how breathing exercises help the writer by providing additional information. The last sentence is the concluding sentence and restates how breathing can help manage anxiety. Placing a topic sentence in the middle of a paragraph is often used in creative writing. If you notice that you have used a topic sentence in the middle of a paragraph in an academic essay, read through the paragraph carefully to make sure that it contains only one major topic.

Implied Topic Sentences

Some well-organized paragraphs do not contain a topic sentence at all, a technique often used in descriptive and narrative writing. Instead of being directly stated, the main idea is implied in the content of the paragraph, as in the following narrative paragraph:

Heaving herself up the stairs, Luella had to pause for breath several times. She let out a wheeze as she sat down heavily in the wooden rocking chair. Tao approached her cautiously, as if she might crumble at the slightest touch. He studied her face, like parchment, stretched across the bones so finely he could almost see right through the skin to the decaying muscle underneath. Luella smiled a toothless grin.

Although no single sentence in this paragraph states the main idea, the entire paragraph focuses on one concept—that Luella is extremely old. The topic sentence is thus implied rather than stated so that all the details in the paragraph can work together to convey the dominant impression of Luella’s age. In a paragraph such as this one, an explicit topic sentence would seem awkward and heavy-handed. Implied topic sentences work well if the writer has a firm idea of what he or she intends to say in the paragraph and sticks to it. However, a paragraph loses its effectiveness if an implied topic sentence is too subtle or the writer loses focus.

EXERCISE 16

In each of the following sentence pairs, choose the more effective topic sentence.

| 1 | a. This paper will discuss the likelihood of the Democrats winning the next election. |

| b. To boost their chances of winning the next election, the Democrats need to listen to public opinion. | |

| 2 | a. The unrealistic demands of union workers are crippling the economy for three main reasons. |

| b. Union workers are crippling the economy because companies are unable to remain competitive as a result of added financial pressure. | |

| 3. | a. Authors are losing money as a result of technological advances. |

| b. The introduction of new technology will devastate the literary world. | |

| 4. | a. Rap music is produced by untalented individuals with oversized egos. |

| b. This essay will consider whether talent is required in the rap music industry. |

EXERCISE 17

Read the following statements and evaluate each as a topic sentence.

- Exercising three times a week is healthy.

- Sexism and racism exist in today’s workplace.

- I think we should raise the legal driving age.

- Owning a business.

- There are too many dogs on the public beach.

EXERCISE 18

Create a topic sentence on each of the following subjects. Write your responses on your own sheet of paper.

- An endangered species

- The cost of fuel

- The legal drinking age

- A controversial film or novel

Developing Paragraphs

If you think of a paragraph as a sandwich, the supporting sentences are the filling between the bread. They make up the body of the paragraph by explaining, proving, or enhancing the controlling idea in the topic sentence. The overall method of development for paragraphs depends upon the essay as a whole and the purpose of each paragraph; thus paragraphs may be developed by using examples, description, narration, comparison and contrast, definition, cause and effect, classification and division. A writer may use one method, or combine several methods

Writers often want to know how many words a paragraph should contain, and the answer is that a paragraph should develop the idea, point, or impression completely enough to satisfy the writer and readers. Depending on their function, paragraphs can vary in length from one or two sentences, to over a page; however, in most college assignments, successfully developed paragraphs usually contain approximately one hundred to two hundred and fifty words and span one-fourth to two-thirds of a typed page. A series of short paragraphs in an academic essay can seem choppy and unfocused, whereas paragraphs that are one page or longer can tire readers. Giving readers a paragraph break on each page helps them maintain focus.

This advice does not mean, of course, that composing a paragraph of a particular number of words or sentences guarantees an effective paragraph. Writers must provide enough supporting sentences within paragraphs to develop the topic sentence and simultaneously carry forward the essay’s main idea.

For example: In a descriptive paragraph about a room in the writer’s childhood home, a length of two or three sentences is unlikely to contain enough details to create a picture of the room in the reader’s mind, and it will not contribute in conveying the meaning of the place. In contrast, a half page paragraph, full of carefully selected vivid, specific details and comparisons, provides a fuller impression and engages the reader’s interest and imagination. In descriptive or narrative paragraphs, supporting sentences present details and actions in vivid, specific language in objective or subjective ways, appealing to the readers’ senses to make them see and experience the subject. In addition, some sentences writers use make comparisons that bring together or substitute the familiar with the unfamiliar, thus enhancing and adding depth to the description of the incident, place, person, or idea.

In a persuasive essay about raising the wage for certified nursing assistants, a paragraph might focus on the expectations and duties of the job, comparing them to that of a registered nurse. Needless to say, a few sentences that simply list the certified nurse’s duties will not give readers a complete enough idea of what these healthcare professionals do. If readers do not have plenty of information about the duties and the writer’s experience in performing them for what she considers inadequate pay, the paragraph fails to do its part in convincing readers that the pay is inadequate and should be increased.

In informative or persuasive writing, a supporting sentence usually offers one of the following:

- Reason: The refusal of the baby boom generation to retire is contributing to the current lack of available jobs.

- Fact: Many families now rely on older relatives to support them financially.

- Statistic: Nearly 10 percent of adults are currently unemployed in the United States.

- Quotation: “We will not allow this situation to continue,” stated Senator Johns.

- Example: Last year, Bill was asked to retire at the age of fifty-five.

The type of supporting sentence you choose will depend on what you are writing and why you are writing. For example, if you are attempting to persuade your audience to take a particular position, you should rely on facts, statistics, and concrete examples, rather than personal opinions. Personal testimony in the form of an extended example can be used in conjunction with the other types of support.

Consider the elements in the following paragraph:

| Topic sentence: |

| There are numerous advantages to owning a hybrid car. |

| Sentence 1 (statistic): |

| First, they get 20 percent to 35 percent more miles to the gallon than a fuel-efficient gas-powered vehicle. |

| Sentence 2 (fact): |

| Second, they produce very few emissions during low speed city driving. |

| Sentence 3 (reason): |

| Because they do not require gas, hybrid cars reduce dependency on fossil fuels, which helps lower prices at the pump. |

| Sentence 4 (example): |

| Alex bought a hybrid car two years ago and has been extremely impressed with its performance. |

| Sentence 5 (quotation): |

| “It’s the cheapest car I’ve ever had,” she said. “The running costs are far lower than previous gas powered vehicles I’ve owned.” |

| Concluding sentence: |

| Given the low running costs and environmental benefits of owning a hybrid car, it is likely that many more people will follow Alex’s example in the near future. |

Sometimes the writing situation does not allow for research to add specific facts or other supporting information, but paragraphs can be developed easily with examples from the writer’s own experience.

Hripsime, a student in an ESL Advanced Composition class, quickly drafted an essay during a timed writing assignment in class. To practice improving paragraph development, she selected the body paragraph below to add support:

Topic: Would you be better off if you didn’t own a television? Discuss.

Original paragraph:

Lack of ownership of a television set is also a way to preserve innocence, and keep the exposure towards anything inappropriate at bay. From simply watching a movie, I have seen things I shouldn’t have, no matter how fast I switch the channel. Television shows not only display physical indecency, but also verbal. Many times movies do voice-overs of profane words, but they also leave a few words uncensored. Seeing how all ages can flip through and see or hear such things make t.v. toxic for the mind, and without it I wouldn’t have to worry about what I may accidentally see or hear.

The original paragraph identifies two categories of indecent material, and there is mention of profanity to provide a clue as to what the student thinks is indecent. However, the paragraph could use some examples to make the idea of inappropriate material clearer. Hripsime considered some of the television shows she had seen and made a few changes.

Revised paragraph:

Not owning a television set would also be a way to preserve innocence and keep my exposure to anything inappropriate at bay. While searching for a program to view, I have seen things I shouldn’t have, no matter how fast I switched the channel. The synopsis of Euro Trip, which describes high school friends traveling across Europe, leads viewers to think that the film is an innocent adventure; however; it is filled with indecency, especially when the students reach Amsterdam. The movie Fast and Furious has the same problem since the women are all half-naked in half tops and mini-skirts or short-shorts. Television shows not only display physical indecency, but also verbal. Many television shows have no filters, and the characters say profane words freely. On Empire, one of the most viewed dramas today, the main characters Cookie and Lucious Lyon use profane words during their fights throughout entire episodes. Because The Big Bang Theory is a show about a group of science geeks and their cute neighbor, viewers might think that these science geniuses’ conversations would be about their current research or other science topics. Instead, their characters regularly engage in conversations about their personal lives that should be kept private. The ease of flipping through channels and seeing or hearing such things makes t.v. toxic for the mind, and without a television I wouldn’t have to worry about what I may accidentally see or hear.

Hripsime’s addition of a few examples helps to convey why she thinks she would be better off without a television.

Consider the paragraph below on the topic of trauma in J. D. Salinger’s work, noticing how examples are used to develop the paragraph.

Thesis:

Author J.D. Salinger relied primarily on his personal life and belief system as the foundation for the themes in the majority of his works.

Supporting Point/Topic Sentence:

Salinger, a World War II veteran, suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder, a disorder that influenced themes in many of his works.

Examples 1 – 3: A title and description of each work are used to establish support for the topic sentence.

Salinger, a World War II veteran, suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder, a disorder that influenced the themes in many of his works. He did not hide his mental anguish over the horrors of war and once told his daughter, “You never really get the smell of burning flesh out of your nose, no matter how long you live.” His short story “A Perfect Day for Bananafish” details a day in the life of a WWII veteran who was recently released form an army hospital for psychiatric problems. The man acts questionably with a little girl he meets on the beach before he returns to his hotel room and commits suicide. Another short Story, “For Esme – with Love and Squalor,” is narrated by a traumatized soldier who sparks an unusual relationship with a young girl he meets before he departs to partake in D-Day. Finally, in Salinger’s only novel, The Catcher in the Rye, he continues with the theme of post-traumatic stress, though not directly related to war. From a rest home for the mentally ill, sixteen-year-old Holden Caulfield narrates the story of his nervous breakdown following the death of his younger brother.

Concluding Sentences

An effective concluding sentence draws together all the ideas raised in your paragraph. It reminds readers of the main point—the topic sentence—without restating it in exactly the same words. Using the hamburger example, the top bun (the topic sentence) and the bottom bun (the concluding sentence) are very similar. They frame the “meat” or body of the paragraph.

Compare the topic sentence and concluding sentence from the first example on hybrid cars:

Topic Sentence:

There are many advantages to owning a hybrid car.

Concluding Sentence:

Given the low running costs and environmental benefits of owning a hybrid car, it is likely that many more people will follow Alex’s example in the near future.

Notice the use of the synonyms advantages and benefits. The concluding sentence reiterates the idea that owning a hybrid is advantageous without using the exact same words. It also summarizes two examples of the advantages covered in the supporting sentences: low running costs and environmental benefits.

Writers should avoid introducing any new ideas into a concluding sentence because a conclusion is intended to provide the reader with a sense of completion. Introducing a subject that is not covered in the paragraph will confuse readers and weaken the writing.

A concluding sentence may do any of the following:

- Restate the main idea.

- Example: Childhood obesity is a growing problem in the United States.

- Summarize the key points in the paragraph.

- Example: A lack of healthy choices, poor parenting, and an addiction to video games are among the many factors contributing to childhood obesity.

- Draw a conclusion based on the information in the paragraph.

- Example: These statistics indicate that unless we take action, childhood obesity rates will continue to rise.

- Make a prediction, suggestion, or recommendation about the information in the paragraph.

- Example: Based on this research, more than 60 percent of children in the United States will be morbidly obese by the year 2030 unless we take evasive action.

- Offer an additional observation about the controlling idea.

- Example: Childhood obesity is an entirely preventable tragedy.

Paragraph Length

Although paragraph length is discussed in the section on developing paragraphs with supporting sentences, some additional reminders about when to start a new paragraph may prove helpful to writers:

- If a paragraph is over a page long, consider providing a paragraph break for readers. Look for a logical place to divide the paragraph; then revise the opening sentence of the second paragraph to maintain coherence.

- A series of short paragraphs can be confusing and choppy. Examine the content of the paragraphs and combine ones with related ideas or develop each one further.

- When dialogue is used, begin a new paragraph each time the speaker changes.

- Begin a new paragraph to indicate a shift in subject, tone, or time and place.

EXERCISE 19

Use one of the topic sentences created in Exercise 18 and develop a paragraph with supporting details

EXERCISE 20

Identify the topic sentence, supporting sentences, and concluding sentence in the following paragraph.

The desert provides a harsh environment in which few mammals are able to adapt. Of these hardy creatures, the kangaroo rat is possibly the most fascinating. Able to live in some of the most arid parts of the southwest, the kangaroo rat neither sweats nor pants to keep cool. Its specialized kidneys enable it to survive on a miniscule amount of water. Unlike other desert creatures, the kangaroo rat does not store water in its body but instead is able to convert the dry seeds it eats into moisture. Its ability to adapt to such a hostile environment makes the kangaroo rat a truly amazing creature.

Collaboration: Pair with another student and compare your answers.

EXERCISE 21

On your own paper, write one example of each type of concluding sentence based on a topic of your choice.

Improving Paragraph Coherence

A strong paragraph holds together well, flowing seamlessly from the topic sentence into the supporting sentences and on to the concluding sentence. To help organize a paragraph and ensure that ideas logically connect to one another, writers use a combination of elements:

- A clear organizational pattern: chronological (for narrative writing and describing processes), spatial (for descriptions of people or places), order of importance, general to specific (deductive), specific to general (inductive)

- Transitional words and phrases: These connecting words describe a relationship between ideas.

- Repetition of ideas: This element helps keep the parts of the paragraph together by maintaining focus on the main idea, so this element reinforces both paragraph coherence and unity.

In the following example, notice the use of transitions (underlined) and key words (red):

Owning a hybrid car benefits both the owner and the environment. First, these cars get 20 percent to 35 percent more miles to the gallon than a fuel-efficient gas-powered vehicle. Second, they produce very few emissions during low speed city driving. Because they do not require gas, hybrid cars reduce dependency on fossil fuels, which helps lower prices at the pump. Alex bought a hybrid car two years ago and has been extremely impressed with its performance. “It’s the cheapest car I’ve ever had,” she said. “The running costs are far lower than previous gas-powered vehicles I’ve owned.” Given the low running costs and environmental benefits of owning a hybrid car, it is likely that many more people will follow Alex’s example in the near future.

Words such as first and second are transition words that show sequence or clarify order. They help organize the writer’s ideas by showing that he or she has another point to make in support of the topic sentence. The transition word because is a transition word of consequence that continues a line of thought. It indicates that the writer will provide an explanation of a result. In this sentence, the writer explains why hybrid cars will reduce dependency on fossil fuels (because they do not require gas).

In addition to transition words, the writer repeats the word hybrid (and other references such as these cars, and they), and ideas related to benefits to keep the paragraph focused on the topic and hold it together.

To include a summarizing transition for the concluding sentence, the writer could rewrite the final sentence as follows:

In conclusion, given the low running costs and environmental benefits of owning a hybrid car, it is likely that many more people will follow Alex’s example in the near future.

Although the phrase “in conclusion” certainly reinforces the idea of summary and closure, it is not necessary in this case and seems redundant, as the sentence without the phrase already repeats and summarizes the benefits presented in the topic sentence and flows smoothly from the preceding quotation. The second half of the sentence, in making a prediction about the future, signals a conclusion, also making the phrase “in conclusion” unnecessary. The original version of the concluding sentence also illustrates how varying sentences openings can improve paragraph coherence. As writers continue to practice and develop their style, they more easily make these decisions between using standard transitional phrases and combining the repetition of key ideas with varied sentence openings.

The following table provides some useful transition words and phrases to connect sentences within paragraphs as well as to connect:

Table of Common Transitional Words and Phrases

| Transitions That Show Sequence or Time | ||

| after | before | later |

| afterward | before long | meanwhile |

| as soon as | finally | next |

| at first | firs, second, third | soon |

| at last | in the first place | then |

| Transitions That Show Position | ||

| above | across | at the bottom |

| at the top | behind | below |

| beside | beyond | inside |

| near | next to | opposite |

| to the left, to the right, to the side | under | where |

| Transitions That Show a Conclusion | ||

| indeed | hence | in conclusion |