1.1: Introduction

- Page ID

- 97896

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Welcome to Modern World History! This is the textbook for an undergraduate survey course taught at all the universities and most of the colleges in the Minnesota State system. Similar courses are taught at institutions around the United States and the world, so the authors have made the text available as an open educational resource that teachers and learners can read, adapt, and reuse to meet their needs. We’d like to hear from people who have found the text useful, and we’re always open to questions and suggestions.

Readers of this text may have varying levels of familiarity with the events of World History before the modern period we will be covering. Occasionally understanding the text may require a bit of background that will help contextualize the material we are covering. This introduction will cover some of that background.

The Agricultural Revolution

Farming developed in a number of different parts of the ancient world, before the beginning of recorded history. That means it’s very difficult for historians to describe early agricultural societies in as much detail as we’d like. Also, because there are none of the written records historians typically use to understand the past, we rely to a much greater extent on archaeologists, anthropologists, and other specialists for the data that informs our histories. And because the science supporting these fields has advanced rapidly in recent years, our understanding of this prehistoric period has also changed – sometimes abruptly.

Farming was once believed to have developed in the Middle East at sites such as Jericho and Mesopotamia six or seven thousand years ago, where the ancestors of modern Europeans were usually credited with the invention of agriculture. More recently, responding to evidence of prehistoric farming in Africa, India, and China, some scholars suggested agriculture may have developed more or less independently in several regions of the world. But it was difficult to imagine how such parallel development could have occurred, with people in different parts of the world not only making the same basic discoveries but making them pretty much simultaneously. Even more recently, scientists have begun to suspect this confusion may reflect the difficulty of finding archaeological evidence, since plant materials decay in the ground much more quickly than arrowheads and stone spear points. And some have suggested we may have been thinking about agriculture wrong.

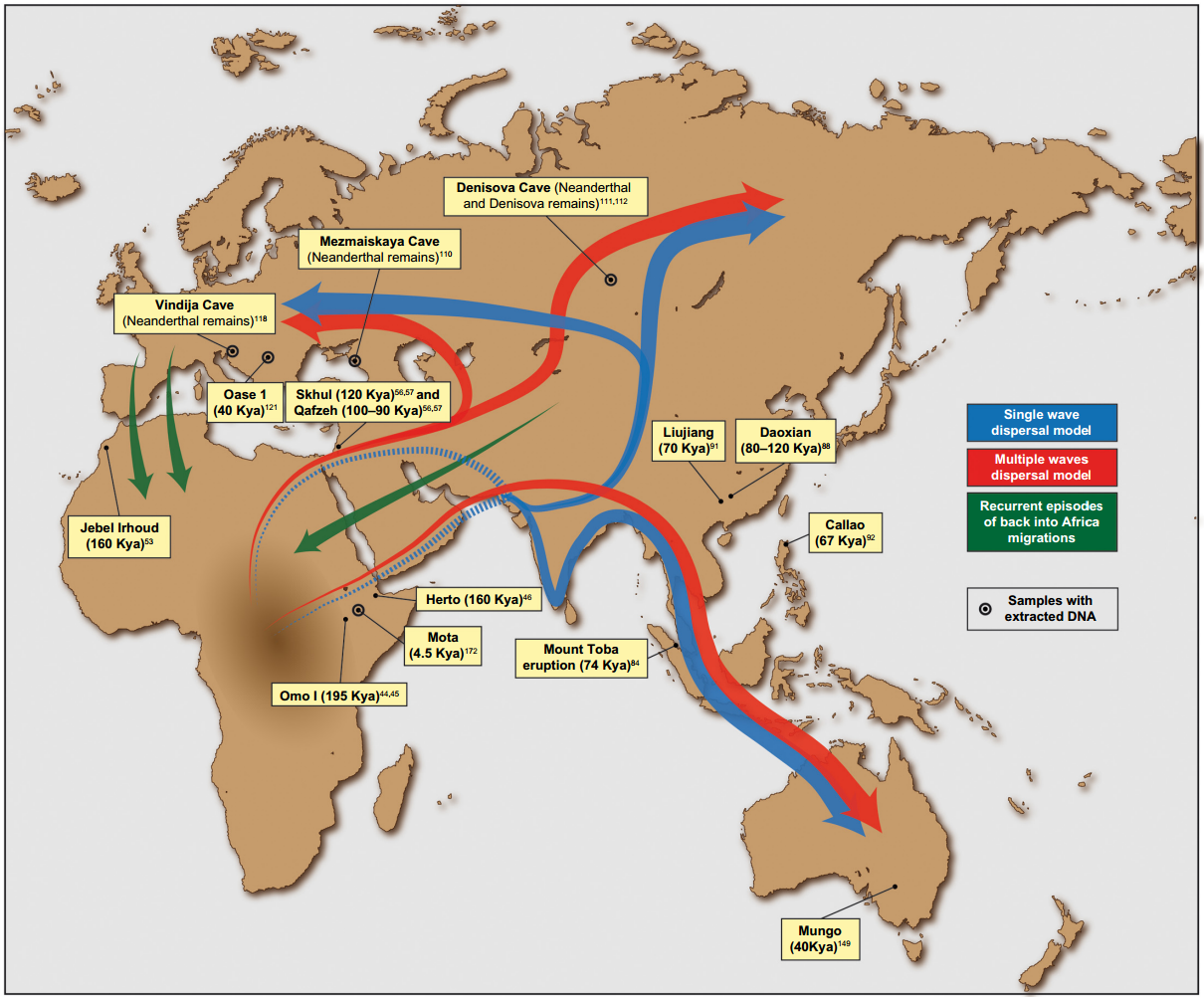

It now seems likely that agriculture began in a very gradual process that goes back much farther than we had imagined. Humans as a species began in southern Africa some 300,000 years ago and after a population crisis about 150,000 years ago, modern humans seem to have left Africa between 80,000 and 100,000 years ago. They were not the first members of the human family that left Africa: Homo erectus, Neanderthals, and Denisovans all lived in Europe and Asia until they were displaced by Homo sapiens.

In the early millennia of their spread across the connected continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia, modern humans lived mobile lives as hunter-gatherers. According to archaeologists, many left traces of their presence in the area north of the Black Sea from about 80,000 to about 50,000 years ago. Although they may have favored certain locations for long periods of time, ancient people were forced to follow the herds they hunted and to seek new food sources when conditions changed. Climate changed very slowly, but the cycle of glaciation was a factor in human development; especially the most recent ice age which began about 36,000 years ago and lasted until about 11,000 years ago. This ice age displaced both animal and human populations, and also allowed some people to migrate to the Americas, as we will see.

Agriculture probably began when hunter-gatherers began favoring certain plants and weeding around them to help them grow larger and make them easier to reach. At some point, people discovered that seeds dropped into rubbish heaps sprouted into new plants. People probably began planting or transplanting their favorites closer to home, so they would not always have to go far, looking for food. This horticulture or part-time farming may have begun before these ancient humans began to spread from the Black Sea area westward into Europe and east into Asia, which would explain the seemingly coincidental parallel development of farming across much of the globe. Various regions may have each developed their distinctive versions of what we now recognize as agriculture from a deep pool of common techniques.

Wheat was discovered in a region we call the fertile crescent, stretching from the Persian Gulf to the eastern Mediterranean. As cultivation spread and surpluses of grain were produced, civilizations like those of Egypt and Mesopotamia (today’s Iraq) rose between 6,000 and 5,000 years ago. About the same time (possibly a bit earlier) residents of the Pearl River estuary in what is now China began cultivating rice in flooded fields called paddies. The three other staple crops of the modern world (corn, potatoes, and cassava) were developed between 9,000 and 7,000 years ago by natives of the Americas, as we will discuss below.

The transition from nomadic hunt-and-gather groups to more complex societies based on agriculture (and the specialization and segmentation of work) allowed for the development of sedentary cultures which established governments, writing and number systems, and hierarchal social systems able to build impressive structures, defend (and sometimes expand) their borders, and create art and music. Let’s look briefly at the ancient societies of Africa, Europe, Asia, and the Americas to prepare for our coverage of them in the early modern period in the opening chapters.

here

- Is it significant that historians must rely on information from other fields like archaeology to tell the story of the ancient world?

- Why does it matter where agriculture first developed?

- Does considering human migrations in the deep past affect your opinions on race and ethnicity?

Ancient Kingdoms of North Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean

The ancient dynasties of the Egyptian empire developed along the Nile beginning around 3100 BCE, built on the wheat surpluses made possible by the annual flooding of the Nile River. Among the most visible and lasting achievements of the Egyptian empires are the pyramids of Giza, built between 2600-2400 BCE to serve as burial tombs for several emperors. The Egyptian empires lasted for nearly 2300 years before being conquered, in succession, by the Assyrians, Persians, and Greeks between about 700 BCE and 332 BCE.

The societies of ancient Greece, particularly in Athens, directly influenced culture and intellectual life in Europe and the Middle East to the present day. Greek dramas and tragedies continue to be studied and performed; Pythagoras’ mathematical discoveries are still taught in schools; and the thinking of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle are the basis for Western philosophy and political science today. The words “democracy” and “republic” come from these ancient Greeks. Greek ideas and culture were adopted by the Romans and spread throughout their empire—indeed, many Greek gods became Roman gods under different names.

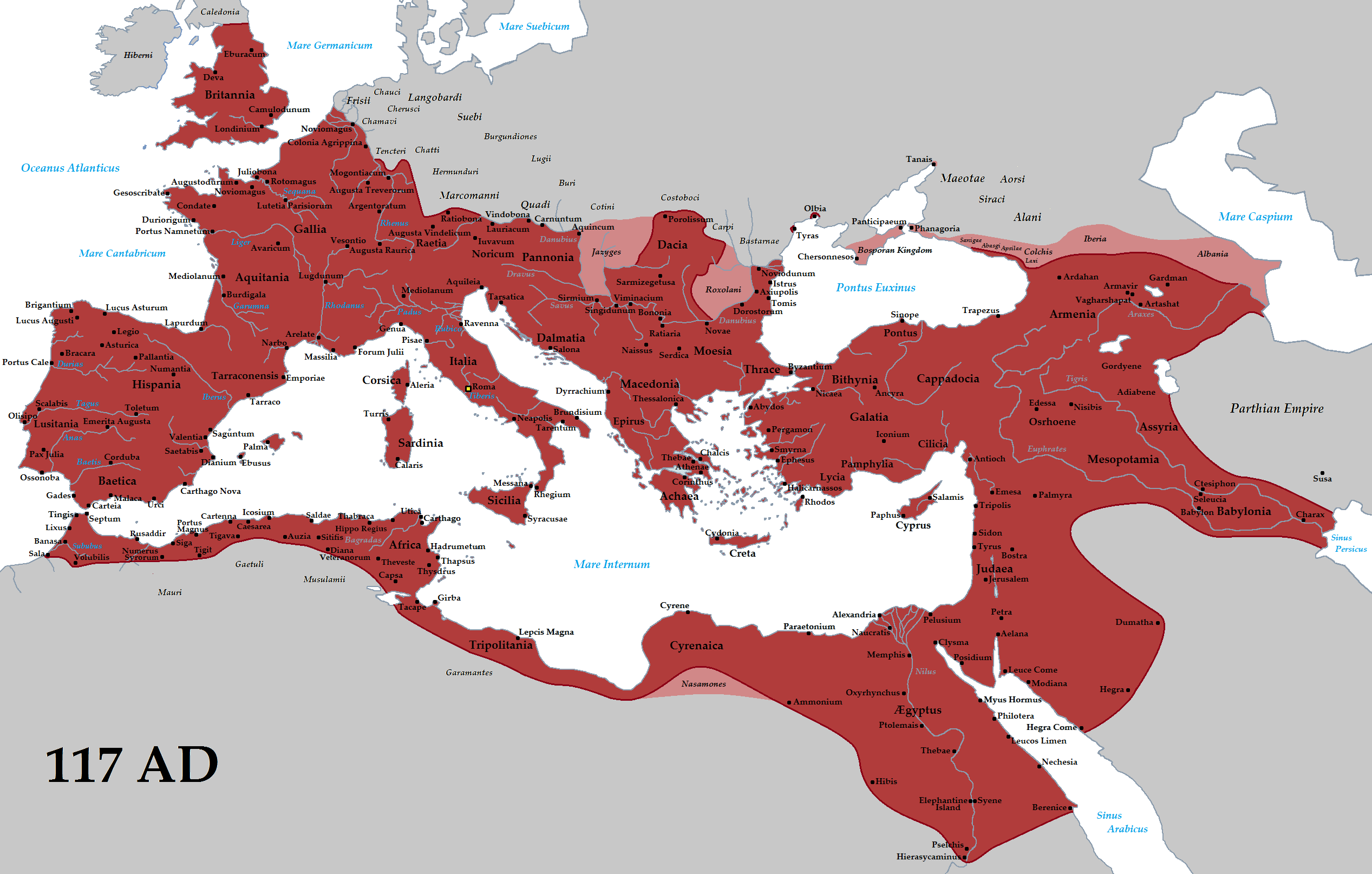

Ancient Rome was a republic for nearly 500 years, expanding its territory from the city of Rome on the western coast of the Italian peninsula to nearly all lands surrounding the Mediterranean Sea, including the former Greek and Egyptian empires and even England. The Romans spread their language (Latin) and their Latin alphabet to western Europe in particular. After a period of political crisis, the Republic was replaced with an Emperor under Caesar Augustus in 27 BCE.

The Egyptian, Greek, Assyrian, Persian, and Roman empires all encountered the Hebrew people, who maintained their own independent kingdom of Israel around 1000 BCE. The Hebrew prophet Moses, influenced by spiritual ideas from the various societies, developed the concept of only one god for his people. Moses’ monotheism was an unusual innovation in an era when most societies worshipped several gods and many honored the gods of other cultures. The Ten Commandments and the laws and regulations attributed to Moses in the Torah not only formed the basis of Judaism, but also Christianity and later Islam—all religions which only worship a single god.

Shortly after the Romans conquered the region of Israel, Jesus of Nazareth, a Jewish thinker, began preaching a new more peaceful and inclusive religion of salvation. He was turned over by enemies to the Romans, who crucified him in approximately 33 CE. His followers, led especially by Paul (said to have never met Jesus), preached that Jesus was the Son of God and invited Gentiles (people who were not Jews) to join the faith. The new religion was especially embraced by slaves in the Roman Empire who were attracted to the promise of forgiveness, of a single, all-powerful God’s unending love, and of eternal life after death. The Romans, who saw the new religion as a challenge to state religious authority, sometimes persecuted Christians.

In 330 CE, the Roman Emperor Constantine banned persecution of Christians, and by 400 AC, Christianity had replaced the worship of Rome’s traditional gods and goddesses as the state religion of the Roman Empire. Because Constantine embraced the new faith, the Roman Catholic Church is the most direct descendent of the Roman Empire. The Pope, leader of the Catholic Church, still lives in Rome, and the vestments of Catholic priests (and the clergy of some other liturgical Christian denominations) are similar to those worn by fourth-century Roman officials.

here

- On what types of historical evidence do you think references to people such as Moses, Jesus, and Muhammad are based? How might these sources differ from the archaeological sources mentioned previously?

- How do the cultures of ancient Europe continue to influence life in the modern world?

The Eastern Roman Empire and the Fall of Rome

Constantine moved the capital of the Roman Empire to a second imperial capital in 330 CE. Byzantium, which he renamed Constantinople, was a powerful fortress controlling the Bosphorus Strait which connects the Black Sea to the Mediterranean. The city of Byzantium, already a thousand years old when Constantine moved there, served as the eastern administrative center of the empire and continued using Greek, rather than Latin, as its official language. A somewhat separate Christian church developed in this Greek part of the empire, based on the idea that the different archbishops controlled spiritual matters as a group, and that the Pope in Rome was only another archbishop, equal to the others. After 1000 CE, Catholics in the west and the Greek Orthodox in the east split from one another.

During the fifth century CE, Germanic tribes from northern Europe invaded the Roman Empire. They, in turn, were fleeing from Attila the Hun and other invaders from Asia. Eventually, the city of Rome itself fell to the barbarians in 476 CE. Western Europe was divided up among various Germanic warlords. But although the empire had ended the Roman Catholic Church remained strong. Over the next 500 years, Christianity spread throughout the region and was embraced by local and regional rulers. The Church preserved much of the culture of the Roman Empire, including its language, Latin, which was used in liturgies and ceremonies until 1965.

Germanic languages were transformed through their contact with Latin speakers. The English language is a good example of both Germanic and Latin influences. Consider how time is measured: the months of the year are all from the Roman calendar, with the first six months named after Roman gods, and July and August named after the early emperors Julius Caesar and Caesar Augustus. The remaining months are ordinal numbers seven through ten—although in a confusing change, the Catholic Church decided to begin the calendar in January, making “December” the twelfth month instead of the tenth. The days of the week, however, reveal both Latin and Germanic influences: Saturday, Sunday, and Monday come from the sacred Roman orbs in the sky—Spanish, French and other more Latin languages continue in this vein for the other four days, but not English, which honors the barbarian gods Tieu, Woden, Thor, and Frija for the remainder of the week.

The Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantium) lasted for nearly another 1000 years after the fall of Rome. You can tell which European peoples were converted by Catholic missionaries and which were proselytized by Orthodox preachers by looking at their alphabets—Russia, the Ukraine, and Bulgaria, for example, use the Greek-based “Cyrillic” alphabet, while all western European languages use a version of the Latin alphabet.

Islam and Its Influence

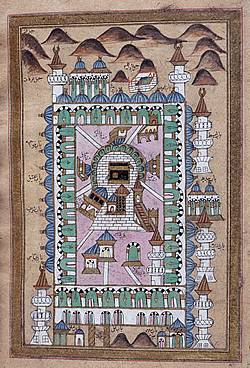

In 610 CE, the Prophet Muhammad began preaching and organizing a new religion—Islam—on the Arabian Peninsula in the region of Mecca. The Prophet’s teachings, later gathered in the Holy Quran, built upon Judaism and Christianity. Mecca itself was long a site of religious pilgrimage honoring the Hebrew patriarch Abraham, and Jesus is considered as an important prophet in Islam. By the time of Muhammad’s passing in 632, Islam was well-established in the eastern Arabian Peninsula; within the next one hundred years, it became the dominant religion in North Africa, the Middle East, and Persia. By 1200, Muslim rulers also dominated South Asia and the Iberian Peninsula.

Islam brought stability to the region and trade, learning, and the exchange of ideas flourished. The extent of Muslim trade is notable in the establishment of a center of Islamic study in Timbuktu in the middle of northern Sub-Saharan Africa, located across the Sahara Desert from Mecca in today’s Mali. Religious conversion often accompanied Arab merchant activity. Indeed, the nation with the largest Muslim population in the world, Indonesia, is a South East Asian archipelago located thousands of miles from the Arabian Peninsula; Arab traders first introduced their religion there in the 1200s. The Arab world benefitted from relatively stable administrations and commercial links that allowed merchants to bring new technology, science, and mathematics from India and China to the region, which Arab scholars refined in their own centers of learning.

Muslims, like Christians, Jews, and followers of all other world religions, may share common sacred writings and liturgical traditions, but are also divided by different theological interpretations and religious practices. In Islam, a principal division stems from an early debate over who should have led the religion after the Prophet: should it have been a member of his family, or simply anyone who was an effective and dynamic leader? Sunnis, 90% of Muslims today, stem from the group who believed in the latter, while Shi’ites, some 10% of all Muslims, include the (often martyred) descendants of the Prophet as early principle imams (spiritual leaders) of Islam. As will be discussed later, the rulers of Persia—today’s Iran—embraced Shi’ism, while most of their neighbors are Sunni. Although Sunnis and Shi’ites fought one another in the early years of Islam, many have also lived together in relative peace for centuries, until the last few decades (which will be examined in later chapters).

here

- How do you think the memory of the Roman Empire affected Europeans?

- How did conflict between Muslims and Christians shape European history?

The Center of World Population: Asia

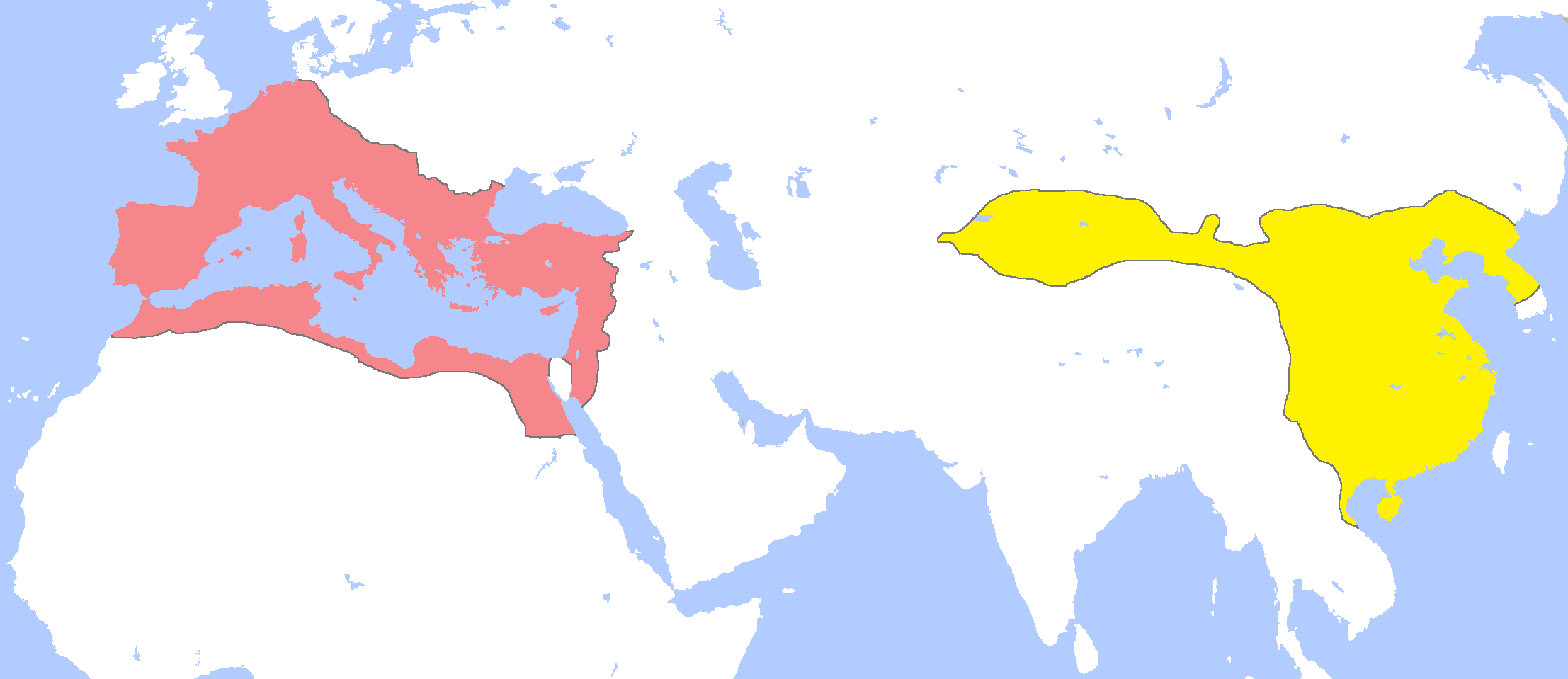

After thousands of years of hunting and gathering, the ancient people of northern China began cultivating millet and rice at about the same time and in much the same way that people of the Middle East grew wheat and people of the Americas grew maize, potatoes, and cassava. China’s recorded history began about 2000 BCE, or over four thousand years ago, so historians have a pretty good idea what happened there in the distant past. Based on irrigated rice agriculture, the population of China grew to 50 to 60 million people as early as 2,000 years ago. This population was originally divided into several small kingdoms whose ruling families were connected through political marriages. Beginning in 221 BCE, the most influential and powerful family organized the kingdoms into an empire covering much of the territory of modern China. This empire lasted over two thousand years under a series of over a dozen dynasties until the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911 and the establishment of the Republic of China.

In the region that is now Pakistan and India, Indus Valley cities such as Mohenjo-daro and Harappa, which reached their maturity by about 2600 BCE, each housed 30,000 to 60,000 people. These cultures grew on an agricultural base focused on wheat, barley, and millet. The permanent nature of sedentary agricultural societies led thinkers to consider in more complex ways how people should live correctly in the world, which led to the establishment of both religious and civil structures that are the ancestors and sources of many of the world governments and religions which still exist today. During the Vedic period in India, Hinduism took root beginning around 2000 BCE, based on stories of gods and goddesses, and their relationships with one another and the world. The spiritual richness of South Asia inspired the Buddha (who was originally from today’s Nepal) to engage in his own spiritual journey to enlightenment in the fifth century BCE. Buddhist ideas inspired the spiritual aspects of Chinese, Japanese, and Southeast Asian thought.

The earliest emperors of China began large public works programs including construction of what they called Long Walls which later formed the basis of the Great Wall, partly to protect from northern tribes and partly to expand their territory northward. Around 200 BCE, the second Chinese dynasty, the Han, established a trade route called the Silk Road linking China through central Asia with Europe. Artifacts from the Roman Empire have been found in China and silk (which China developed before 3000 BCE) became a luxury fabric in Greece and Rome. The next dynasty, the Sui, dug the Grand Canal to connect the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers in the sixth century CE. The canal allowed rice, wheat, and millet to be transported on a protected inland waterway instead of being shipped on the ocean where shipments could be threatened by pirates. China also led the world in iron, copper, and porcelain production as well as in the “Four Great Inventions”: the compass, gunpowder, paper-making, and printing.

here

- Is it significant that China and India have always been centers of world population?

- Why do agricultural surpluses encourage the building of cities, kingdoms, and empires?

- Is it surprising to you that the Han and Roman Empires existed at the same time and that there was trade between Asia and Europe via the Silk Road?

The Isolated Americas

The people living in the Americas were separated by climate change from Eurasia for nearly 12,000 years after the end of the ice age that had created Beringia between what is now Alaska and Siberia, and allowed Eurasians to cross over into the Americas. During this period, which we should remember is twice as long as recorded history, the Native Americans were not idle. When they had arrived in the Americas, they found very few large animal species available to domesticate. Like the Europeans, Asians, and Africans, Native Americans experienced their own agricultural revolution after a long period of hunting and gathering; but instead of domesticating cattle, horses, sheep, goats, pigs, and chickens, Americans developed certain plants, creating three of the world’s current top five staple crops.

Staple crops produce the foods that provide the greatest percentage of the calories people eat. It might surprise you that today only about fifteen staple crops account for 90% of the calories people eat every day. The top five are responsible for nearly three quarters, including feed for the animals whose meat we eat. They were all discovered/invented by ancient people between six and ten thousand years ago, and three of the five were invented in the Americas. The world’s five top five staples today (in order of importance) are maize (corn), rice, wheat, potatoes, and cassava. Only rice and wheat were known to Europe, Asia, and Africa before contact with the Americas. Natives of what is now Mexico developed maize from a native grass called teosinte beginning about nine thousand years ago, and its use spread to nearly every part of the Americas. Over generations, women (who were the farmers in ancient Mexico) selectively bred the grass to produce more and bigger seeds. Maize is currently the most important staple in the world for both human and animal feed, as well as in industrial uses like High Fructose Corn Syrup, plastics and fuel.

Andean natives in what is now Peru and Bolivia created many varieties of potatoes beginning 10,000 years ago. Andean women developed different varieties for different growing conditions and learned to freeze dry potatoes for long-term storage. And the people of the Amazon region not only discovered manioc trees growing in the rainforest, but developed processes to turn the trees’ poisonous roots into cassava (what we know as tapioca) between 10,000 and 7,000 years ago. Raw cassava root is toxic. So in addition to domesticating the plant, Amazonian tree farmers had to develop technologies (combinations of boiling, drying, and chemical leaching) to remove the cyanide compounds and make the manioc useful. Along with rice and wheat developed in Eurasia, maize, potatoes, and manioc are the most important staple crops in the modern world, feeding billions of people. We have ancient native Americans to thank for them.

Of course, eating nothing but maize, potatoes, and cassava would be a very bland diet. The indigenous in central Mexico developed other plants to flavor their cuisine: the various types of hot peppers, beans, and tomatoes present in Mexican food today were enjoyed by the Olmecs, Toltecs, and Mexica hundreds of years before their encounter with Europeans in the sixteenth century. The Meso-Americans also ground cocoa beans and added hot water, peppers, and honey to make hot chocolate–even today, millions of Latin Americans begin and end their day with a cup, prepared in a traditional olleta with a hand-held batidor, using chunks of chocolate. However, such a delicious drink was originally reserved for the nobility, and cocoa beans themselves were often used as a kind of currency.

here

- Why would it matter that there were no large animal species in the Americas for natives to domesticate?

- Is it significant that the people breeding new staple crops in the Americas were mostly women?

We will look more closely in the next several chapters at the cultures of all these regions, as they entered the modern era. Although the people of each continent and region developed different traditions and customs, their agriculturally-based cultures shared a lot of similarities and their civilizations were all comparably advanced at the beginning of our survey. with that introduction, let’s begin.

Media Attributions

- Molino_neolítico_de_vaivén © José-Manuel Benito Álvarez is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Putative_migration_waves_out_of_Africa © Saioa López, Lucy van Dorp and Garrett Hellenthal is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Pyramids_of_the_Giza_Necropolis © KennyOMG is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Roman_Empire_Trajan_117AD © Tataryn is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Europe_and_the_Near_East_at_476_AD © Guriezous is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- OldmapofMecca © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- RomanandHanEmpiresAD1 © Gabagool is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Maize-teosinte © John Doebley is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Manihot_esculenta_dsc07325 © David Monniaux is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license