4.1: Ancient Rome

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 222917

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

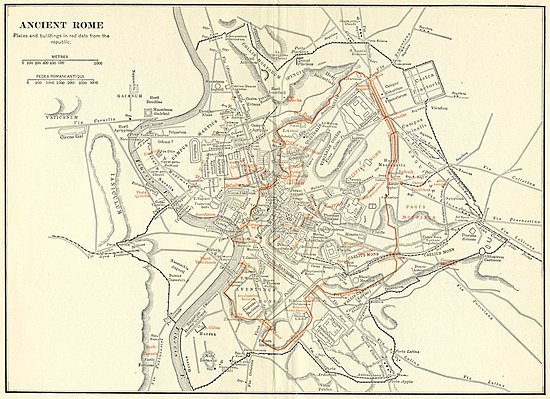

Platner’s map of Rome for The Topography and Monuments of Ancient Rome (1911) from Wikipedia is in the Public Domain.

The Founding of Rome

Myths surrounding the founding of Rome describe the city’s origins through the lens of later figures and events.

The founding of Rome can be investigated through archaeology, but traditional stories, handed down by the ancient Romans themselves, explain the earliest history of their city in terms of legend and myth. The most familiar of these myths, and perhaps the most famous of all Roman myths, is the story of Romulus and Remus, the twins who were suckled by a she-wolf. The twins were abandoned at birth due to a prophecy that they would overthrow the great-uncle who had overthrown their grandfather, which they did when they were grown and understood their origins. After restoring their grandfather to the throne, they established Rome, though in the process Romulus killed his brother.

Romulus and the Founding of Rome

Early Roman Society

Roman society was extremely patriarchal and hierarchical. The adult male head of a household had special legal powers and privileges that gave him jurisdiction over all the members of his family, including his wife, adult sons, adult married daughters, and slaves, but there were multiple, overlapping hierarchies at play within society at large. An individual’s relative position in one hierarchy might have been higher or lower than it was in another. The status of freeborn Romans was established by their ancestry; their census rank, which in turn was determined by the individual’s wealth and political privilege; and citizenship, of which there were grades with varying rights and privileges.

Ancestry

The most important division within Roman society was between patricians, a small elite who monopolized political power, and plebeians, who comprised the majority of Roman society. These designations were established at birth, with patricians tracing their ancestry back to the first Senate established under Romulus. Adult, male non-citizens fell outside the realms of these divisions, but women and children, who were also not considered formal citizens, took the social status of their father or husband. Originally, all public offices were only open to patricians and the classes could not intermarry, but, over time, the differentiation between patrician and plebeian statuses became less pronounced, particularly after the establishment of the Roman republic.

Citizenship

Citizenship in ancient Rome afforded political and legal privileges to free individuals with respect to laws, property, and governance. Most adult, free-born men within the city limits of Rome held Roman citizenship. Free-born women in ancient Rome were considered citizens, but they could not vote or hold political office. The status of woman’s citizenship affected the citizenship of her offspring.

Classes of non-citizens existed and held different legal rights. Under Roman law, slaves were considered property and held no rights. However, certain laws did regulate the institution of slavery, and extended protections to slaves that were not granted to other forms of property.

Ironically, many slaves originated from Rome’s conquest of Greece, and yet Greek culture was considered, in some respects by the Romans, to be superior to their own. In this way, it seems Romans regarded slavery as a circumstance of birth, misfortune, or war, rather than being limited to, or defined by, ethnicity or race.

Skin tones did not carry any social implications, and no social identity, either imposed or assumed, was associated with skin color. Although the color black was associated with ill-omens in the ancient Roman religion, racism as understood today developed only after the classical period:

“The ancients did not fall into the error of biological racism; black skin color was not a sign of inferiority. Greeks and Romans did not establish color as an obstacle to integration in society. An ancient society was one that for all its faults and failures never made color the basis for judging a man.”

— Frank Snowden, Jr.

Women in Wider Society

Roman women had a very limited role in public life. They could not attend, speak in, or vote at political assemblies, and they could not hold any position of political responsibility. Whilst it is true that some women with powerful partners might influence public affairs through their husbands, these were the exceptions. It is also interesting to note that those females who have political power in Roman literature are very often represented as motivated by such negative emotions as spite and jealousy, and, further, their actions are usually used to show their male relations in a bad light. Lower class Roman women did have a public life because they had to work for a living. Typical jobs undertaken by such women were in agriculture, markets, crafts, as midwives and as wet-nurses.

Roman religion was male-dominated, but there were notable exceptions where women took a more public role such as the priestesses of Isis (in the Imperial period) and the Vestals. These latter women, the Vestal Virgins, served for 30 years in the cult of Vesta and they participated in many religious ceremonies, even performing sacrificial rites, a role typically reserved for male priests. There were also several female festivals such as the Bona Dea and some city cults, for example, of Ceres. Women also had a role to play in Judaism and Christianity but, once again, it would be men who debated what that role might entail.

The Establishment of the Roman Republic

In 509, when the Romans overthrew the unpopular king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, and established a republican form of government. The Roman monarchy was overthrown around 509 BCE, during a political revolution that resulted in the expulsion of Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, the last king of Rome. Subsequently, the Roman Republic was established.

Structure of the Republic

The Roman Republic was composed of the Senate, a number of legislative assemblies, and elected magistrates.

The Constitution of the Roman Republic was a set of guidelines and principles passed down, mainly through precedent. The constitution was largely unwritten and uncodified, and evolved over time. Rather than creating a government that was primarily a democracy (as was ancient Athens), an aristocracy (as was ancient Sparta), or a monarchy (as was Rome before, and in many respects after, the Republic), the Roman constitution mixed these three elements of governance into their overall political system. The democratic element took the form of legislative assemblies; the aristocratic element took the form of the Senate; and the monarchical element took the form of the many term-limited consuls.

The Roman Senate

The Senate’s ultimate authority derived from the esteem and prestige of the senators and was based on both precedent and custom. The Senate passed decrees, ostensibly “advice” handed down from the senate to a magistrate. In practice, the magistrates usually followed the senatus consulta. The focus of the Roman Senate was usually foreign policy. However, the power of the Senate expanded over time as the power of the legislative assemblies declined, and eventually the Senate took a greater role in civil law-making.

Legislative Assemblies

Roman citizenship was a vital prerequisite to possessing many important legal rights, such as the rights to trial and appeal, marriage, suffrage, to hold office, to enter binding contracts, and to enjoy special tax exemptions.

Roman Society Under the Republic

In the first few centuries of the Roman Republic, a number of developments affected the relationship between the government and the Roman people, particularly in regard to how that relationship differed across the separate strata of society.

Art and Literature in the Roman Republic

Culture flourished during the Roman Republic with the emergence of great authors, such as Cicero and Lucretius, and with the development of Roman relief and portraiture sculpture.

Roman literature was, from its very inception, heavily influenced by Greek authors. Some of the earliest works we possess are historical epics telling the early military history of Rome, similar to the Greek epic narratives of Homer, Herodotus, and Thucydides. Virgil, though generally considered to be an Augustan poet, and famous for his Aeneid, represents the pinnacle of Roman epic poetry.

The Age of Cicero

Cicero has traditionally been considered the master of Latin prose. The writing he produced from approximately 80 BCE until his death in 43 BCE, exceeds that of any Latin author whose work survives, in terms of quantity and variety of genre and subject matter. His philosophical works were the basis of moral philosophy during the Middle Ages, and his speeches inspired many European political leaders, as well as the founders of the United States.

Crises of the Republic

The 1st century BCE saw tensions between patricians and plebeians erupt into violence, as the Republic became increasingly more divided and unstable.

The Crises of the Roman Republic refers to an extended period of political instability and social unrest that culminated in the demise of the Roman Republic, and the advent of the Roman Empire from about 134 BCE-44 BCE. The exact dates of this period of crisis are unclear or are in dispute from scholar to scholar. Though the causes and attributes of individual crises varied throughout the decades, an underlying theme of conflict between the aristocracy and ordinary citizens drove the majority of actions.

Following a period of great military successes and economic failures of the early Republican period, many plebeian calls for reform among the classes had been quieted. However, many new slaves were being imported from abroad, causing an unemployment crisis among the lower classes. A flood of unemployed citizens entered Rome, giving rise to populist ideas throughout the city.

Julius Caesar

Julius Caesar was a late Republic statesman and general who waged civil war against the Roman Senate, defeating many patrician conservatives before he declared himself dictator.

Gaius Julius Caesar was a Roman general, statesman, consul, and notable author of Latin prose. He played a critical role in the events that led to the demise of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire. Caesar became the first Roman general to cross both when he built a bridge across the Rhine and conducted the first invasion of Britain.

Caesar as Dictator

After assuming control of the government upon the defeat of his enemies in 45 BCE, Caesar began a program of social and governmental reforms that included the creation of the Julian calendar.

To minimize the risk that another general might attempt to challenge him, Caesar passed a law that subjected governors to term limits. All of these changes watered down the power of the Senate, which infuriated those used to aristocratic privilege. Such anger proved to be fuel for Caesar’s eventual assassination.

Despite the defeat of most of his conservative enemies, however, underlying political conflicts had not been resolved. On the Ides of March (March 15) 44 BCE, Caesar was scheduled to appear at a session of the Senate, and a group of senators led by Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus conspired to assassinate him.

Founding of the Roman Empire

Augustus rose to power after Julius Caesar’s assassination, through a series of political and military maneuvers, eventually establishing himself as the first emperor of Rome. He is regarded by many scholars as the founder and first emperor of the Roman Empire. He ruled from 27 BCE until his death in 14 CE.

Augustus was born Gaius Octavius, and in his early years was known as Octavian. He was from an old and wealthy equestrian branch of the plebeian Octavii family. Following the assassination of his maternal great-uncle, Julius Caesar, in 44 BCE, Caesar’s will named Octavian as his adopted son and heir when Octavian was only 19 years old. The young Octavian quickly took advantage of the situation and ingratiated himself with both the Roman people and his adoptive father’s legions, thereby elevating his status and importance within Rome. Octavian found Mark Antony, Julius Caesar’s former colleague and the current consul of Rome, in an uneasy truce with Caesar’s assassins, who had been granted general amnesty for their part in the plot. Nonetheless, Antony eventually succeeded in driving most of them out of Rome, using Caesar’s eulogy as an opportunity to mount public opinion against the assassins.

Mark Antony began amassing political support, and Octavian set about rivaling it. Eventually, many Caesarian sympathizers began to view Octavian as the lesser evil of the two. Octavian allied himself with optimate factions, despite their opposition to Caesar when he was alive.

The Roman Senate, at Octavian’s direction, declared war on Cleopatra’s regime in Egypt and proclaimed Antony a traitor. Antony was defeated by Octavian at the naval Battle of Actium the same year. Defeated, Antony fled with Cleopatra to Alexandria where they both committed suicide. With Antony dead, Octavian was left as the undisputed master of the Roman world. Octavian would assume the title Augustus, and reign as the first Roman Emperor.

The Pax Romana

The Pax Romana, which began under Augustus, was a 200-year period of peace in which Rome experienced minimal expansion by military forces.

Augustus’s Constitutional Reforms

After the demise of the Second Triumvirate, Augustus restored the outward facade of the free Republic with governmental power vested in the Roman Senate, the executive magistrates, and the legislative assemblies. In reality, however, he retained his autocratic power over the Republic as a military dictator. By law, Augustus held powers granted to him for life by the Senate, including supreme military command and those of tribune and censor. It took several years for Augustus to develop the framework within which a formally republican state could be led under his sole rule.

Augustus passed a series of laws between the years 30 and 2 BCE that transformed the constitution of the Roman Republic into the constitution of the Roman Empire. During this time, Augustus reformed the Roman system of taxation, developed networks of roads with an official courier system, established a standing army, established the Praetorian Guard, created official police and fire-fighting services for Rome, and rebuilt much of the city during his reign.

The Julio-Claudian Emperors

The Julio-Claudian emperors expanded the boundaries of the Roman Empire and engaged in ambitious construction projects. However, they were met with mixed public reception due to their unique ruling methods.

Tiberius

Tiberius was the second emperor of the Roman Empire and reigned from 14 to 37 CE. The previous emperor, Augustus, was his stepfather; this officially made him a Julian. However, his biological father was Tiberius Claudius Nero, making him a Claudian by birth. Subsequent emperors would continue the blended dynasty of both families for the next 30 years, leading historians to name it the Julio-Claudian Dynasty. Tiberius is also the grand-uncle of Caligula, his successor, the paternal uncle of Claudius, and the great-grand uncle of Nero.

Tiberius is considered one of Rome’s greatest generals. His conquests laid the foundations for the northern frontier. However, he was known by contemporaries to be dark, reclusive, and somber—a ruler who never really wanted to be emperor. Tiberius attempted to play the part of the reluctant public servant, but came across as derisive and obstructive. His direct orders appeared vague, inspiring more debate than action and leaving the Senate to act on its own.

Caligula

When Tiberius died in 37 CE, his estate and titles were left to Caligula and Tiberius’s grandson, Gemellus, with the intention that they would rule as joint heirs. However, Caligula’s first act as Princeps was to to void Tiberius’s will and have Gemellus executed. When Tiberius died, he had not been well liked. Caligula, on the other hand, was almost universally celebrated when he claimed the title. There are few surviving sources on Caligula’s reign. Caligula’s first acts as emperor were generous in spirit but political in nature. He granted bonuses to the military. He destroyed Tiberius’s treason papers and declared that treason trials would no longer continue as a practice, even going so far as to recall those who had already been sent into exile for treason. He also helped those who had been adversely affected by the imperial tax system, banished certain sexual deviants, and put on large public spectacles, such as gladiatorial games, for the common people.

Although he is described as a noble and moderate ruler during the first six months of his reign, sources portray him as a cruel and sadistic tyrant immediately thereafter. The transitional point seems to center around an illness Caligula experienced in October of 37 CE. It is unclear whether the incident was merely an illness or if Caligula had been poisoned. Either way, following the incident, the young emperor began dealing with what he considered to be serious threats, by killing or exiling those who were close to him. During the remainder of his reign, he worked to increase the personal power of the emperor during his short reign and devoted much of his attention to ambitious construction projects and luxurious dwellings for himself.

In 39 CE, relations between Caligula and the Senate deteriorated. Caligula ordered a new set of treason investigations and trials, replacing the consul and putting a number of senators to death. Many other senators were reportedly treated in a degrading fashion and humiliated by Caligula. In 41 CE, Caligula was assassinated as part of a conspiracy by officers of the Praetorian Guard, senators, and courtiers. The conspirators used the assassination as an opportunity to re-institute the Republic but were ultimately unsuccessful.

Claudius

Claudius, the fourth emperor of the Roman Empire, was the first Roman Emperor to be born outside of Italy. He was afflicted with a limp and slight deafness, which caused his family to ostracize him and exclude him from public office until he shared the consulship with his nephew, Caligula, in 37 CE. Due to Claudius’s afflictions, it is likely he was spared from the many purges of Tiberius and Caligula’s reigns. As a result, Claudius was declared Emperor by the Praetorian Guard after Caligula’s assassination, due to his position as the last man in the Julio-Claudian line.

Despite his lack of experience, Claudius was an able and efficient administrator, as well as an ambitious builder; he constructed many roads, aqueducts, and canals across the Empire. His reign also saw the beginning of the conquest of Britain.

The Last Julio-Claudian Emperors

Nero’s consolidation of personal power led to rebellion, civil war, and a year-long period of upheaval, during which four separate emperors ruled Rome.

Nero

Nero reigned as Roman Emperor from 54 to 68 CE, and was the last emperor in the Julio-Claudian Dynasty. Nero focused on diplomacy, trade, and enhancing the cultural life of the Empire during his rule. He ordered theaters to be built and promoted athletic games.

Nero’s consolidation of power included a slow usurpation of authority from the Senate. Although he had promised the Senate powers equivalent to those it had under republican rule, over the course of the first decade of Nero’s rule, the Senate was divested of all its authority, which led to conspiracies. These conspiracies failed, which led to the execution of all conspirators. Seneca was also ordered to commit suicide after he admitted to having prior knowledge of the plot. Following a rebellion and the refusal of his army officers to follow his commands, Nero committed suicide.

Eruptions of Vesuvius and Pompeii

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE was one of the most catastrophic volcanic eruptions in European history, with several Roman settlements obliterated and buried, and thereby preserved, under ash.

Although his administration was marked by a relative absence of major military or political conflicts, Titus faced a number of major disasters during his brief reign. On August 24, 79 CE, barely two months after the accession of Agricola, Mount Vesuvius erupted, resulting in the almost complete destruction of life and property in the cities and resort communities around the Bay of Naples. The cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum were buried under meters of stone and lava, killing thousands of citizens. Titus appointed two ex-consuls to organize and coordinate the relief effort, while personally donating large amounts of money from the imperial treasury to aid the victims of the volcano. Additionally, he visited Pompeii once after the eruption and again the following year.

The city was lost for nearly 1,700 years before its accidental rediscovery in 1748. Since then, its excavation has provided an extraordinarily detailed insight into the life of a city at the height of the Roman Empire, frozen at the moment it was buried on August 24, 79. The Forum, the baths, many houses, and some out-of-town villas, like the Villa of the Mysteries, remain surprisingly well preserved. On-going excavations reveal new insights into the Roman history and culture.

The Eruption

Reconstructions of the eruption and its effects vary considerably in the details but have the same overall features. The eruption lasted for two days. The morning of the first day, August 24, was perceived as normal by the only eyewitness to leave a surviving document, Pliny the Younger, who at that point was staying on the other side of the Bay of Naples, about 19 miles from the volcano, which may have prevented him from noticing the early signs of the eruption. He was not to have any opportunity, during the next two days, to talk to people who had witnessed the eruption from Pompeii or Herculaneum (indeed he never mentions Pompeii in his letter), so he would not have noticed early, smaller fissures and releases of ash and smoke on the mountain, if such had occurred earlier in the morning.

Around 1:00 p.m., Mount Vesuvius violently exploded, throwing up a high-altitude column from which ash began to fall, blanketing the area. Rescues and escapes occurred during this time. At some time in the night or early the next day, August 25, pyroclastic flows in the close vicinity of the volcano began. Lights seen on the mountain were interpreted as fires. The flows were rapid-moving, dense, and very hot, knocking down wholly or partly all structures in their path, incinerating or suffocating all population remaining there and altering the landscape, including the coastline. These were accompanied by additional light tremors and a mild tsunami in the Bay of Naples. By evening of the second day the eruption was over, leaving only haze in the atmosphere, through which the sun shone weakly.

Pliny the Younger wrote an account of the eruption:

Broad sheets of flame were lighting up many parts of Vesuvius; their light and brightness were the more vivid for the darkness of the night… it was daylight now elsewhere in the world, but there the darkness was darker and thicker than any night.

In Pompeii, the eruption destroyed the city, killing its inhabitants and burying it under tons of ash. Evidence for the destruction originally came from a surviving letter by Pliny the Younger, who saw the eruption from a distance and described the death of his uncle, Pliny the Elder, an admiral of the Roman fleet, who tried to rescue citizens. The site was lost for about 1,500 years until its initial rediscovery in 1599 and broader rediscovery almost 150 years later. The objects that lay beneath the city have been preserved for centuries because of the lack of air and moisture. These artifacts provide an extraordinarily detailed insight into the life of a city during the Pax Romana. During the excavation, plaster was used to fill in the voids in the ash layers that once held human bodies. This allowed archaeologists to see the exact position the person was in when he or she died.

Flavian Architecture

Under the Flavian Dynasty, a massive building program was undertaken, leaving multiple enduring landmarks in the city of Rome, the most spectacular of which was the Flavian Amphitheater, better known as the Colosseum.

The Flavian Dynasty is perhaps best known for its vast construction program on the city of Rome, intended to restore the capital from the damage it had suffered during the Great Fire of 64, and the civil war of 69. Vespasian added the temple of Peace and the temple to the deified Claudius. In 75, a colossal statue of Apollo, begun under Nero as a statue of himself, was finished on Vespasian’s orders, and he also dedicated a stage of the theater of Marcellus. Construction of the Flavian Amphitheater, presently better known as the Colosseum (probably after the nearby statue), was begun in 70 CE under Vespasian, and finally completed in 80 under Titus. In addition to providing spectacular entertainments to the Roman populace, the building was also conceived as a gigantic triumphal monument to commemorate the military achievements of the Flavians during the Jewish wars. Adjacent to the amphitheater, within the precinct of Nero’s Golden House, Titus also ordered the construction of a new public bath-house, which was to bear his name. Construction of this building was hastily finished to coincide with the completion of the Flavian Amphitheater.

The Nerva-Antonine Dynasty

The Nerva-Antonine Dynasty was a dynasty of seven Roman Emperors who ruled over the Roman Empire during a period of prosperity from 96 CE to 192 CE. The most famous of these is Marcus Aurelius.

Hadrian

Hadrian was Roman Emperor from 117 to 138 CE. Known for his grand building projects, he re-built the Pantheon and constructed the Temple of Venus and Roma. He is also known for building Hadrian’s Wall, which marked the northern limit of Roman Britain. Evidence of the wall still exists. During his reign, Hadrian traveled to nearly every province of the Empire. An ardent admirer of Greece, he sought to make Athens the cultural capital of the empire, and created a popular cult in the name of his Greek lover, Antinous. He spent extensive amounts of his time with the military; he usually wore military attire and even dined and slept amongst the soldiers.

Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius was Roman Emperor from 161 to 180 CE. He was the last of the Five Good Emperors and was a practitioner of Stoicism. His untitled writing, commonly known as the Meditations, is the most significant source of our modern understanding of ancient Stoic philosophy.

Constantine and Christianity

The first recorded official persecution of Christians on behalf of the Roman Empire was in AD 64, when, as reported by the Roman historian Tacitus, Emperor Nero attempted to blame Christians for the Great Fire of Rome. According to Church tradition, it was during the reign of Nero that Peter and Paul were martyred in Rome. However, modern historians debate whether the Roman government distinguished between Christians and Jews prior to Nerva’s modification of the Fiscus Judaicus in 96, from which point practising Jews paid the tax and Christians did not.

Christians suffered from sporadic and localized persecutions over a period of two and a half centuries. Their refusal to participate in the imperial cult was considered an act of treason and was thus punishable by execution. The most widespread official persecution was carried out by Diocletian beginning in 303. During the Great Persecution, the emperor ordered Christian buildings and the homes of Christians torn down and their sacred books collected and burned. Christians were arrested, tortured, mutilated, burned, starved, and condemned to gladiatorial contests to amuse spectators. The Great Persecution officially ended in April 311, when Galerius, which granted Christians the right to practice their religion, although it did not restore any property to them. Constantine, caesar in the Western Empire, and Licinius, caesar in the East, also were signatories to the edict.

During Constantine’s reign, (306–337 AD), Christianity began to transition to the dominant religion of the Roman Empire. Historians remain uncertain about Constantine’s reasons for favoring Christianity, and theologians and historians have often argued about which form of early Christianity he subscribed to.

Constantine ruled the Roman Empire as sole emperor for much of his reign. Some scholars allege that his main objective was to gain unanimous approval and submission to his authority from all classes, and therefore he chose Christianity to conduct his political propaganda, believing that it was the most appropriate religion that could fit with the imperial cult. Regardless, under the Constantinian dynasty Christianity expanded throughout the empire, launching the era of the state church of the Roman Empire. His formal conversion in 312 is almost universally acknowledged among historians. According to Hans Pohlsander, professor emeritus of history at the University at Albany, SUNY, Constantine’s conversion was just another instrument of realpolitik in his hands meant to serve his political interest in keeping the empire united under his control:

The prevailing spirit of Constantine’s government was one of conservatism. His conversion to and support of Christianity produced fewer innovations than one might have expected; indeed they served an entirely conservative end, the preservation and continuation of the Empire.

— Hans Pohlsander, The Emperor Constantine

Constantine’s decision to cease the persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire was a turning point for early Christianity, sometimes referred to as the Triumph of the Church, the Peace of the Church or the Constantinian shift. The emperor became a great patron of the Church and set a precedent for the position of the Christian emperor within the Church.

Adapted from “The Roman World” by LibreTexts is licensed CC BY-NC 4.0

Adapted from “The Role of Women in the Roman World” by Libre Texts is licensed CC BY-NC-SA

Adapted from “Black People in Ancient Roman History” by Wikipedia is licensed CC-BY-SA.

Adapted from “Constantine the Great and Christianity” by Wikipedia is licensed CC-BY-SA.